The Past of Huwang in Phnom Penh: "Cambodia's Alipay" Died Last Night

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Past of Huwang in Phnom Penh: "Cambodia's Alipay" Died Last Night

The shutdown of Huiwang is not merely the sudden death of a single company, but also marks the end of a distorted business era.

By: Sleepy.txt

December 1, 2025, Phnom Penh.

The wind by the Mekong remains humid and hot, but for the hundreds of thousands of overseas Chinese living here, this winter is far colder than any before.

This day will be etched into the collective memory of Cambodian Chinese entrepreneurs.

In the early morning on Sihanouk Boulevard, the headquarters building of Huiwang—once seen as a financial totem that "never sleeps"—suddenly lost its heartbeat overnight. The roar of armored vehicles coming and going had vanished. In its place was a cold notice titled "Suspension of Withdrawals" pasted on the glass door, and hundreds of increasingly rigid Asian faces standing in front of it, frozen with fear.

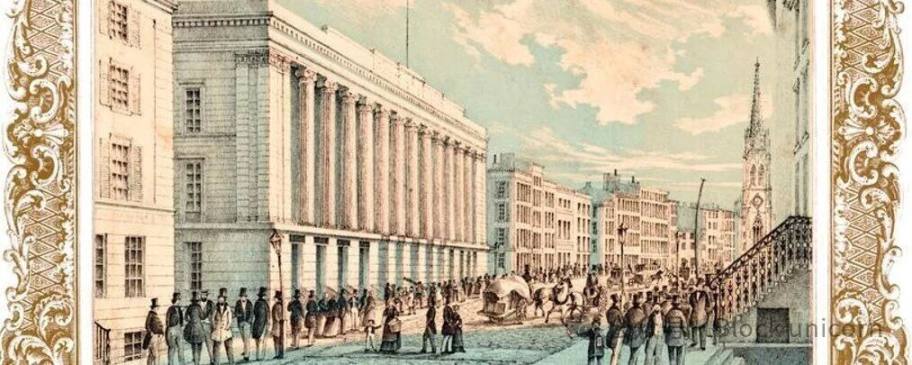

History always rhymes. This scene felt like being thrown back to Shanghai's Bund on the eve of the gold yuan collapse in 1948, or Beijing’s Financial Street during the P2P explosion wave in 2018.

The collapse didn’t come without warning. In the previous 48 days, rumors about the fall of this so-called "Alipay of Cambodia," a financial giant, had already spread like plague through underground money changers and Telegram groups in Phnom Penh. From joint U.S.-UK sanctions against Prince Group, to the seizure of $15 billion in crypto assets, to Huiwang's stablecoin USDH halving in value on the black market—every signal pointed to one outcome: liquidity dried up.

Huiwang’s shutdown wasn’t just the sudden death of a company; it marked the end of a distorted commercial era.

Over the past turbulent six years, it had been the central capillary of Cambodia’s underground economy. It connected casinos in Phnom Penh, industrial parks in Sihanoukville, and even scam operations across the Pacific, forming an offshore financial island seemingly impervious to the SWIFT system.

Its fall locked away the life savings of tens of thousands of Chinese entrepreneurs, and declared the complete bankruptcy of the "wild west logic."

The fantasy—that technological advantages could defy rules, that hiding in the jungle could avoid the hunter’s gun—had finally crashed headfirst into the iron wall of geopolitics and regulatory compliance.

This was a long-overdue reckoning, and a bloody, dark rite of passage that China’s generation of rogue internet expatriates had to endure.

The Lost Paradise of Tech Elites

If we retrace Huiwang’s rise, we find its origin not in evil, but in an extreme worship of efficiency.

Rewind to 2019. That year, China’s internet traffic红利 (dividend) peaked, triggering fierce competition over existing users. "Going global" became the grand narrative for big tech elites seeking new frontiers. A group of mid-level engineers and product managers from major Chinese tech firms landed at Phnom Penh airport, armed with cutting-edge code architectures and visions of inclusive finance.

Cambodia at the time was still stuck in the Jurassic age of finance.

Bank branches were scarce, services inefficient, foreign exchange controls strict. For hundreds of thousands of Chinese entrepreneurs in Phnom Penh working in trade, food service, and construction, moving money was a nightmare. They either risked carrying heavy stacks of dollar bills through the streets or suffered exorbitant fees from underground remittance networks.

To Chinese internet professionals accustomed to QR-code payments, this backwardness wasn’t just a pain point—it was a goldmine of untapped traffic and massive technological disparity.

