Nobel Prize Economist Reveals the "Crisis Structure" of "Stablecoin Legislation"

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Nobel Prize Economist Reveals the "Crisis Structure" of "Stablecoin Legislation"

Fake barriers, real traps.

By: Daii

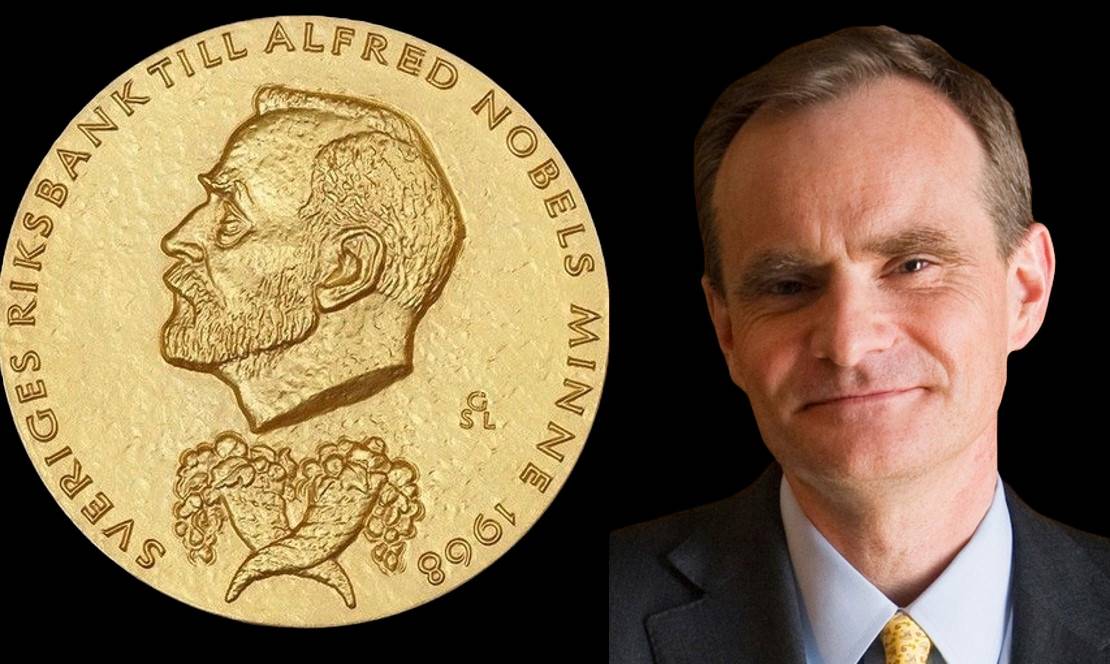

But this time, the warning comes from Simon Johnson—a scholar who just won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2024. This means his views carry substantial weight in both academic and policy circles, making them impossible to ignore.

Simon Johnson previously served as Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), focusing extensively on global financial stability, crisis prevention, and institutional reform. In the fields of macro-finance and institutional economics, he is among the few voices capable of shaping academic consensus and influencing policy design.

In early August this year, he published an article titled "The Crypto Crises Are Coming" on Project Syndicate, a globally renowned commentary platform. Often described as the "column for global thought leaders," it regularly supplies content to over 500 media outlets across more than 150 countries, with contributors including heads of state, central bank governors, Nobel laureates, and top scholars. In short, opinions published here often reach decision-makers at the highest levels worldwide.

