Andre Cronje: The 2022 Crypto Winter, Currency Collapses, and Regulatory Shortcomings

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Andre Cronje: The 2022 Crypto Winter, Currency Collapses, and Regulatory Shortcomings

Cryptocurrency crash and internet disaster.

Written by: Megan Dyamond

Translated by: Mr. Xizao, MarsBit

1. Introduction

The cryptocurrency market experienced massive shocks in 2022, with multiple cryptocurrencies losing value and numerous networks and exchanges failing, resulting in a total loss of two trillion dollars.

To date, some of the biggest market shocks include the collapse of Terra LUNA/UST, Celsius Network filing for bankruptcy, Voyager Digital filing for bankruptcy, and the downfall of Three Arrows Capital. These events were not isolated—they had significant ripple effects across the entire market, contributing to declines in Bitcoin and Ethereum prices. The most serious consequence has been users’ crypto assets being locked in exchange accounts or held and managed by third parties.

Investors who suffered losses during this "crypto winter" are uncertain about what remedies they can pursue and whether they can claim compensation from irresponsible actors within the system.

Available remedies under current regulations are ineffective. Most investors sign away their rights to their cryptocurrencies through extensive terms and conditions on crypto exchanges, meaning that if an exchange is liquidated, many will be (at best) unsecured creditors.

Crypto exchanges and investment service providers operate much like banks, but without the safeguards and regulatory oversight required of traditional banks. The causes behind recent collapses are neither unique nor new—similar irresponsible practices were evident during the 2008 crash in traditional financial markets.

These behaviors—and their impact on the market—are also nothing new, especially in a market that relies more than any other on consumer expectations. Many regulators suggest that protecting consumers in the crypto market requires adopting relatively established safeguards from traditional finance: setting minimum reserve requirements for exchanges, mandating licensing for service providers, regulating exposure limits, establishing transparency standards, and classifying cryptocurrencies as financial products.

This brings us to the first and perhaps most important event—the recent collapse of Terra USD and Luna. Once praised for offering cutting-edge blockchain investments to global users, Terra is now blamed as the catalyst for the 2022 crypto winter. What went wrong, and why, remains a critical question the market continues to grapple with—alongside regulators.

2. Terra Luna/Terra USD (The Collapse of a Cryptocurrency)

2.1. The Collapse

Terra USD (UST) was a so-called stablecoin launched by Terraform Labs. It used an algorithmic mechanism to maintain its peg to the US dollar, relying on another Terraform cryptocurrency, LUNA, to stabilize its value. The system operated via an arbitrage network where trading between LUNA and UST would correct price deviations—when profitable, traders would sell one token and buy the other, increasing demand for the cheaper asset and pushing its price back up. For a long time, this mechanism worked effectively, keeping UST close to a 1:1 parity with the US dollar. This process also involved burning tokens during trades, which played a role in accelerating the collapse.

A key component of Terra’s ecosystem and stability mechanism was Anchor Protocol, which functioned similarly to a savings account, attracting large deposits of UST in exchange for consistently high yields. At its peak, Anchor held nearly 75% of all circulating UST—making UST's value highly dependent on the continued operation of this pool.

Anchor borrowed UST from lenders and lent it out to borrowers, delivering approximately 20% annual yield to depositors—a function very similar to banking. Starting in March, this yield became unstable, fluctuating with Anchor’s reserves (capital set aside by Terra to sustain the yield). As more lenders joined, attracted by high returns, reserves began depleting to meet payout obligations. A temporary fix involved injecting additional UST into Anchor to boost reserves. Clearly, this wasn’t sustainable, as Anchor lacked sufficient appeal to attract ongoing inflows.

In May 2022, $2 billion worth of UST was withdrawn and liquidated from Anchor Protocol. This placed immense pressure on LUNA, as arbitrageurs exploited growing price discrepancies between LUNA and UST—discrepancies that should never have widened so dramatically. The Luna Foundation attempted to stabilize the peg by injecting more UST into the system (remember, minting LUNA burns UST), trying to regain control over both cryptocurrencies’ prices.

