Stablecoin Guide: What Are Stablecoins and How Do They Work?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Stablecoin Guide: What Are Stablecoins and How Do They Work?

This article introduces stablecoins and argues for the importance of stablecoin design.

Author: ARK Invest, Raye Hadi

Translation: Block unicorn

Introduction

This is the first of a four-part series designed to explain the complex mechanics of the stablecoin landscape. Stablecoin mechanisms are highly intricate, and there is currently no comprehensive educational resource that consolidates the mechanisms, risks, and trade-offs across various stablecoins. This series aims to fill that gap. Based on issuer documentation, on-chain dashboards, and explanations from project teams, this guide provides investors with a framework for evaluating stablecoins.

The series consists of four parts. The first part introduces stablecoins, covering their design and history. The remaining three will focus on the three dominant categories of stablecoins today:

-

Fiat-backed stablecoins (Part Two)

-

Multi-collateral stablecoins (Part Three)

-

Synthetic dollar models (Part Four)

Each article outlines aspects such as reserve management, opportunities arising from yield and incentive mechanisms, accessibility and native integration of token acquisition, and token resilience based on governance and compliance. Each will also explore external dependencies and pegging mechanisms—factors determining whether a stablecoin can maintain its value during periods of market stress.

Part Two of the series begins by examining fiat-backed stablecoins, the most prevalent and straightforward design today. Parts Three and Four will assess more complex types, including multi-collateralized stablecoins and synthetic dollar models. These deep dives provide investors with a comprehensive framework to understand the underlying assumptions, trade-offs, and risk exposures associated with each type.

Please enjoy Part One of the series.

Stablecoins: The ChatGPT Moment for Crypto

The emergence of stablecoins marks a pivotal turning point in the evolution of the cryptocurrency industry. Today, governments, institutions, and individual users alike recognize the benefits of leveraging blockchain technology to streamline global financial systems. The development of cryptocurrencies has demonstrated that blockchains can serve as a viable alternative to traditional finance, enabling digital-native, global, real-time value transfer—all through a unified ledger.

This recognition, combined with global demand for the U.S. dollar, creates a unique opportunity to accelerate the convergence between crypto and traditional finance. Stablecoins sit precisely at this intersection, relevant to both traditional institutions and governments. Key drivers behind the adoption of stablecoins include:

-

Traditional institutions striving to maintain relevance amid modernization of the global payments landscape.

-

Governments seeking new creditors to finance fiscal deficits.

Despite differing motivations, both governments and incumbent financial institutions understand that they must embrace stablecoins—or risk losing influence as the financial landscape evolves. Recently, Lorenzo Valente, Head of Digital Asset Research at ARK, published a detailed paper on this topic: “Stablecoins Could Become One of the U.S. Government’s Most Resilient Financial Allies.”

Today, stablecoins have moved beyond being niche tools for crypto traders, with retail adoption accelerating rapidly. They have become primary vehicles for cross-border remittances, decentralized finance (DeFi), and access to the U.S. dollar in emerging markets where local fiat currencies lack stability. Despite rising utility and adoption, the complex structures and mechanisms underpinning stablecoins remain opaque to many investors.

Understanding Stablecoins

A stablecoin is a tokenized claim issued on a blockchain, entitling holders to an asset worth one U.S. dollar, which may be traded on or off-chain. Backed by collateralized reserves managed via traditional custodians or automated on-chain mechanisms, stablecoins are stabilized through arbitrage-based pegging mechanisms. Designed to absorb volatility, they aim to maintain parity with a target asset—typically the U.S. dollar or another fiat currency.

The strong bias toward dollar-denominated stablecoins is a natural outcome of their alignment with market demand for synthetic dollar exposure in dollar-scarce economies. By combining the stability of the U.S. dollar with the cost efficiency and 24/7 accessibility of blockchain, stablecoins have become highly attractive mediums of exchange and reliable stores of value. This dynamic is particularly evident in markets long plagued by currency instability and limited access to U.S. bank accounts. In this context, stablecoins effectively serve as digital gateways to dollar exposure, reflected in the fastest-growing regions of on-chain activity in 2025: Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Moreover, stablecoins have revolutionized the development of cryptocurrencies, especially decentralized finance (DeFi), by introducing a liquid, low-volatility unit of account. Without stablecoins, on-chain markets would be forced to transact using volatile assets like Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), or Solana (SOL), exposing users to price risk and diminishing the practical utility of DeFi.

