Crypto Payments 2049 | Can Stablecoins Bridge the Gap?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Crypto Payments 2049 | Can Stablecoins Bridge the Gap?

The greatest risk of new technology often lies not in its early stages, but in the middle phase as it moves toward mainstream adoption.

Author: Liu Honglin

At first, stablecoins did not carry grand narratives.

They were merely an "internal tool" within the crypto world: serving as a pricing unit on exchanges, forming the liquidity base in DeFi, and acting as a settlement medium in on-chain transactions. Their emergence resembled more of an engineering fix—faced with a highly volatile asset system, people needed a relatively stable anchor point to keep trading, lending, and liquidation functioning. Thus, stablecoins pegged their value to the U.S. dollar, making an otherwise highly unstable system appear at least locally "like a normal market."

For a long time, this phenomenon remained confined within the crypto ecosystem. Stablecoins solved problems specific to the crypto market; their risks, failures, and successes were all seen as "endogenous phenomena" of this emerging ecosystem. From the perspective of traditional finance, they appeared more like a technological byproduct—limited in scale, closed in usage, and controllable in impact.

But over the past two years, these boundaries have started to blur. Stablecoins have gradually moved beyond the crypto context, increasingly appearing in documents from international organizations, central banks, and regulatory bodies, entering discussions around cross-border payments, financial stability, and monetary sovereignty. The question is no longer just "how usable is it," but "could it affect the entire system." This shift did not arise from a sudden technological breakthrough, but because its scale and intensity of use have crossed a critical threshold: when a settlement tool consistently appears in cross-border fund flows, offshore markets, and real-world transactions in some emerging economies, it ceases to be a negligible technical arrangement and begins to exhibit spillover effects.

It is precisely at this moment that the nature of stablecoins has changed. They are no longer just an engineering component within the crypto world, but are evolving into a financial variable that institutions must seriously address. The issue is no longer "whether to use it," but "how to regulate it"; not "whether the technology works," but "whether the institutional framework can absorb it."

From this point onward, stablecoins have entered a new phase—they now stand at the very threshold of truly "crossing the chasm."

This is exactly why this article introduces the perspective of *Crossing the Chasm*. The reason *Crossing the Chasm* has been repeatedly cited in tech business history is not because it says "innovation matters," but because it captures a colder truth: the greatest risk for new technologies often lies not in the early stages, but in the middle phase of moving toward mainstream adoption. Early adopters are willing to bear risks themselves and try things out even when institutions are incomplete; early majorities, however, demand clear accountability, transferable risk, and recourse when things go wrong. The "chasm" in finance and payments is even deeper, because what’s being transacted here isn’t information—it’s assets, credit, and responsibility.

Thus, discussing "stablecoins crossing the chasm" does not equate to debating whether they will replace fiat currencies, nor whether they represent the "next generation of money." What this article focuses on is a more verifiable and institutionally significant question: Can stablecoins evolve from tools serving the crypto market into payment and settlement arrangements that can be absorbed within existing financial governance frameworks? To answer this, we must shift the discussion from "what technology can do" back to "what institutions allow and require," and dissect their real boundaries using traceable data and regulatory frameworks.

The full analysis will follow a clear path:

-

Chapter One defines the problem and research perspective;

-

Chapter Two establishes the institutional benchmark for "crossing the chasm" and public monetary arrangements;

-

Chapter Three uses on-chain and market data from the past two years to depict the formation and limitations of the early stablecoin market;

-

Chapter Four breaks down the institutional chasm facing stablecoins into three constraints: singleness, elasticity, and integrity;

-

Chapter Five compares how regulators in the EU, the U.S., and Hong Kong are building "limited-load-bearing" institutional bridges;

-

Chapter Six explains where stablecoins are most likely to achieve partial crossover using the "bowling pins" strategy;

-

Chapter Seven discusses how the structure of the financial system may be rearranged once partial integration occurs;

-

Chapter Eight returns to the Chinese context, clarifying institutional boundaries, realistic compliance paths, and viable professional roles;

-

Chapter Nine consolidates these observations into a sustainable tracking framework.

This report ultimately aims not to offer an emotional stance, but a set of testable conclusions: the future of stablecoins resembles a process of institutional negotiation and structural adjustment. Whether they can cross the chasm depends on their ability to transform "self-borne risk" into "institutionally absorbable risk," "market trust" into "accountable responsibility structures," and "technical efficiency" into "regulatable infrastructure" within limited scenarios.

Chapter One Research Background and Problem Definition

1.1 Institutional and Practical Context of Stablecoins as a Research Subject

In international finance and payment systems research, stablecoins have gradually evolved in recent years from a technical arrangement internal to crypto assets into a subject with clear public policy implications. This transformation is not due to disruptive technological breakthroughs in stablecoin design, but rather because their actual usage scale, functional spillovers, and potential systemic impacts have reached a level that regulators and international organizations can no longer ignore.

According to research and policy documents published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) between 2024 and 2025 on financial stability, fintech, and payment systems, stablecoin-related transaction activities have formed significant volumes in certain cross-border payment corridors, emerging markets, and crypto-intensive environments. Although their share of total global payments remains limited, their growth rate and application concentration significantly exceed those of most other crypto asset forms.

Unlike highly volatile crypto assets, the core design goal of stablecoins is not value appreciation, but price-stable value storage in digital environments through pegging to fiat currencies or low-volatility assets. Precisely for this reason, stablecoins have rapidly assumed key roles as units of account, media of exchange, and liquidity hubs within the crypto ecosystem, objectively forming a payment and settlement layer parallel to traditional banking deposit systems.

More importantly, stablecoin usage has clearly spilled over into areas of concern to traditional financial systems. In annual economic reports and related studies, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has repeatedly emphasized that the development of stablecoins poses new policy challenges to payment system structures, monitoring of cross-border capital flows, and arrangements for monetary sovereignty. Under this backdrop, stablecoins are no longer merely a technical question of "whether they should be allowed," but have become an institutional question of "how to incorporate them into existing financial governance frameworks."

1.2 Choice of Research Perspective: From Technical Discussion to Institutional Adoption

Existing research on stablecoins can roughly be divided into two categories: one focusing on technical and efficiency advantages such as low cost, high speed, and programmability; the other focusing on potential risks including financial instability, money laundering, sanctions evasion, and threats to monetary sovereignty. While both types provide important insights, neither fully explains a persistent reality: stablecoins have achieved high penetration in native crypto markets, yet have failed to achieve systematic adoption among broader economic actors.