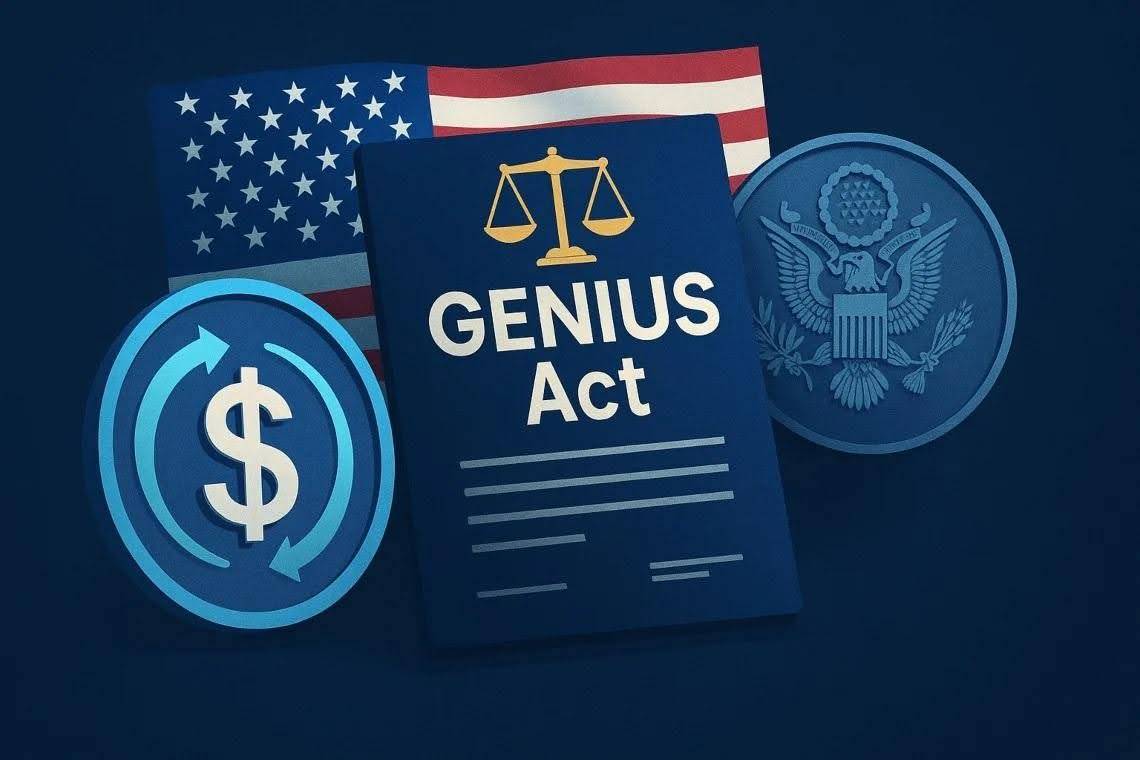

In the article, Johnson targets recent U.S. crypto legislation, particularly the recently passed GENIUS Act and the proposed CLARITY Act. In his view, these bills ostensibly aim to establish regulatory frameworks for stablecoins and other digital assets, but in reality use legislation to loosen critical constraints. (Project Syndicate)

He states bluntly:

Unfortunately, the crypto industry has acquired so much political power – primarily through political donations – that the GENIUS Act and the CLARITY Act have been designed to prevent reasonable regulation. The result will most likely be a boom-bust cycle of epic proportions.

Translation: Unfortunately, the cryptocurrency industry has gained immense political influence through extensive political donations, such that the design of the GENIUS Act and CLARITY Act aims precisely to block sensible regulation. The outcome will likely be an unprecedented boom-and-bust cycle.

At the end of the article, he delivers a stark conclusion:

The US may well become the crypto capital of the world and, under its emerging legislative framework, a few rich people will surely get richer. But in its eagerness to do the crypto industry's bidding, Congress has exposed Americans and the world to the real possibility of the return of financial panics and severe economic damage, implying massive job losses and wealth destruction.

Translation: The U.S. could very well become the world’s “crypto capital,” and under this emerging legislative framework, a small number of wealthy individuals will certainly grow even richer. Yet, by rushing to serve the interests of the cryptocurrency industry, Congress has exposed Americans and the entire world to the real risk of returning financial panics and serious economic damage—meaning massive job losses and widespread wealth erosion.

So how exactly does Johnson build his argument and logic chain? Why does he arrive at such conclusions? This is precisely what we’ll unpack next.

1. Does Johnson’s Warning Hold Water?

Johnson first sets the stage: The GENIUS Act was officially signed into law on July 18, 2025, while the CLARITY Act passed the House on July 17 and awaits Senate review.

These two bills define at the federal level—what constitutes a stablecoin, who can issue it, who regulates it, and within which scope it operates—effectively opening institutional channels for broader and deeper crypto activities. (Congress.gov)

Johnson’s subsequent risk analysis stems directly from this “institutional one-two punch.”

1.1 Spread: The Profit Engine for Stablecoin Issuers

His first step focuses on the core question—where does the money come from? For holders, stablecoins are interest-free liabilities (holding one USDC earns no interest); issuers, however, invest reserves into income-generating assets and profit from the spread. This isn’t speculation—it’s explicitly stated in terms and financial reports:

USDC terms clearly state: “Circle may allocate reserves to interest-bearing or otherwise income-generating instruments; these returns do not belong to holders.” (Circle)

Media reports and financial disclosures further confirm: Circle’s revenue relies almost entirely on reserve interest (nearly all 2024 revenue came from this source), and changes in interest rates significantly affect profitability. This implies that, as long as regulations allow and redemption expectations remain intact, issuers have inherent incentives to maximize asset-side returns. (Reuters, Wall Street Journal)

In Johnson’s view, this “spread-driven” model is structural and normalized—when profits hinge on maturity and risk premiums, and returns aren’t shared with holders, the impulse to pursue higher-yielding assets must be restrained by rules.

