The Tragedy of the Crypto Commons Series: Polymarket's Data Indexing Woes

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Tragedy of the Crypto Commons Series: Polymarket's Data Indexing Woes

This article focuses on one of the most prominent applications in the Ethereum ecosystem: Polymarket and its data indexing tool.

Author: shew

Abstract

Welcome to the "Tragedy of the Crypto Commons" series from the GCC Research column.

In this series, we focus on "public goods" in the crypto world—critical nodes that are gradually becoming dysfunctional. These are foundational infrastructures for the entire ecosystem, yet they often face insufficient incentives, governance imbalances, and even increasing centralization. The ideals pursued by cryptographic technology and the need for redundant stability in reality are being severely tested in these overlooked areas.

This issue centers on one of the most mainstream applications within the Ethereum ecosystem: Polymarket and its data indexing tools. Especially since the beginning of this year, events such as market manipulation around Trump's election victory, Ukraine's rare earth deals, and political bets on Zelenskyy's suit color have repeatedly brought Polymarket into the spotlight. The scale of capital and market influence it carries makes these controversies impossible to ignore.

However, is the key foundational module of this representative "decentralized prediction market"—data indexing—truly decentralized? Why has a public infrastructure like The Graph failed to fulfill its expected role? What should a truly usable and sustainable public data indexing infrastructure look like?

