The Technological History of ZK: Discovering the Next Billion-Dollar Application Built Upon It

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Technological History of ZK: Discovering the Next Billion-Dollar Application Built Upon It

The first article in this series will start with zero-knowledge proofs, moving beyond the conventional notion that ZK can only be applied in L2 contexts, and provide you with a fresh, systematic understanding.

The focus of the crypto world has shifted multiple times—from Bitcoin, Ethereum, DeFi, NFTs, and the metaverse to Web3—yet there has been a notable lack of attention toward cryptography itself. Aside from Bitcoin's elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), which enjoys modest public recognition, most cryptographic algorithms remain confined within academic research circles and developer communities.

R3PO believes this state is insufficiently decentralized and will severely hinder the further expansion of Web3. Cryptography is foundational infrastructure for blockchain; it should not be monopolized by a small elite but rather expanded into broader domains.

R3PO aims to redefine technical terminology with a new narrative paradigm that balances professionalism with readability, striving to help institutional investors and project teams uncover emerging investment opportunities, entrepreneurial directions, and entry points, ultimately discovering untapped α returns.

Zero-knowledge proof (ZK) technology, recently gaining widespread attention, remains an evolving and rapidly innovating niche field. Yet its underlying technology offers vast application potential, making a comprehensive overview critically important.

The concept of zero-knowledge proofs is not new. A closer look reveals that it has already undergone 40 years of development, giving rise to various models and applications.

In the Web3 era, as early as 2017, Vitalik Buterin recognized the potential of ZK technology on Ethereum. More recently, Starkware raised $100 million, bringing its total funding to $225 million—demonstrating that institutions are valuing ZK at the level of public blockchains. This will be a long-term battlefield, revealing even more investment opportunities.

Looking ahead two decades, R3PO believes ZK development possesses at least a full 60-year lifecycle. Therefore, mapping out the entire trajectory of ZK requires tracing its origins to better understand its developmental logic and identify future opportunities.

This inaugural article in the series will begin with the fundamentals of zero-knowledge proofs, moving beyond the conventional perception that ZK applies only to Layer 2 solutions, offering readers a fresh, systematic understanding.

Zero to Start: The Assembly of ZK

1982: Concealing Wealth, Yet Determining Rank

The pursuit of wealth is ancient. As Xiang Yu once said: "To achieve riches and honor without returning home is like wearing fine clothes at night—no one sees." However, excessive wealth invites envy. Is there a way to compare who is richer without revealing the actual amount?

In 1982, Yao Qizhi, later a Turing Award winner, pondered this very question—the now-famous Millionaire’s Problem. Without delving into the mathematical details, its basic mechanism works as follows:

Alice and Bob each pick numbers i and j representing their wealth, ranging from 1 to 10;

Alice applies a one-way encryption to i and sends the encrypted result k to Bob, giving Bob a value correlated with i;

After processing k, Bob generates a new value m and sends it back to Alice, who can then determine the relationship between m and i.

This process can be extended so both parties eventually reach a conclusion without fully exposing their private information.

Of course, this simplified description isn't exhaustive, but it illustrates a key point: we can indeed perform computations between two parties without revealing sensitive data. Extending this to multiple parties and larger ranges leads directly to the classic Secure Multi-party Computation (MPC) problem.

The Millionaire’s Problem serves as a starting point for ZK discussions:

It satisfies the definition of zero-knowledge by allowing comparison without disclosing wealth;

It examines direct interaction between participants without relying on a third party for evaluation.

1985: Birth of Zero-Knowledge Proofs

In 1985, Goldwasser, Micali, and Rackoff formally introduced the Zero-Knowledge Proof model—specifically, the “interactive zero-knowledge proof.” In simple terms, it allows verification of truth or magnitude through repeated interactions using ZK techniques.

Here, “zero knowledge” does not mean no information is transmitted. Using Alice and Bob again as an example, they may take turns being verifier and prover, but the exchanged data must have zero correlation with the actual wealth values. Thus, “zero knowledge” refers to zero relevance—not zero communication.

“Interactive” means multiple rounds of exchange are allowed, continuing until a correct outcome is reached.

At this point, the modern concept of ZK took its first formative step. All subsequent developments would build upon or refine this foundation.

1991: Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge Proofs

By 1991, Manuel Blum, Alfredo Santis, Silvio Micali, and Giuseppe Persiano proposed non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs. As the name suggests, the key advancement was enabling proofs without requiring back-and-forth interaction—verifying the truth of a statement in a single transmission. This may seem counterintuitive, but consider this elegant analogy:

After achieving financial freedom, Alice and Bob become mathematicians. Alice leaves web2 behind to travel across web3, continuing her ZK research on the go.