The problem is, those rule boundaries themselves contain flexibility.

1.2 Rules: The Devil Is in the Details

He then dissects technical clauses in the GENIUS Act, pointing out several seemingly minor details that could fundamentally alter system dynamics during times of stress:

-

Whitelist Reserves: Section 4 requires 1:1 backing limited to cash / central bank deposits, insured deposits, U.S. Treasuries with maturities ≤93 days, (reverse) repos, and government money market funds (MMFs) investing solely in these assets. While appearing robust, this still permits certain maturity and repo structures—under stress, this may necessitate “selling bonds to redeem.” (Congress.gov)

-

“Not Exceeding” Regulatory Cap: The bill authorizes regulators to set capital, liquidity, and risk management standards, but explicitly requires they “do not exceed… sufficient to ensure the ongoing operations” of the issuer. To Johnson, this compresses safety buffers down to the bare minimum needed for continuity, rather than reserving redundancy for extreme scenarios. (Congress.gov)

He argues: Under normal conditions, the whitelist plus minimal requirements make the system more efficient; but under extreme stress, maturity and repo chains amplify the time lag and price impact between “redemption” and “asset liquidation.”

1.3 Speed: Bankruptcy Measured in Minutes

Third, he brings “time” into sharp focus.

The GENIUS Act codifies stablecoin holders’ priority in bankruptcy proceedings and mandates courts strive to issue distribution orders within 14 days—appearing investor-friendly. But compared to blockchain-level redemptions occurring in minutes, this remains too slow. (Congress.gov)

