Culture, Capital, and Cryptocurrency

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Culture, Capital, and Cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrency is a culture and also a medium of expression.

By: Joel John

Translation: Chopper, Foresight News

I often wonder what Michelangelo was thinking when he painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. This work is considered one of humanity’s greatest artistic masterpieces. Yet initially, he didn’t want the job at all. Michelangelo's true domain was marble sculpture—hammers, stone, and the human form were where his genius truly flourished.

At the time he received the commission, he was already burdened with debt for failing to deliver sculptures for a deceased pope’s tomb. Pope Julius II then ordered him to paint frescoes in the chapel. Michelangelo suspected it was a plot by rivals to embarrass him, given the immense difficulty of the task. He found himself trapped between two obligations: an unfinished commission from a dead pope, and a new demand from the current one.

I imagine that in those days, no one dared say “no” to the leader of the Catholic Church. So he accepted the commission and spent four years, from 1508 to 1512, painting the ceiling. He loathed the work intensely and even wrote a poem comparing himself to a crouching cat. A few lines always stand out to me:

My painting has become lifeless. Giovanni, help me protect it, preserve my dignity. I don't belong here — I was never meant to be a painter.

Notice the mention of "Giovanni"? He refers to Giovanni di Pistoia. But there’s another Giovanni relevant to us: Giovanni de' Medici. He was Michelangelo’s childhood friend. As boys, under the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici, Michelangelo was brought into the Palazzo Medici Riccardi.

The Medici family was Europe’s most powerful banking dynasty during the Middle Ages. In modern terms, they’d be like JPMorgan Chase or SoftBank. But more importantly, they were the financial architects—the godfathers—of the Renaissance.

It’s been 520 years since Michelangelo finished the ceiling, and I’m still writing about him partly because some of history’s most prominent bankers backed him. Throughout time, capital and art have intertwined to create what we call “culture.” Most celebrated artworks in society are backed by massive infusions of capital. Michelangelo may not have been the most talented artist of his era.

Now consider how modern media works—it becomes even more interesting. Today’s “Sistine Chapel” isn’t in Europe; it’s on the internet. When you log into X, Instagram, or Substack every day, you’re walking into these digital chapels. Today’s “Michelangelos” don’t wait for Medici patronage—they hope algorithms favor them. The new “Medicis” buy their own “chapels” and imprint their identity upon them. After Elon Musk acquired X, his own posts saw a dramatic increase in views within months. New “gods” are building their own “churches.”

Technology accelerates cultural change. In this age of 9-second videos, memes are the LEGO blocks of culture—but they still need capital to scale. Without tens of billions in funding and legal protections shielding founders from prosecution over platform content, platforms like Facebook might never have existed.

Today, technology acts as a lever to transform culture by expanding the scope of human expression. All technologies leave cultural imprints because they alter the medium through which people express themselves.

I’ve been reflecting on how technology, culture, and capital converge over time. Once a technology scales, it attracts capital. In this process, the technology often constrains its own expressive potential. For example, in crypto, we no longer preach radical decentralization but talk about better unit economics; we no longer call banks “evil,” but praise how they distribute digital assets. This shift fascinates me—it affects everything from founders’ fundraising pitches to CMOs defining brand narratives.

But before diving deeper, let’s quickly review the evolution of media itself.

Evolution

Humans are expressive machines. From using plant juice to draw on cave walls, we've constantly left traces of our thoughts—about animals, gods, lovers, desire, and despair. When expressive mediums form networks, our expressions grow richer.

You may not have noticed, but our logo is a manual printing press—a tribute to Gutenberg and a nod to the irony of information dissemination. In the late 15th century, when Gutenberg printed the Bible, he likely had no idea how profoundly his invention would spread information.

By the 17th century, almanacs (or dense scientific texts) became the primary reading materials across Europe. The ability to print and circulate ideas helped drive the Scientific Revolution. You could now say “Earth isn’t the center of the universe” without being executed.