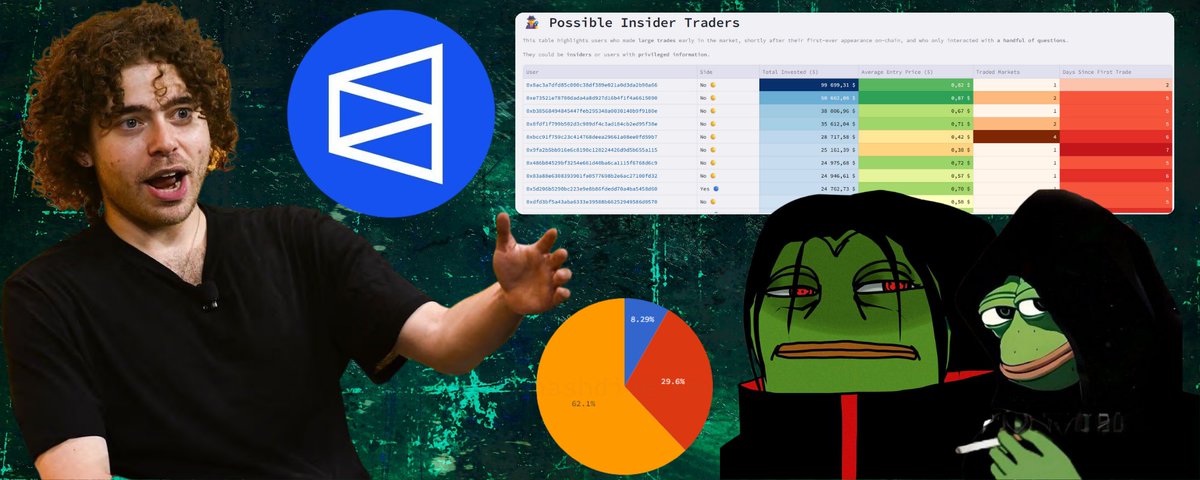

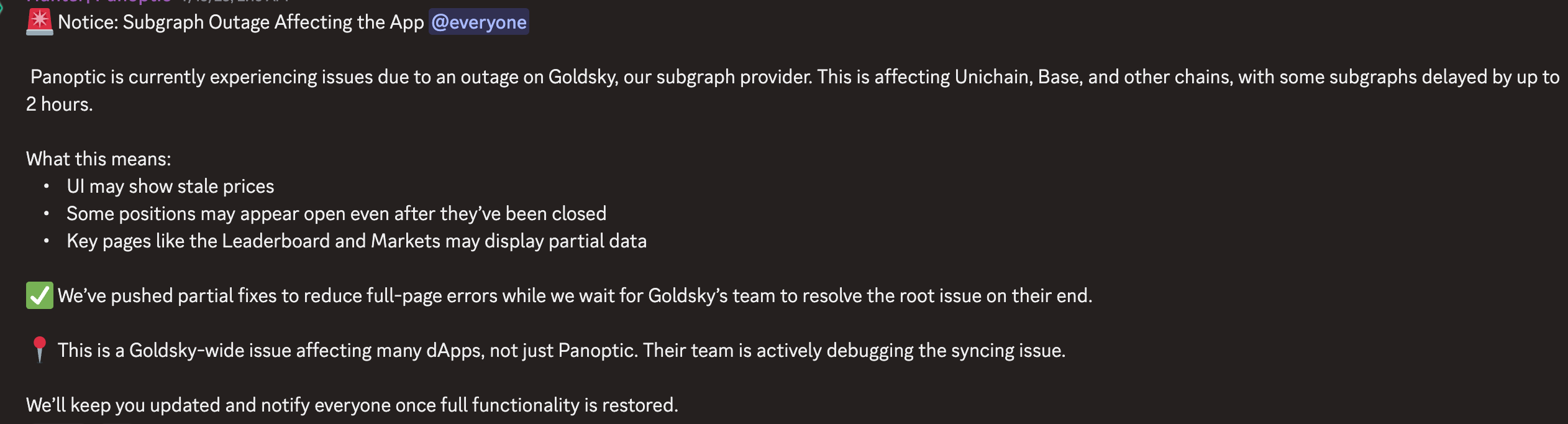

1. A Chain Reaction Triggered by the Outage of a Centralized Data Platform

In July 2024, Goldsky suffered a six-hour outage (Goldsky is a real-time blockchain data infrastructure platform for Web3 developers, offering indexing, subgraph, and streaming data services to accelerate the development of data-driven decentralized applications), causing a significant portion of projects in the Ethereum ecosystem to become paralyzed. For example, DeFi frontends could no longer display users' positions or balances, and the prediction market Polymarket failed to show accurate data. To end users, countless projects appeared completely unusable.

This should not happen in the world of decentralized applications. After all, wasn't the original purpose of blockchain technology to eliminate single points of failure? The Goldsky incident exposed an unsettling truth: although blockchains themselves are as decentralized as possible, the infrastructure used by applications built on-chain often contains heavily centralized services.

The reason lies in the fact that blockchain data indexing and retrieval fall under "non-excludable, non-rivalrous" digital public goods. Users typically expect them to be free or extremely low-cost, yet they require continuous investment in high-intensity hardware, storage, bandwidth, and operational manpower. Without a sustainable revenue model, winner-takes-all centralization emerges: once a service provider gains a first-mover advantage in speed and capital, developers tend to route all query traffic through it, recreating single-point dependencies. Projects like Gitcoin have repeatedly emphasized, "Open-source infrastructure can create billions in value, yet its creators often can't afford their mortgage."

This reminds us that the decentralized world urgently needs public good funding, redistribution, or community-driven initiatives to diversify Web3 infrastructure; otherwise, centralization issues will persist. We call on DApp developers to build locally-first products and urge the technical community to consider the failure of data retrieval services during DApp design, ensuring users can still interact with projects even without such infrastructure.

2. Where Does the Data You See in DApps Come From?

To understand why incidents like Goldsky occur, we must delve into the behind-the-scenes mechanics of DApps. For ordinary users, DApps usually consist of two parts: on-chain contracts and front-end interfaces. Most users are accustomed to using tools like Etherscan to check on-chain transaction status and obtain necessary information via the front end while initiating transactions through the front end. But where exactly does the data displayed on the front end come from?

Indispensable Data Retrieval Services

Suppose you're building a lending protocol that needs to display users' positions along with each position’s margin and debt status. A naive approach would be for the front end to read this data directly from the chain. However, in practice, lending protocol contracts do not allow querying position data via user address. Instead, they provide functions to query specific data using a position ID. So, to display a user's positions on the front end, we’d need to retrieve all existing positions and then identify which belong to the current user. This is akin to asking someone to manually search millions of pages of ledgers for specific information—technically feasible but extremely slow and inefficient. In fact, front ends struggle to complete such retrieval tasks; even large DeFi projects may take several hours to execute data queries directly on servers using local nodes.

Therefore, we must introduce infrastructure to accelerate data access. Companies like Goldsky provide these data indexing services. The image below illustrates the types of data indexing services can deliver to applications.

Here, some readers might wonder whether TheGraph, a seemingly decentralized data retrieval platform in the Ethereum ecosystem, has any relation to Goldsky, and why so many DeFi projects use Goldsky instead of the more decentralized TheGraph as their data provider.

The Relationship Between TheGraph / Goldsky and SubGraph

To answer these questions, we first need to understand a few technical concepts.