As vast amounts of LUNA flooded the market, it could no longer maintain its value and plummeted. The Luna Foundation’s efforts to use its Bitcoin reserves to stabilize UST/LUNA also failed, flooding the market with large volumes of Bitcoin—causing oversupply and further driving down Bitcoin’s price.

2.2. What Went Wrong?

A series of issues led to Terra’s collapse: insufficient reserves, flawed algorithms, and Anchor Protocol lacking withdrawal limits.

Had there been mechanisms to manage large withdrawals, perhaps UST wouldn’t have de-pegged.

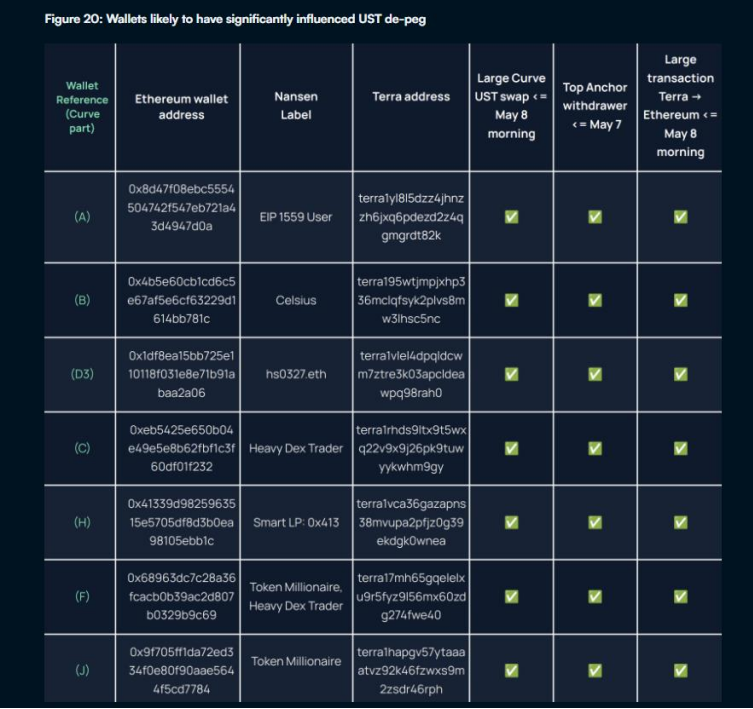

In May 2022, Jump Crypto analyzed UST/LUNA activity and found that only a few large transactions destabilized and ultimately collapsed the currency. These transactions were traced back to a small number of wallets, whose owners remain unidentified. It is alarming that a handful of individuals could destabilize an entire cryptocurrency ecosystem without facing consequences or accountability. This point will be discussed further below.

For a more comprehensive analysis of what went wrong with Terra, refer to Nansen’s report: https://www.nansen.ai/research/on-chain-forensics-demystifying-terrausd-de-peg.