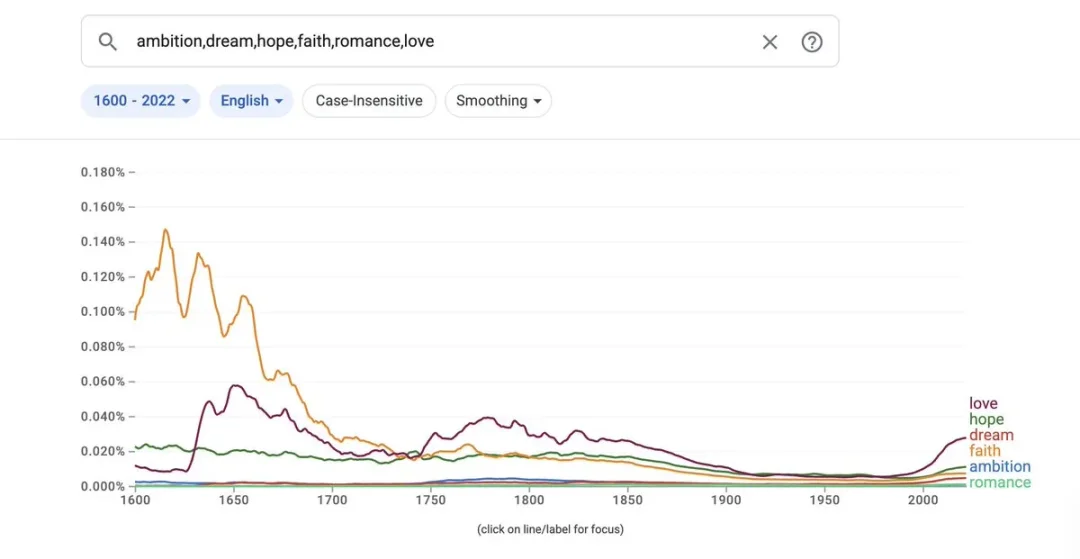

The word frequency chart above shows a decline in references to “faith” in literature, replaced by “love.” Of course, I’m not suggesting all of Europe abandoned religion to find better partners—rather, the nature of the medium changed. Tools originally used to spread faith (like the printing press) may have ironically contributed to its decline.

The printing press illustrates how once an information tool or technology is released, its uses become unpredictable.

It transformed written language from a “public good” into a “private good.” Around the 18th century, silent private reading in bedrooms became increasingly common. This makes sense—before mass printing, books and literacy were rare.

Back then, reading was social: groups gathered while one person read aloud. As book prices dropped and elites gained leisure time, silent reading spread. At the time, fears arose about losing control over disseminated ideas—moral panics erupted.

Families worried youth would spend free time reading love stories instead of contributing to the Industrial Revolution. Clearly, the medium shifted from public to private—from temple sculptures and monasteries to privately held printed pamphlets. This changed the nature of shared ideas: from highly religious to scientific, romantic, and political. Before print, such private circulation simply didn’t exist.

Churches, kings, and nobles had no incentive to publish essays on power structures.

This may have fueled political upheavals at the end of the 18th century, when both France and America decided it was time to change governance. Let’s not get bogged down—we still have a century of media evolution to cover: radio, television, and the magnificent internet!

In the coming century, revenue models will reshape media. Broadcast media like radio and TV rely on reaching as many people as possible simultaneously. This means avoiding niche topics. Prime-time TV rarely features steamy romance dramas—it’s designed for the whole family to watch together.

Broadcast viewpoints almost always align with prevailing social norms.

From Ben Thompson’s article

Ben Thompson brilliantly captured this shift in his piece “Never-Ending Niches.” In the 1960s, I’d have had no outlet to write about emerging tech or find enough online readers. As a creator, I’d be limited to local audiences. The internet changed that—I can now reach anyone globally interested in the digital economy. Our readers come from 162 countries.

All thanks to the power of networks. This scale also transforms how culture spreads.

J.K. Rowling’s *Harry Potter*, Jay-Z’s album *The Blueprint*, and Dr. Dre’s headphones share something: they’re exceptional creative works that became centers of capital. They created a flywheel—money amplifies art, and art increases money’s value.

Yet a common thread behind these shifts is technology.

Platforms like YouTube, Kindle, and Apple Music brought their work to global audiences. Culture is no longer centered on their hometowns but consumed and embraced internationally. This vastly expanded their audience, improving unit economics. In turn, platforms benefit from users engaging with these products.

When trying to attract mass users to a product, shared culture is the easiest entry point. I previously wrote about how SuperGaming used well-known IPs to promote games—downloads now exceed 200 million.