-

SubGraph is a development framework allowing developers to write code that reads and aggregates on-chain data and presents it to the front end.

-

TheGraph is an early decentralized data retrieval platform that developed the SubGraph framework using AssemblyScript. Developers can use the subgraph framework to capture contract events and write them into databases, then query the data via GraphQL or directly access the database using SQL.

-

We generally refer to service providers running SubGraphs as SubGraph operators. Both TheGraph and Goldsky are actually SubGraph hosts. Since SubGraph is only a development framework, the programs built with it must run on servers. As shown in Goldsky’s documentation:

Some readers may wonder why there are multiple SubGraph operators?

This is because the SubGraph framework merely defines how data is read from blocks and written into databases.

It does not specify how data flows into the SubGraph program or which type of database stores the final output—these aspects are implemented independently by each SubGraph operator.

Typically, SubGraph operators implement optimizations like node modifications for faster performance, leading to different strategies and technical approaches among operators such as TheGraph and Goldsky.

TheGraph currently uses the Firehose solution, enabling faster data retrieval than before, whereas Goldsky has not open-sourced the core program powering its SubGraph operations.

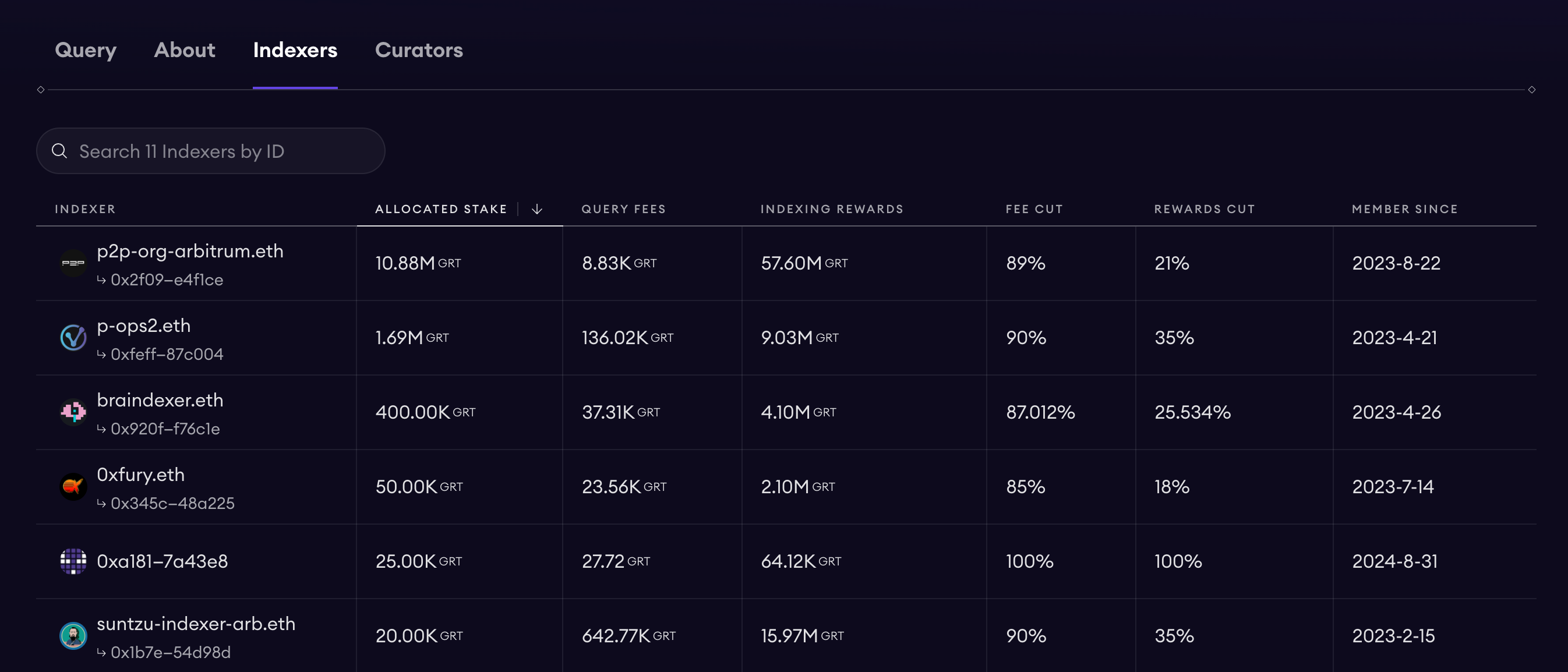

As mentioned earlier, TheGraph is a decentralized data retrieval platform. Take the Uniswap v3 subgraph as an example—we see numerous operators providing data retrieval services for Uniswap v3. Thus, we can view TheGraph as an integrated platform of SubGraph operators: users submit their SubGraph code to TheGraph, and internal operators assist in data retrieval.