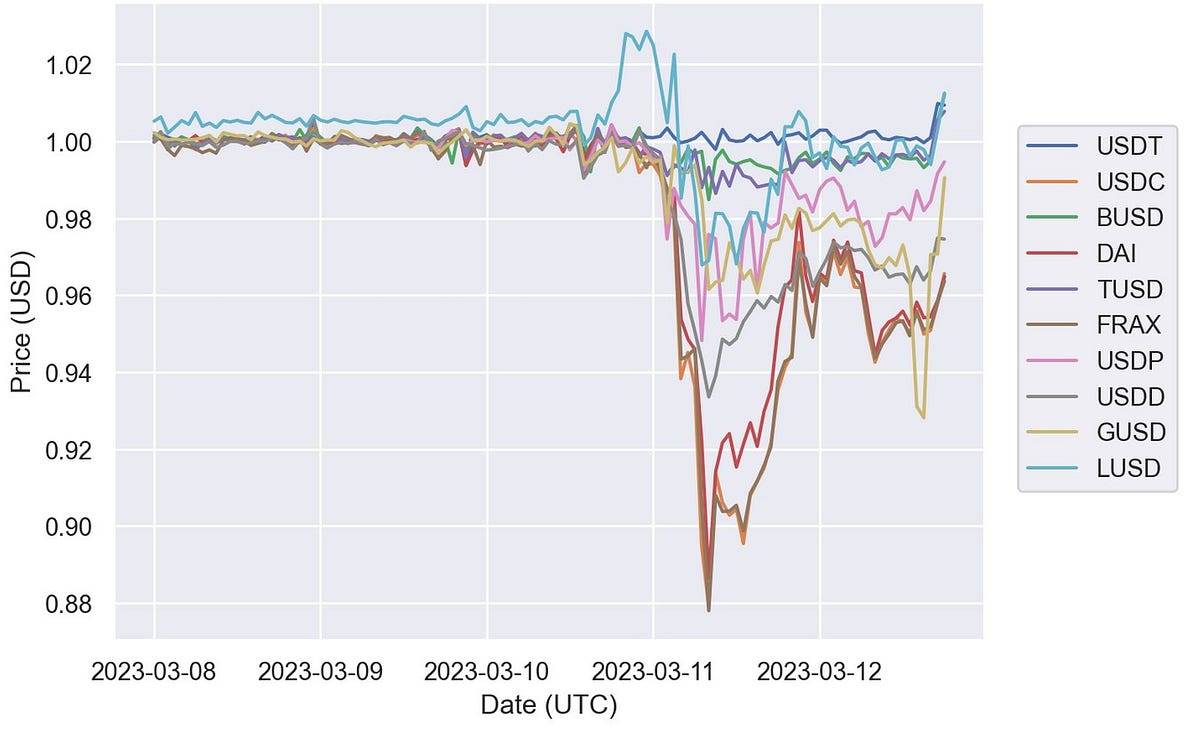

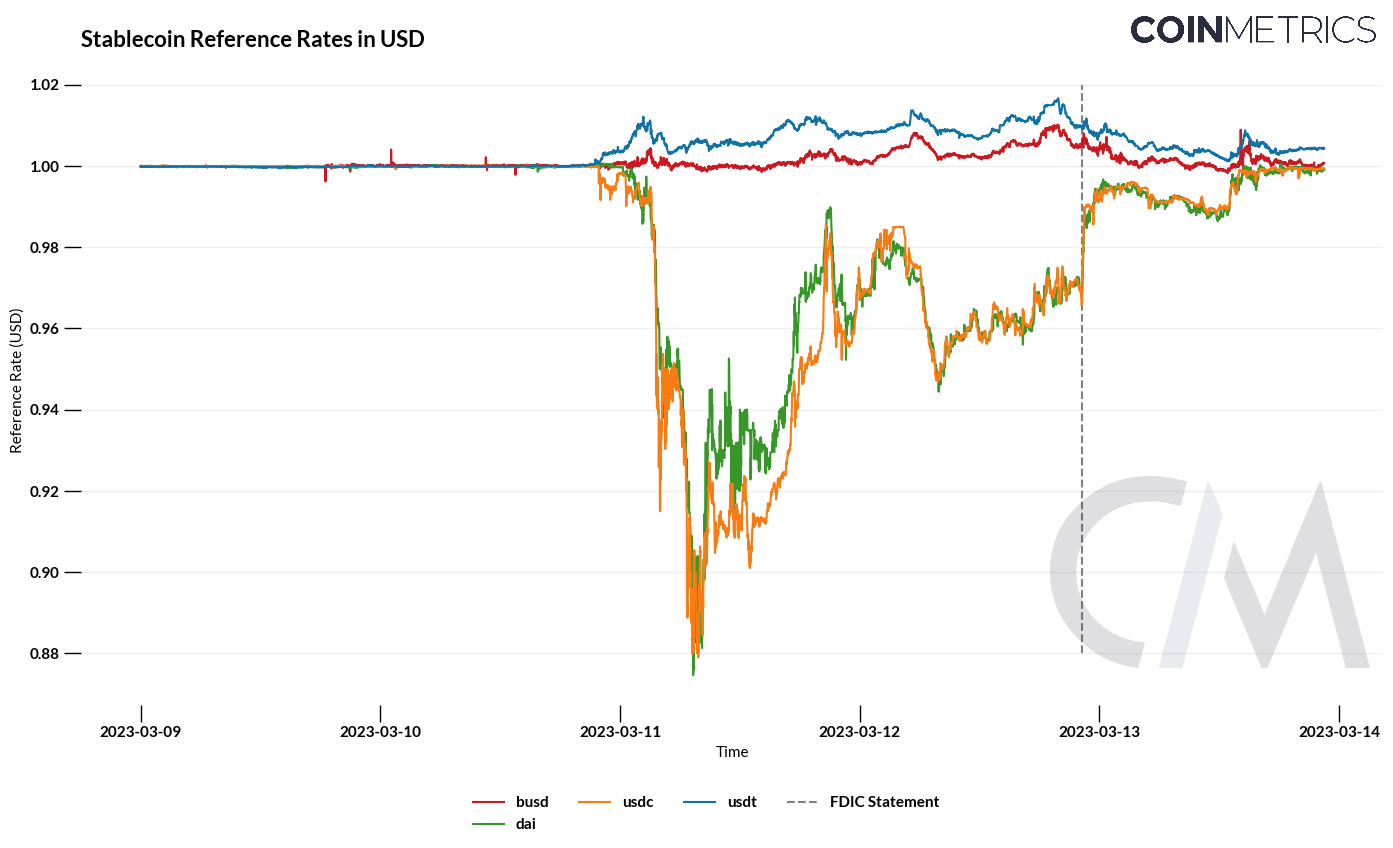

Real-world cases confirm this mismatch: During the March 2023 SVB (Silicon Valley Bank) crisis, USDC briefly dropped to $0.87–0.88, only stabilizing after reserve gaps were filled and redemptions restored; New York Fed research documents patterns of “mass stablecoin redemption” and “flight to safety” in May 2022. In short, panic and redemption unfold on an hourly basis, while legal processes operate on a daily scale. (CoinDesk, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Liberty Street Economics)

This, Johnson says, is the system’s “leverage point”: When asset-side liquidation via “selling bonds” must respond to minute-by-minute liability flight, any procedural delay can magnify individual risks into systemic shocks.