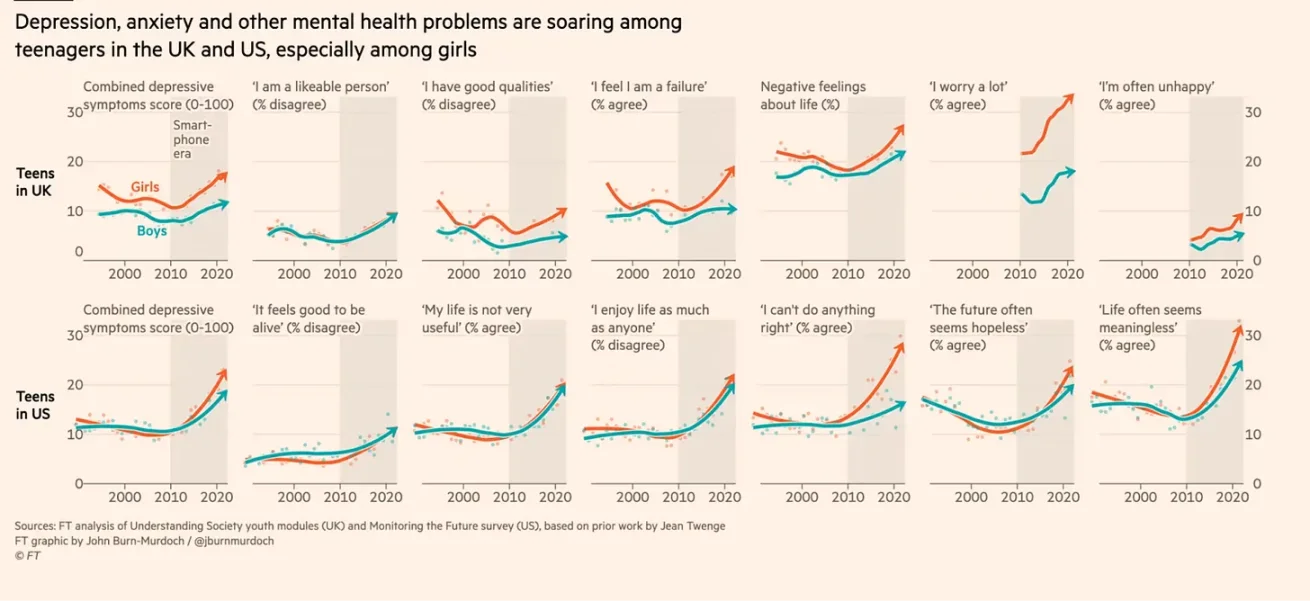

From Financial Times

In the age of AI and algorithmic feeds, culture tends toward centralization. Today’s teens don’t need to search hard for new media—they fall into content loops reinforcing their worldview. Large language models (LLMs) intensify this risk: instead of seeing human-created content, people converse with chatbots that reinforce existing beliefs. This can have deadly consequences, including suicide. On the other hand, the same tools are increasingly used in mental health therapy.

This duality defines internet technologies: on one hand, it’s the best place for a boy in rural India to discover top artists and dream of becoming one; on the other, it’s the best place to find harmful ideas and spiral into self-reinforcing content loops. This explains why society feels increasingly divided: we don’t converse—we get reinforced by algorithms.

We no longer have legends—only content; depth sacrificed for virality in niche circles. If it drives clicks, why care about truth?

When everyone gets only 15 seconds of fame, we sacrifice narrative subtlety for catchy hooks and flashy moments. Timeless stories, emotions, and virtues are compressed into dopamine hits between meetings. Human experience becomes endless swiping—like pulling slot machine levers in a modern casino, chasing resonant content.

What does this have to do with cryptocurrency? To understand, we must examine how the industry evolved.

Shift

From Michelangelo to Jay-Z, from the Medicis to SoftBank, one thing is clear: capital enables cultural scaling. When culture ties to monetary stability, more people adopt it. Technologies like the printing press, radio, and the web enable cultural dissemination. Creating art requires capital; so does distributing it.

But what happens when the medium of expression itself becomes money? That’s the trillion-dollar question the crypto industry is trying to answer.

Crypto began with the intent to replace banks using cypherpunk values. It makes sense—many on Satoshi Nakamoto’s Bitcoin whitepaper mailing list had faced trouble for encryption work. In the early 1990s, exporting encryption software was treated like exporting nuclear weapons. So early distrust of governments was deeply rooted.

Bitcoin’s early adopters weren’t fintech enthusiasts but drug markets like Silk Road and organizations like WikiLeaks, cut off from banking. In 2011, when WikiLeaks adopted Bitcoin after PayPal suspended its services, Satoshi said they’d “poked the hornet’s nest.” Bitcoin was still fringe. Ethereum’s 2014 ICO brought broader attention.