Using mature Chinese mobile payment technology to launch a "dimensional strike" against Cambodia’s traditional finance became the unspoken mission of that generation of overseas pioneers.

And they succeeded brilliantly. From day one, Huiwang conquered the market with a "brutalist" level of convenience: fully Chinese interface, 24/7 customer support, instant transfers—it perfectly replicated Alipay’s smooth user experience.

But the real killer feature was its extremely low entry barrier. In a country where identity verification used to be rigorous, Huiwang required no complex KYC, no tax records—just a phone number, and money could flow freely through Phnom Penh’s underground network.

This strategy achieved massive commercial success. Within two short years, Huiwang penetrated every aspect of Chinese life in Phnom Penh—from buying milk tea to paying construction bills—becoming the de facto "Chinese central bank" in Cambodia.

Yet, technological neutrality is often the biggest lie in modern business.

As these "user experience first" product managers sprinted across Phnom Penh’s lawless terrain, they quickly encountered an unimaginable temptation in China: the tidal wave of black- and gray-market industries.

In the legitimate world, a payment platform’s core defense is risk control. But in Phnom Penh, the most profitable clients were gambling syndicates and telecom fraud compounds, whose greatest need was precisely "no risk control."

For these giants, transaction fees didn’t matter. What mattered was anonymity and security. They didn’t need a compliant e-wallet—they needed an underground river capable of instantly laundering hundreds of millions in illicit funds.

This was a classic ethical dilemma: when growth KPIs clash directly with compliance boundaries, who should technology bow to?

Huiwang bowed to growth.

They began using internet thinking to "optimize" money laundering processes. To retain these top-tier clients, they proactively removed facial recognition, relaxed transfer limits. In their logic, this was still "serving users" and "solving pain points." They hypnotized themselves with "technology bears no guilt," believing they were merely building roads—regardless of whether trucks carried goods or stolen cash.

It was this distortion of "technological instrumental rationality" that turned Huiwang from a convenient payment tool into Southeast Asia’s largest money laundering hub.

They thought they were Phnom Penh’s Jack Ma, changing commerce with technology. Unaware, in a jungle without rules, they had become the Du Yuesheng of the Mekong.

But this was only the beginning of their descent. Once the payment channel was open, these clever minds discovered another even more lucrative and darker path: applying "escrow e-commerce transactions" to human trafficking chains.

The SKU of Evil

In every internet business textbook, the "platform model" is seen as the ultimate evolution of commerce. After Huiwang secured payment infrastructure, its ambition naturally extended to the transaction layer.

In Phnom Penh’s jungle filled with fraud and violence, the scarcest resource wasn’t dollars or bodies—it was "trust."

This was a classic dark forest: snakeheads took money but didn’t deliver people, compounds accepted victims but refused payment, money launderers ran off with funds. High risks of betrayal severely hampered black-market transaction efficiency.

To these product managers, this wasn’t evil—it was a perfect "trust mechanism optimization scenario."

In 2021, "Huiwang Escrow" emerged out of nowhere.

Its product logic was a flawless replica of Taobao: buyers (fraud compounds) deposited funds into escrow, sellers (human traffickers) delivered, buyers confirmed receipt, then the platform released funds and took a commission.

This mechanism, designed in Hangzhou to help consumers confidently buy dresses, was now used in Sihanoukville to trade "front-end developers."

Inside Huiwang Escrow’s thousands of active Telegram groups, humans were completely reduced to cold, lifeless SKUs.

Every supply-demand post was meticulously standardized, resembling Double Eleven product pages:

"Proficient in Java, two years at a major tech firm, obedient, passport ready, price: 20K U."

"Wanted: Western market promotion team, self-sourced, price negotiable, escrow supported."

To technicians sitting in air-conditioned rooms maintaining the system, these were just lines of code and data. They didn’t see how those labeled "cargo" were stuffed into vans, nor hear the screams under electric batons. They only cared about backend order concurrency and rising GMV.

According to blockchain analytics firm Elliptic, since 2021, this platform has facilitated at least $24 billion in cryptocurrency transactions. This isn’t just a number—it’s the sum total of countless individual fates converted into betting chips.

Even more chilling was the rapid iteration of product features.

To meet compounds’ needs for capturing escapees, Huiwang Escrow even developed a "bounty" service.

In hidden groups, violence was no longer chaotic brutality, but a clearly priced, one-click add-on service: "Capture one escaped programmer: bounty 50K USDT; provide valid location: 10K USDT."

