Japan No Longer Hesitates to Make Its Move into Web3

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Japan No Longer Hesitates to Make Its Move into Web3

In the middle game of Web3, Japan is no longer hesitating.

By aya

On September 22, Astar founder Soichiro Watanabe announced on his blog that Astar’s native token had passed strict reviews by Japan’s Financial Services Agency (FSA) and the Japan Virtual and Cryptoasset Exchange Association (JVCEA), and would be listed on Bitbank, a domestic Japanese exchange.

In his post, he wrote, "Listing in Japan was never our goal—it's just the starting line." He also boldly proclaimed, "What I want to do is create products representative of this era on a global scale. Within our company, we often say 'Shine Like A Star'—just like Toyota and Sony. We want the next generation to aspire to become Astar on the world stage."

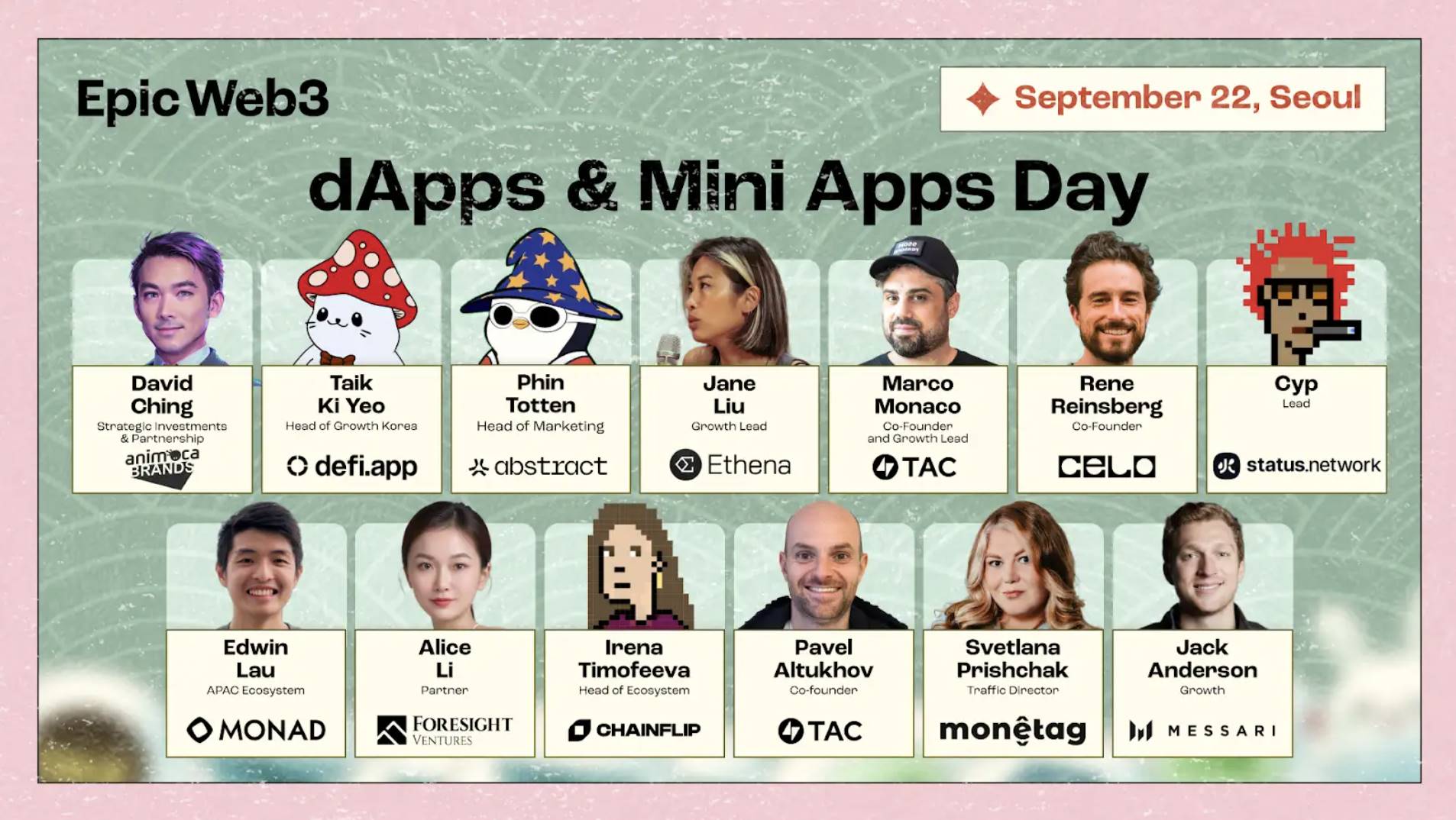

However, compared to globally renowned industrial giants such as Sony and Toyota, Astar's domestic listing has not stirred much reaction within the crypto community. People are more focused on the future of ETH fork chains after the Merge and the upcoming Token2049, Asia’s largest blockchain conference in Singapore.