To understand this gap, this article introduces the technology adoption lifecycle framework proposed in *Crossing the Chasm*. Since its publication in the 1990s, the book has become one of the most influential classics in the fields of tech industries, venture capital, and innovation research, widely used to explain the "mid-stage slowdown" experienced by information technologies, internet products, and fintech during commercialization. Its author, Geoffrey Moore, has long engaged in strategic and innovation diffusion research for high-tech firms, and his concept of the "chasm" has become a standard analytical tool for examining institutional and market discontinuities as new technologies move from niche to mainstream.

The core insight of this theory is that new technologies fail to achieve widespread adoption not necessarily because the technology itself is immature, but because different user groups differ structurally in their risk tolerance, expectations of responsibility, and dependence on institutional safeguards. Early adopters are willing to embrace new technologies primarily because they can bear the costs of failure themselves and do not rely on external institutional backing. However, when a technology attempts to enter broader economic sectors, the decisive factors cease to be efficiency or functionality, and instead become whether responsibilities are clear, risks are transferable, and institutional trust has been established.

Applying this analytical framework to stablecoin research helps explain a long-underestimated reality: the success of stablecoins in native crypto markets does not automatically mean they are ready to expand into real-world economies. The primary constraint facing stablecoins today is less about "insufficient market education" or "unclear regulation," and more about their failure to complete the critical transition from "usable by a few actors who self-bear risk" to "adoptable by most economic actors within an institutional framework."

1.3 Research Questions and Methodological Path

Based on the above background, this study conducts systematic analysis around three questions.

First, from the perspective of the technology adoption lifecycle, at what stage of development are stablecoins currently, and what identifiable characteristics define their main user structure?

Second, what specific institutional dimensions constitute the "chasm" that stablecoins face as they attempt to extend from serving native crypto markets to enterprises, financial institutions, and public sectors in the real economy?

Third, are the gradually emerging regulatory frameworks and industry practices providing real conditions for crossing this chasm, and what are their impact boundaries and inherent limitations?

Methodologically, this article combines international organization reports, central bank and regulatory documents, industry disclosures, and on-chain data analysis to cross-verify the development stage and institutional constraints of stablecoins, retaining citable sources at key judgment points for reader verification.

Chapter Two Theoretical Framework: Technology Adoption and Public Monetary Arrangements

2.1 Technology Adoption Lifecycle and Institutional Trust

The *Crossing the Chasm* theory identifies the most critical rupture point in technology diffusion as occurring between early adopters and the early majority. The former typically possess specialized knowledge and higher risk tolerance, willing to use new technologies even under incomplete institutional conditions; the latter, however, depend on mature product forms, clear responsibility allocation, and predictable institutional safeguards.

This difference is not rooted in varying levels of technical understanding, but in differing sources of institutional trust. In finance and payments, this distinction is especially pronounced, as relevant technologies directly involve asset security, legal liability, and public governance. The adoption threshold is determined not by "ease of use," but by "who is responsible when things go wrong, how liability is enforced, and whether remedies exist."

2.2 Institutional Standards for Public Monetary Arrangements

In monetary and payment system research, the BIS has proposed a core set of standards for assessing whether a form of money can perform broad payment functions. In its research on the future of monetary systems and annual economic reports, the BIS summarizes qualified public monetary arrangements into three interrelated institutional dimensions:

The first is singleness of money, requiring different forms of money to maintain one-to-one equivalence in payment and settlement, without systemic discounting based on issuer or carrier;

The second is elasticity, requiring the money supply to have the capacity to adjust under stress to prevent payment system failure due to liquidity shortages;

The third is integrity, requiring the monetary system to effectively integrate anti-money laundering, sanctions enforcement, consumer protection, and other governance mechanisms.

This framework is not tied to any specific technological path, but stems from institutional summaries of long-term experiences in modern monetary systems. Its value lies not in judging "which technology is more advanced," but in indicating "which arrangement is more likely to be institutionally absorbed."

2.3 Institutional Definition of the Stablecoin "Chasm"

In this study, "stablecoins crossing the chasm" is defined as the following institutional transformation: stablecoins shift from being technical value carriers primarily serving native crypto users to becoming payment and settlement arrangements that can be institutionally trusted, legally accountable, and scalable within existing financial and payment systems for broader economic actors.

The key to this transformation is not transaction speed or cost advantage, but whether stablecoins can approach or meet the minimum requirements of public monetary arrangements across the three institutional dimensions of singleness, elasticity, and integrity. In other words, true "crossing" is not about going from niche to mass users, but from "self-borne responsibility" to "institutionally absorbable responsibility."

Chapter Three The Early Stablecoin Market

3.1 Functional Status of Stablecoins in the Crypto Ecosystem

Within the crypto economy, stablecoins have established a clear and solid foundational status, extending far beyond being "a class of low-volatility assets" to becoming the de facto unit of account, settlement, and liquidity base for the entire system. From an on-chain structural and behavioral standpoint, this status is not derived from price performance or market cap rankings, but directly reflected in issuance scale, usage intensity, and functional positioning.

In terms of存量 size, according to comprehensive data from on-chain platforms like DeFiLlama and industry statistics, the global circulating supply of stablecoins showed a clear structural expansion trend between 2023 and 2025: starting at around $120 billion in early 2023, after a temporary pullback post-2022 industry deleveraging, it rebounded in 2024 and stabilized around $230 billion by late 2024 to mid-2025, reaching $250–300 billion under some measurement standards. This indicates that stablecoins are no longer short-term tools fluctuating with market sentiment, but have developed a structural存量 above historical averages, with sustained presence.

In decentralized finance (DeFi), the foundational role of stablecoins is particularly evident. According to DeFiLlama's metrics, stablecoins consistently accounted for 30%–50% of total value locked (TVL) in DeFi protocols between 2023 and 2025, serving as primary units of account and settlement in core modules such as lending, decentralized exchanges, liquidations, and yield distribution. In many major DeFi protocols, stablecoins serve both as key collateral on the asset side and as benchmark units on the liability and liquidation sides, with turnover frequency and settlement counts significantly exceeding most non-stablecoin crypto assets.

At a broader on-chain usage level, the "settlement layer" attribute of stablecoins becomes even clearer. According to Chainalysis' annual tracking of on-chain data from 2023 to 2024, the annual on-chain settlement volume of stablecoins has reached several trillions of dollars, far exceeding their nominal issuance规模. In terms of transfer amounts, stablecoin-related transfers accounted for 40%–60% of total on-chain transfer volumes in most years; in certain years and regional samples, their settlement规模 even surpassed single high-market-cap crypto assets like Bitcoin or Ethereum. This "high turnover, low holding" usage pattern clearly shows that stablecoins are primarily used as tools for payments, settlements, and cross-border transfers—not as long-held risky assets.