Such reckless expansion eventually drew the hunters’ gaze. In February 2025, under pressure from the U.S. FBI, Telegram shut down Huiwang Escrow’s main channel. This should have been devastating—but black-market resilience exceeded all expectations.

Just one week later, hundreds of thousands of users flooded seamlessly via backup links into another chat app called Potato Chat.

Telegram was known in circles as "Paper Plane"; Potato Chat, "Potato." Unlike planes flying in the sky, potatoes burrow deep underground—more concealed, harder for regulators to detect.

In this mass migration, Huiwang Group wasn’t just a facilitator, but the幕后 orchestrator. They didn’t just invest in "Potato" to relaunch their business under a new shell—they even developed their own standalone messaging app, ChatMe, attempting to build a fully closed, self-sustaining digital dark kingdom.

This "three-burrows-for-one-rabbit" guerrilla tactic wasn’t just mockery of regulation—it was profound arrogance.

They believed that if their code was fast enough, they could outrun the law; if servers were buried deep enough, they could create a lawless zone beyond reality. But they forgot: even darknet servers need electricity.

While they busied themselves changing disguises in the virtual world, in reality, an iron net targeting their funding chain was quietly tightening.

Symbiotic Model

In the game of finance, supreme power has never been about how many chips you hold, but about your ability to define the chips themselves.

Huiwang’s operators realized keenly that no matter how many shells they changed, as long as they relied on USDT, their throat remained in the hands of Americans across the ocean—because Tether could, at any moment, freeze on-chain assets at the FBI’s request.

So they decided to establish their own Federal Reserve on the banks of the Mekong.

In September 2024, Huiwang officially launched its stablecoin USDH.

In official promotional materials dripping with seduction, USDH’s core selling point was bluntly defined as "assets non-freezable" and "unbound by traditional regulations." This was effectively a rallying cry to the global underworld: Here, there is no FBI, no AML laws—this is an absolutely free financial utopia.

To promote this digital IOU issued by a private company, Huiwang rolled out a financial product that would make Wall Street blush: deposit USDH, earn 18% annual interest, 27% total return upon maturity.

Thus, an ironic scene unfolded. Scammers who spent their lives ruthlessly fleecing others, lured by this 18% yield, willingly funneled their hard-earned stolen cash back into Huiwang’s capital pool.

In Phnom Penh’s underground world, those cunning "pig-slaughtering scheme" bosses failed to realize that in front of Huiwang’s even larger pig-slaughtering scheme, they themselves had become the pigs awaiting slaughter.

Where did such audacity to "declare independence" come from?

If we examine Huiwang Pay’s board of directors, one prominent name stands out: Hun To.

What does this name mean in Cambodia? He is the nephew of former Prime Minister Hun Sen and cousin of current PM Hun Manet. According to U.S. Treasury sanction reports, this figure at the heart of Phnom Penh’s power structure wasn’t just a director of Huiwang—he was the umbilical cord connecting the company to Cambodia’s highest echelons of authority.

This is the darkest secret of Southeast Asia’s criminal ecosystem: symbiosis.

Chinese teams provided technology—using Big Tech’s code to build payment systems, e-commerce logic to manage human trafficking, blockchain to evade regulation; local elites provided privileges—supplying legitimate banking licenses, turning a blind eye to barbed-wire compounds, ensuring police ignored cries for help within.

Technology delivered efficiency; power ensured safety. Only under such high-level "protection" could they openly issue bounties, dare to launch private currencies challenging dollar dominance. To them, law wasn’t a red line—it was a commodity purchasable in bulk through bribes.

And this naked exchange of interests often wore the gentle mask of charity.

In Cambodian Chinese newspapers, you often saw images: Huiwang executives draped in sashes, receiving Red Cross honor certificates from dignitaries, donating vast sums to poor schools, smiling with benevolent grace.

At that very moment, inside Huiwang Escrow groups, blood-soaked money-laundering transactions were flashing疯狂ly on screens.

Morning: marketplace of evil. Afternoon: charitable gala dinner.

This extreme dissonance wasn’t hypocrisy—it was survival necessity. Just as Du Yuesheng once established his status as a "socially responsible elite" in Shanghai by founding schools and maintaining order, here on the Mekong, "charity" was a special tax paid to the power center—a bleach for identity, lubricant keeping this vast symbiotic machine running.