Suppose Alice discovers a new theorem and sends Bob a postcard to prove her breakthrough.

This is a non-interactive process—a one-way transmission from Alice to Bob. Even if Bob wanted to reply, he couldn’t, because Alice has no fixed or predictable address and moves before any mail reaches her.

We agree that upon receiving the postcard, we can confirm the statement “Alice made a new research breakthrough” is true—even without reading its contents.

Non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs reduce interactions to at most one round, enabling offline and public verification. The former laid the groundwork for Rollups, while the latter aligns with blockchain’s broadcast mechanism, avoiding resource waste from redundant computation.

At this stage, ZK matured into a solid theoretical framework. However, ZK remained primarily a subject of mathematics and cryptography, with little connection to blockchain. It wasn’t until Bitcoin emerged that the combination of cryptographic techniques and blockchain became a research direction—and ZK stood out as a leading candidate.

Notably, Satoshi Nakamoto did not oppose the use of ZK in Bitcoin; rather, ZK technology at the time was simply immature. Hence, the more conservative ECC algorithm was adopted. Nevertheless, ZK can be directly applied to Layer 1 blockchains—examples include Zcash, Mina, and Ethereum’s Istanbul upgrade, all involving zero-knowledge proofs.

First Encounter: SNARK Enters Blockchain

2010–2014: Zcash – Practical Applications of SNARKs (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge)

After Bitcoin’s emergence, security and privacy became the initial perceptions of blockchain. A wave of privacy-focused public chains and applications followed, such as Zerocash/Zcash using SNARKs, and Monero employing Bulletproofs (BP).

In 2010, Groth implemented the first ZK based on ECC with O(1) constant complexity—what we now call ZK-SNARKs or ZK-SNARGs.

SNARGs: Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments

SNARKs: Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge

From an application standpoint, the key improvement lies in “succinctness”—compressing the size of the proof. In Zcash, the program circuit is fixed, so polynomial verification is also fixed. This allows setup to occur once, with subsequent transactions reusing the same structure by changing only inputs.

In 2013, the Pinocchio protocol improved efficiency to minutes for proof generation and milliseconds for verification, with overhead under 300 bytes—marking the first real-world deployment of ZK-SNARKs on blockchain.

This demonstrated ZK’s viability in privacy applications. R3PO believes privacy-focused projects will eventually gain standalone value beyond L2. Aztec has shown the feasibility of privacy-preserving DeFi, and despite Tornado Cash’s sanctions, on-chain financial privacy remains a strong unmet demand. Investment opportunities in this space remain underexplored and worth watching.

Additionally, the privacy coin project Zerocash further refined related algorithms using zk-SNARKs optimized by SCIPR Lab. Under theoretical conditions, it can hide payment sources, recipients, and amounts, with transactions under 1KB and verification under 6ms.

Mina: Recursive ZK for Data Compression

Unlike Ethereum L2 solutions, Mina is a high-performance L1 public chain whose nodes require only 22KB of storage. This extreme compression is achieved by heavily leveraging recursive ZK proofs—each message carries prior validation results.

Step 1: Use zk-SNARKs to prove node validity, storing only the proof;

Step 2: Through recursive calls, ensure valid propagation and retrieval of node validity without retaining full historical data, achieving maximum data compression.

Transmitting validity instead of storing full-node data proves effective in Mina. In Ethereum L2, ZK-Rollups achieve validity proofs by batching multiple transactions into a single settlement. Extending this idea, L3 layers or dApps can be built atop L2—such as dYdX running on StarkEx and ImmutableX built on Starkware—showcasing ZK’s expansive potential. This sector remains undervalued, offering long-term investment prospects.

At this point, the core technical components of ZK-Rollup are largely complete. With sufficient foundational knowledge of ZK, we can summarize its key characteristics:

Non-interactive: Requires only a single verification, which can then be broadcast network-wide;

Zero-knowledge: Does not reveal intrinsic data features, enabling public dissemination;

Knowledge: Refers to information that is not public or easily obtainable, possessing unique value such as economic or privacy value;

Proof: Mathematically verified, with security rigorously tested over years of research and practice.

Combining these traits, we see that ZK is naturally suited for L2 scaling—but not limited to it. Other ZK applications will be explored in upcoming articles; stay tuned.