2.3. Withdrawals from Anchor Protocol

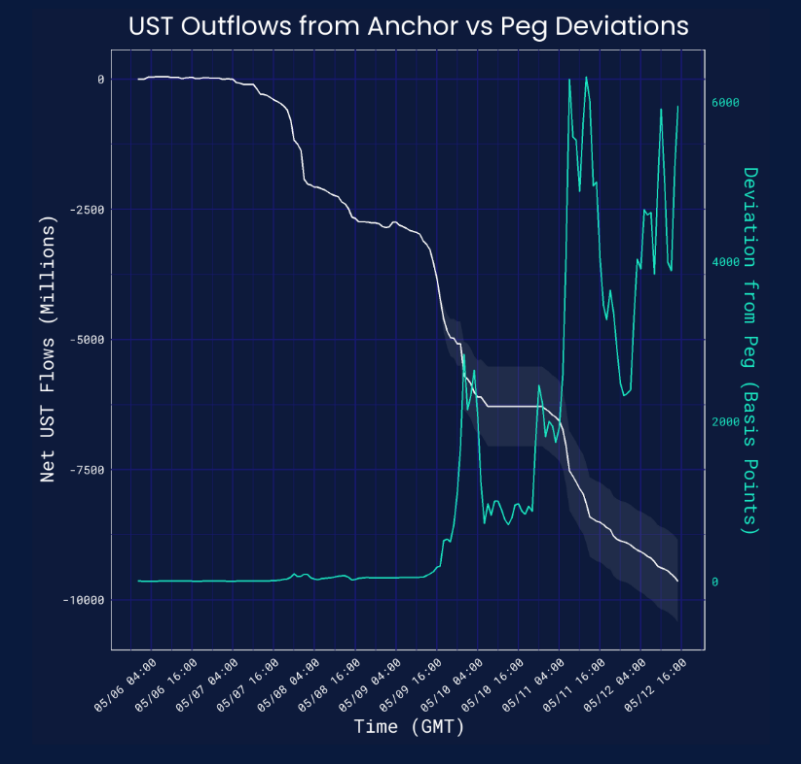

$2 billion in UST withdrawals from Anchor Protocol have been traced to seven wallets, including Celsius Network.

The chart below illustrates how UST deviated further from its dollar peg as funds were pulled from Anchor.

During Nansen’s investigation into UST’s de-pegging, seven influential wallets emerged (see chart below). One wallet has already been identified as belonging to Celsius, whose withdrawal from Anchor caused more harm than benefit. This will be elaborated upon in the next section.

The actions of several major UST holders were enough to destabilize Terra’s ecosystem and cause losses for smaller wallet holders, who now have little recourse for recovery.

Alarmingly, as we will see, Terra’s collapse directly triggered the downfall of several crypto hedge funds and networks. These funds and networks held excessive positions in “stablecoins” (algorithmic stablecoins), and such high-risk investment behavior resulted in losses affecting millions of users’ funds.

Nonetheless, while Terra’s collapse had wide-reaching effects, responsibility cannot rest solely on Terra; the lack of due diligence among large lenders and investors in the crypto market must also bear appropriate blame.

3. Celsius Network (The Collapse of a Cryptocurrency Exchange)

Celsius Network, a prominent cryptocurrency trading platform, filed for bankruptcy in the United States. On June 12, Celsius froze investor accounts and, after a month of uncertainty, announced bankruptcy almost without warning due to severe liquidity issues.

The exact reasons why Celsius could not meet investor withdrawal requests remain unclear. Likely factors include excessive leverage (and inadequate reserves), poor decision-making by executives, and potential misconduct by key stakeholders and senior management at Celsius.

3.1. ETH and STETH

To understand the recent collapse of Celsius and its associated token CEL, here is a brief explanation of Celsius’s staking operations.

Celsius heavily invested in stETH, a token representing ETH (Ethereum network tokens) staked on Ethereum 2.0’s Beacon Chain—an upgraded version of the Ethereum blockchain using a different validation method. stETH aims to earn rewards during Ethereum’s transition ("upgrade"). The Ethereum Merge shifts the current network from proof-of-work consensus to proof-of-stake. Essentially, stETH represents ETH locked in decentralized smart contracts, earning rewards for long-term investors. To earn these rewards, users stake their stETH into liquidity pools across various networks, which keep stETH’s price aligned with ETH, allowing them to benefit from ETH’s future value on the new network.

Celsius users handed over control of their ETH private keys to Celsius, which then staked those tokens into stETH via smart contracts. When Celsius needed to withdraw ETH, it sold stETH on the Curve liquidity pool in exchange for ETH. Excessive trading and redemption of stETH for ETH disrupted the 1:1 price peg—increased demand drove up ETH’s price. As the Curve pool drained, Celsius lacked sufficient ETH to meet customer withdrawal demands. The initial de-pegging of stETH mirrored Terra’s collapse, as users feared instability and sought to return to the main network. According to Nansen, a second wave intensified the de-peg as other major players tried to offload their stETH holdings.

This triggered a bank run on Celsius, with panicked users rushing to withdraw investments, ultimately forcing Celsius to freeze its network. The ensuing liquidity crisis led Celsius to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on July 17, 2022.