By providing on-chain assets pegged to the dollar, stablecoins enhance price discovery and settlement efficiency within DeFi protocols, thereby improving capital efficiency. This stability and reliability are critical for the core infrastructure upon which these new financial markets depend. Consequently, the specific pegging mechanisms and reserve architectures that uphold these properties are vital to their resilience—especially during times of market stress.

Asset or Debt Instrument? Stablecoin Design Creates Material Differences

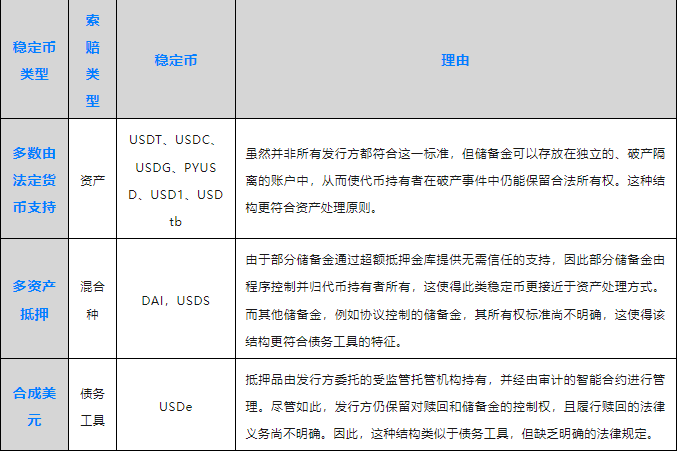

The underlying mechanisms and reserve architectures of stablecoins directly impact their economic and legal behavior. Different designs present trade-offs in regulatory compliance, censorship resistance, degree of crypto-native design, and control versus stability. They also determine how stablecoins operate and what risks, behaviors, and limitations holders face. These nuances raise key questions about how to interpret stablecoins—for instance, whether a particular type should be viewed as an asset or a debt instrument.

In this context, a stablecoin may be considered an "asset" when holders have direct legal ownership of the stablecoin or its supporting reserves, retaining enforceable rights even if the issuer becomes insolvent. Conversely, when the issuer retains legal ownership of the reserves and holders possess only contractual claims—effectively unsecured creditors—the stablecoin functions more like a "debt instrument." This distinction depends on the issuer's legal structure and how reserves are custodied.

The classification of a token largely hinges on who controls the reserves backing it and whether that party bears legal responsibility to fulfill redemption obligations. While most issuers may intend to honor redemptions even under stress, without clear legal obligations or user-controlled reserves, the token operates more like a debt instrument. This distinction determines whether holders retain enforceable claims over the underlying collateral in worst-case scenarios.

The table below outlines differences across stablecoin types in this classification.

Such structures are often carefully designed based on the region, target market, or specific use case the stablecoin addresses. Nevertheless, differences in legal structure can lead to subtle but significant implications for token holders. Notably, this is just one of many interesting cases where intentional or unintentional architectural differences can profoundly impact stablecoins and investors.

Past Stablecoin Failures Are Closely Linked to Design Flaws

Past incidents involving stablecoins decoupling from their designated fiat currencies during crises serve as stark reminders that design differences carry real consequences—particularly under market stress. Indeed, every major type of stablecoin has experienced failure, reflecting inherent architectural flaws and design choices. Below, we discuss some of the most notable failures within each category. This discussion sets the stage for deeper analyses in Parts Two, Three, and Four of this series on "fiat-backed," "multi-collateral," and "synthetic dollar model" stablecoins.

SVB, Silvergate, and Signature Bank Collapses

In March 2023, the collapse of three U.S. banks focused on crypto—Silvergate, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), and Signature Bank—highlighted how fiat-backed stablecoins have long depended on the traditional banking system. Silvergate’s downfall began when it lost access to the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB). Prior to this, rising interest rates at an unprecedented pace by the Federal Reserve had already burdened Silvergate, which held large amounts of long-duration Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. To meet growing withdrawal demands, Silvergate was forced to sell assets at massive losses, accelerating its insolvency and shaking confidence in SVB and Signature, ultimately leading to their collapses.

When Circle disclosed $3.3 billion in exposure to SVB, its stablecoin USDC dropped to $0.89 against the dollar, triggering panic across DeFi and centralized markets until the FDIC stepped in to guarantee all deposits. Within days, USDC recovered its peg. However, the shockwaves affected all stablecoins, including DAI, which temporarily lost its peg due to heavy collateralization in USDC. Later, Circle adjusted its banking partners, but the crisis raised lasting concerns about the fragile link between stablecoins and traditional banks.

