A Monetary Standard That Bitcoin Pursues

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Monetary Standard That Bitcoin Pursues

Money stores our future choices. Choose your monetary unit carefully, and be wary of anyone who can print money faster than you earn it.

By: Thejaswini M A

Translated by: Block Unicorn

I’ve long wanted to read The Bitcoin Standard slowly—cover to cover—to see how it reshapes my thinking. It frequently appears in the background of Bitcoin discussions, hailed as foundational. People say things like “As Saifedeen explains…” only for you to realize they’re quoting not from the text itself, but from a meme or a cover screenshot.

So I’ll read the book in three parts. This is Part I.

We’re still in the early chapters—not yet at the full-blown critique later on, where fiat money allegedly ruins everything from architecture to waistlines. For now, Saifedeen Ammous is laying the groundwork, trying to convince you that money is a technology, that some forms of money are “harder” than others, and that history is essentially a process of selection in which harder options gradually prevail. If he succeeds in getting you to accept this, Bitcoin then emerges naturally—as the hardest money ever created.

I’m not fully convinced yet, but I must admit: it’s a tricky framework.

The book opens by stripping money of its romantic veneer, revealing its core essence. It is not a “social contract,” nor a “state creation.” It is simply a tool for transferring value across time and space—one people use without needing to think about it daily.

Ammous repeatedly emphasizes the concept of “salability.” A good monetary asset must be easily sellable, anywhere and anytime, without causing major losses. To be salable, it must satisfy three criteria: cross-spatially—so you can carry it with you and exchange it for what you need; cross-temporally—so it doesn’t rot or collapse in value; and cross-scalably—so it can serve any purpose, from buying a cup of tea to purchasing a house, without requiring a calculator or a sack of change.

Then comes the book’s decisive term: hardness. Hard money is money whose supply is difficult to increase. Soft money is easy to print. That’s it. Its core logic is simple: Why would you store your life’s work in something others can create at will?

You can feel the influence of the Austrian School in every sentence—but once you strip away ideology, the book leaves you with a genuinely useful question: If I invest my savings in X, how hard or easy is it for others to produce more X?

Once you view your own life through this lens—whether your savings are in rupees, dollars, stablecoins, Bitcoin, or any combination—it becomes nearly impossible to ignore.

Having established this framework, the book takes you on a tour of a miniature “Museum of Broken Money.”

The first exhibit is Yap Island and its Rai stones. These massive circular limestone discs—some weighing up to four tons—were quarried on other islands and painstakingly transported to Yap. Ammous writes that, for centuries, this system worked surprisingly well. The stones were enormous, difficult to move or steal. Everyone in the village knew who owned which stone. Payments were made by publicly announcing ownership transfers. These stones were “salable anywhere on the island,” because everyone on the island knew them; they were also durable over time, since acquiring new stones was so costly that existing stock “always far exceeded the amount newly producible within any given period… The stock-to-flow ratio of Rai stones was very high.”

Then, technology arrived.

In 1871, an Irish-American captain named David O’Keefe shipwrecked on Yap. After recovering, he left—but later returned with a large ship and explosives, realizing he could mass-produce Rai stones using modern tools. Villagers were divided. Chiefs declared his stones “too easy” to make, banned their use, and insisted only traditionally produced stones counted. Others disagreed and began mining newly discovered stones. Conflict erupted. Gradually, the stones ceased functioning as money. Today, most are used in ceremonial rituals.

This is a concise—and perhaps overly concise—parable. But it makes a point: Once a monetary commodity loses its hardness (i.e., once someone can cheaply mass-produce it), those who held it earlier effectively subsidize later entrants.

Beads and shells follow the same pattern. Aggry beads in West Africa were valuable precisely because they were scarce and labor-intensive to produce. Later, European merchants began importing them en masse from glass factories. Ammous describes how this importation “slowly but steadily” transformed them from “hard money” into “cheap money,” “destroying their salability and causing their purchasing power in African hands to decline over time—eventually impoverishing their owners, as their wealth transferred to Europeans, who could now acquire the beads effortlessly.”

Cowrie shells and wampum followed similar trajectories. Initially both were scarce, hard currencies—difficult to obtain, with high stock-to-flow ratios. Later, with the arrival of industrial ships, “their supply exploded, driving down their value and eroding their circulation over time”—by 1661, they had lost their status as legal tender.

You’ll find countless stories about cattle, salt, tally sticks, and cigarettes in POW camps. Each one does the same thing: train your intuition to recognize that if the supply of a new monetary unit can suddenly expand massively at near-zero cost, holders of existing stock are essentially making donations.