Goldsky’s Pricing Model

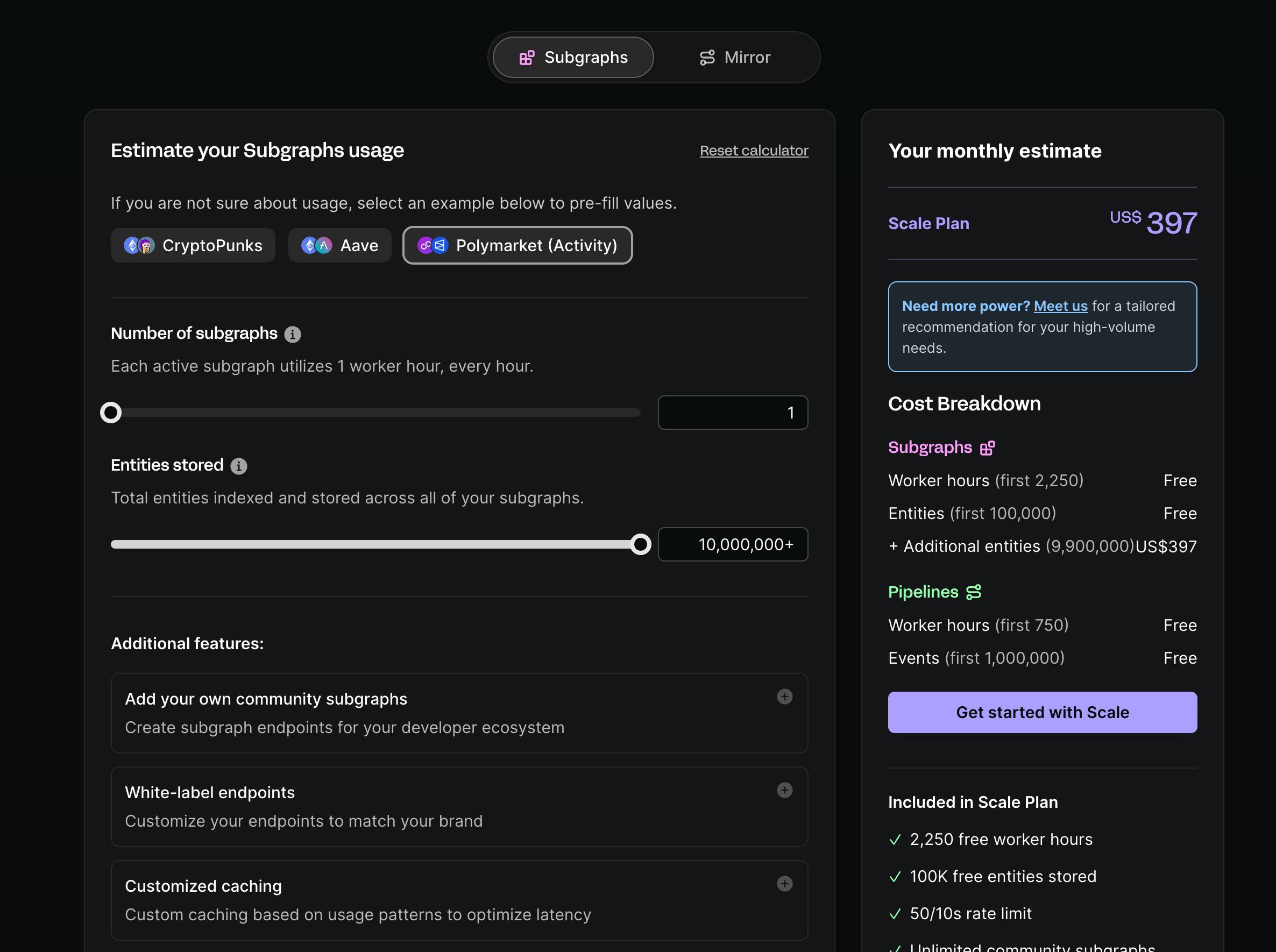

For centralized platforms like Goldsky, billing follows a simple resource-based pricing scheme—the most common SaaS model on the internet, familiar to most technical personnel. The image below shows Goldsky’s price calculator:

TheGraph’s Pricing Model

TheGraph employs a fee structure entirely different from conventional models—one tied to GRT’s tokenomics. The image below illustrates GRT’s overall token economics:

-

Whenever a DApp or wallet sends a request to a Subgraph, the Query Fee is automatically split: 1% burned, ~10% routed to the Subgraph’s curation pool (Curator/developer), and the remaining ~89% distributed via exponential rewards to Indexers and their Delegators providing computational power.

-

An Indexer must self-stake ≥100k GRT to go online; delivering incorrect data results in penalties (slashing). Delegators stake GRT to Indexers and receive a proportional share of the ~89% reward.

-

Curators (typically developers) signal their commitment by staking GRT on their Subgraph’s bonding curve. Higher Signal values attract more Indexers to allocate resources. Community experience suggests raising 5k–10k GRT ensures multiple Indexers participate. Meanwhile, curators also earn the 10% royalty.

TheGraph’s Per-Query Fees:

Register an API KEY in TheGraph’s backend and use it to request data from operators within TheGraph. These requests are charged per query, requiring developers to pre-deposit GRT tokens on the platform to cover API costs.

TheGraph’s Signal Staking Fees:

For SubGraph deployers needing operators on TheGraph to retrieve data, the revenue-sharing mechanism requires signaling that their query service is superior and thus worth higher returns. This involves staking GRT—similar to advertising and guaranteeing profitability—to attract participation. During testing, developers can freely deploy SubGraphs to TheGraph, where official resources provide limited free queries unsuitable for production. Once satisfied with test performance, developers can publish to the public network and wait for other operators to join. Developers cannot pay a specific operator directly for guaranteed retrieval but must incentivize multiple operators competitively to avoid single-point dependency. This process requires curating (or signaling) their SubGraph by staking a certain amount of GRT. Only when staked GRT reaches a threshold (previously reported as 10,000 GRT) do operators begin retrieving data for the SubGraph.

Poor Billing Experience: A Hurdle for Developers and Traditional Accountants

For most project developers, using TheGraph is relatively cumbersome. While purchasing GRT tokens is manageable for Web3 projects, the process of curating a deployed SubGraph and waiting for operator participation is highly inefficient. This step faces at least two issues:

-

Uncertainty in staking quantity and operator onboarding time. When I previously deployed a SubGraph, I had to consult TheGraph’s community ambassador to determine the required GRT amount. For most developers, this data isn’t readily available. Additionally, even after sufficient staking, it takes time for operators to begin retrieval.

-

Complexity in cost accounting and financial reporting. TheGraph’s tokenomic-based fee design complicates cost calculations for most developers. A more practical issue arises when businesses attempt to account for these expenses—accountants may struggle to understand the cost structure.

"Well, Maybe Centralization Is Better?"

Clearly, for most developers, choosing Goldsky directly is simpler. Its pricing is universally understandable, and payment ensures near-immediate availability, drastically reducing uncertainty. This has led to widespread reliance on a single product for blockchain data indexing and retrieval.

Evidently, TheGraph’s complex GRT tokenomics hinder its broad adoption. Tokenomics can be complex, but such complexity should not be exposed to users. For instance, the GRT curation staking mechanism should not burden end users; TheGraph would be better off offering a simplified payment interface.

This critique of TheGraph is not my personal opinion alone. Paul Razvan Berg, renowned smart contract engineer and founder of Sablier, expressed similar views in a tweet, stating that the SubGraph deployment and GRT billing user experience is extremely poor.

3. Existing Solutions

Regarding solutions to single-point failures in data retrieval, we’ve already touched on one: developers can consider using TheGraph, though the process is more complex, requiring GRT purchases for staking, curation, and API fees.

Currently, the EVM ecosystem hosts numerous data retrieval tools. Refer to Dune’s The State of EVM Indexing or rindexer’s EVM Data Retrieval Tools Overview for details. Another recent discussion can be found in this tweet.

This article won’t analyze the root cause of Goldsky’s outage, as Goldsky knows the specifics but only discloses them to enterprise users. This means third parties currently cannot know exactly what went wrong. Based on their report, the issue may have involved problems writing retrieved data into the database. In this brief report, Goldsky mentioned the database became inaccessible and was only restored through collaboration with AWS.