Terra/Luna Algorithmic Collapse

In early 2022, Terra was a leading Layer 1 ecosystem centered around the algorithmic stablecoin UST and its native token Luna. Anchor, a lending protocol built on Terra, offered depositors a guaranteed 19.5% yield and served as the primary capital inflow into the TerraLuna ecosystem. UST maintained its peg through an arbitrage mechanism: 1 UST could be exchanged for $1 worth of Luna; minting UST burned Luna, while redeeming it minted new Luna. Although Terra’s leadership later added BTC and other crypto reserves, these never exceeded around 20% of UST’s supply, leaving the system largely undercollateralized. At its peak, TerraLuna attracted billions in capital despite limited real-world use cases, with high yields sustained primarily by subsidies rather than genuine borrowing demand.

When market conditions shifted and Luna’s price fell below the value of circulating UST, the redemption mechanism failed. In May 2022, UST’s decoupling from Bitcoin triggered a massive capital outflow. Terra imposed redemption limits, pushing more trading to secondary markets. When redemptions resumed, Luna underwent extreme inflation to absorb fleeing capital, increasing supply from hundreds of millions to trillions, causing its price to plummet. Bitcoin reserves were insufficient to halt the downward spiral. Within days, the combined market cap of UST and Luna erased over $50 billion.

DAI’s "Black Thursday"

On March 12, 2020, the MakerDAO (now Sky Protocol) community suffered a disaster known as "Black Thursday." A sharp drop in Ethereum’s price and network congestion caused systemic failures in DAI’s liquidation mechanism. Ethereum’s price fell over 40%, pushing collateral ratios of hundreds of vaults below threshold levels. Normally, liquidations occur via on-chain auctions where "keepers" bid DAI for collateral. However, on Black Thursday, high gas fees and oracle update delays caused many bids to fail, allowing speculators to win collateral at near-zero cost. Over 36% of liquidations occurred at 100% discount, resulting in a $5.67 million shortfall and severe losses for vault owners.

Making matters worse, as borrowers rushed to buy DAI to repay debts, DAI itself went into premium, breaking its peg upward. Typically, arbitrageurs would mint new DAI to meet demand, but network congestion, price volatility, and oracle delays prevented this. The combination of liquidations and minimal issuance created a supply shock, while demand surged, driving up the peg. MakerDAO responded with debt auctions and issued Maker (MKR)—its now-deprecated utility token—to recapitalize the protocol. The crisis exposed vulnerabilities in DAI’s liquidation design and the stability of stablecoins under stress, prompting Maker to overhaul its liquidation engine and collateral model.

Stablecoin Design Matters

The collapses of Silvergate, SVB, and Signature Bank; the algorithmic implosion of TerraLuna; and DAI’s "Black Thursday" all underscore the critical importance of stablecoin architecture. These crises highlight how design choices affect system resilience and risk. TerraLuna’s collapse revealed the structural fragility of purely algorithmic stablecoins, demonstrating that systems lacking sufficient collateral or genuine economic utility are inherently unstable and prone to collapse under pressure.

In contrast, the temporary de-pegging of USDC and DAI, while concerning, proved short-lived and prompted meaningful reforms in both ecosystems. After the SVB crisis, Circle increased transparency around its reserves and strengthened banking relationships; MakerDAO (Sky Protocol) not only diversified its collateral basket to include more real-world assets (RWA) but also upgraded its liquidation mechanism to prevent cascading defaults.

What unites these events is their exposure of each stablecoin type’s weaknesses and the specific circumstances most damaging to them. Understanding how these architectures evolved in response to past failures is crucial to assessing today’s design choices and distinctions. Not all stablecoins face identical risks, nor are they optimized for the same goals. Both outcomes stem from their respective underlying architectures. Recognizing this is essential to understanding where stablecoins are vulnerable and how best to use them.

Conclusion

This article introduced stablecoins and argued for the importance of stablecoin design. In Parts Two through Four of this guide, I will examine the three dominant types: fiat-backed, multi-collateral, and synthetic dollar models. Each differs in resilience and trade-offs—differences as significant as their utility or user experience. The unique design, collateral, and governance characteristics of each stablecoin type (and stablecoins themselves) are key determinants of their respective risks and expected holder behaviors.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News