How powerful is the U.S. President's pardon power?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

How powerful is the U.S. President's pardon power?

When granting pardons, the president typically conveys his views on justice, mercy, norms, and social customs.

By Gregory Korte, Bloomberg

Translated by Luffy, Foresight News

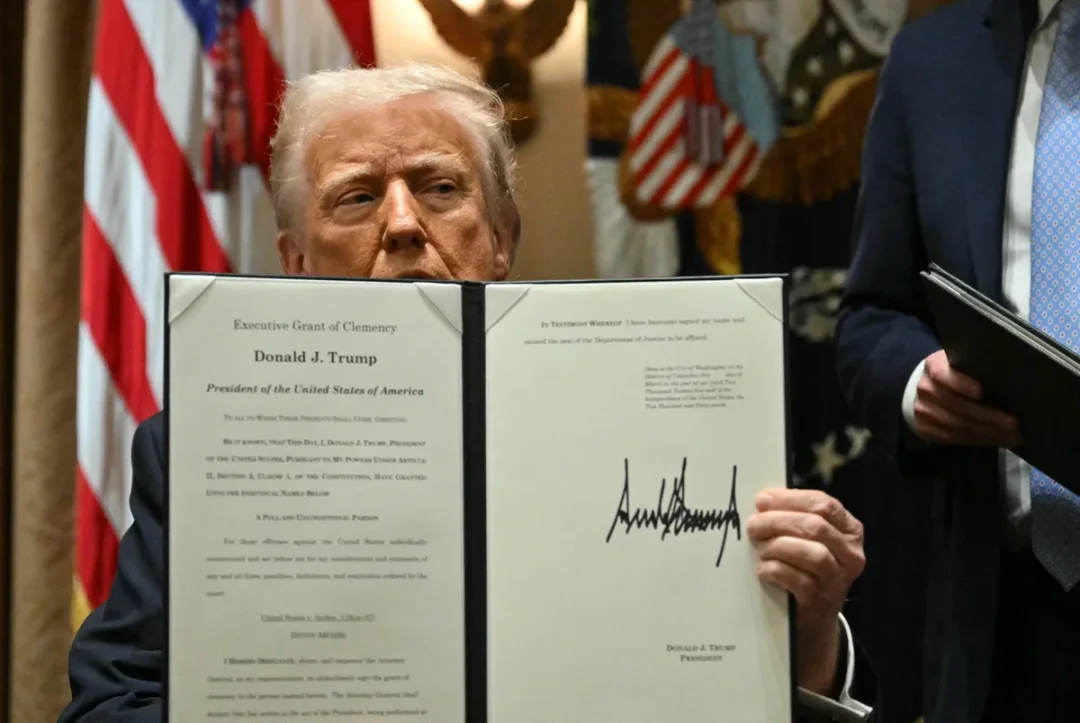

U.S. President Donald Trump signs a series of executive orders, including a pardon, in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington

The U.S. president's pardon power is one of the most absolute and widely misunderstood clauses in the Constitution. As Alexander Hamilton noted, this authority originates from the merciful privileges of 7th-century British monarchs. The American Founding Fathers intended to grant the president strong clemency powers to provide an accessible route for relief to those unjustly convicted within the judicial system.

Today, this power is as controversial as the individuals who wield it. On the first day of his second term, President Donald Trump issued a broad pardon to those convicted in connection with the January 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot.

Trump’s predecessor, Joe Biden, pardoned his son Hunter on tax and gun-related charges in the weeks before leaving office. He also granted so-called "blanket pardons" to five family members, citing concerns they might face unjust prosecutions under a Trump administration. Government officials previously targeted by Trump as political enemies and threatened with punishment were similarly pardoned.

President Donald Trump speaks after signing a pardon at the White House on March 25

What is a pardon?

A pardon is a legal forgiveness of a crime granted by the president, governor, or other executive authority. In some U.S. states, governors must exercise this power jointly with a pardon board, but only the president holds sole authority over federal offenses.