Uber? Put it on-chain. Tinder? On-chain too. Your local government? On-chain! We’ll put everything on-chain, tokenize it all—because the world needs more decentralization. Just kidding.

Two factors drove this:

-

Ethereum’s smart contracts made issuing, transferring, and trading assets easy;

-

On-chain fundraising was novel—founders could bypass “evil” VCs and raise funds directly from communities.

ICOs gave liquidity to venture investments and allowed retail participation. The optimistic vision was that VC’s business model would be disrupted. The culture then revolved around shared ownership and distributed governance delivering better outcomes.

Like many chapters in financial history, this period brimmed with vibrant optimism—until asset prices fell.

As the market evolved, crypto split into two user types: quant traders and “farmers.”

-

Quant traders are typically sophisticated operators who use capital pools, information channels, and deep financial understanding to accumulate wealth.

-

“Farmers” are regular crypto users who perform raw labor for protocols. I count myself among them—most of my crypto comes from working for protocols. The long tail includes users willing to go the extra mile for airdrops.

You don’t even need to issue a token—just call it “points” and paint a vision.

With the harsh reality of bear markets, we shifted from “wanting to overthrow governments” to “hoping for airdrop subsidies.”

Suddenly, decentralization wasn’t the focus—instead, it was which token might be deemed most valuable. This mirrored media evolution, shifting from private consumption to social reputation. By 2019, the ICO craze faded—no one could raise funds just by launching a token.

But pricing signals changed. Markets began valuing tokens based on “which VCs invested” or “which exchange it might list on.”

Like any nascent industry, we fumbled to find our voice. Should I call everyone “sir”? Do I really need to attend DAO meetings? Who cares.

We mistook large Discord chat groups for “communities,” assumed tokens were products, and treated token price as proof of product-market fit. We ignored that billion-dollar protocols often earned less than $100 daily. We confused founders’ ability to talk about problems with actual execution. Above all, we mistook jargon for innovation and competence.

Only when Bitcoin surged during the ETF boom while most altcoins lagged did we realize “the emperor has no clothes.”

The 2024 meme coin revival signaled the market recognized “volatility itself is the product.” As long as prices rise and token distribution appears fair, people will trade. From WIF and Fartcoin to countless meaningless assets, we realized speculative assets can also be expressive mediums. The shared emotion across all these assets? A hunger for profit.

Crypto culture shifted from ideology or technology to behavior enabled by the ecosystem—trading became central. It makes sense: if blockchains are financial rails, their core use should be fast, efficient value transfer. Yet within this, different choices emerged, revealing a parallel culture forming in crypto.

Most scalable products touch behaviors that seem odd to outsiders. Layer3 is easily mistaken for an airdrop “farmer” tool, but closer inspection reveals a full-stack solution bringing millions into Web3. They offer on-chain reputation tools, wallets, swaps, and support more chains than anyone. What might be seen as a “task platform” is now essential for early product growth.

Who could have predicted this back in 2021?

Likewise, NFTs were dismissed as outdated tech, yet Pudgy Penguins proved otherwise. They partnered with Walmart, generating over $10 million in revenue. Their brand assets have been viewed nearly 120 billion times, averaging 300 million views daily. Pudgy used crypto-native tech but made it meaningful in a completely different way—partnering with retailers and leveraging Web2 social networks for visibility.

Both products raise a question: what is crypto culture? Blind speculation on meme coins? Getting liquidated daily on perpetual exchanges? Betting your entire net worth on a token launched last night because AI will disrupt jobs and you’ve got less than two years to escape the “perma-middle class”?

The market has answered: crypto is both a medium of expression and a trading culture. Consumers accept its ability to reliably transfer value—that’s why stablecoins dominate global remittances. But they’ve rejected other ideas—“play-to-earn” failed miserably. Despite my hopes, content tokens haven’t taken off either.

It’s sad—I see friends sharing content on Instagram daily, yet I have no idea how much my content on Zora is worth.

Just as free speech means nothing without offensive speech, global resource coordination is hard without bad actors exploiting markets. In both cases, actions have consequences. Perform poorly long-term, and no one listens or buys your assets. Ironically, Crypto Twitter may be facing both outcomes simultaneously.