On centralized exchanges, this functional division similarly holds. Whether in spot or derivatives markets, stablecoins have become the dominant unit of account and settlement medium, playing a foundational role in connecting different crypto asset markets. In terms of market structure, the stablecoin segment exhibits high concentration: USD-denominated stablecoins account for over 90% of total stablecoin market cap, with USDT and USDC forming a long-standing "duopoly," collectively holding 80%–90% of the market share as of mid-2025. This concentration further strengthens the network effect of stablecoins as unified units of account and settlement.

Taken together, the role of stablecoins in the crypto ecosystem is not to bear price risk or generate excess returns, but to provide a stable settlement foundation for risky asset trading, leverage activities, and on-chain financial operations. In this sense, stablecoins have already attained a functional status akin to a "base monetary layer" in the crypto economy: while not risky assets themselves, they constitute the core infrastructure enabling the operation of risky asset markets.

3.2 Establishment of the Early Market and Its Limitations

Although stablecoins have formed mature and indispensable use cases within the crypto ecosystem, this success should be understood as the "establishment of an early market," not a technological or institutional "crossing of the chasm." The widespread use of stablecoins today does not imply they have transformed from niche technical tools into mainstream financial arrangements.

This assessment stems first from the structural characteristics of their usage prerequisites. At present, the primary users of stablecoins remain native crypto users, crypto exchanges, DeFi protocols, and some professional institutions. These entities generally possess strong technical understanding and tolerate high levels of on-chain operational risk, counterparty credit risk, and legal and regulatory uncertainty. In most use cases, risks are not institutionally transferred but borne individually or organizationally; whether stablecoins enjoy a clear legal status or have public-level redress mechanisms is rarely a core consideration in their adoption decisions.

Second, from a market structure perspective, the "mature use" of stablecoins relies on a highly centralized issuance system. Despite exhibiting strong decentralized usage features functionally, stablecoins are highly dependent on a few leading issuers in terms of issuance and governance. As previously noted, USD-denominated stablecoins dominate the market, with USDT and USDC forming a long-standing duopoly, collectively controlling 80%–90% of the market share. This means the stable operation of the stablecoin system heavily depends on the reserve management, redemption mechanisms, legal structures, and compliance capabilities of a few issuers.

This structure is acceptable in the early market phase. On one hand, a highly centralized issuance system strengthens network effects, enabling stablecoins to quickly become unified units of account and settlement; on the other hand, early users do not expect issuers to assume responsibilities akin to public financial institutions, nor do they require them to possess systemic risk resolution or macroeconomic stabilization functions. Yet it is precisely this structure—of "high functional importance with relatively limited institutional responsibility"—that keeps stablecoin success confined to the early adopter-dominated market stage.

This constitutes the key constraint when stablecoins attempt to expand into broader economic systems. Unlike native crypto markets, the decision logic of enterprises, financial institutions, and public sectors does not rest on "self-borne risk," but on institutional safeguards, legal accountability, and clear risk allocation mechanisms. For these actors, the efficiency of a settlement tool is not the sole criterion; more importantly, they need to know: if extreme situations arise, can risks be institutionally absorbed, are responsibilities clear, and are redress pathways enforceable?

Therefore, the success of stablecoins in the early market cannot be naturally extrapolated to their feasibility in broader economic systems. "Crossing the chasm" requires transforming a tool used by a few professionals under incomplete institutional conditions into a financial arrangement accepted by most economic actors within a clear institutional framework. This migration cannot be achieved simply by expanding usage规模, but inevitably involves deeper institutional restructuring and regulatory responses.

Chapter Four The Institutional Chasm of Stablecoins: Three Constraints of Public Monetary Arrangements

Whether stablecoins can move from native crypto markets to broader real economies depends not on whether they are faster, cheaper, or "technically superior" in specific scenarios. The real constraint arises from a more fundamental question: can they be regarded as payment and settlement arrangements that institutions can absorb within existing financial governance frameworks?

In this sense, the "chasm" faced by stablecoins does not occur at the level of user experience or market education, but stems from structural tensions with modern monetary institutions. To understand this tension, the discussion must shift from technical comparison to institutional benchmarks, placing stablecoins back into the analytical framework of international monetary and financial governance.

4.1 Analytical Framework: Institutional Benchmarks for Public Monetary Arrangements

In its research on the future of monetary systems, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) proposed a widely cited analytical framework to assess whether a form of money possesses the institutional conditions to perform broad payment and settlement functions. This framework does not focus on technological paths, but on three foundational institutional requirements: singleness of money, elasticity, and integrity.

The core value of this framework is shifting the discussion from "what technology can do" back to "what institutions must guarantee." Under this benchmark, the differences between stablecoins and central bank or commercial bank money are not performance-based, but stem from divergent institutional attributes.

4.2 The First Chasm: Singleness Constraint and the Challenge of Monetary Uniformity

In modern financial systems, the coexistence of different forms of money without systemic stratification is not due to spontaneous market arbitrage, but to institutional arrangements backed by public authorities. Commercial bank deposits, e-money, and cash are considered equivalent because they are all embedded in the same clearing system, with central banks providing a credit anchor as final settlement agents.

The European Central Bank has repeatedly emphasized in its research on "monetary uniformity" that the stable operation of payment systems depends on the public’s shared expectation that "one unit of currency always retains equal value." Once this expectation breaks down and structural discounts emerge between payment instruments, network effects weaken rapidly and could amplify financial risks through shifts in confidence.

In contrast, the current singleness of mainstream stablecoins relies primarily on market-based arrangements: the quality and liquidity of reserve assets, the issuer’s ability to fulfill redemption commitments, and market trust in the sustainability of these arrangements. Although some issuers enhance confidence through increased disclosure transparency, third-party reviews, or audits, from an institutional perspective, this remains a market-based mechanism of equivalence, not a publicly guaranteed one.

This difference may not be apparent under normal conditions, but becomes critical under stress. IMF financial stability analyses indicate that if markets develop doubts about reserve assets, custody structures, or legal arrangements, stablecoin prices may quickly deviate from their pegs, with their stability highly dependent on the continued validity of external conditions.

Therefore, in terms of singleness, stablecoins lack the same institutional safeguards as bank or central bank money, making their acceptability inherently conditional.

4.3 The Second Chasm: Elasticity Constraint and the Absence of Liquidity Support

Elasticity is a key institutional feature distinguishing modern monetary systems from commodity money or fully reserved money. Through central bank re-lending mechanisms, open market operations, and the lender-of-last-resort function, money supply can be adjusted during shocks to prevent payment system disruptions due to liquidity shortages.