1.4 Backdoor: Where Profits Love to Roam

He then turns to cross-border dimensions:

The GENIUS Act allows foreign issuers under “comparable regulation” to sell in the U.S., provided they maintain adequate U.S. liquidity, though Treasury may waive some requirements via mutual recognition agreements. While the text doesn’t explicitly permit investment in non-dollar sovereign debt, Johnson warns that “comparable” doesn’t mean “identical,” and loosened mutual recognition or reserve location rules could let some reserves drift from dollar pegs—amplifying currency mismatch risks during sharp dollar appreciation. (Congress.gov, Gibson Dunn, Sidley Austin)

Meanwhile, the bill leaves wide room for state-qualified issuers, with federal intervention subject to conditions—creating fertile ground for regulatory arbitrage. Issuers will naturally migrate to the most lenient jurisdictions. (Congress.gov)

The conclusion: Cross-border and interstate regulatory patchwork, once combined with profit motives, tends to push risks toward the weakest seams.

1.5 Fatal: No ‘Lender of Last Resort,’ and Loose Political Constraints

Institutionally, the GENIUS Act does not establish a “lender of last resort” or insurance backstop for stablecoins. It excludes stablecoins from commodity definitions, yet stops short of classifying them as insured deposits—which would require issuers to be insured depository institutions. As early as 2021, the PWG (President’s Working Group on Financial Markets) recommended limiting stablecoin issuance to insured depository institutions to mitigate runs, but this proposal was not adopted. This means stablecoin issuers lack FDIC insurance and cannot access discount window support during crises—creating a clear gap from traditional “bank-style prudential frameworks.” (Congress.gov, U.S. Department of the Treasury)

What worries Johnson more is the potential entrenchment of these institutional gaps due to political economy factors. Recently, the crypto industry’s influence in Washington has surged—super PACs like Fairshake raised over $260 million in the 2023–24 election cycle alone, becoming one of the loudest financial backers; total external fundraising for congressional elections now exceeds the billion-dollar mark. In this environment, legislative “flexibility choices” and political incentives may reinforce each other, turning the “bare-minimum” safety buffer into both a current norm and a long-term fixture. (OpenSecrets, Reuters)

1.6 Logic: From Legislation to Bust

Linking these elements together forms Johnson’s reasoning chain:

-

A. Legislation legitimizes larger-scale stablecoin activity

-

→ B. Issuers rely on zero-interest liabilities paired with interest-bearing assets for profit

-

→ C. Legal provisions adopt “bare-minimum” standards for reserves and oversight, retaining arbitrage and mutual recognition flexibility

-

→ D. During a run, minute-level redemptions meet day-level resolution, forcing bond sales that shock short-end rates and repo markets

-

→ E. If combined with foreign currency exposure or weakest-regulation frontiers, risks escalate further

-

→ F. Absence of lender of last resort and insurance makes individual imbalances prone to sector-wide volatility

This logic is persuasive because it combines close reading of legal texts (e.g., “do not exceed… ongoing operations,” “14-day distribution order”) with empirical evidence (USDC dropping to 0.87–0.88, 2022 mass stablecoin redemptions), aligning closely with longstanding concerns from FSB (Financial Stability Board), BIS (Bank for International Settlements), and PWG about “runs and fire sales” since 2021. (Congress.gov, CoinDesk, Liberty Street Economics, Financial Stability Board)

1.7 Summary

Johnson does not claim “stablecoins will inevitably trigger systemic crisis,” but warns that when “spread incentives + minimal safety buffers + regulatory arbitrage/mutual recognition flexibility + slow resolution speed + no LLR/insurance” combine, institutional flexibility can reverse into a risk amplifier.

In his view, certain institutional choices in the GENIUS/CLARITY Acts make these conditions more likely to coexist—hence his “boom-bust” warning.

Two historical events related to stablecoins seem to indirectly validate his concerns.

2. The “Truth Moment” of Risk

If Johnson’s earlier analysis represents “institutional unease,” then the true test of the system occurs the moment a run begins—the market gives no warning and allows no time to react.

Two historically distinct events help reveal the “bottom line” of stablecoins under pressure.

2.1 Run Mechanics

First, consider UST from the “wild west era.”

In May 2022, algorithmic stablecoin UST rapidly lost its peg over several days. Associated token LUNA entered a death spiral, the Terra chain halted temporarily, exchanges delisted en masse, and the entire ecosystem lost approximately $40–45 billion in market value within a week, triggering a wider crypto sell-off. This wasn’t ordinary price fluctuation, but a classic bank-style run: When “stability” depends on protocol-based minting/burning and confidence loops, rather than quickly redeemable, high-liquidity external assets, a broken promise leads to self-amplifying sell pressure until total collapse. (Reuters, The Guardian, Wikipedia)

Next, consider the pre-compliance-era USDC de-pegging incident, which revealed how off-chain banking risks instantly transmit onto-chain.