In this section, we mainly introduce alternative solutions:

-

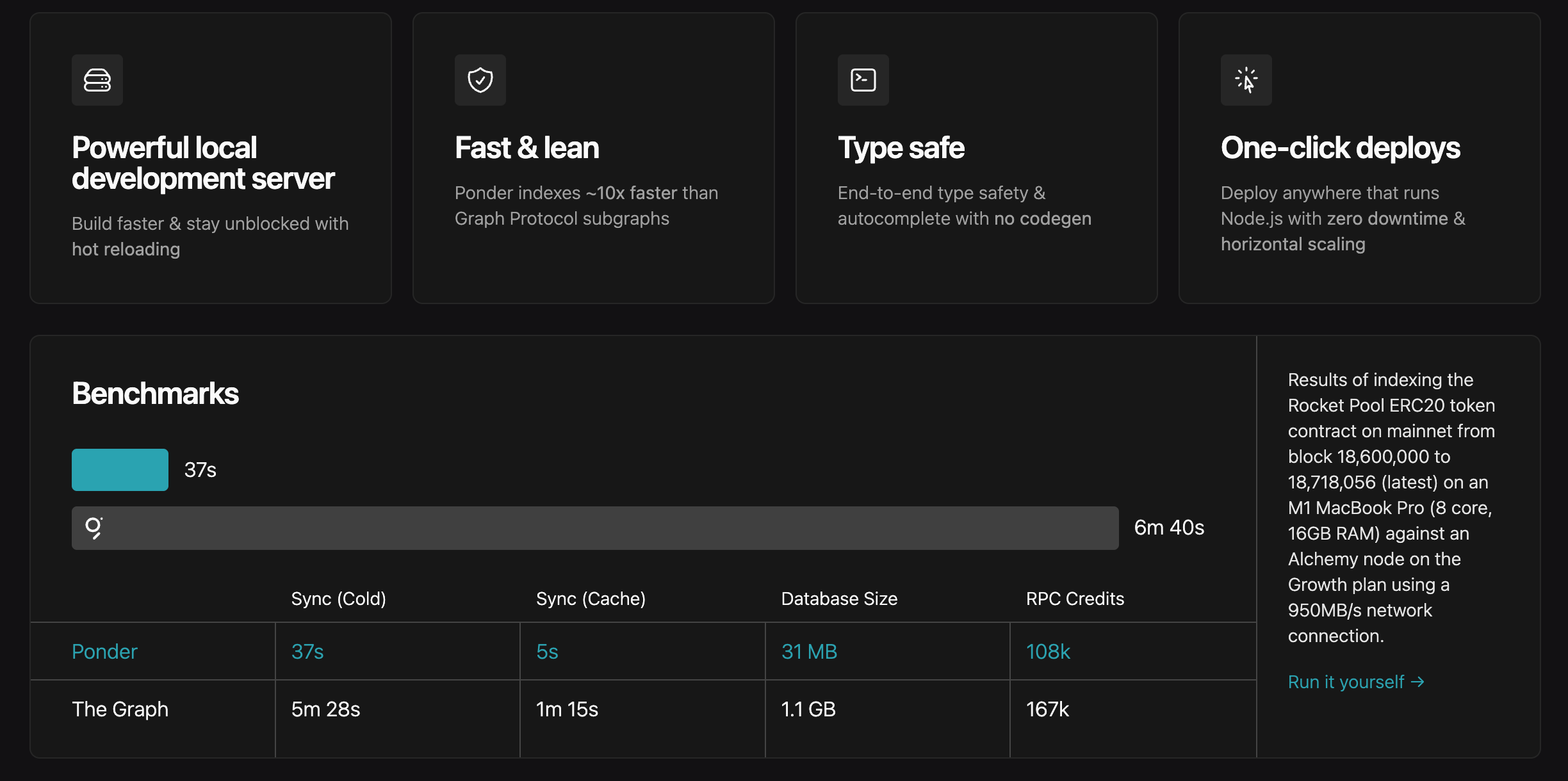

Ponder is a simple, developer-friendly, and easy-to-deploy data retrieval tool that developers can host on self-rented servers.

-

Local-first is an intriguing development philosophy advocating that users maintain a good experience even without network connectivity. With blockchains, we can somewhat relax local-first constraints, ensuring a good experience whenever users can connect to the blockchain.

