Former PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan: Examining Stablecoins from Multiple Dimensions

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Former PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan: Examining Stablecoins from Multiple Dimensions

A comprehensive analysis from central bank regulation to market manipulation.

Author: Zhou Xiaochuan, former PBOC Governor

Source: China Finance 40 Forum

Note: This article is compiled from part of the speech delivered by Zhou Xiaochuan, former Governor of the People's Bank of China, at CF40’s biweekly closed-door seminar on "Opportunities and Prospects for RMB Internationalization" on July 13, 2025. Its main content originates from a speech given on June 5, 2025, at the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) Frankfurt Annual Conference, with minor adjustments.

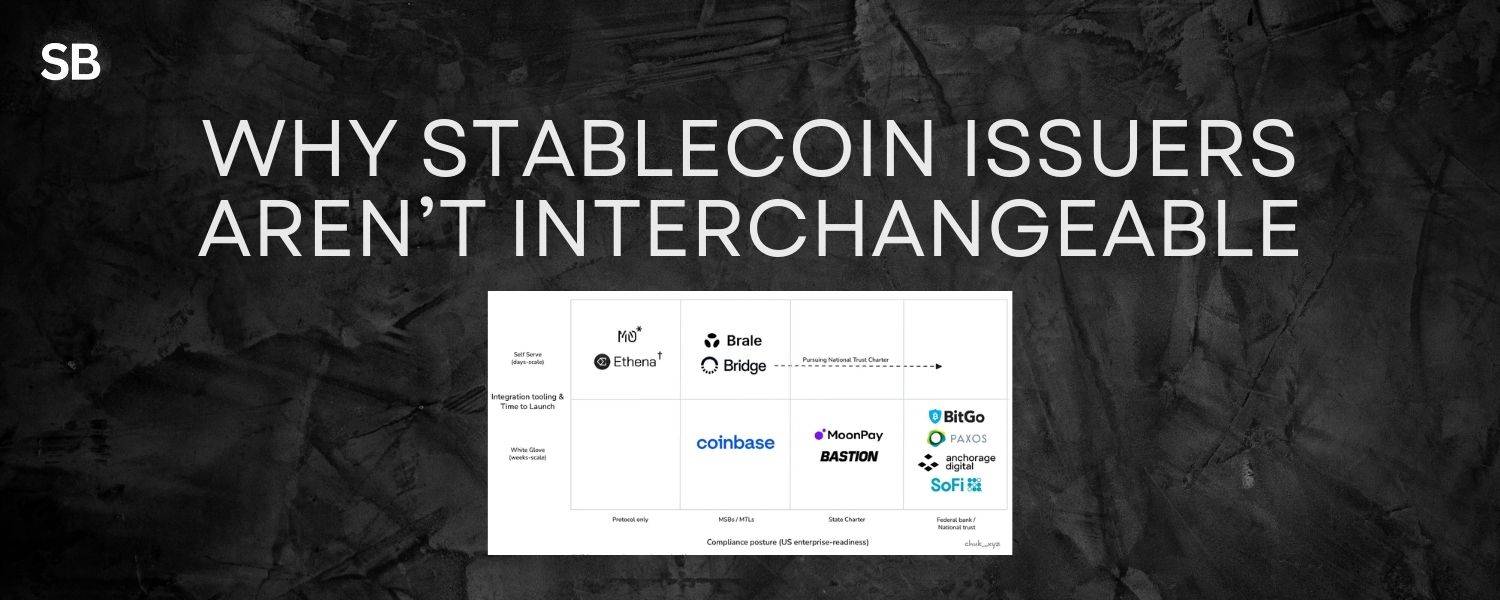

Current discussions on stablecoins often stem from a single perspective. To properly assess the operation and future prospects of stablecoins, multidimensional and multifaceted scrutiny is required. If we aim to advance the development of digital payment systems in a healthy manner, we must also pay attention to performance and balance across multiple dimensions.