A pardon does not erase a conviction—the record remains—and it does not constitute a declaration of guilt or innocence. Pardons fall under the president’s broader executive clemency powers, which also include these lesser forms:

-

Commutation: reduces the sentence while maintaining all other consequences of the conviction;

-

Reprieve: delays the imposition of punishment;

-

Fine remission: reduces or eliminates monetary fines.

In modern times, reprieves and fine remissions are rarely used.

How often do presidents use the pardon power?

Every U.S. president except William Henry Harrison and James Garfield, both of whom died in office, has exercised the pardon power. Since George Washington first pardoned someone for “using less than 50-gallon casks to smuggle rum from Barbados,” nearly 35,000 individual presidential pardons have been issued.

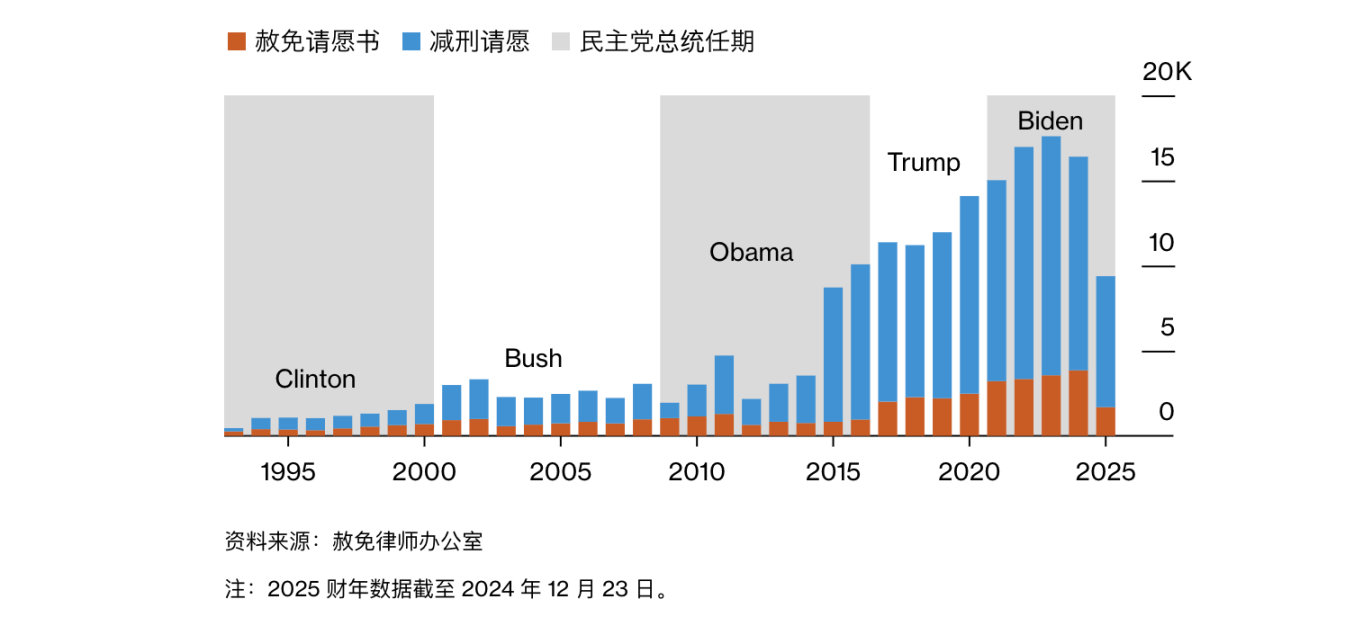

In recent decades, the use of this power has declined, with presidents typically acting around holidays or at the end of their terms.

Biden, however, has been an active user of clemency. Before leaving office, he released 1,499 prisoners under home confinement, including some convicted of public corruption; commuted 37 death sentences; and shortened the sentences of 2,490 drug offenders, whom he said had received disproportionately harsh punishments.