Ponder

Why do I recommend ponder over other tools? Key reasons include:

-

Ponder has no vendor dependency. Initially built by an individual developer, unlike enterprise-provided tools, ponder only requires users to input an Ethereum RPC URL and a PostgreSQL database connection.

-

Ponder offers excellent developer experience. Having used it multiple times, I find its TypeScript foundation and primary reliance on viem make development smooth and efficient.

-

Ponder delivers higher performance.

Certainly, there are drawbacks. Ponder is still under rapid development, so developers might encounter breaking changes that prevent older projects from running. As this article isn’t a technical tutorial, we won’t dive deeper into ponder’s development details—readers with technical backgrounds can refer to the documentation.

A more interesting aspect is ponder’s nascent commercialization, which aligns well with the "separation theory" discussed in a previous article.

Here, we briefly introduce "separation theory." Public goods, due to their non-excludability, serve unlimited users. Charging for them risks excluding some users, resulting in suboptimal social welfare (in economic terms, "not Pareto optimal"). Theoretically, public goods could use differential pricing, but the cost of implementing such pricing likely exceeds the surplus gained. Hence, public goods remain free—not because they should inherently be free, but because fixed fees harm social welfare, and no cheap method exists for personalized pricing. Separation theory proposes a way to price within public goods: isolate a homogeneous user segment and charge them. Crucially, it doesn’t block free access for others but creates a mechanism to charge a subset.

Ponder applies separation theory similarly:

-

Deploying ponder requires technical knowledge, including setting up external dependencies like RPC and databases.

-

After deployment, ongoing maintenance is needed—for example, using proxy systems for load balancing to prevent data requests from interfering with background chain data retrieval. These tasks are slightly complex for average developers.

-

Ponder is currently beta-testing a fully automated deployment service, marble, where users simply submit code for automatic deployment.

This clearly applies separation theory: developers unwilling to self-host and maintain ponder are isolated and can pay for simplified deployment. Of course, marble’s emergence doesn’t affect other developers’ ability to freely use and self-host the ponder framework.

Ponder vs. Goldsky audiences?

-

Ponder, with zero vendor dependency, is more popular than vendor-dependent tools for small-scale projects.

-

Developers of large-scale projects may not choose ponder, as they often demand high-performance retrieval services, which providers like Goldsky better guarantee.