In March 2023, Circle disclosed that around $3.3 billion in reserves were held at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), which suddenly faced a liquidity crisis. Within 48 hours, USDC traded as low as $0.88 on secondary markets. Only after regulators announced full deposit protection and launched the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program) emergency tool did market sentiment rapidly reverse and the peg restore.

That week, Circle reported $3.8 billion in net redemptions; third-party data showed sustained on-chain redemptions and destruction, peaking at nearly $740 million per day. This shows that even when reserves are invested in highly liquid assets, if the “redemption path” or “custodial bank” is questioned, runs can escalate within minutes/hours—until a clear liquidity backstop emerges. (Reuters, Investopedia, Circle, Bloomberg.com)

Comparing both events reveals two triggers for the same “run mechanics”:

-

UST: Endogenous fragility—no verifiable, quickly redeemable external assets backing the peg, relying entirely on expectations and arbitrage cycles;

-

USDC: External anchor intact, but off-chain hosting point destabilized—single-point failure on the banking side amplified instantly on-chain into price and liquidity shocks.

2.2 Action and Feedback

A New York Fed team modeled this behavior using money market fund frameworks: Stablecoins have a clear “breaking the buck” threshold. Once breached, redemptions and rebalancing accelerate, with capital fleeing from “riskier stablecoins” to those perceived safer—so-called “flight to quality.” This explains why, during the USDC de-peg, some funds simultaneously flowed into “Treasury-backed” or otherwise deemed safer alternatives—migration was rapid, directional, and self-reinforcing. (Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Liberty Street Economics)

More importantly, feedback loops emerge: When on-chain redemptions accelerate and issuers must “sell bonds to redeem,” selling pressure transmits directly into short-term Treasury and repo markets. A recent BIS working paper using daily data from 2021–2025 finds: Large inflows into stablecoins depress 3-month Treasury yields by 2–2.5 bps within 10 days; equivalent outflows exert an even stronger upward effect—2–3 times greater. In other words, stablecoins’ procyclical and countercyclical fluctuations already leave statistically detectable “fingerprints” on traditional safe assets; should a large-scale redemption akin to the USDC event occur, the transmission path of “passive selling → price impact” is real and operational. (Bank for International Settlements)

2.3 Lessons

The UST and USDC cases are not coincidences, but two structured warnings:

-

“Stability” without redeemable external assets is essentially racing against coordinated behavior;

-

Even with high-quality reserves, single-point fragility in redemption pathways gets instantly magnified on-chain;

The “time gap” between run speed and resolution speed determines whether a localized risk escalates into systemic disruption.

This is why Johnson links “stablecoin legislation” with “run mechanics”—if legislation provides only bare-minimum safety buffers, without embedding intraday liquidity, redemption SLAs (Service Level Agreements), stress testing, and orderly resolution into enforceable mechanisms, the next “truth moment” may arrive faster.

So the issue isn’t whether “legislation is wrong,” but recognizing:

Proactive legislation is clearly better than none, but reactive legislation may be stablecoins’ true rite of passage.

3. Stablecoin’s Rite of Passage—Reactive Legislation

If the financial system is likened to a highway, proactive legislation resembles installing guardrails, speed limits, and emergency lanes before driving; reactive legislation typically follows accidents, filling past gaps with thicker concrete barriers.

To understand “stablecoin’s rite of passage,” the best analogy lies in stock market history.

3.1 Stock Market’s Rite of Passage

The U.S. securities market didn’t start with disclosure rules, exchange regulations, information symmetry, or investor protections. These “guardrails” were almost entirely added post-crisis.