1. Central Bank Perspective: Preventing Excessive Money Issuance and High Leverage Amplification

Stablecoin issuers may seek to minimize their own costs while maximizing issuance scale and application. They might wonder: if central banks can print money, why can't they? Today, through stablecoins, they effectively gain money-printing capabilities—but due to insufficient understanding and sense of responsibility regarding monetary policy, macroeconomic regulation, and public infrastructure functions, they may lack adequate self-discipline, potentially leading to uncontrolled issuance, high leverage, and instability. Whether a stablecoin is truly stable cannot be self-declared; it requires an objective verification mechanism.

Central banks currently have at least two concerns. First is "excessive money issuance," where issuers release stablecoins without holding full 100% reserves—i.e., over-issuance. Second is high leverage amplification, whereby the circulation of issued stablecoins generates a multiplier effect in money creation. The U.S. GENIUS Act and Hong Kong’s Stablecoin Ordinance have both addressed these issues, but enforcement remains clearly inadequate.

First, it must be clarified who holds custody of the reserve assets. In practice, custodians have often failed to fulfill their duties, as evidenced by numerous past cases. In 2019, Facebook initially planned to self-custody Libra’s reserve assets, retaining strong autonomy and earning income from those assets. However, reserve custody must be reliable—conducted either by central banks or institutions recognized and regulated by them; otherwise, reliability cannot be ensured.

Second, how should the amplification effects during stablecoin circulation be measured and managed? Even with 100% reserve backing, stablecoins may still generate multiplier effects during subsequent operations such as lending, collateralization, trading, and revaluation. The potential redemption volume under stress could be several times greater than the initial reserve. While regulations may appear to restrict amplification, a deeper analysis of currency issuance and circulation mechanisms reveals that existing rules are far from sufficient to address derived expansion.

The example of three commercial banks issuing Hong Kong dollar banknotes offers insight: each time these banks issue HKD 7.8, they must deposit USD 1 with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) and receive a Certificate of Indebtedness. Based on this M0 cash supply, the financial system generates M1 and M2 through money multiplication. During a run, demand may target not only M0 but also M1 or M2. Even with full reserve backing for base money M0, the reserve cannot withstand a broader run and maintain currency stability.

There are three well-known channels through which stablecoin amplification occurs: first, deposit-lending channels; second, collateral financing channels; third, asset market transactions (including additional purchases or revaluations of reserve assets). Therefore, regulators must track and measure the actual circulating volume of issued stablecoins; otherwise, the scale of potential redemption risks cannot be accurately assessed. The multiplier effect of stablecoins also creates opportunities for fraud and market manipulation.

2. Financial Service Model Perspective: Real Demand for Decentralization and Tokenization

If the future ecosystem involves large-scale decentralization of financial activities and widespread tokenization of assets and transaction tools, stablecoins would play a significant role. First, stablecoins are compatible with the development of decentralized finance (DeFi); second, tokenization is a necessary foundation for DeFi operations. The key question is: why, and to what extent, will we move toward decentralization and tokenization?

From the supply side, blockchain and distributed ledger technology (DLT) do offer distinctive features enabling decentralized operations. But from the demand side, how strong is the actual need for decentralization as a new operating system? Will most financial services migrate into this new framework?

A sober assessment suggests that few financial services are genuinely suited for decentralization, and even fewer achieve substantial efficiency gains through decentralized methods. The real demand for tokenization as a technological foundation also requires careful estimation.

Looking at expectations for upgrading payment systems—especially cross-border payments—China and several Asian countries have made successful progress developing mobile-based retail payment systems using QR codes and near-field communication (NFC) at merchant endpoints. These remain account-based systems. Currently, China's developed digital currency is also account-based, representing an extension and iterative update of the existing financial system. Additionally, some Asian countries’ fast payment systems use direct cross-border interconnections without adopting decentralized or tokenized models.