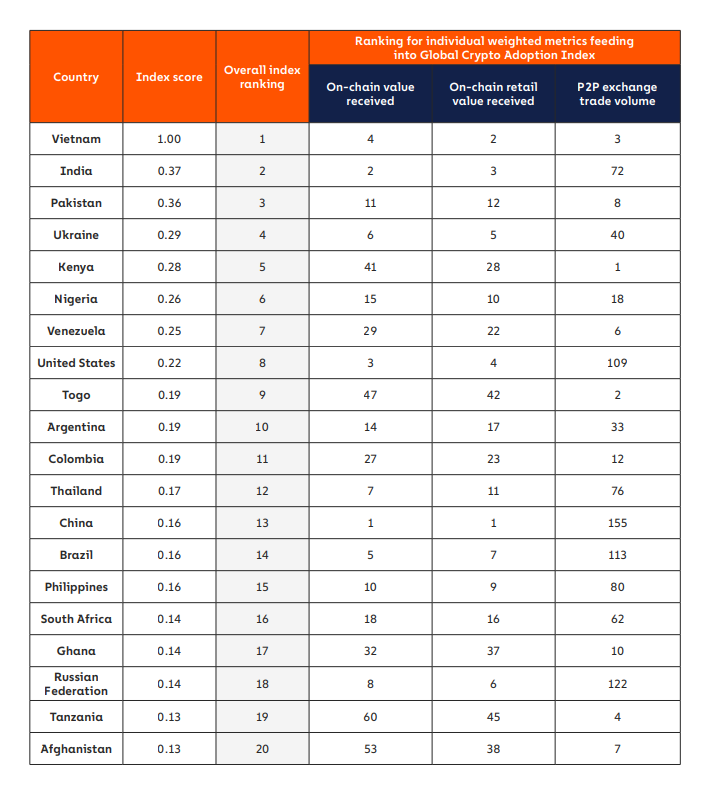

Reality is harsher than any story. According to Chainalysis’ “2021 Global Cryptocurrency Adoption Index,” Vietnam and the Philippines ranked first and second in Asia, while the U.S. ranked fifth. Japan, meanwhile, fell outside the top twenty, ranking even below Nepal and Kenya.

Due to its geographical isolation and lack of resources, the concept of “preservation” permeates every level of Japanese society, along with rigid hierarchies and cumbersome procedures—because once the existing order is disrupted, it is nearly impossible to rebuild. Yet Japan has always remained at the forefront of technological advancement, giving birth to modern innovations like the Shinkansen, Walkman, and pocket calculator.

For Japanese people who have yet to fully grasp the crypto industry, something like Bitcoin—an innovation transcending traditional financial systems—is both novel and concerning. Because of this, Japan’s policy stance on Web3 remained hesitant and inconsistent during its early stages.

But now, halfway through Web3’s evolution, Japan is no longer hesitating.

The Beginning

Japan’s earliest connection with Web3 traces back to the invention of Bitcoin. When the white paper was published, the distinctly Japanese pseudonym “Satoshi Nakamoto” emerged, and Nakamoto himself claimed to reside in Japan. In July 2010, programmer Jed McCaleb, originally planning to build a Magic: The Gathering trading site, repurposed a purchased domain for a new cryptocurrency exchange.

Thus, Mt.Gox became a household name in the crypto world and quickly rose to become the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, processing millions of dollars in transactions flowing into Tokyo daily before spreading across the globe via internet lines.

Believers and enthusiasts began further experimentation.

In 2013, Monacoin was first revealed on the Japanese forum 2chan. Forked from Litecoin, it claimed to be Japan’s first cryptocurrency and aimed to become the sole digital payment method within Japan. Like many early projects, its founder remained anonymous, using only the alias “Mr. Watanabe.” Owing to its use of a cartoon cat as the token icon, Mona attracted widespread attention in 2014.

On New Year’s Day 2014, Monacoin officially launched, detailing its origin and vision. Eight days later, Yusuke Kano, a former Goldman Sachs derivatives and bond trader, founded the exchange BitFlyer in Tokyo. Staffed largely by ex-Goldman employees, the company grew rapidly during the wild west era and became Japan’s largest exchange within two years.

But the good times didn’t last long—a hacking incident brought the mighty Mt.Gox crashing down from its pedestal. Despite efforts to recover over 700,000 stolen bitcoins, the damage was irreversible. Mt.Gox ultimately declared bankruptcy, and an industry giant collapsed overnight.