By his final day in office, Biden had issued 79 pardons and 4,168 sentence commutations—making him the most prolific user of executive clemency in U.S. history. The number of pardons he granted in a single term exceeded the combined total of the previous seven presidents.

Why do presidents issue pardons?

When issuing pardons, presidents often express their views on justice, mercy, norms, and social customs.

Pardon lists serve as a mirror of American social history, with each president striving to reconcile past conflicts and help the nation move beyond more punitive eras. Wars, rebellions, Prohibition, and the war on drugs have all been followed years or decades later by waves of leniency.

Leaders of the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers groups involved in the January 6 riot speak at a press conference on Capitol Hill in Washington on February 21

Trump’s pardon of January 6 participants follows clear precedent. In the 1790s, Washington pardoned 10 leaders of the Whiskey Rebellion, who had been convicted of treason; Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson pardoned Confederate soldiers; and Gerald Ford pardoned their general, Robert E. Lee.

Some pardons appear self-serving. Richard Nixon pardoned influential labor leader Jimmy Hoffa, convicted of jury tampering and fraud, who later supported Nixon’s re-election campaign; Bill Clinton pardoned financier Marc Rich, whose wife was a major donor to Clinton’s campaigns, even though Rich faced charges of tax evasion and oil trading with Iran during an embargo; on October 23, Trump pardoned Binance founder Changpeng Zhao, who had served four months in federal prison for failing to establish effective anti-money laundering controls at the cryptocurrency exchange. Prior to the pardon, Zhao and Binance had become key supporters of World Liberty Financial, a cryptocurrency venture backed by the Trump family.

What are the limits on the pardon power?

The Founding Fathers intentionally placed few conditions on the pardon power. Hamilton wrote that it should be free from constraints and obstacles.

The Supreme Court has ruled that since the pardon power is explicitly granted by the Constitution, any limitations (if they exist) must come from the Constitution itself.

In other words, a pardon is valid as long as it doesn’t violate another constitutional provision. Such unconstitutional cases are extremely rare: some commentators argue that accepting a bribe in exchange for a pardon could invalidate it, but this remains legally untested.

The Constitution explicitly sets two limits: first, the president can only pardon federal crimes, not state-level offenses; second, the power does not extend to impeachment cases, meaning the president cannot use pardons to block Congress’s ability to remove themselves or other officials through impeachment.

Can a presidential pardon be revoked?

Neither Congress nor the courts can overturn a presidential pardon. However, the president may revoke a pardon if the official document has not yet been delivered and accepted by the recipient.

In 2008, George W. Bush pardoned real estate developer Isaac Toussie, who had been convicted of mail fraud. But the next day, after learning that Toussie’s father had donated to Republicans, Bush withdrew the decision and ordered that the pardon document not be delivered. Because Toussie never received the paperwork, the pardon did not take effect.

A president may also attempt to revoke an un-delivered pardon issued by a predecessor. In 1869, Andrew Johnson granted pardons to three people convicted of fraud, but days later, upon Ulysses S. Grant’s inauguration, the incoming administration recalled U.S. marshals tasked with delivering the documents, effectively nullifying the pardons.

Can a president pardon himself?

Most legal scholars say no, partly based on the literal wording of the Constitution. It states the president has the power to “grant” pardons—meaning to “give” or “transfer”—which implies the act must be directed toward others. Additionally, in 1974, before Nixon resigned, the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel concluded in a legal memo that, under the fundamental principle that “no one may be a judge in his own case,” a president cannot self-pardon. In any case, Ford later pardoned Nixon for any potential crimes committed during the Watergate scandal.

But this issue has never been tested in court, and even scholars opposed to self-pardons acknowledge it remains unresolved. However, there is a workaround: a president could temporarily transfer power to the vice president, allowing the latter, as acting president, to issue the pardon.

Can someone be pardoned before being charged?

No. A president cannot pardon someone for a crime not yet committed—that would amount to a lifetime immunity pass.