3.2. Anchor Protocol

Celsius had substantial user funds invested in Terra’s Anchor Protocol. Although it withdrew most of its funds before Terra’s collapse, this action proved to be a double-edged sword. The withdrawal added pressure to UST’s de-peg, causing panic among consumers about crypto market instability—leading to widespread crypto withdrawals and price drops.

It also impacted other currencies held by Celsius, particularly Bitcoin, which was directly affected by Terra’s attempts to stabilize UST (causing Bitcoin’s price to fall).

3.3. Bad Loans

In its bankruptcy filing, Celsius classified 30% of its user loans as non-performing—approximately $310 million. These are loans issued by Celsius that borrowers failed to repay and were essentially written off on Celsius’s books.

Celsius further disclosed that Three Arrows Capital owed it nearly $40 million in debt—repayment of which is unlikely given 3AC’s own bankruptcy.

Overall, the exchange reported a deficit of nearly $1.2 billion on its balance sheet—the CEO, Mashinsky, attributed this to “bad investments.”

3.4. Alleged Misconduct and Lack of Regulation

Since freezing investor accounts in June 2022, multiple lawsuits have been filed against Celsius Network, some alleging clear fraud.

Certain actions taken prior to the account freeze remain unexplained by Celsius—for example, a $320 million payment to FTX exchange and Celsius’s highly leveraged positions. The payment to FTX occurred shortly before customer accounts were frozen and was reportedly made to repay a loan. Under normal insolvency proceedings, such payments may be considered preferential treatment to creditors when a company is nearing bankruptcy. Courts often order such payments reversed so that creditors are treated fairly according to their priority—even if the recipient did nothing wrong.

The statistics above represent the final weekly data released by Celsius before freezing customer accounts on June 12. The week of May 6–12 showed massive outflows and negative holding returns.

Celsius essentially operated like a bank, yet lacked the institutional framework supporting traditional banking. Accepting customer assets (cryptocurrencies) closely resembles accepting deposits in traditional finance—a tightly regulated activity. Further lending out these deposits by staking them in liquidity pools mirrors how banks use customer deposits, yet without the insurance protections offered in traditional finance.

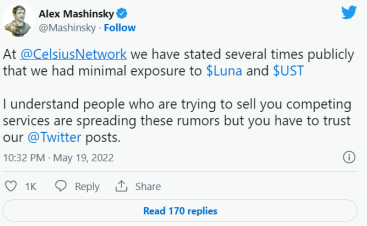

Prior to its collapse, CEO Alex Mashinsky’s tweets appear to have deliberately misled the public—at the very least violating his fiduciary duties to Celsius. Some claims state that Mashinsky explicitly told the public that Celsius had minimal exposure to UST—when in fact, it was one of the largest wallets contributing to UST’s de-peg.

In fact, until June 12, Celsius was actively attracting new customers, launching promotional products designed to draw in liquidity and offering incentives to users who committed to six-month lock-up periods.

Mashinsky’s tweet on June 12 was in response to user inquiries about withdrawals. Allegedly, the withdrawal function had been non-functional for several days before accounts were officially frozen.

Given that cryptocurrencies are not regulated like financial products or fiat currencies, it cannot be said that Celsius violated specific regulations. However, it could be deemed negligent—failing to exercise prudence and/or intentionally misleading consumers.

Regardless, now that Celsius has filed for bankruptcy, consumers are left wondering what remedies remain—unfortunately, the answer is very few.

3.5. Consumer Rights in Bankruptcy

In July 2022, Celsius filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the United States. This allows a company to restructure its debts while continuing operations.

Generally, Chapter 11 prioritizes repayment to secured creditors first, followed by unsecured creditors, and finally equity holders. Most Celsius account holders are unsecured creditors, meaning they will only be repaid after secured creditors (typically those with the largest outstanding debts) are paid, and only proportionally based on remaining available assets in Celsius’s accounts.