Meanwhile, Mona began attracting significant local media attention. NHK reported how someone used Mona to purchase land and build a dedicated shrine—similar to how Flying Spaghetti Monster followers construct their churches—and even designed a logo for it.

To protect individual investors from suffering massive losses in incidents like Mt.Gox again, Japan took legislative action. In 2014, the FSA established a dedicated task force to investigate cryptocurrency payments and settlement services in Japan. The group completed its work the following year, submitting a final report that laid the foundation for future cryptocurrency legislation.

That same year, the Japan Digital Asset Association (JADA) was announced. Comprised of blockchain and crypto startups and entrepreneurs, JADA aimed to foster a healthy environment for cryptocurrency trading and business. Whenever the FSA needed to draft crypto-related laws, JADA would “lobby and assist in setting the rules.”

In March 2016, Parliament passed amendments to the “Payment Services Act” and “Funds Settlement Act,” legally recognizing cryptocurrencies under the term “virtual currency.” The law required exchanges to register with the government and mandated that virtual currency exchanges “notify relevant authorities upon detecting suspicious transactions.”

Six months later, JADA restructured into a new organization—the Japan Blockchain Association (JBA)—consisting of two divisions:

- One focused on cryptocurrency-related matters including consumer protection, taxation, and financial regulation, led primarily by representatives from bitFlyer, Coincheck, and Kraken Japan;

- The other handled definitions and policy recommendations for non-monetary blockchain technologies, with major responsibilities held by companies including Microsoft Japan, payment gateway GMO Internet Group, and blockchain cloud platform Orb.

On April 1, 2017, the revised laws officially took effect. Prior to this, all 21 exchanges operating domestically in Japan were classified as “virtual currency exchanges.” The law allowed these unlicensed exchanges to operate temporarily as “provisional registrants” while beginning applications for full licensing with the FSA.

From then on, the emerging cryptocurrency industry formally fell under the regulatory authority of the FSA.

Rules and Rule-Breakers

Yet regulatory intervention failed to prevent repeated thefts. In January 2018, domestic exchange Coincheck was hacked, resulting in the theft of $500 million worth of NEM tokens, making it one of the largest cryptocurrency heists in history. The incident sent shockwaves throughout Japan.

In April that year, 16 registered domestic cryptocurrency exchanges—including BitFlyer, Coincheck, and Coinbase Japan—announced the formation of JVCEA (Japan Virtual and Cryptoasset Exchange Association), receiving official recognition. The FSA hoped self-regulation by enterprises would ensure stable industry growth, while companies could dynamically assist in policymaking to better protect investor safety.

Hacking attacks continued—in September, Osaka-based exchange Zaif suffered a breach, losing over $60 million in cryptocurrencies including BTC, ETH, and Mona. Of the stolen funds, 68% belonged to customers. According to investigators, hackers stole the assets directly from the company’s hot wallet.

These two incidents fundamentally shifted the government’s attitude toward the industry. Quickly, the FSA announced it would implement “stricter review procedures” for licensing applicants and “continue inspections, removing companies showing no improvement.” Exchanges including BitFlyer were ordered to halt new customer registrations due to “indifference toward money laundering and terrorist financing activities,” and were required to upgrade their KYC systems. Some exchanges even withdrew pending license applications.

Meanwhile, JVCEA and the FSA conducted inspections and found numerous exchanges still harbored serious security vulnerabilities. As a result, the FSA issued zero new licenses throughout 2018, forcing many exchanges—including Binance—to face a stark choice: relocate or shut down.

The FSA found itself in an awkward position—nearly all policy recommendations came from JBA and JVCEA, while implementation relied heavily on large firms within these organizations. This placed Japan’s crypto industry in an early state of “regulatory capture.”

Because the FSA frequently relied on industry insiders rather than conducting independent research when formulating regulations, many areas effectively escaped oversight. For example, there was no binding standard for asset storage—only a vague “requirement” that exchanges store cryptographic keys for digital assets in “cold wallets,” such as offline USB drives, provided doing so did not cause “excessive inconvenience” to users. This indirectly contributed to the Coincheck and Zaif breaches.

This awkward situation persists today. At a late-2022 FSA meeting, officials twice warned JVCEA about poor communication among board members, secretariat staff, and operator members, citing mismanagement and sluggish progress. In some cases, JVCEA took six months to a year to review a single cryptocurrency—effectively the entire lifecycle for most projects.

JVCEA has its own challenges: office staff are mostly retired personnel from banks, securities firms, and government agencies—not professionals from crypto companies. Many are encountering crypto “for the first time in their lives”. Internal conflicts have escalated to the point where staff spontaneously formed a union to “protect their legal rights.”