The BIS has explicitly stated in multiple studies that payment system robustness does not require money to be fully asset-backed at every moment, but rather demands a credible source of liquidity support at critical junctures.

By design, most stablecoins adopt full or high-ratio asset-backing models, structurally resembling narrow banks or money market funds. While this limits credit expansion under normal conditions, it also creates clear institutional constraints: without central bank liquidity support or equivalent mechanisms, stablecoin systems facing concentrated redemptions or market shocks can only rely on the liquidity of reserve assets. If reserve assets face liquidity constraints, their stability is immediately tested.

The IMF has pointed out in its research on digital currencies that the lack of elastic support determines that stablecoins struggle to serve as macroeconomic stabilizers. They can supplement settlement tools, but are unlikely to become core components of the money supply system.

4.4 The Third Chasm: Integrity Constraint and Insufficient Governance Integration

Modern monetary systems are not just collections of payment tools, but deeply institutional networks embedded in national governance and international cooperation. Anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, sanctions enforcement, and consumer protection are not optional add-ons, but prerequisites for broad acceptance of money.

Both the BIS and IMF have emphasized in numerous studies that the integrity of monetary systems directly affects the legitimacy and sustainability of financial systems. A monetary form that cannot be effectively regulated, enforced, or clearly attributed legally—even if technically feasible—will struggle to gain institutional recognition.

Although some stablecoin issuers have made significant investments in compliance in recent years, overall, the stablecoin system still lags behind traditional finance in legal liability attribution, cross-border regulatory collaboration, and enforceability. Especially in cross-border usage scenarios, differing legal classifications and regulatory jurisdictions create fragmented and unpredictable governance structures.

In its analysis of cross-border payments and stablecoins, the IMF notes that insufficient governance integration is not a marginal issue, but one of the core institutional risks facing stablecoins—and a key factor regulators consider when assessing their systemic impact.

4.5 Summary: The Institutional Nature of the Chasm

Overall, the "chasm" faced by stablecoins does not stem from a single risk or isolated flaw, but from systemic gaps compared to public monetary arrangements across the three institutional dimensions of singleness, elasticity, and integrity. This gap does not deny the practical value of stablecoins in specific contexts, but clearly indicates that at this stage, they cannot yet be regarded as fully institutionalized, broadly absorbable monetary arrangements.

The future of stablecoins does not depend on continued technological progress, but on whether and to what extent they can gradually close these institutional gaps through institutional design and regulatory responses.

Chapter Five The Emergence of Institutional Bridges: Comparative Analysis of Stablecoin Regulatory Responses

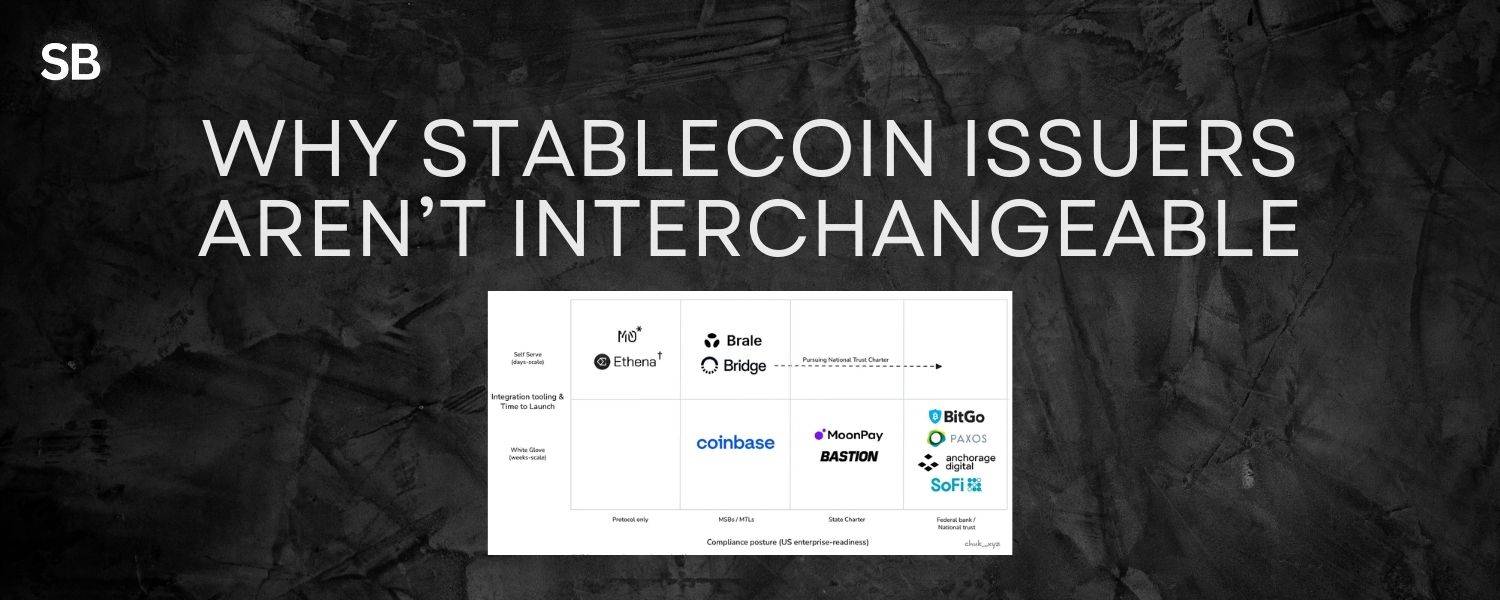

Chapter Four has shown that the challenges facing stablecoins are not singular risks, but a set of structural constraints rooted in modern monetary institutions. Against this backdrop, whether stablecoins can continue expanding their application boundaries depends less on issuers’ market strategies or technical capabilities, and increasingly on whether and how public authorities are willing to incorporate them into existing financial governance systems.

In the past two years, a key shift has occurred: major economies and international financial centers are moving from early risk warnings and principled statements toward enforceable regulatory and legislative arrangements. This shift does not mean stablecoins are being redefined as "safe innovations," but that regulators are beginning to tackle a more practical question: even if institutional gaps cannot be eliminated, can rules be designed to confine stablecoins within a controllable, accountable, and intervenable operational range?

It is precisely in this sense that these regulatory responses constitute "institutional bridges" emerging during stablecoins’ attempt to cross the chasm.

5.1 Overall Logic of Institutional Response: From Observation to "Conditional Inclusion"

From comparative legal and regulatory perspectives, while different jurisdictions vary significantly in institutional design, their underlying logic shows strong consistency.