You can criticize these historical narratives for being too neat. Violence, politics, and culture barely appear. Everyone behaves like a hyper-rational economic agent with perfect memory. Yet as a device to instill suspicion toward easily printed money, it works.

Once you’re thoroughly spooked by shells and beads, metals arrive as the mature solution.

Metals solved many salability problems. Unlike grain, they don’t rot. They’re more portable than giant stones. They can be minted into uniform coins, simplifying pricing and accounting. Over time, gold and silver prevailed because they’re the hardest to inflate. Annual mining output adds only a tiny fraction to existing stock—so no single miner can devalue everyone’s savings.

Thus came the long era of metallic money—and later, paper money backed by gold. The book doesn’t dwell much on these details. Its aim is to make you feel that, once humanity discovered gold, it found a near-perfect monetary medium: portable, durable, divisible—and, most importantly, costly to produce.

You’ll soon see how this sets the stage for Bitcoin’s emergence. If you fully accept the claim that “under the physical and metallurgical constraints of its time, gold was the best material we could possibly produce,” then “Bitcoin is digital gold with even greater hardness” sounds entirely natural.

What intrigues me is that, in this section, gold reads less like a mystical object and more like a pragmatic workaround for physical limits. If you imagine ancient societies constantly asking, “How do we preserve the fruits of harvests or voyages in a form that endures across generations?” then gold is a relatively clever—though imperfect—answer.

This framing also benefits Bitcoin. It ceases to be “magic internet rocks,” and instead becomes “another attempt—using new tools—to solve the same old problem.”

The book hasn’t reached that point yet—but you can feel the runway being laid.

Then government-issued money arrives—and becomes the villain.

Until now, monetary collapses stemmed from external forces: new technologies disrupting rigid monetary systems, wiping out savers. Now the culprit comes from within: governments and central banks, legally empowered to print money unbacked by any scarce commodity.

Under this account, fiat money arises when governments realize they can fully decouple monetary symbols from real assets—retaining the unit of account while removing all constraint. Governments tell people their paper money has value because law says so, and taxes must be paid in it—not because it’s anchored to anything tangible.

Under gold or silver standards, currencies could depreciate or be devalued—but they wouldn’t suffer Zimbabwe-style collapses, where wages evaporate within months. Under fiat regimes, however, such collapses become possible—and some governments repeat them again and again.

Ammous devotes considerable space to explaining the social consequences of this phenomenon. To survive, people sell capital assets—eroding productive capacity. Long-term contracts collapse due to lack of trust. Political extremism festers amid anger and chaos. Weimar Germany stands as the classic case. Monetary collapse is merely the prelude to worse things.

It’s true that most fiat currencies depreciate against physical goods over the long term. In a sense, that’s baked into the design of the system.

Where my skepticism begins isn’t with the facts themselves, but with the book’s framing. Nearly every modern societal ill is blamed on fiat money. Central banks are almost exclusively portrayed as covert mechanisms taxing savers to subsidize borrowers. Any benefit of having a flexible lender of last resort is dismissed with a shrug—“but they’ll abuse it”—which may be valid, but isn’t the only question society needs to answer.

Even if you dislike central banks, the claim that “the entire twentieth century became a mistake the moment we abandoned full metallic standards” feels overstated.

What impressed me

So what practical value does Part I offer beyond adding more quotable lines to the timeline?

Oddly, it hasn’t made me more certain about Bitcoin. Rather, it’s clarified a question I hadn’t asked carefully enough before.

I rarely think about my money the way Ammous does. I consider risk and return, volatility, how much time I’m willing to spend on crypto versus duller pursuits—but I don’t sit down systematically to analyze who can print how much of each cryptocurrency I hold, or what rules govern that printing.