To date, centrally managed account systems continue to demonstrate strong applicability. The rationale for replacing account-based payment systems entirely with fully tokenized alternatives remains insufficient.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has proposed a centralized ledger architecture—the Unified Ledger—that enables tokenization of bank deposits and many other financial services within a centralized framework, allowing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) to play a major role—thus combining centralization with tokenization. It must be questioned, however, whether all types of financial assets are suitable for tokenization, or whether every stage of financial service delivery is fit for decentralization. Each case requires individual analysis and comparison.

3. Payment System Perspective: Technological Pathways and Compliance Challenges

Two major concerns drive payment system evolution: payment efficiency and compliance.

Improved payment efficiency is considered one of the potential advantages of stablecoins. In the ongoing digitization of payment systems, there are roughly two pathways to enhance efficiency. The first is continuous optimization and innovation based on traditional account systems, leveraging IT and internet technologies. The second is building entirely new payment architectures based on blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies.

Based on developments in China and Southeast Asia so far, major advances have been achieved primarily through internet and IT technologies—including the growth of third-party payment platforms, progress in central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), NFC-enabled hard wallets, and interconnected fast payment systems. These improvements have significantly enhanced payment efficiency and convenience.

Technology alone is not the sole criterion. Comparisons of payment performance must also place high importance on security and compliance, including Know Your Customer (KYC), identity verification, account opening management, anti-money laundering (AML), counter-terrorism financing (CFT), anti-gambling, and anti-drug trafficking requirements. Some argue that since stablecoins are blockchain-based, account opening is unnecessary. This is inaccurate. Even when using "soft wallets," user identity verification and account opening procedures are still required to meet compliance standards. Currently, stablecoin payment services exhibit clear deficiencies in KYC and overall compliance.

4. Market Trading Perspective: Market Manipulation and Investor Protection

From the standpoint of financial and asset markets, the greatest concern is market manipulation, particularly price manipulation, which necessitates robust transparency and effective regulation. Indeed, such manipulative behaviors already exist and several related cases have occurred, some involving clear elements of fraud. Yet, under current regulatory frameworks—including the U.S. GENIUS Act, Hong Kong’s relevant ordinances, and Singapore’s regulations—these problems remain inadequately addressed.

A new phenomenon is the mixed use of multiple coins, where various currencies are used together in a single system for transactions or payments. Not all components are genuine stablecoins, nor is there a consistent, widely accepted standard for what constitutes a stablecoin. In today’s asset markets, especially on virtual asset exchanges, settlement currencies for trades may include stablecoins, non-stable cryptocurrencies, or even highly volatile tokens. Such arrangements create openings for market manipulation, making this a key focus area for regulators.

Notably, some market promoters claim that using stablecoins and RWA-related technologies allows asset ownership shares to be divided extremely finely, enabling broader investor participation—and assert that this model has already attracted significant numbers of students under age 18.

While some believe this fosters youth engagement in capital markets and supports future market vitality, from an investor protection standpoint, the actual benefits remain uncertain. Historically, emphasis has been placed on investor suitability and qualifications. Whether minors are appropriate participants in asset market trading lacks sufficient justification. If market manipulation cannot be effectively prevented, attracting unqualified investors significantly increases risk exposure.

5. Micro-Behavior Perspective: Motivations of Participants

Stablecoin issuers are typically profit-driven commercial entities. Similarly, most actors involved in stablecoin-related payment and asset trading businesses are commercial institutions, each driven by business incentives. However, stablecoins and payment systems contain elements with infrastructure and inclusive finance characteristics, which cannot be governed solely by corporate profit-maximization logic. Instead, a public service ethos is needed. Clear distinctions must be drawn between areas suitable for market players and those possessing infrastructure-like qualities.

A micro-level analysis of participant motivations and behavior patterns is essential. Why do individuals choose to pay with stablecoins? Why are recipients willing to accept them? What motivates stablecoin issuers? What outcomes do private exchanges seek? Currently, Hong Kong has issued 11 licenses for virtual asset trading platforms—what are these licensed institutions focusing on in terms of trading parties and instruments? How do they generate revenue?