However, a president may pardon someone who has already committed a crime but has not yet been charged. In an 1866 landmark ruling in Ex parte Garland—a case involving a former Confederate soldier—the Supreme Court held that the pardon power applies to all offenses defined by law and can be exercised at any time after the offense, whether before legal proceedings begin, during them, or after conviction and sentencing.

What is a “blanket pardon”?

A president need not specify individual crimes when granting a pardon—this is known as a “blanket pardon.” The most famous example is Ford’s pardon of Nixon, which covered all crimes Nixon may have committed during his presidency.

Biden’s pre-departure pardons of family members and officials targeted by Trump as enemies also fall into this category. Relatives included three siblings and their two spouses; officials included retired General Mark Milley, infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci, and members and staff of the committee that investigated the January 6 attack and recommended prosecuting Trump.

Former U.S. President Joe Biden signs executive orders at the White House

Committee members included former Republican Representative Liz Cheney of Wyoming, who helped lead the investigation, and current California Democratic Senator Adam Schiff, who led Trump’s first impeachment trial. Biden also pardoned Capitol Police and Metropolitan Police officers from Washington, D.C., who testified before the committee.

Biden’s pardon of his son Hunter covers not only his already-convicted gun and tax offenses but also any other potential crimes committed during the prior 11 years.

During his first term, Trump also pardoned several allies, including former political adviser Steve Bannon and Albert Pirro Jr., former husband of Fox News host Jeanine Pirro.

Does accepting a pardon mean admitting guilt?

No. Presidents often pardon individuals they believe are innocent or victims of injustice. For example, Trump posthumously pardoned boxer Jack Johnson, convicted in 1913 of transporting a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes”—a charge frequently used as a racially motivated prosecution; Biden pardoned service members convicted under the now-repealed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy; and among his final acts, he pardoned Marcus Garvey, a Black nationalist leader convicted in 1923 of mail fraud—a prosecution long viewed by civil rights activists as racially driven.

The common belief that “a pardon implies guilt” stems from the 1915 Supreme Court ruling in Burdick v. United States, which stated that accepting a pardon carries an implicit admission of guilt. Ford carried a copy of this ruling in his wallet as justification for pardoning Nixon.

However, later courts have not treated this implication as central to the Burdick decision. The core holding was that recipients of pardons have the right to refuse them.

Must a pardon be in writing?

In February 2024, a federal appeals court ruled: “The answer is clearly no. The plain text of the Constitution imposes no such requirement.”

But from practical and historical standpoints, having a written record is safer. In the 2024 ruling, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals determined that Trump’s verbal assurances to former Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown—statements like “I’ll take care of it” and “I want this done”—were insufficient to release a man serving life sentences for drug trafficking and murder.

Must the president name the person being pardoned?

No. There is precedent for categorical pardons—broad forgiveness for all those convicted of a specific crime. For instance, Jimmy Carter granted amnesty to Vietnam War draft evaders; Biden implemented categorical pardons for marijuana-related offenses. In such cases, individuals convicted under specific laws may apply to the Office of the Pardon Attorney at the Department of Justice for a certificate confirming their eligibility.

Number of pending presidential pardon applications at the Office of the Pardon Attorney by fiscal year

How does one obtain a pardon?

There are two procedural paths to a pardon:

The first follows the process used by Barack Obama. Applicants submit requests to the Office of the Pardon Attorney. The office typically requires applicants to wait five years before applying and does not accept posthumous or misdemeanor-only petitions. After thorough review—including an FBI background check—applications go to the Attorney General, then to the White House Counsel’s Office, and ultimately to the president for approval or denial.

The second path, favored by Trump, is far looser. During his first term, he frequently bypassed waiting periods and background checks, relying instead on recommendations from celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Sylvester Stallone, and announcing pardons during high-profile ceremonies.

Most presidents use a mix of both approaches, while controversial pardons are often processed through direct presidential channels.

One reason for bypassing bureaucracy: under Biden, the backlog of pardon applications reached record highs, only returning to pre-Trump levels after he cleared a large batch of applications just before leaving office.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News