This carefully woven network of political-business ties gave Huiwang years of false security. They believed that as long as Phnom Penh connections held, they could dance along the edge of legality.

Until October 2025, when a butterfly flapped its wings across the ocean.

The sanction storm from Washington didn’t just topple their seemingly invincible umbrella—it shattered the fragile foundation of this "shadow central bank."

When Rogue Wisdom Meets the Financial Iron Curtain

In the traditional logic of China’s county-level economies, there are usually two ways to solve trouble: pull strings, or change disguises.

When crisis first loomed, Huiwang’s operators tried the old tricks again. Even after losing its banking license in March 2025, they naively released smoke screens by rebranding as "H-Pay" and announcing "expansion into Japan and Canada."

In their cognitive inertia, as long as the panda statue still stood in Phnom Penh, as long as the Hun Sen family still held shares, this was just another small problem solvable with money.

But this time, their opponents weren’t local cops taking bribes, but the fully armed American state apparatus.

On October 14, 2025, a massive black swan arrived. The U.S. Department of Justice announced the seizure of $15 billion in cryptocurrency linked to Chen Zhi of Prince Group.

This number suffocated the entire Southeast Asian underworld. Cambodia’s total GDP in 2024 was only around $46 billion. This wasn’t just asset confiscation—it was like draining a third of the country’s underground economy’s blood.

For Huiwang, Prince Group wasn’t just its biggest client—it was the source of its liquidity. Cut the source, and the downstream dies.

Even more terrifying was the nature of the attack.

For years, the underworld harbored an almost superstitious misunderstanding about USDT, believing it to be "decentralized" and immune to legal control. In reality, USDT is highly centralized. While the FBI can’t directly command Tether, as a company eager to integrate into mainstream finance, Tether must strictly comply with OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control) sanctions lists from the U.S. Treasury.

When U.S. regulators issued a long-arm jurisdiction order, no SWAT raids or lengthy cross-border lawsuits were needed—Tether’s backend simply froze the relevant addresses. Hundreds of millions in on-chain assets instantly became immovable "dead money."

This was a form of warfare they had never understood. These clever men, masters at exploiting loopholes, spent their lives drilling holes in walls. This time, the enemy tore down the load-bearing wall.

In the dust of the collapsing tower, it’s always the lowest ants who suffocate first.

At the end of Huiwang’s ecosystem thrived a vast group: currency exchangers. In Phnom Penh, they were motorcycle riders delivering physical dollars—the human armored trucks. In mainland China, they were gangs operating transfers from rental apartments. Earning a mere 0.3% spread, they bore the highest risk in the entire system.

Once, they were the most sensitive nerve endings of Huiwang’s machine. Now, they became the direct cannon fodder of card-blocking campaigns.

In Telegram’s "Frozen Friends Support Group," thousands of desperate pleas flood in daily—bank accounts frozen, names added to fraud penalty lists, unable to ride high-speed trains or fly, facing criminal prosecution upon returning home.

Once-lucrative delivery fleets are now high-risk prisons. They’re stuck holding unsellable USDH, domestic accounts frozen, stranded abroad.

A Generation’s Funeral

When the notice was posted on Huiwang’s headquarters glass door, what fell wasn’t just a company—it was an era.

This was a requiem for China’s internet "rogue globalization" era, a historical footnote to a period filled with delusions and ambitions.

During that specific window, a segment of overseas entrepreneurs charged into Southeast Asia’s jungle with a "spoiled child" mentality. They craved both the illegal profits and freedom of lawless zones, and the rules and safety of civilized worlds. They believed only in connections and technology, but never respected the law.

They thought technology was a neutral tool, unaware that tools in the hands of those without底线 (bottom lines) become weapons of crime. They imagined globalization was fleeing a cage into the wild, unaware it was merely stepping from one set of rules into another, stricter one.

Huiwang’s rise and fall is a modern parable of the "banality of evil."

At first, they only wanted to build a useful payment tool to solve currency exchange pain points. Then, for growth, they became accomplices to gray industries. Later, for profit, they became architects and participants in evil itself.

The moment someone decides to impose order on evil, they’ve already lost the way back.

Years later, when a new generation of overseas entrepreneurs sits in Phnom Penh’s sleek new office towers, sipping Starbucks and discussing ESG and compliant IPOs, perhaps no one will remember how many bytes of sin once flowed through the city’s underground cables.

Perhaps no one will remember how many self-proclaimed "Du Yueshengs" were buried beneath the Mekong’s night shadows.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News