First, stablecoins are no longer simply grouped into the broad category of "crypto assets," but are separately identified as special financial arrangements that may perform payment and settlement functions. This reclassification shifts regulatory focus from price volatility and investor protection to core issues of payment system safety and financial stability.

Second, regulatory focus has shifted upstream. Instead of mainly constraining exchanges and secondary markets, regulators now systematically regulate issuance, reserves, redemptions, and governance structures. Regulators now care less about "who is trading" and more about "who promises equivalence, who manages risk, and who bears responsibility in extreme scenarios."

More importantly, the framing of regulatory objectives has changed. Major jurisdictions do not aim to "eliminate all risks of stablecoins" through regulation, but seek to ensure their operations fall within a predictable, accountable, and interruptible governance range through institutional design.

It is precisely in this sense that the implicit premise of "institutional bridges" is not encouragement of expansion, but containment and fallback: the bridge is not built to make vehicles go faster, but to ensure that when accidents happen, we know who is responsible, how to brake, and whether the vehicle can be towed away.

5.2 EU Path: Comprehensive Rules Addressing Singleness and Integrity

Among major jurisdictions, the EU’s institutional response to stablecoins is the most systematic, exemplified by the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA). The core feature of this framework is not technology-driven, but institutionally layered.

MiCA does not apply a single standard to all stablecoins, but links regulatory intensity directly to institutional risk by distinguishing between "asset-referenced tokens" (ART) and "electronic money tokens" (EMT). The institutional implication is clear: whether a stablecoin poses a public risk depends on its pegging method, usage scale, and potential systemic importance—not on whether the blockchain is "decentralized."

On singleness, MiCA attempts to partially convert the market-based trust in stablecoin equivalence into enforceable institutional obligations by setting explicit requirements on reserve asset quality, composition ratios, custodial segregation, and disclosure frequency. Crucially, imposing higher capital, liquidity, and governance requirements on "significant" stablecoins reflects the EU’s sensitivity to monetary uniformity: once a stablecoin occupies a key position in the payment system, its stability ceases to be a private matter for the issuer.

Regarding integrity, MiCA systematically embeds anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, consumer protection, and cross-border regulatory cooperation into the regulatory framework, enhancing enforceability through EU-level coordination. Its goal is not to drive large-scale expansion of stablecoins, but to prevent regulatory arbitrage in areas of blurred institutional boundaries.

5.3 U.S. Path: Redefining Functional Boundaries Around USD Stablecoins

Unlike the EU’s systematic legislation, the U.S. institutional response to stablecoins is more function-oriented and incremental. In U.S. policy discussions, stablecoins are almost always examined within the context of the U.S. dollar payment system and the international role of the dollar.

The core regulatory question in the U.S. is not whether stablecoins "resemble securities," but whether, if widely used for payments, their risks have approached those of bank money or other regulated payment instruments. This question directly determines the intensity and manner of regulatory intervention.

In institutional design, the U.S. does not attempt to solve the elasticity issue through stablecoins themselves, but tends to indirectly compress systemic risk space by restricting issuer types, strengthening reserve asset safety, and emphasizing connections to the banking system. This implies that in the U.S. context, stablecoins are positioned as payment-layer innovations embedded within the existing U.S. dollar financial system, not as independent money supply mechanisms—their macro-regulatory functions remain with the central bank and banking system.

Notably, U.S. stablecoin regulation still exhibits characteristics of multi-agency parallel oversight and intertwined legislative-regulatory debates. While this uncertainty increases compliance costs in the short term, it also reflects another facet of the U.S. institutional path: preserving room for institutional evolution without rushing to final answers.

5.4 Hong Kong Path: An "Experimental Bridge" Centered on Issuer Responsibility

Within Chinese-speaking financial systems, Hong Kong’s stablecoin regulatory path holds special significance. Its uniqueness lies not in being permissive or aggressive, but in its intense focus on issuer responsibility as an institutional anchor.

Hong Kong regulators have clearly defined stablecoin issuance as a regulated activity, using a licensing system to concentrate reserve management, redemption mechanisms, corporate governance, and risk control at the issuer level. The institutional meaning is clear: the institutional credibility of stablecoins depends first on whether there exists a regulatable, accountable, and legally lockable center of responsibility.

By incorporating issuers into anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, and financial regulatory systems, the Hong Kong approach directly addresses integrity concerns, helping alleviate regulators’ worries about "governance vacuums." At a macro level, the Hong Kong model is less about rapid expansion and more like an institutional experiment—observing under strict regulatory conditions the real-world performance of stablecoins in payments, settlements, and cross-border scenarios to provide verifiable experience for future policy choices.

5.5 Comparative Analysis: Effectiveness and Limits of Institutional Bridges

Comparing the three paths reveals that major jurisdictions are not attempting to eliminate all institutional gaps of stablecoins at once, but prioritizing repairs on the most pressing risk dimensions.

The EU focuses on singleness and integrity, the U.S. emphasizes functional boundaries with existing monetary systems, and Hong Kong strengthens governance integration through issuer responsibility. These institutional designs are building several limited-load-bearing bridges, allowing stablecoins to enter certain real-world scenarios under controlled conditions.

However, it must be stressed that these bridges do not signify "completed crossing." Their effectiveness heavily depends on enforcement strength, market feedback, and cross-border regulatory coordination. If usage scale, functional spillovers, or risk exposure exceed expectations, these institutional bridges themselves may be rapidly reinforced, restricted, or even dismantled.

Thus, Chapter Five does not reveal a process of stablecoins being "accepted," but how they are conditionally tolerated under institutional vigilance. This is precisely the premise for understanding the "scenario-first" approach in Chapter Six: the space available for stablecoins is not determined by technology, but incrementally conceded by institutional tolerance.

Chapter Six Bowling Pin Scenarios: Practical Paths for Stablecoins to Cross the Chasm

In the analytical framework of *Crossing the Chasm*, a frequently overlooked yet highly explanatory insight is that technologies that truly complete the crossing almost never do so through "full-scale rollout." Instead, they typically first break through in a few highly focused scenarios—knocking down the most resistant nodes—then gradually diffuse along adjacent needs.

This strategy is vividly termed the "bowling pin path": not trying to knock down the entire row at once, but first hitting the lane most likely to trigger chain reactions.

Applying this methodology to stablecoins necessitates a shift in focus. The question is no longer "do stablecoins generally meet the institutional requirements of public monetary arrangements," but: under the premise that institutional constraints are not yet fully lifted, which specific scenarios already show conditions for "preliminary crossing"—institutionally tolerable, risk-absorbable, and value-verifiable.

6.1 Realistic Criteria for Scenario Screening

In stages of incomplete institutional maturity, whether stablecoins get adopted often depends not on theoretical "efficiency," but on whether three more practical conditions simultaneously hold.