This is because when fiat or cryptocurrency is deposited into Celsius, it becomes part of a pooled fund combined with other users’ deposits (“commixtio”). Therefore, users do not have a right to reclaim specific fiat or crypto assets, but only to recover the value they contributed, subject to the terms agreed upon with Celsius, as detailed in the terms and conditions. Protections and ownership rights related to deposits under standard banking law do not apply to crypto exchanges, and exchange agreements can exempt them from liability in cases of total deposit loss.

The risk of complete loss of deposits in Celsius is disclosed and disclaimed in its terms:

"By lending qualifying digital assets to Celsius or otherwise using the services, you will not have any right to profits or income generated by Celsius from any subsequent use (or otherwise) of any digital asset, nor will you bear any losses Celsius may suffer as a result. However, you will bear the risk that Celsius may be unable to repay all or part of its obligations, in which case your digital assets may be at risk."

Notably, depositing fiat currency is treated no differently than depositing digital assets. Normally, when lending assets, the owner retains ownership and has the right to demand return of the specific asset. That is not the case here—depositors relinquish ownership of their crypto assets and hold only unsecured claims to the value they contributed.

"Subject to applicable laws, during the period you choose to use qualifying digital assets in the Earn Service (if you are eligible), thereby lending those qualifying digital assets to us through your Celsius account, or using them as collateral in the Borrow Service (if you are eligible), you grant Celsius all rights and interests in those qualifying digital assets, including ownership, and the right to hold the digital asset in Celsius's own virtual wallets or elsewhere, without further notice to you, and to pledge, re-pledge, triple-pledge, multi-pledge, sell, lend, or otherwise transfer or use the digital asset, alone or together with other property, along with all accompanying ownership rights, throughout any period of ownership."

When regulating the crypto industry, exchanges should be the first point of control for regulators. While we champion the decentralization of DeFi, these exchanges are in fact centralized—as central access points to the crypto market. Investors placing “deposits” on crypto exchanges have no legal rights to those funds, unlike in traditional finance where deposits receive special legal protection. Traditional finance also offers depositors a certain level of transparency, which crypto exchanges lack. This transfer of control over crypto assets away from investors, coupled with a lack of transparency, completely distorts the purpose of blockchain and decentralized finance, leaving investors questioning why they chose decentralization over traditional finance in the first place. I will discuss potential regulations below—ones that, if properly implemented, could not only protect the industry but also promote its growth.

4. Three Arrows Capital (Cryptocurrency Hedge Fund)

In mid-2022, the collapse of Three Arrows Capital (3AC) shocked many in the industry. Founded in 2012 and investing in crypto assets since 2017, 3AC primarily focused on crypto derivatives but also invested in companies developing crypto products and technologies. At its peak, 3AC managed around $10 billion in assets.

3AC’s downfall was tied to its exposure to Terra. It had purchased 10.9 million LUNA tokens for $500 million and staked them. As Terra collapsed, the value of 3AC’s holdings dropped sharply—those LUNA tokens are now worth only $670.

3AC also held large positions in Grayscale’s Bitcoin Trust (GBTC), which had been trading at a discount since the rise of crypto ETFs. After Terra’s crash, 3AC’s main strategy centered on GBTC arbitrage, betting that GBTC would eventually convert to an ETF, reversing the discount. This didn’t happen. Meanwhile, Bitcoin’s price fell as Terra sold its Bitcoin reserves, further eroding the value of 3AC’s other holdings. 3AC also used GBTC shares to borrow stablecoins, reinvesting in Terra to repay Bitcoin loans. 3AC is no longer a holder of GBTC, having sold all positions at an undisclosed time—likely at a loss.

Like Celsius, 3AC was also hit by stETH depreciation, losing value as stETH declined. Additionally, reports indicate 3AC was a major borrower of crypto assets—especially Bitcoin—leaving lenders with likely bad debts. Voyager Digital was one such lender, having extended a $660 million unsecured loan to 3AC. Voyager Digital has since also filed for bankruptcy.

3AC exemplifies the interconnectedness of the crypto market, where relatively small shocks can have amplified effects in an over-leveraged, under-reserved ecosystem. Terra was just one of many exchanges and systems—it couldn’t exist in isolation. Critics note that 3AC borrowed from too many lenders, many of whom sourced deposits from retail investors, escalating debts beyond manageable levels. Thus, 3AC’s investment decisions impacted not only institutional clients but also ordinary users across networks that lent recklessly to 3AC.