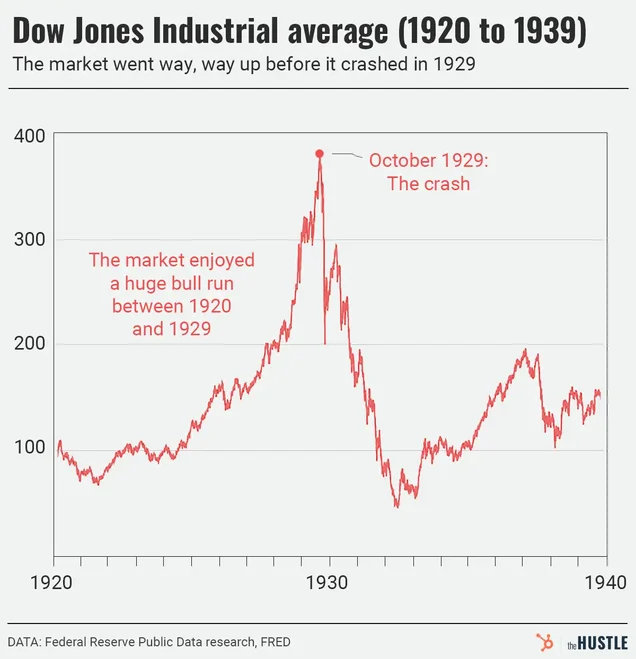

The 1929 crash plunged the Dow Jones into abyss, triggering successive bank failures, peaking in 1933. After this disaster, the U.S. passed the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, codifying disclosure and ongoing oversight, and established the SEC as a permanent regulator. In other words, stock market maturity wasn’t achieved through persuasion, but shaped by crisis—its “coming of age” was reactive legislation. (federalreservehistory.org, SEC, guides.loc.gov)

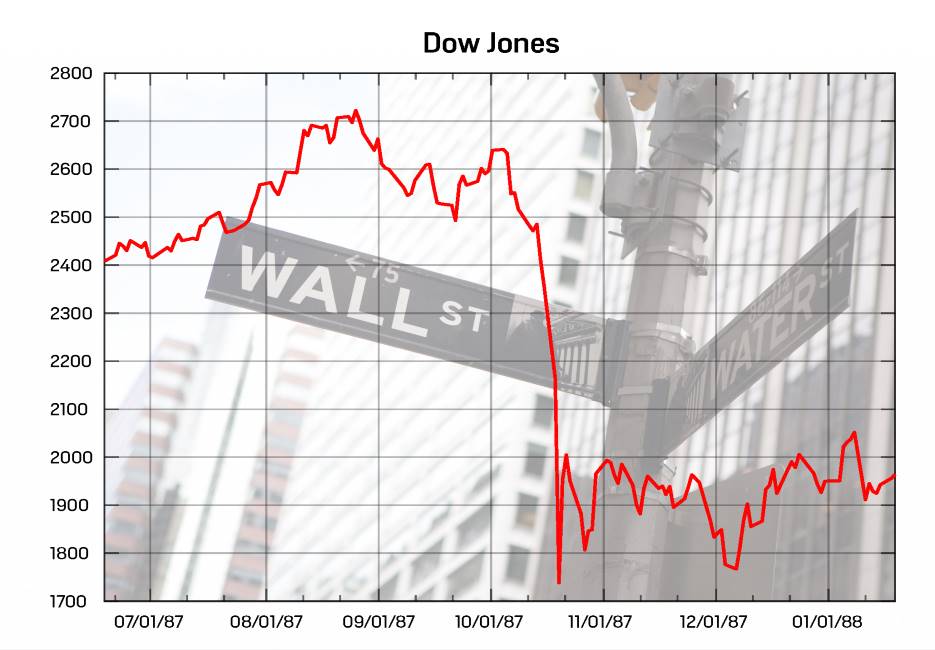

1987’s “Black Monday” is another collective memory: The Dow plunged 22.6% in a single day. Only afterward did U.S. exchanges institutionalize circuit breakers, giving markets brakes and emergency buffers. In extreme moments like 2001, 2008, and 2020, “circuit breakers” became standard tools to curb stampedes. This is classic reactive formalization—first pain, then policy. (federalreservehistory.org, Schwab Brokerage)

3.2 Stablecoins

Stablecoins are not “second-tier innovations,” but infrastructure-level innovations like stocks: Stocks transformed “ownership” into tradable instruments, reshaping capital formation; stablecoins transform “fiat cash legs” into programmable, 24/7 global settlement objects, reshaping payment and clearing. The BIS’s latest report states plainly that stablecoins are already designed as gateways into crypto ecosystems, serving as mediums of exchange on public blockchains and increasingly coupling with traditional finance—this is reality, not concept. (Bank for International Settlements)

This “real-virtual” integration is materializing.