Although many believe stablecoins will reshape the payment landscape, objectively speaking, the current payment system—particularly in retail payments—has little room left for cost reduction. In China, the existing retail payment ecosystem—including third-party platforms, CBDCs, soft and hard wallets, and clearing infrastructure—has evolved over years without adopting decentralization or tokenization, achieving high efficiency and low costs. As a result, new entrants face minimal opportunity to reduce costs and earn profits in this space.

In contrast, the U.S. retail payment system may still offer some cost-saving potential, largely because it relies heavily on credit cards, with merchants typically bearing a 2% discount fee. This creates incentives to explore lower-cost alternatives. This highlights differing dynamics between payer and payee perspectives across countries and regions.

Cross-border payments and remittances are frequently cited as key application areas for stablecoins. To examine this thoroughly, it is essential to break down the reasons behind the high costs of current cross-border payments and identify which specific stages contribute to these expenses.

It should be noted that claims about traditional cross-border payment systems being "extremely expensive" due to technology may be exaggerated. In reality, much of the cost is non-technical, stemming from foreign exchange controls linked to broader systemic issues such as balance of payments, exchange rates, and monetary sovereignty. Another portion comes from KYC and AML compliance costs, which would persist even with stablecoins. Additionally, some costs arise from the "rent" associated with cross-border foreign exchange operations as a licensed business. Overall, the appeal of stablecoins in cross-border payments is not as strong as imagined. Of course, exceptions exist in contexts where domestic currencies have collapsed and dollarization becomes necessary.

From the stablecoin issuer’s perspective, if domestic and cross-border payments offer limited attractiveness, the most likely focus shifts to asset market trading—particularly virtual asset trading. Certain assets in these markets are highly speculative and prone to artificial price inflation, enhancing the appeal of stablecoin issuance. Moreover, some virtual assets can themselves serve as qualified or semi-qualified reserves for stablecoin issuance.

Based on current micro-behaviors, caution is warranted against excessive use of stablecoins for asset speculation. Deviations in direction could lead to fraud and financial instability.

Additionally, industry players may exploit the popularity of stablecoins to inflate their company valuations—a behavior worth monitoring. Some firms may use this momentum to raise funds through capital markets or realize capital gains before exiting, with little regard for the profitability or long-term sustainability of the stablecoin business itself. This trend undermines the healthy development of the financial system and may accumulate systemic risks.

6. Circulation Path Perspective: The Lifecycle from Issuance to Redemption

The circulation path of stablecoins encompasses the entire cycle—from issuance, through market circulation in specific scenarios, to eventual redemption and withdrawal.

Taking the issuance of paper currency by the People's Bank of China (PBOC) as an example, printed notes are first stored in designated issuance vaults. Whether and when these notes enter circulation depends on commercial banks' demand for physical cash. Commercial banks withdraw cash from PBOC vaults only when their customers have net demand or show a lending surplus. Once withdrawn, holding cash incurs occupancy costs for banks, so excess inventory is returned to the vault. This shows that money does not automatically enter circulation.

Likewise, obtaining a license and depositing reserves does not equate to actual stablecoin issuance. Without sufficient demand scenarios, stablecoins may fail to enter effective circulation—meaning issuers might hold licenses but be unable to issue coins. In theory, the circulation path should resemble a network, typically featuring several high-volume main routes. If the primary route via payments is blocked, stablecoins may overly rely on virtual asset speculation to enter circulation, raising serious concerns about systemic health.

Furthermore, whether stablecoins are used merely as temporary transaction media or held as value storage tools over time affects their post-issuance market presence. If users hold minimal balances and use them strictly for transactions, the role of stablecoins weakens, resulting in lower issuance volumes. This involves circulation pathways, holding motives, behavioral patterns, and supporting systems—none of which are automatically granted by simply issuing a license.

In summary, facing this new phenomenon of stablecoins, scholars, researchers, and practitioners must analyze their functions and implementation paths from multiple dimensions, avoiding imprecise concepts, data, and one-dimensional thinking. Only through comprehensive evaluation across critical dimensions can we better steer market development. TechFlow

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News