Beyond poor investment choices, 3AC has been criticized by Singapore authorities for making misleading and false disclosures to lenders in order to secure additional loans—allegedly engaging in fraud.

As Decrypt reported:

“In an affidavit submitted on June 26, Blockchain.com’s Chief Strategy Officer Charles McGarraugh revealed that 3AC co-founder Kyle Davies told him on June 13 that Davies wanted to borrow 5,000 more bitcoins from Genesis, worth about $125 million at the time, ‘to pay a margin call to another lender.’ Such behavior is typical of Ponzi schemes, where money from later investors is used to pay earlier ones.”

This highlights the lack of prudent oversight in crypto lending—a failure by the industry to monitor risky behaviors pursued by major players chasing quick returns.

5. Broader Market Impact

The crypto collapse was exacerbated by the current global economic downturn. Rising interest rates, war, and shortages of energy and food have influenced consumer expectations—impacting market behavior, including in crypto assets.

As global financial prospects dim, consumers seek lower-risk, safer investments—including safer crypto and traditional options. This includes shifting toward less risky crypto products, such as ETH instead of stETH.

If consumers’ crypto deposits lack any safety net, it fuels panic around exchanges and staking pools—exactly what Celsius and Anchor faced. Regulators are increasingly aware of market manipulation, highlighting the need for checks and balances among key institutional players in the crypto market. Regulatory uncertainty further worsens consumer sentiment, pushing markets toward investments perceived as safer.

The crypto market is part of the global economy and thus experiences cycles influenced by general consumer sentiment. Nevertheless, these boom-and-bust cycles could be mitigated through regulatory intervention, ensuring systemic shocks don’t have catastrophic impacts like those recently seen.

6. The Need for Regulatory Reform

Economists offer conflicting views on why and when regulation is necessary. These theories apply not only to banks but also to crypto exchanges and institutions offering bank-like services—accepting deposits, generating interest, and lending. Common themes include monopoly, information asymmetry, and externalities.

Negative externalities refer to costs borne by third parties due to economic transactions. In banking, examples include: (i) bank runs on solvent institutions; (ii) economic distress or collapse caused by bank failures; and (iii) increased costs of government-provided deposit insurance.

Monopolistic dominance in banking leads to unfair outcomes for consumers, as dominant players face no competitive challenge and can manipulate markets.

Information asymmetry involves exploitation of consumers due to lack of transparency, leading to unfavorable decisions. Consumers typically lack the sophistication of banks in understanding investments and risks, requiring protection.

Recent shocks clearly demonstrate all three issues in the crypto market. Following multiple exchange and fund collapses, the market clearly faced economic distress. Concentration among a few major players shows their ability to manipulate markets—on-chain or via social media (consider the few wallets that destabilized Anchor Protocol). Interconnectedness means one entity’s failure cannot be isolated from others. Exchanges and investment funds lack transparency—consumers don’t know where their funds go or fully understand the information provided—clearly an issue of information asymmetry.

All these issues provide strong justification for aligning industry regulation with that of traditional finance—protecting consumers and providing effective remedies when losses occur.

6.1. Remedies in Traditional Finance

6.1.1. Central Bank Insurance

After the Great Depression, many central banks adopted mandatory deposit insurance, requiring banks to purchase minimum coverage to protect consumers in case of bank failure.

This provides security for depositors and strengthens confidence in banks during financial hardship, reducing bank runs. In countries without explicit deposit insurance, central banks may still exercise discretion to compensate depositors who lost funds in failed banks—on a case-by-case basis.

Deposit insurance acts as a safety net—a remedy available to consumers in traditional banking, but not to depositors on crypto exchanges like Celsius.

6.1.2. Prudential Regulation

In traditional finance, banks are subject to central bank authority and prudential regulation—ensuring they operate legally and responsibly. It would be irresponsible for central banks to insure private banks engaging in high-risk activities and then use taxpayer money to bail them out when they fail.