First, friction costs in the existing system must be sufficiently high. Only when traditional paths impose clear constraints on business activities through cost, speed, or accessibility will stablecoins’ efficiency advantages outweigh their institutional uncertainties.

Second, risks must be borne primarily by professional entities. If risks can be confined within enterprises, financial institutions, or other entities capable of identifying and absorbing them, regulators’ concerns about institutional spillovers are significantly reduced.

Third, there must be clear responsibility and compliance interfaces. Even without full institutional alignment, as long as responsible parties are identifiable and accountable, and compliance obligations can be embedded into existing regulatory processes, stablecoins may gain limited space.

Based on these criteria, the "practically viable scenarios" repeatedly mentioned by international organizations and regulators over the past year mainly cluster in three categories.

6.2 Cross-Border B2B Settlement: Instrumental Embedding in High-Friction Environments

Among all application scenarios, cross-border B2B settlement is considered one of the most practically breakthrough-prone areas for stablecoins—not due to technological novelty, but because of the long-standing structural frictions in traditional cross-border payment systems.

According to joint World Bank and BIS research on cross-border payments in 2024–2025, traditional cross-border B2B payments still face long settlement cycles (2–5 business days), multiple intermediary layers, and opaque fees in most corridors—especially pronounced in emerging markets and SME trade. These frictions provide real entry points for non-bank settlement tools.

In this scenario, stablecoins do not appear as "currency replacements," but are embedded more as optimized components of settlement paths. Regarding singleness, trading parties do not demand long-term, unconditional value stability from stablecoins, but only require they maintain their peg during contract fulfillment periods. This "transaction-unit-based" assessment of equivalence fundamentally differs from retail payments or public holding, where monetary uniformity is essential.

On elasticity, cross-border B2B settlement deliberately avoids macro monetary supply issues. Stablecoin usage scale is determined by specific trade activities, not by countercyclical adjustments or liquidity backstops. Their supply elasticity is compressed within commercial logic, reducing institutional demands for public liquidity support.

On integrity, the governance foundation here is relatively clear. Participants are typically regulated enterprises or financial intermediaries, with explicit transaction backgrounds and pre-allocated AML, sanctions screening, and compliance responsibilities. Stablecoins do not form independent payment networks outside existing rules, but are embedded within current compliance processes.

It is precisely under these highly constrained conditions that stablecoins exhibit a "low institutional friction" usability in cross-border B2B settlement. This does not mean they have crossed all institutional chasms, but indicates that in specific commercial structures, some chasms can be temporarily bypassed.

6.3 Corporate Treasury Management and Inter-Institutional Settlement: De-Publicized Institutional Buffer Zones

Compared to cross-border trade, stablecoin use in corporate treasury management and inter-institutional settlement further weakens their "monetary attributes."

In these scenarios, stablecoins often serve within enterprise groups, long-term cooperating institutions, or specific financial infrastructure nodes—functioning more like internal or semi-internal settlement tools. According to IMF and multiple central banks’ 2024 research on digital settlement tools, enterprise-level applications prioritize "controllability, reconcilability, and auditability" over whether the tool is legal tender.

Such closed or semi-closed environments allow equivalence assessments of stablecoins to be integrated into corporate financial controls and risk management systems, without relying on public credit backing. Here, stablecoins resemble a choice of settlement technology, not a choice of monetary form.

On elasticity, such applications also deliberately avoid macro roles. Enterprises use stablecoins to improve fund transfer efficiency and extend settlement windows, not for credit expansion or asset allocation. Thus, their supply mechanisms are naturally "de-macroized," no longer touching central bank-level liquidity responsibilities.

On integrity, enterprise-level scenarios actually possess stronger institutional embedding capabilities. Relevant transactions are typically already under audit, tax, and regulatory reporting obligations. Introducing stablecoins doesn't create new anonymity spaces, but only changes settlement carriers. This allows regulators to focus on issuer qualifications, reserve safety, and custody structures, rather than the transaction network itself.

Therefore, the "feasibility" of this scenario does not stem from resolving institutional chasms, but from effectively shrinking them into a manageable scope.

6.4 Dollarization Demand in Emerging Markets: Detouring Rather Than Crossing

Stablecoin usage in emerging markets follows a completely different logic. According to Chainalysis’ 2024–2025 Global Crypto Adoption Report, in some high-inflation, capital-controlled, or financially underdeveloped economies, stablecoins are widely used for value storage and cross-border transfers, functioning in practice as "informal dollarization tools."

This phenomenon is not a result of institutional design, but a market response to domestic currency instability and restricted payment channels. Regarding singleness, users prioritize relative stability over institutional guarantees; regarding elasticity, stablecoins serve private hedging functions; on integrity, this scenario precisely exposes insufficient governance integration and is the form most concerning to regulators.

Thus, this scenario is more accurately described as "detouring around" the institutional chasm, not genuinely "crossing" it. It heightens the policy urgency of stablecoin issues but does not constitute a path that regulatory systems can actively replicate or endorse.

6.5 Why Retail Payments Are Not a Priority Breakthrough?

Counterintuitively, retail payments targeting ordinary consumers are precisely where stablecoins lack preliminary crossing conditions.

First, in terms of efficiency benchmarks, retail payments are among the lowest-friction domains in today’s financial system. BIS and World Bank 2024 payment system studies note that in major economies, retail payments are highly digitized, with near-real-time payment systems widely available, low failure rates, and nearly zero end-user costs. In China, the EU, and parts of emerging markets, retail payment settlement speeds are close to instant, offering minimal marginal efficiency gains for stablecoins in local retail settings.

Second, from an institutional standpoint, retail payments impose the highest demands on singleness, consumer protection, and redress mechanisms. The IMF and BIS have explicitly stated in multiple joint studies that once a payment tool targets the general public, its regulatory standards quickly align with bank deposits or e-money. This means stablecoins in retail payments would need to assume nearly full public monetary arrangement responsibilities—the very aspect they currently struggle to meet.

Third, usage patterns show stablecoins are not concentrated in retail consumption. Chainalysis’ 2024 classification of on-chain transactions shows stablecoins are primarily used for cross-border transfers, exchange settlements, DeFi interactions, and inter-institutional fund transfers, with daily consumer payments remaining a small share.

More importantly, retail payment scenarios directly expose ordinary consumers to risk. Regulators must anticipate worst-case scenarios and ensure clear redress paths when issuers fail or systems malfunction. This risk-bearing structure makes retail payments the scenario with the lowest institutional tolerance.