Local Enterprises Forging Their Path

When discussing Japan’s blockchain development, one figure stands above all others: Yusuke Kano, current chairman of JBA and founder of BitFlyer. After graduating from the University of Tokyo, Kano joined Goldman Sachs, working on payment system development. He later left and returned before finally departing Goldman for the second time in 2014. After securing 160 million yen in funding, he founded the domestic exchange BitFlyer in Tokyo. Unlike Mt.Gox, which was French-run and targeted international markets, Kano and BitFlyer focused primarily on domestic growth from the outset.

Months later, Mt.Gox collapsed, and domestic exchanges like BitFlyer began carving out new territories atop the fallen giant.

Kano recruited numerous former Goldman colleagues, applying his traditional finance experience to the crypto exchange. Two years later, BitFlyer became Japan’s largest crypto exchange and briefly the world’s largest Bitcoin exchange. It also began expanding overseas. In November 2017, BitFlyer announced it had obtained licenses to operate in over 40 U.S. states. The following January, it secured EU Payment Institution authorization, entering Europe. Thus, BitFlyer became one of the world’s most compliant exchanges, holding approvals from Japan, the U.S., and the EU—the three strictest financial jurisdictions.

At the same time, BitFlyer actively promoted cryptocurrency retail payments in Japan, forming partnerships with retailers and mobile payment providers. Physical stores including AMENRO LA FIESTA, Bic Camera, and Numazu Port began accepting Bitcoin payments.

Shortly after Kano founded BitFlyer, a young man near Keio University—not far from the University of Tokyo—was preparing to travel to India. There, he first experienced firsthand the severity of poverty and environmental issues, sparking a desire to solve them. He later studied blockchain technology and knowledge in the United States.

Upon returning to Japan, he enrolled at Kano’s alma mater and co-founded Stake Technologies with a friend, launching their technical journey on the Polkadot ecosystem. But they’re better known for their product—Astar, a multi-chain, multi-virtual-machine DApp hub built on Polkadot. For a long time, Astar was the only widely recognized “Made in Japan” project in the crypto space.

Almost simultaneously as regulation began rolling out, traditional Japanese corporations also turned their attention to Web3—a field still untapped in potential. A prime example is Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Japan’s largest bank by assets, which has frequently collaborated with crypto firms like Animoca and plans to launch a yen-backed stablecoin. Many executives formerly at traditional firms have joined blockchain startups, bringing resources from their previous companies. For instance, Jasmy, a national initiative, brought on Kunihiko Anzai, former President and CEO of Sony, as Representative Director. Meanwhile, the gaming-focused chain Oasys enlisted CEOs from legacy companies like Bandai Namco and Sega as advisors.

Long Road Ahead

Newly appointed Prime Minister Fumio Kishida holds a significantly more positive view toward Web3 and cryptocurrencies than his predecessors. During a House of Representatives session in May, Kishida stated: “The arrival of the Web3 era may drive economic growth in Japan.” Earlier, during a visit to the UK, he mentioned a new “system reform” to promote emerging industries, including Web3-related infrastructure. Kishida also established a dedicated Web3 policy office under the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) to advise on policy and industrial development.

Current ruling party politicians—the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)—are taking even more aggressive steps, determined to bypass the slow and bloated bureaucracy to directly advance the industry. The LDP established a special NFT policy task force this year, initiated by lawmaker Masaaki Hirai and led by former Digital Transformation Minister Takuya Hirai. In April, the group released an NFT white paper titled “Japan’s NFT Strategy in the Web3.0 Era,” declaring that “the advent of Web3.0 presents a tremendous opportunity for Japan,” and offering recommendations on secondary sales, intellectual property, and crucially, tax reform. The task force also proposed appointing a dedicated Web3 minister and establishing an inter-agency advisory group to meet the evolving needs of businesses and government agencies in Japan’s growing crypto market.

Politicians hope to establish an independent advisory system outside the interests of incumbent enterprises, aiming to reduce JBA and JVCEA’s influence over policymaking. They also have personal motives—after Shinzo Abe’s assassination, the fragile political balance within the LDP was shattered, and in this chaos, achieving visible results offers the best path to advancement.

Yet reform is far from easy—early entrants among large corporations resist weakening their policy influence. Meanwhile, as the U.S. and Silicon Valley reclaim dominance in the crypto world, Japan’s early regulatory advantages and leadership are gradually eroding. High tax rates continue driving local talent to the Middle East and Southeast Asia, while active competition from South Korea and Vietnam adds further pressure. For Japan, the path to Web3 development remains long and arduous.

Nevertheless, Japan is no longer conservative in the Web3 wave but is instead proactively striking forward. The island nation swings its baseball bat in the midgame, hoping for a home run in the next cycle.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News