Vitalik: Encapsulated Complexity vs. Systemic Complexity in Protocol Design

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik: Encapsulated Complexity vs. Systemic Complexity in Protocol Design

Moderately support encapsulating complexity, exercising our judgment in specific situations.

Author: Vitalik Buterin, Co-founder of Ethereum

Translation: Nanfeng, Unitimes

One of the main goals in designing the Ethereum protocol is minimizing complexity: making the protocol as simple as possible while still enabling the blockchain to perform everything a functional blockchain network needs to do. The Ethereum protocol is far from perfect in this regard—especially because many parts were designed in 2014–16, when our understanding was much more limited—but we are still actively and diligently working to reduce complexity wherever possible.

However, one challenge with this goal is that complexity is hard to define. Sometimes, you must weigh trade-offs between two options that introduce different kinds of complexity and carry different costs. How do we compare them?

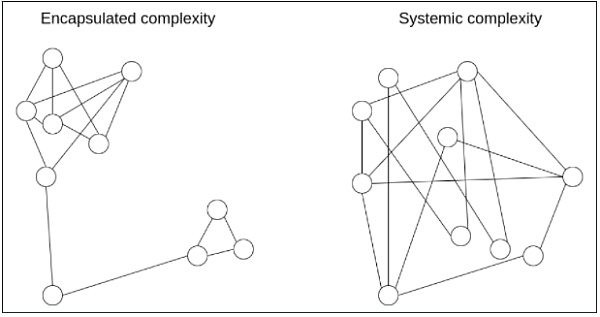

A powerful intellectual tool that enables us to think more precisely about complexity is distinguishing between what we call encapsulated complexity and systemic complexity.

Encapsulated complexity occurs when a subsystem is internally complex but presents a simple "interface" to the outside world. Systemic complexity arises when different parts of a system cannot even be cleanly separated and interact with each other in complicated ways.

Here are several examples.

BLS Signatures vs. Schnorr Signatures

BLS signatures and Schnorr signatures are two commonly used cryptographic signature schemes that can be constructed using elliptic curves.

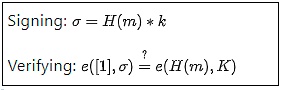

Mathematically, BLS signatures appear very simple:

H is a hash function, m is the message, and k and K are the private and public keys. So far, so good. However, the real complexity is hidden in the definition of the e function: elliptic curve pairings, one of the most difficult-to-understand mathematical concepts in all of cryptography.

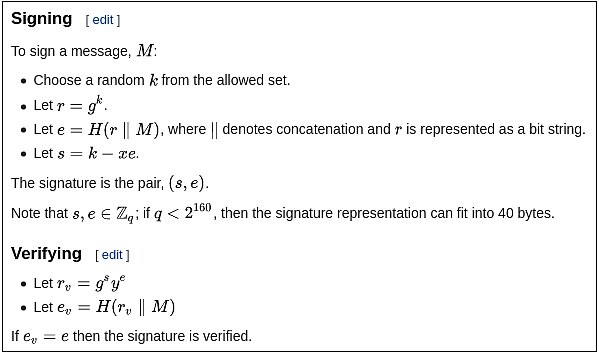

Now consider Schnorr signatures. Schnorr signatures rely only on basic elliptic curves. But the signing and verification logic is slightly more complex:

So… which type of signature is “simpler”? It depends on what you care about! BLS signatures have significant technical complexity, but it is all hidden within the definition of the e function. If you treat the e function as a black box, BLS signatures are actually very simple. On the other hand, Schnorr signatures have lower overall complexity, but involve more components that interact with the external world in subtle ways.

For example:

-

Creating a BLS multisignature (combining two keys k1 and k2) is straightforward: just σ₁+σ₂. But Schnorr multisignatures require two rounds of interaction and are vulnerable to tricky Key Cancellation attacks.

-

Schnorr signatures require randomness generation; BLS signatures do not.

Elliptic curve pairings often act as a powerful "complexity sponge," because they contain large amounts of encapsulated complexity but enable solutions with less systemic complexity. This also applies in the field of polynomial commitments: compare the simplicity of KZG commitments (which require pairings) with the more intricate internal logic of inner product arguments (which do not require pairings).

Cryptography vs. Cryptoeconomics

An important design choice that arises in many blockchain designs is the trade-off between cryptography and cryptoeconomics. Often (e.g., in rollups), this means choosing between validity proofs (i.e., ZK-SNARKs) and fraud proofs.

ZK-SNARKs are technically complex. While the basic idea behind how ZK-SNARKs work can be explained in one article, actually implementing a ZK-SNARK to verify some computation involves many times more complexity than the computation itself (which is why ZK-SNARKs for the EVM are still under development, whereas fraud proofs for the EVM are already in testing). Efficiently implementing a ZK-SNARK proof requires circuit design optimized for specific purposes, unfamiliar programming languages, and numerous other challenges. In contrast, fraud proofs are conceptually simple: if someone raises a challenge, you simply re-execute the computation on-chain. For efficiency, a binary search scheme may sometimes be added, but even then, the added complexity is minimal.