6.6 Summary: Scenario-First, Not System Replacement

Combining the above analysis, stablecoin expansion in the real world is not advancing along the traditional path of "first becoming a qualified currency, then entering the payment system." Instead, their actual evolution involves first being used as tools in several high-friction scenarios, then accepting institutional constraints through use.

Cross-border B2B settlement and corporate treasury management have become early落地 scenarios not because these fields have lower institutional demands, but because risks can be compressed among a few professional entities, responsibilities can be pre-allocated via contracts and compliance structures, and failure costs do not directly spill over to the public. Under these conditions, stablecoins can demonstrate real value in settlement efficiency and accessibility without assuming full public monetary functions.

In stark contrast, retail payment scenarios面向the public. Here, singleness, elasticity, and integrity are not requirements that can be "temporarily suspended," but prerequisites for whether a payment tool can be permitted at all. Precisely for this reason, retail payments have not become stablecoins’ first breakthrough direction, but instead represent the domain with the clearest institutional boundaries and lowest regulatory tolerance.

This contrast reveals the true nature of stablecoin expansion: it is not achieving growth by fully meeting institutional standards for public monetary arrangements, but through gradual, limited, and highly conditional evolution along a few high-friction, highly specialized, and risk-containable application scenarios. Stablecoins are not "replacing systems," but being used in a limited way within the cracks allowed by the system.

It is precisely in this sense that whether stablecoins "cross the chasm" has never been a binary question, but depends on: in which scenarios institutions are willing to take a step back, while risks remain controllable.

Chapter Seven After Crossing the Chasm: Structural Impact of Stablecoins on the Financial System

If the previous analysis discusses "whether stablecoins have the conditions to cross the chasm," this chapter focuses on a more institutionally significant question: once stablecoins achieve institutional embedding in several key scenarios, how will they alter the structural operation of the financial system—not merely adding a new technical option?

It must be emphasized that this chapter does not discuss the wholesale replacement of existing systems by stablecoins, but examines a series of non-trivial structural adjustments triggered by stablecoins entering certain settlement and fund flow segments in a limited, backend, and instrumental manner, based on the realistic paths identified earlier.

7.1 Changes in Payment and Clearing Structures: Technical Decoupling of the Settlement Layer from the Account System

In traditional financial systems, account systems and payment clearing are highly coupled: accounts serve as both identity carriers and the basis for clearing and final settlement. This structure ensures governability while defining payment efficiency and operational boundaries.

The embedding of stablecoins in scenarios like cross-border B2B settlement and inter-institutional fund transfers is the first time this coupling relationship has been systematically loosened at the technical level. The key is not "whether blockchain is used," but that settlement functions are beginning to be separated into an independently optimizable technical layer: account relationships remain within the banking system, but some clearing and settlement paths can now be completed without relying on bank operating hours or passing through multiple correspondent banks.

The substantive impact of this change is that the payment system begins to exhibit a layered structure of "account layer–settlement layer–compliance layer." The account layer continues to handle identity verification and asset custody, the compliance layer continues to embed regulatory and risk control requirements, while the settlement layer gains space for technical upgrades and outsourcing in specific scenarios. Stablecoins do not negate the account system, but are reshaping the technical implementation of the settlement layer.

7.2 Reorientation of Banks’ Roles: From "Payment Channel" to "Institutional Interface Node"

In early stablecoin narratives, banks were often seen as intermediaries to be bypassed. But in institutionalized application scenarios, stablecoins do not diminish bank importance—they change how banks are needed.

As stablecoins enter regulated frameworks, their operation heavily relies on several core banking functions: reserve asset custody, fiat on/off ramps, audit cooperation, and compliance and sanctions interfaces. This means a bank’s value is no longer primarily in "controlling payment paths," but in whether it can serve as a trustworthy interface between institutions and technology.

The deeper implication is that banks are shifting from "payment executors" to "providers of institutional assurance." In stablecoin-related structures, banks are no longer mandatory conduits for every transaction, but remain key anchors for the system’s legitimacy, accountability, and intervenability. This shift does not weaken the banking system, but reaffirms its irreplaceability in financial governance.

7.3 Real Impact on Monetary Sovereignty: From "Replacement" to "Usage Patterns"

The impact of stablecoins on monetary sovereignty is often misinterpreted as "replacing domestic currency." But in practice, the more institutionally significant change is not replacement, but structural shifts in settlement currency choices.

With USD-denominated stablecoins dominating, their use in cross-border settlements, institutional treasury management, and emerging markets objectively reinforces the U.S. dollar’s settlement role in digital environments. This reinforcement is not achieved through official policy, but through market choices driven by efficiency, accessibility, and settlement certainty.

The outcome is not a "parallel monetary system," but a shift in participants’ expectations about the "default settlement currency" in specific scenarios. Hence, major economies’ concerns about stablecoins are not about challenging domestic currency’s legal status, but about forming irreversible path dependencies in critical settlement links.

7.4 Changes from a Financial Stability Perspective: Risk Is Not Eliminated, But Reallocated

The institutional embedding of stablecoins does not eliminate financial risk, but redistributes its location and form.

In the native crypto phase, risks mainly manifested as price volatility, technical failures, and individual project collapses; in the institutionalized phase, risks concentrate more on issuance structures, governance arrangements, and infrastructure nodes. The highly concentrated stablecoin issuance landscape means a few entities may attain systemic importance at the settlement level, whose reserve mismanagement, compliance lapses, or legal disputes could rapidly amplify impacts through settlement networks.

Thus, the key challenge posed by stablecoins is not "whether they are dangerous," but whether risks are identified, whether clear responsible parties exist, and whether institutional intervention tools are available. This is precisely why regulatory focus has shifted from user behavior to issuers and infrastructure layers.

7.5 Long-Term Impact on the Web3 Industry: Compliance Capability Replaces Narrative Power

After stablecoins gradually enter real economic scenarios, their impact on the Web3 industry itself is not about technical route competition, but a fundamental shift in project success logic.

In the native crypto phase, whether a Web3 project could grow depended on three things: how novel the technical concept was, how strong the token incentives were, and how fast market expansion occurred. At that stage, projects were rarely asked "legal responsibility," "regulatory compliance," or "who bears the cost in extreme cases," because their primary users inherently had high risk tolerance.

But once stablecoins are used for cross-border settlements, corporate treasury management, or other real business scenarios, this logic no longer holds. Real-world participants don’t care whether a project has a "complete decentralization narrative," but care deeply about very concrete questions: who legally owns the funds, who holds the reserves, whether liability can be pursued in disputes, and whether clear interfaces exist for regulatory intervention.

This means the core competitiveness of Web3 projects is shifting from "ability to attract liquidity" to "ability to be institutionally absorbed." Compliance design, governance structure, audit mechanisms, and communication capability with regulators are becoming prerequisite conditions for entering real-world application scenarios.