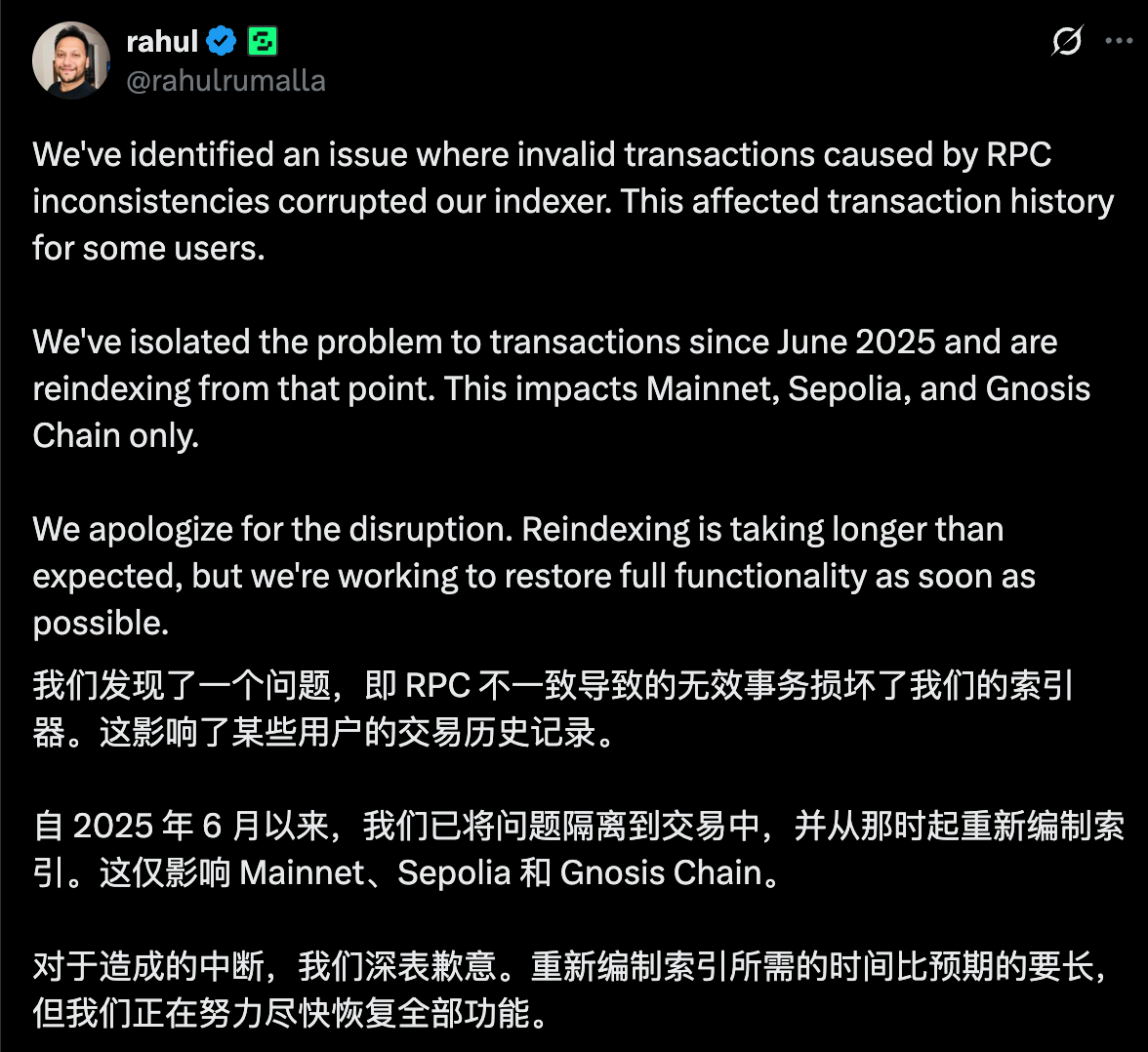

Both carry risks. Given the recent Goldsky outage, developers are advised to maintain their own ponder instance to handle potential third-party service failures. Additionally, when using ponder, consider the validity of RPC responses—a recent incident reported by Safe involved an indexer crash due to invalid RPC data. While there's no direct evidence linking this to the Goldsky event, I suspect Goldsky may have faced a similar issue.

Local-First Development Philosophy

Local-first has been a topic of discussion over recent years. Simply put, local-first software should have:

-

Offline functionality

-

Cross-client collaboration

Most technical discussions around local-first involve CRDT (Conflict-free Replicated Data Type) technology—an approach using conflict-free data formats that automatically merge changes across devices to maintain integrity. One way to view CRDTs is as data types with simple consensus protocols, ensuring data consistency in distributed environments.

However, in blockchain development, we can relax some local-first requirements. We only require that, in the absence of backend indexing data provided by project developers, users retain minimal usability on the frontend. Moreover, blockchain itself already solves cross-client synchronization.

In DApp contexts, local-first principles can be implemented as follows:

-

Cache critical data: Frontends should cache essential user data like balances and positions, allowing users to see the last known state even if indexing services fail.

-

Implement degraded functionality: When backend indexing fails, DApps can offer basic features—e.g., directly reading some data from the chain via RPC to ensure users see updated information.

This local-first DApp design significantly enhances application resilience, preventing total failure when indexing services collapse. Ignoring usability, the ideal local-first app would require users to run a local node and use tools like trueblocks for local data retrieval. For further discussion on decentralized or local retrieval, see the tweet Literally no one cares about decentralized frontends and indexers.

4. Final Thoughts

The six-hour Goldsky outage sounded an alarm for the ecosystem. While blockchains themselves are decentralized and resistant to single points of failure, the application ecosystems built atop them remain highly dependent on centralized infrastructure services. This dependence introduces systemic risk.

This article briefly explained why TheGraph, despite its reputation, isn’t widely adopted today, particularly highlighting the complexities introduced by GRT tokenomics. Finally, we discussed ways to build more robust data retrieval infrastructure. We encourage developers to adopt ponder’s self-hosted data retrieval framework as an emergency option and commend its sound commercialization path. We also advocate for the local-first development philosophy, urging developers to build applications that remain functional even without data retrieval services.

Currently, many Web3 developers are aware of the single-point failure risks in data retrieval services. GCC hopes more developers will pay attention to this infrastructure, experiment with decentralized data retrieval solutions, or design frameworks enabling DApp frontends to function without such services.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News