We must admit crypto’s evolution mirrors that of most media. We don’t notice thousands of books fading into irrelevance, or millions of blogs nobody reads. Social media works because content expires within a day. Crypto assets will be similar—over 40 million tokens exist, many destined to hit zero. One day, people might nostalgically recall content tokens like 2021 NFTs or 2017 ICO tokens.

Irrelevance is the default for most things—unless culture intervenes.

Culture is often defined by how it communicates. Language shapes how we perceive and understand the world. Before 2021, speaking in jargon was fine, but to break beyond our niche, we must speak in ways others understand.

For instance, your dating app shouldn’t just boast zero-knowledge proofs—people want dates. Stablecoin competition isn’t about network count—people pick the cheapest, fastest global transfer method. Consumers care about immediate utility, not future “layered visions.”

The closer our industry gets to consumer products, the more we need to speak in language ordinary internet users understand. Since language is shaped by environment and interaction frequency, we must rethink how we onboard and retain users.

The new “Medicis” will be those who command attention. Ironically, the new “Michelangelos” will be artists who define capital flows.

Reprieve

One way to think about crypto is through casinos and your local coffee shop. Money moves fast in casinos—people frequently shift funds across products, but the house usually wins. You won’t see people permanently “settling in” at casinos—at least, most won’t. In contrast, community cafes attract repeat visitors daily.

Often the same group gathers, using coffee as an excuse to share stories and vent. It’s the calm and comfort of the space that keeps them coming back. In more religious societies, temples or churches serve similar roles. Coffee or faith becomes the base layer, but people stay for reasons far beyond the product itself.

Culture is the collection of stories people share with each other. Today, our shared stories are often price charts—and when the chart turns green, people have little reason to return. How do we sustain engagement? How can this technology cross the chasm?

To understand, perhaps look at the internet itself. Two forces shape networks:

-

In the age of AI and LLMs, vast amounts of content are generated. When everyone is a creator, no one truly is. People need mechanisms to own, monetize, and distribute their content.

-

Verifiability. In attention economies like X or Instagram, oceans of AI-generated “garbage” keep users engaged—more eyeballs mean more clicks, more money.

Everything crypto offers the internet ultimately ties to verifiability and ownership. These ideas aren’t new—we’ve discussed them in this publication since 2023. But regulatory shifts and changing attitudes among capital allocators make now the right time to seize these opportunities.

The internet has always been a tool for free expression. Crypto lets people own the channels and networks through which they express themselves, and freely issue, trade, and hold assets. When everyone can express themselves monetarily, meme coin mania follows.

When the internet emerged, most marveled at how it would change work, but ordinary users weren’t drawn by job prospects—they came for entertainment and connection. Meme assets are like entertainment in the crypto era, but due to associated losses, they lack “Lindy effect.” Perhaps not everything should be tradable.

Only about 1% of internet users create content. By analogy, in crypto, perhaps a world exists where users spend 99% of their time in apps without trading. The magic of next-gen consumer apps lies in finding ways to engage users without making “trading” the core value proposition.

I know this sounds ironic. On one hand, we say blockchain is financial rails and everything is a market; on the other, we admit constant trading leads to churn. As they say, attention is what you really need.

So what now?

Early signs emerge from social networks and entertainment:

Social Networks Built Around Prediction Markets

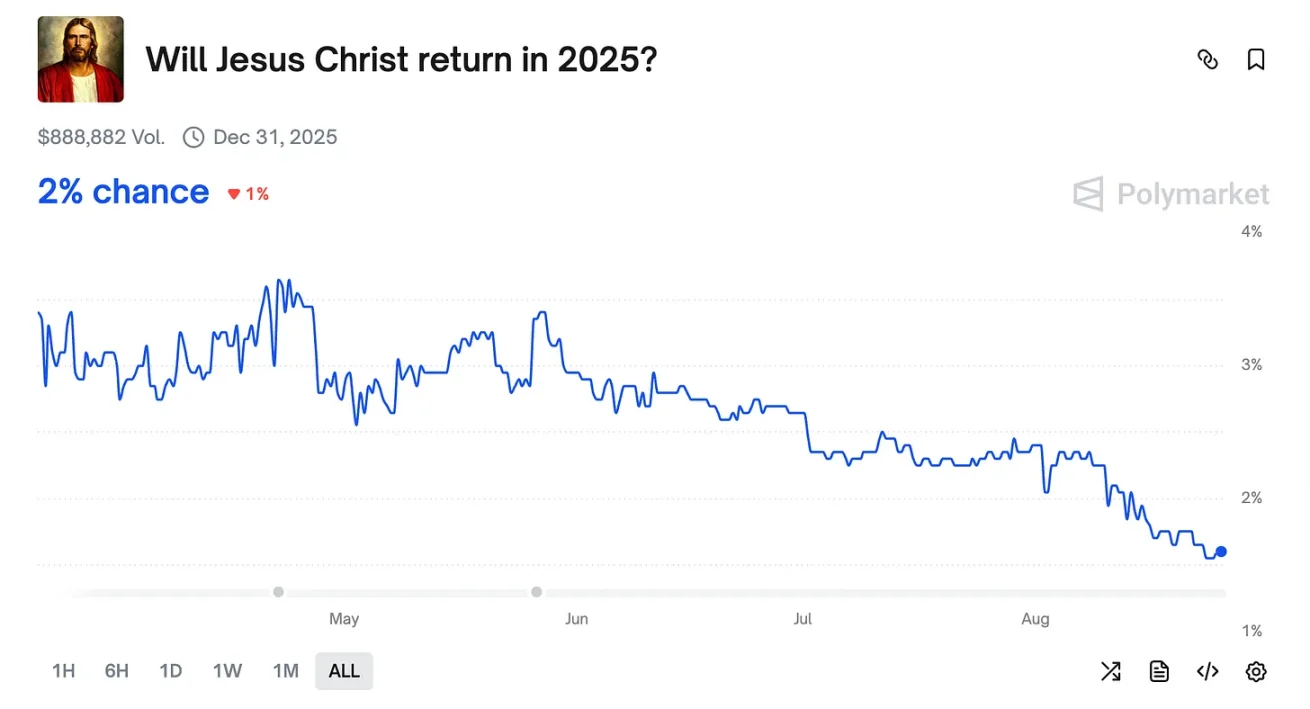

Prediction markets are now approaching major creators, proposing embedding prediction markets in content, with part of trading fees flowing to creators. Twitter is set to integrate Polymarket into its feed. This fusion of attention and trading economies will be powered by crypto rails.

Music Streaming Platforms with Better Unit Economics

Spotify pays roughly $0.005–$0.03 per stream, partly to keep subscription costs low. Letting creators issue and earn royalties from digital collectibles could improve this. For example, I’d love to own a signed vinyl copy of Fort Minor’s *The Rising Tied*.

A model might exist where vinyl is issued on-chain and redeemable offline. Such models already appear in niches—you can buy card packs from Courtyard, but social or streaming elements remain isolated.

This isn’t to say financial infrastructure doesn’t matter. We keep discussing revenue-generating apps like Hyperliquid and Jupiter for a reason—they’re today’s “Medici Banks.” Concentrated capital allows testing new tools and capturing attention.

But for sustainable growth, we need products people return to even without “betting.” Trading must transcend pure speculation.

All this makes me ask: what is culture?

It’s the shared stories we cherish: swapping Pakistani songs with a taxi driver on your way home; saving a Kheer recipe on Instagram because someone you love said her mom made it when she was sick; recommending Bollywood films like *Jab We Met*, *Veer Zaara*, or *Laapatha Ladies* because they represent the culture to you.

No money changes hands in these moments, yet a shared “base layer” of stories and emotions binds us. That sense of belonging makes things priceless. These fleeting expressions give depth to life—they’re core to my identity. Such transient moments enrich everything else, and this sentiment can be embedded in products.

Staring at Apple products long enough, you trace back to Steve Jobs’ time at Disney; holding an iPhone, you feel his desire to “build great things.” These details make people buy iOS products year after year, despite minimal changes.

Web3 products rarely scale such “base layers.” Web2 products were intentional: Facebook launched without a points program, focusing instead on Ivy League grads as a base layer; Quora was once the best place to hear insights from Silicon Valley developers; Substack remains a top spot for quality content. Web3 products have their own base layers too.

Stare long enough at Pump.fun’s feed or Polymarket discussions, and you’ll see a nascent culture forming—but like any emerging field, it struggles to take root.

Remember when I said the internet turned love letters into effortless messages? It also revolutionized how people find love—40% of couples met online in 2023. Ironically, this highlights technology’s role: it alters how we express ourselves while increasing the chance of random beautiful encounters.

If we cling to “crypto is only about speculative apps,” we’ll miss those potential serendipitous joys.

Perhaps it’s time to see crypto as a medium of expression. Perhaps it’s time to envision a new culture for our industry.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News