Although ZK-SNARKs are complex, their complexity is encapsulated. On the other hand, the relatively low complexity of fraud proofs is systemic. Here are some examples of systemic complexity introduced by fraud proofs:

-

They require careful incentive engineering to avoid the verifier’s dilemma.

-

If implemented within consensus, they require additional transaction types for fraud proofs, plus mechanisms to handle cases where multiple participants race to submit fraud proofs simultaneously.

-

They depend on a synchronous network.

-

They allow censorship attacks to be weaponized for theft.

-

Rollups based on fraud proofs require liquidity providers to support instant withdrawals.

For these reasons, even from a complexity standpoint, purely cryptographic solutions based on ZK-SNARKs may be more secure in the long run: ZK-SNARKs have more complex components, which some people must account for when adopting them; but ZK-SNARKs have fewer dangling caveats, which everyone must worry about.

Various Examples

-

PoW (Nakamoto Consensus): Low encapsulated complexity, as the mechanism is very simple and easy to understand, but higher systemic complexity (e.g., selfish mining attacks).

-

Hash Functions: High encapsulated complexity, but exhibit very understandable properties, hence low systemic complexity.

-

Random shuffling algorithms: Shuffling algorithms can either be internally complex (e.g., Whisk), ensuring strong randomness and being easy to reason about, or internally simple but producing weaker, harder-to-analyze randomness properties (i.e., higher systemic complexity).

-

Miner Extractable Value (MEV): A protocol powerful enough to support complex transactions may be internally quite simple, but those complex transactions might create intricate systemic effects on the protocol's incentives by leading to highly atypical block proposals.

-

Verkle Trees: Verkle trees do have some encapsulated complexity and are in fact significantly more complex than ordinary Merkle hash trees. However, from a systemic perspective, Verkle trees provide a clean and simple interface equivalent to a key-value map. The main systemic "leak" is the possibility of an attacker manipulating the Verkle tree so that a particular value has an extremely long branch; however, this risk is similar for both Verkle and Merkle trees.

How Do We Weigh These Trade-Offs?

Often, the option with lower encapsulated complexity is also the one with lower systemic complexity, making the simpler choice obvious. But sometimes, you must make difficult decisions between one kind of complexity and another. By now, it should be clear that encapsulated complexity is less dangerous. The risks from systemic complexity are not merely a function of specification length; a small 10-line code snippet in a spec that interacts with other parts can be far more complex than a 100-line function treated as a black box.

However, this preference for encapsulated complexity has its limits. Software bugs can occur in any piece of code, and as code grows larger, the probability of errors approaches 1. Sometimes, when you need to interact with a subsystem in unexpected new ways, what initially seemed like encapsulated complexity becomes systemic.

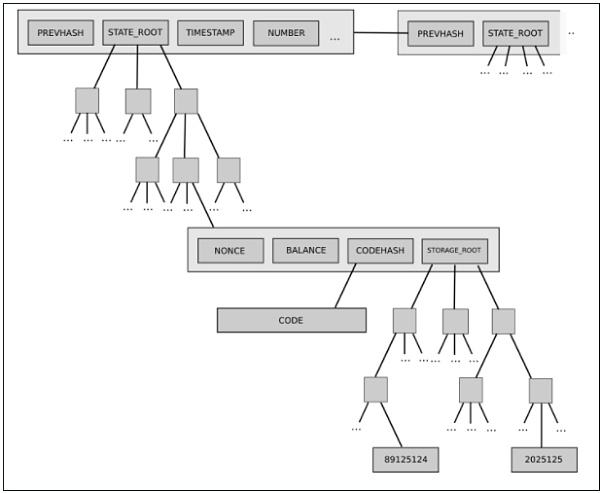

A prime example is Ethereum’s current two-level state tree structure, consisting of a tree of account objects, where each account object in turn has its own storage tree.

This tree structure is complex, but initially, the complexity appeared well encapsulated: the rest of the protocol interacted with the tree as a key/value store for reading and writing, so we didn’t need to worry about how the tree was structured.

However, later on, this complexity proved to have systemic consequences: the ability of accounts to have arbitrarily large storage trees meant there was no reliable way to expect any particular portion of the state (e.g., “all accounts starting with 0x1234”) to have a predictable size. This made state partitioning more difficult and complicated the design of synchronization protocols and efforts to distribute storage processes. Why did encapsulated complexity become systemic? Because the interface changed. What’s the solution? Current proposals to transition to Verkle trees also include moving toward a balanced single-layer tree design.

Ultimately, in any given case, which type of complexity is preferable has no simple answer. The best we can do is moderately favor encapsulated complexity—but not too much—and exercise judgment carefully in each individual situation. Sometimes, sacrificing a bit of systemic complexity to greatly reduce encapsulated complexity is indeed the best approach. Other times, you might even misjudge what is encapsulated and what is not. Every case is different.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News