A robust regulatory regime that sets rules for accepting public deposits and supervises their use can reduce bank failures and increase public confidence in the banking system.

Many central banks worldwide regulate private banks based on capital, asset quality, management soundness, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to risk (provided risks are properly managed). These criteria can equally apply to crypto investment platforms and exchanges.

6.2. Remedies Available to Consumers

In traditional finance, most consumers harmed by imprudent (or illegal) bank behavior can seek help from relevant regulatory bodies.

Currently, in most jurisdictions, when an exchange or investment vehicle files for bankruptcy, consumers have rights only as unsecured creditors. As noted, they usually rank near the end of a long creditor list, meaning recoveries are minimal.

Consumers must also review their contracts with exchanges or investment firms to identify possible remedies. Unfortunately, many contracts—especially fine print clauses—are broad and disclaim liability for losses consumers may suffer. Currently, consumers should read all applicable investment terms carefully and refrain from investing unless comfortable with the worst-case scenarios covered by those terms.

Of course, if fraud is involved in any corporate transaction causing consumer investment losses, compensation may be sought through civil courts. However, this is a lengthy and expensive process, often not worth the time and cost for most consumers.

Like any industry, there are inherent security risks. Because crypto transactions are often jurisdiction-free and anonymous, tracing hackers is extremely difficult. This is a factor regulators must consider when implementing minimum oversight—potentially holding exchanges accountable for losses in consumer wallets.

7. Pending Regulations

Most global jurisdictions have plans to regulate cryptocurrencies. Some aim to classify them as commodities, others as legal tender, and others as financial products.

In the European Union, anti-money laundering regulations require crypto asset service providers to obtain licenses to operate. However, this differs from financial service licenses and does not carry equivalent reporting standards. The Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) bill has been submitted to the European Parliament and is expected to pass by 2024—it aims to bring crypto asset service providers in line with traditional financial institutions.

MiCA has the following objectives:

1. Provide legal certainty for crypto assets not covered by existing EU financial services laws, where clear demand exists.

2. Establish uniform rules across the EU for crypto asset service providers and issuers.

3. Replace current national frameworks applicable to crypto assets with EU-wide financial services regulations; and

4. Set specific rules for so-called “stablecoins,” including e-money.

Crypto assets already classified as financial instruments under the EU’s Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) or as e-money under the Electronic Money Directive (EMD) fall outside MiCA’s scope. MiCA aims to harmonize regulation and “capture” crypto asset activities not covered by existing frameworks.

The bill specifically mandates licensing for crypto asset service providers and imposes reserve requirements on stablecoins. MiCA doesn’t cover every aspect of the crypto world, but it addresses major market concerns—particularly services offered by crypto exchanges—and establishes clear consumer protection responsibilities.

Globally, the crypto industry would benefit from regulation that imposes prudent standards (setting thresholds and requiring transparent reporting for safe operations) and provides consumers with clear avenues to enforce their rights, backed by identifiable regulatory authorities. Such regulations could curb excessive risk-taking and restore market confidence in the industry.

8. Conclusion

The recent downturn in the cryptocurrency market reveals systemic flaws that require regulation to curb irresponsible behavior and protect consumers.

Terra’s collapse was not isolated—it marked a turning point for over-leveraged crypto hedge funds and exchanges. Celsius was one such case, not only overexposed to Terra but also one of the main contributors to the bank run on Anchor Protocol. Exposure to stETH, another de-pegging instrument, compounded Celsius’s losses.

3AC may be one of the clearest examples of cascading effects across the industry. As a major borrower facing bad debts on exchange ledgers, 3AC’s over-leveraged positions triggered liquidation. Behind all the turmoil lies the irresponsible conduct of executives at these funds and exchanges—gambling with other people’s money while facing no real consequences.

Participants within the crypto market may be private entities like hedge funds, yet they significantly influence the overall market due to their large share of market resources. As we’ve recently seen, regulating all actors capable of destabilizing the market can provide much-needed protection for consumers and support long-term market stability.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News