Clash of Titans: STARK Will Eventually Supplant SNARK

ZK-STARK: A Seed Player with a Decade-Long Development Curve

The main difference lies in the “S” of STARK, standing for Scalability—targeting complex, large-scale data scenarios. Nonetheless, it remains an evolving technical path.

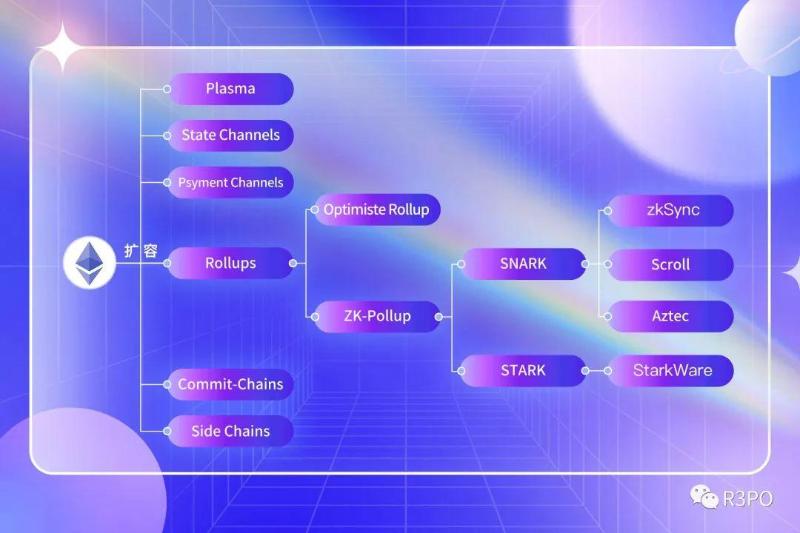

While this article won’t delve deeply into differences among specific L2s, one fact is clear: apart from StarkWare, other L2 projects—including zkSync, Aztec, Loopring, and Scroll—follow the SNARKs path.

The reason? STARK’s development difficulty is extremely high—currently only StarkWare has the capability to build it independently. Yet its advantages are equally significant: compared to SNARKs, STARK supports heavier computation loads and offers higher security when handling large datasets—ideal for gaming, social platforms, NFTs, and similar use cases.

Moreover, the STARK approach is quantum-resistant—a feature with potential to disrupt industry dynamics over the next decade. Bitcoin’s ECC algorithm cannot fully resist quantum attacks. Integrating zk-STARKs would significantly enhance security.

We can summarize Ethereum’s L2 landscape: short-term dominance by Optimistic Rollups, zk-SNARKs prevailing in five years, and zk-STARKs ultimately winning out in ten.

ZK-Rollup: Data Aggregation, Information Deep Dive

After covering zk-STARKs, all technical aspects of L2 scaling are now in place—only Rollup remains to be explained. Rollup leverages ZK’s verification mechanism while minimizing data requirements: L1 handles consensus and settlement, while L2 manages day-to-day operations. Users need not interact directly with L1, resulting in user experiences closely resembling today’s mainstream apps.

Further, after bundling transactions, Rollup encrypts the verified information into “knowledge” and submits it to L1—thereby overcoming the blockchain trilemma of security, decentralization, and scalability.

Conclusion

Starting from the Millionaire’s Problem and transitioning through MPC, we entered the realm of zero-knowledge proofs. Due to economic inefficiency, interactive ZK proofs are poorly suited for on-chain activities, while non-interactive variants gradually became dominant.

With the evolution of Zcash, SNARKs found practical applications, transforming ZK from a purely cryptographic research topic into an engineering tool within blockchain—delivering benefits in privacy, security, and efficiency.

Ethereum’s scaling needs elevated ZK to power L2 solutions. The Rollup architecture outcompeted alternatives, while zk-STARKs began gaining momentum—poised to unlock broader use cases in mining, GameFi, NFTs, and beyond.

Beyond Ethereum, new models continue to emerge—such as customizable modular Rollups. For instance, Eclipse recently raised $15 million, aiming to support Move language and Solana networks; Scroll secured $30 million to build an EVM-equivalent ZK-Rollup.

The driving force behind these new narratives is growing recognition of ZK technology. Broadly speaking, ZK is a “large and comprehensive, long-term” domain. Repeated large funding announcements reflect rising market acceptance. Yet overall, this remains a nascent field—even technically, it hosts competitive sub-schools. Investment opportunities endure, whether embedded in foundational infrastructure or realized in concrete applications, awaiting continuous discovery.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News