From this perspective, the development path of stablecoins shows that Web3 is not moving toward full de-institutionalization, but is gradually coupling with existing financial governance systems in key areas involving payments, settlements, and infrastructure. This trend is driving clear industry divergence: some projects remain in high-volatility, high-risk experimental fields; others proactively reshape their positioning around compliance, custody, and responsibility structures, aiming to become usable components in real financial systems.

7.6 Summary: Stablecoins Bring Not Revolution, But Restructuring of Financial Architecture

Overall, after crossing part of the institutional chasm, stablecoins’ impact on the financial system resembles more a structural rearrangement than a systemic disruption. The technical decoupling of the settlement layer, the repositioning of banks, subtle shifts in settlement currency choices, and the migration of risk governance focus together constitute the core of this adjustment.

These changes do not necessarily undermine the stability of existing financial systems, but require regulators, financial institutions, and market participants to rethink the relationships among "money," "payments," and "infrastructure." It is precisely in this sense that the structural impacts revealed in Chapter Seven form a key prerequisite for understanding stablecoin issues in the Chinese context discussed in Chapter Eight.

Chapter Eight Stablecoins in the Chinese Context: Institutional Boundaries, Compliance Paths, and Realistic Possibilities

When the discussion about whether stablecoins can "cross the chasm" enters the Chinese context, the analytical method itself must change. In this institutional environment, the key issue is not whether the technology is mature, whether scenarios exist, or whether market demand is present, but whether such arrangements could possibly be incorporated into the existing monetary and financial governance structure.

Therefore, for China, the stablecoin issue is not a choice question of "whether to embrace innovation," but a systemic question of how to handle exogenous financial variables. Only under this premise does the discussion gain practical relevance.

8.1 Institutional Premises of China’s Monetary and Financial Governance

In China’s financial governance system, money and payments are not neutral infrastructures, but core institutional tools deeply embedded in macroeconomic control, financial stability, and state governance goals. The legal status of the RMB as the sole legal tender, the gradual opening of capital accounts under overall controllability, and the service function of the payment system to anti-money laundering, anti-terrorism financing, and risk prevention goals constitute the basic constraints of this system.

Under such an institutional structure, any arrangement with "quasi-money" or "broad payment tool" characteristics, once it potentially bypasses the bank account system, weakens capital flow management, or forms de facto value storage substitution, will be placed under highly cautious regulatory scrutiny. This is not an attitude toward specific technological paths, but stems from the institutional positioning of the monetary system in the Chinese context.

Therefore, the discussion of stablecoins in China is naturally not about technology diffusion, but about institutional compatibility.

8.2 Institutional Boundaries of Stablecoins in the Mainland Context

Within the current institutional framework, it can be clearly stated: if stablecoins attempt to enter the mainland market as public-facing payment tools, units of account, or value storage media, their institutional space is extremely limited.

Functionally, foreign-currency or asset-pegged stablecoins, if widely used for settlement or holding, may create substitution effects for legal tender in localized scenarios; structurally, their cross-border liquidity characteristics may also weaken existing foreign exchange management and capital account control mechanisms. This combination of functional and structural factors makes it difficult to view stablecoins as "neutral technological tools."

Therefore, stablecoins lack the institutional conditions to exist as universal payment tools or publicly held asset forms in mainland China. This conclusion is not a value judgment, but a direct derivation from the logic of current monetary and financial governance.

8.3 Beyond "Impossibility": Where Meaningful Discussion Lies

However, clarifying institutional boundaries does not mean denying all meaningful discussion. On the contrary, only after "impossibility" is clearly defined do the remaining worthwhile questions become visible.

The fundamental reason stablecoins provoke institutional tension in the Chinese context is their potential monetary and payment functions. Therefore, when these functions are intentionally stripped away, their institutional meaning also changes. The real space for discussion is not about the possibility of stablecoins as "currency," but whether they can still exist as technical settlement or reconciliation arrangements after being de-monetaryized, de-publicized, and de-anonymized.

For example, in cross-border trade or international business, if stablecoins are used solely as settlement media within overseas compliant systems, not directly面向domestic public, and not serving as substitutes for domestic currency, their institutional nature fundamentally changes. In such cases, the discussion shifts from monetary sovereignty or payment security to how to understand and manage the existence of an external financial infrastructure.

8.4 The Hong Kong Path: A System Interface Rather Than a Demonstration Model

Against this backdrop, Hong Kong’s institutional practice on stablecoins is often symbolically overvalued externally. But from a more cautious perspective, the value of the Hong Kong path lies not in whether it can be replicated on the mainland, but in whether it can serve as a high-transparency institutional interface.

By clearly incorporating stablecoin issuance into a licensed regulatory framework, regulating issuers, reserve assets, custody arrangements, and redemption obligations, Hong Kong is not answering "whether stablecoins have prospects," but "if stablecoins already exist, can they be placed into a regulatable, accountable, and intervenable institutional container?"

Given Hong Kong operates under capital account free flow, common law jurisdiction, and a highly internationalized financial market, its regulatory assumptions differ significantly from the mainland. Therefore, Hong Kong’s more reasonable role is as an external observation sample, not as a pilot for mainland policy. By observing the real operation of stablecoins under Hong Kong’s institutional framework, mainland regulators and market participants can better assess their risk profiles, use cases, and regulatory costs without presupposing institutional transplantation.

8.5 Institutional Division Between Stablecoins and Digital RMB

Discussing stablecoins in the Chinese context, digital RMB is always an unavoidable institutional background variable. But viewing them simply as "competition between different technological paths" is itself a misreading of reality. What truly needs comparison is not underlying technology or user experience, but whether their served governance goals and institutional roles operate at the same level.

Digital RMB, from its inception, is highly endogenous to China’s existing monetary and financial governance system. Its institutional goal is not to create a new form of money, but to consolidate the legal tender status digitally, optimize payment infrastructure, and enhance the enforceability of monetary policy, anti-money laundering, and financial regulation in digital environments. In other words, digital RMB is an institutional tool serving the stable operation of the existing monetary system—its core value lies not in "being more convenient," but in "being more controllable, more regulatable, and more embeddable into governance goals."

Stablecoins, in contrast, have entirely different institutional starting points and evolutionary logic. Regardless of technological implementation, their core applications revolve around cross-border payments, international settlements, and digital asset ecosystems, aiming to reduce cross-jurisdictional settlement frictions and bypass efficiency bottlenecks of traditional correspondent banking networks. This functional orientation gives stablecoins inherent exogeneity: they do

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News