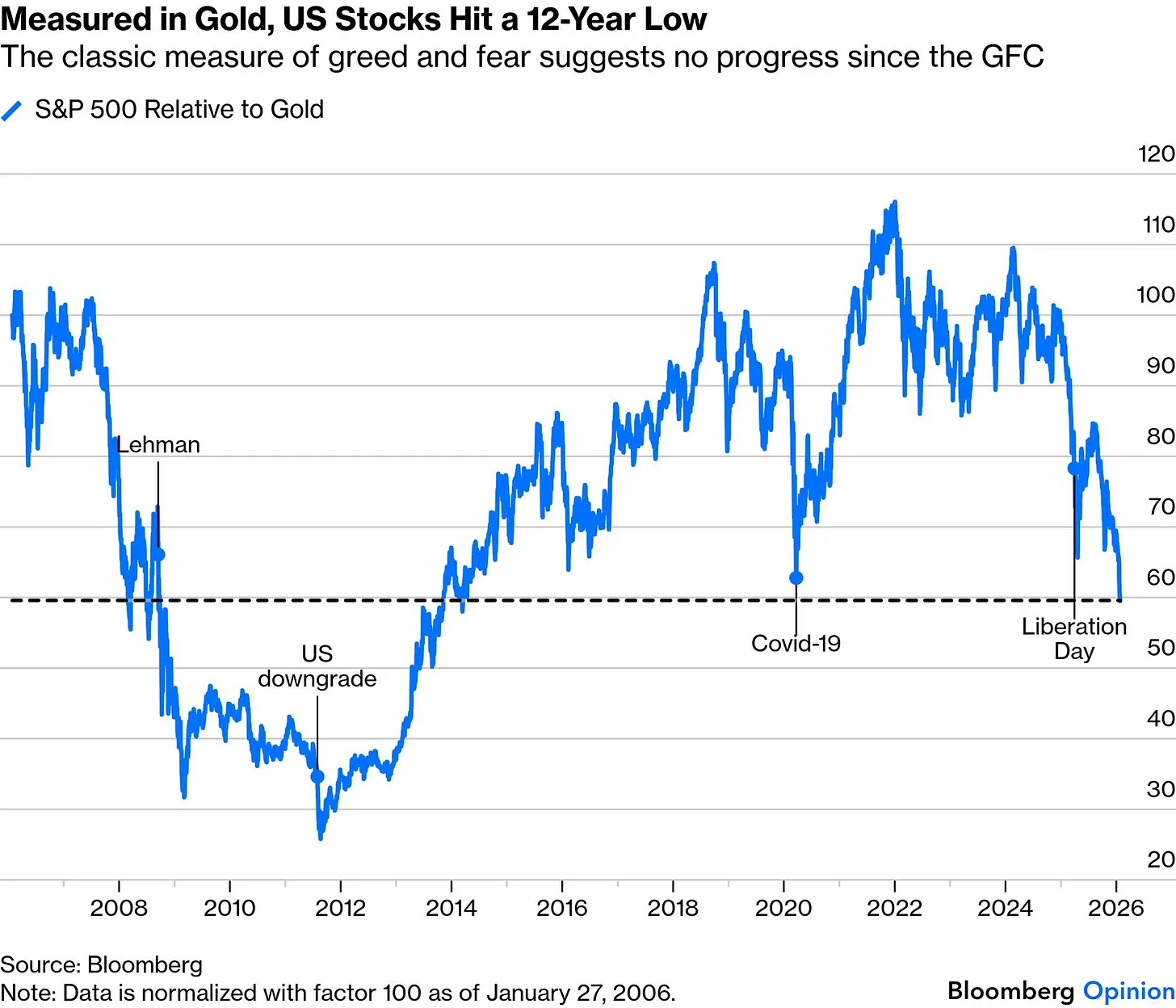

Then I saw a Bloomberg chart: the S&P 500, not priced in dollars—but in gold. It’s deeply unfair. Measured in gold, the U.S. stock market has regressed to levels seen over a decade ago—the post–global financial crisis era. All those dollar-denominated all-time highs, all the pandemic-era euphoria, dissolve into mere noisy fluctuations atop a flat line.

Once you grasp this, it’s hard to ignore Ammous’s simple, persistent point: performance is always “performance relative to what.” If your base unit is slowly depreciating, even record-high indices may represent stagnation when measured in a harder unit.

I realized the book omits much. It barely engages with credit as a social tool. It doesn’t mention that states don’t just destroy money—they also create the legal and military frameworks enabling markets to flourish. Nor does it explore the idea that some groups might sacrifice some economic resilience to gain greater shock-absorption capacity. Every issue circles back to one core question: Has the saver’s stake been diluted?

Perhaps that’s the point. This is a polemic—not a textbook. But I won’t pretend it’s the whole truth.

For now, I’m happy treating it as a lens—not a creed. Every time I see a central bank’s balance sheet, a new secondary bond issuance plan, or some “stable yield” product promising 18% USD returns, a Saifedeen-esque voice echoes in my ear: How hard is this money? And how many O’Keeffes have already dived underwater with explosives?

Right now, I just want to remember one thing: Money stores our future options. Choose your monetary unit carefully—and beware anyone who can print more money than you earn.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News