This year, Stripe announced Shopify merchants can accept USDC payments and choose automatic settlement into local currency or direct holding in USDC—on-chain cash legs integrated directly into merchant ledgers. Visa also clearly positions stablecoins on its website as payment vehicles combining “fiat stability × crypto speed,” integrating tokenization and on-chain finance into its payment network. This means stablecoins are now embedded in real-world cash flows; once cash legs go on-chain, risks no longer stay confined to crypto circles. (Stripe, Visa Corporate)

3.3 An Inevitable Rite of Passage

From a policy perspective, why is stablecoin “reactive legislation” almost inevitable? Because it exhibits classic “gray rhino” traits:

-

Significant scale: On-chain stablecoin settlements and activity form a parallel global payment layer, capable of spillovers when failing;

-

Deepening coupling: BIS metrics show large stablecoin outflows significantly raise 3-month Treasury yields—by 2–3 times the drop caused by equivalent inflows—indicating influence on short-end pricing of public safe assets;

-

Precedents exist: The two “run case studies” of UST and USDC prove minute-scale panic can penetrate on- and off-chain boundaries.

This isn’t random black swan coincidence, but repeatable mechanics. Once a major spillover occurs, policy will inevitably strengthen safeguards—just as 1933/1934 did for stocks, and 1987 did for circuit breakers. (Bank for International Settlements)

Thus, “reactive legislation” isn’t a rejection of innovation; on the contrary, it marks innovation’s social acceptance.

When stablecoins truly fuse internet speed with central bank monetary units, they evolve from “insider tools” to “candidates for public settlement layers.” And once entering the public domain, society will, after accidents, demand rules ensuring they possess liquidity organization and orderly resolution capabilities equal to—or exceeding—those of money market funds:

-

Circuit breakers (swing pricing / liquidity fees)

-

Intraday liquidity thresholds

-

Redemption SLAs

-

Cross-border equivalent regulation

-

Minute-triggered bankruptcy priority

These paths mirror exactly how stock markets evolved: First unleash efficiency, then cement guardrails through crisis.

This isn’t regression, but stablecoin’s rite of passage.

Conclusion

If stocks came of age amid the bloodbath of 1929, anchoring “disclosure–regulation–enforcement” into institutions, then stablecoins’ coming of age means hardwiring “transparency–redemption–resolution” into code and law.

We all hope to avoid repeating the devastation of crypto crises, but history’s greatest irony is that humanity never truly learns.

Innovation is never crowned by slogans, but fulfilled by constraints—verifiable transparency, enforceable redemption promises, and pre-tested orderly resolution are the true entry tickets for stablecoins to join the public settlement layer.

If crisis is unavoidable, let it come sooner—to expose fragility early, allowing timely institutional repair. Only then can prosperity avoid ending in collapse, and innovation escape burial in ruins.

Glossary

-

Redemption: The process by which holders exchange stablecoins at par for fiat or equivalent assets. Redemption speed and pathway determine survival during a run.

-

Reserves: The asset pool (cash, central/commercial bank deposits, short-term U.S. Treasuries, (reverse) repos, government MMFs, etc.) held by issuers to ensure redemption. Composition and duration determine liquidity resilience.

-

Spread: Stablecoins are zero-interest liabilities to holders; issuers earn interest spreads by investing reserves in income-generating assets. The spread model inherently incentivizes configurations toward higher yield and longer duration.

-

(Reverse) Repo: Short-term financing/investment arrangements using bonds as collateral.

-

Government MMF: Money market funds investing exclusively in government-issued, high-liquidity assets. Often considered part of “cash equivalents,” but may face redemption pressure in extreme scenarios.

-

Insured Deposits: Bank deposits covered by deposit insurance (e.g., FDIC). Non-bank stablecoin issuers’ deposits typically lack equivalent protection.

-

Lender of Last Resort (LLR): Public liquidity backstop during crises (e.g., central bank discount window/special facilities). Absence makes individual liquidity shocks more likely to evolve into systemic sell-offs.

-

Fire Sale: Chain reaction of forced asset sales causing price overshoots, common during runs and margin liquidations.

-

Breaking the Buck: A nominally $1-stable instrument (e.g., MMF/stablecoin) trades below par, triggering cascading redemptions and flight to safety.

-

Intraday Liquidity: Ability to access or liquidate cash and equivalents within the same trading day. Determines whether “minute-level liabilities” can be matched by “minute-level assets.”

-

Service Level Agreement (SLA): Explicit commitments regarding redemption speed, limits, and response (e.g., “T+0 redeemable cap,” “queue-based processing”), helping stabilize expectations.

-

Orderly Resolution: Pre-planned distribution and liquidation of assets and liabilities upon default/bankruptcy, avoiding chaotic stampedes.

-

Equivalence/Recognition: Mechanisms where different jurisdictions recognize each other’s regulatory frameworks as “equivalent.” If “equivalent ≠ identical,” regulatory arbitrage becomes likely.

-

Buffer: Redundancy in capital, liquidity, and duration to absorb stress and uncertainty. A too-low “bare-minimum” buffer fails under extreme conditions.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News