a16z Partner: Keep Companies on Track with an Operating Plan for Success

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

a16z Partner: Keep Companies on Track with an Operating Plan for Success

An operating plan might not sound glamorous, but it is one of the most controllable and usable tools at your disposal.

Author: Emily Westerhold, Partner at a16z crypto

Translation: Luffy, Foresight News

"If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail." Benjamin Franklin didn't say this with startup founders in mind, but it certainly applies. Founders—especially those in crypto—have far too many things beyond their control: volatile markets, shifting regulations, and sky-high external expectations.

That’s why focusing on what you *can* control is so critical—and that’s where an operating plan comes in. An operating plan might not sound glamorous, but it’s one of the most controllable and powerful tools at your disposal to turn vision into momentum without burning through cash or exhausting your team.

Conceptually, an operating plan is simple. It covers everything the company is doing: What tasks are underway? Who owns them? What goals are we pursuing? What’s the total cost? How do we measure results? Yet answers to these questions can get complex quickly, making it essential to map them out in a single plan.

Even if you’ve never created a formal operating plan for a business, you’ve likely done something similar in your personal life. For example, if you want to run a marathon, you’d create a training plan to guide your preparation over the months leading up to race day. How long should each run be? When and by how much should you increase distance? Which routes will you take? How will you rest and recover? What if you get injured? In business, your “race day” might be a product launch, an IPO, or another major milestone. The principle is the same.

But don’t confuse an operating plan with a strategic plan. A strategic plan outlines the big-picture vision—the story you tell investors. An operating plan, on the other hand, is about execution: turning that vision into actionable details involving people, costs, and timelines. Both are essential for building a healthy, thriving company.

Now, let’s dive into what an operating plan should include.

Creating an Operating Plan

Start by focusing on four core elements of operations: people (who is responsible?), time (when will each task be completed?), cost (what’s the budget?), and metrics (how will progress be measured?).

An operating plan is iterative, so don’t obsess over perfection in the first draft. There are best practices, frameworks, and even expensive consultants available. But the core work—clearly defining who is doing what in your company—is something you can and should do yourself. You can refine it later. For now, just ensure your operational goals over a given period are clear and well-structured.

Crucially, your plan must involve trade-offs. No company can do everything, so prioritization is necessary. These trade-offs should be difficult ones that force leadership to have honest conversations about what to focus on—and what to deprioritize. Trade-offs remain constant regardless of success; constraints often lead to better decisions.

Three Common Mistakes

Here are three common pitfalls to avoid when creating your operating plan.

1. Don’t be overly optimistic about timing and expected outcomes. Information changes constantly, so your plan needs to be flexible and adaptive. Watch out for dependencies: for example, “We need to launch Product A before we can launch Product B,” “We must hire two engineers before we can build that new feature,” or “Hiring one marketer will increase revenue by X.”

It’s tempting to bake such assumptions into your operating plan, but missed milestones can quickly unravel these dependencies. If hiring those two engineers takes longer than expected, your timeline for launching the new feature is at risk. So while your plan can be ambitious, it must also be realistic. Build in buffers so you can adjust course when needed—and remember to update downstream timelines accordingly.

2. Don’t try to do too many things at once. Founders often have many ideas for their business, but time and resources are limited. Pursuing everything simultaneously increases burn rate and distracts the team.

Instead, sequence activities strategically. Think about how different opportunities and capabilities can set up others for success. Maybe launching a certain product brings in new users, giving you leverage to build further. Or investing in a specific technology opens up new revenue streams. Consider how to prioritize company activities wisely and allocate time and resources accordingly.

Of course, reality is messier than any plan. As a founder, you’re uniquely aware of the range of opportunities tied to your product. It’s easy to want to chase multiple paths—partly because you see large markets behind each, and partly because core product progress may be slower than expected, prompting a desire to create multiple paths to success. But the hard truth is that small teams typically excel at only one thing. Spreading focus may seem appealing, but it often leads to under-execution on the most important priorities.

To assess focus, ask two questions: What is the company’s top priority right now? Where are employees spending most of their time? If the answers don’t align, there’s likely a problem.

3. Define measurable success criteria. Even the best operating plan is useless if you can’t track performance. Why? Because without knowing how to measure success, you can’t recognize failure—or respond effectively to challenges. Metrics don’t need to be complex; even simple red/yellow/green status indicators can work. But you must have metrics.

Remember: what you incentivize drives behavior. Carefully consider whether your chosen metrics truly drive optimal outcomes. For example, you probably want to tie incentives to output, not just hours worked.

Budgeting Essentials

The budget is a critical part of any operating plan. Your plan must answer: “How much will all this cost?” Every founder should understand basic budgeting principles.

Most companies spend most of their money on people. This isn’t always true, but it’s a useful rule of thumb—especially since founders sometimes underestimate the full cost of new hires. Beyond salary, benefits, and payroll taxes, factor in hardware, software, licenses, travel, and every other expense tied to employees. Many costs scale directly with headcount, so model your budget accordingly.

Relatedly, don’t forget to plan equity like you plan cash. Equity management deserves its own discussion, but when building hiring plans, budget for the equity you intend to grant. The same applies if your project distributes tokens to employees. Ultimately, having a clear, comprehensive compensation philosophy is crucial. Early mistakes compound over time.

Distinguish fixed from variable costs to understand budget flexibility. Know which parts of your budget can be adjusted and which cannot. Suppose you had to cut costs by 30% next week—would you know where to start? Or suppose the company is growing and you want to invest more—do you know which areas warrant increased spending? For startups, this can be challenging due to fewer variables. But the clearer your understanding of these levers, the better your decision-making will be.

Pro tip: Negotiate with vendors and service providers whenever possible, and avoid multi-year contracts to maintain flexibility.

Scenario planning is your friend. Any budget you create will be wrong—to some degree. Even mature companies face unpredictable factors. So instead of fixating on one ideal future, use scenario planning to prepare for multiple possibilities, assigning probabilities and confidence intervals. What could catch you off guard? What shifts might disrupt your current model? For example, under regulatory uncertainty, how would different outcomes affect your business? Treat your budget as a tool for learning and discussion, not just forecasting.

Maintain at least six months of cash runway. Founders often get blindsided by cash burn. Imagine your company has two years of funding but no operating plan. By year-end, you realize you hired five extra people and fell six months behind on product. Suddenly, your runway is down to six months. Without actively monitoring burn, your energy goes toward fundraising or cutting costs. Even if you secure new funding, closing the round may take longer than expected—and incur legal fees. Worse, the closer you get to zero, the weaker your negotiating position becomes.

The key to avoiding cash crunches is disciplined budgeting. As a founder, don’t delegate this responsibility entirely. While you can outsource tracking to others, you should still review monthly: compare planned vs. actual burn. Are there significant discrepancies? If so, what needs adjustment? Were cost assumptions flawed? Or was it a one-time issue?

A helpful tool for founders is zero-based budgeting. Many companies build next year’s budget by adjusting the current one up or down by 10%. While simpler, this approach discourages deep thinking about real needs. Zero-based budgeting requires starting from zero and justifying every expense. The benefit? You must defend each line item rather than blindly carry forward last year’s numbers. This ensures your budget aligns precisely with current priorities.

For founders—especially in crypto—establishing an investment policy is vital. While your risk tolerance depends on runway, always remember: capital preservation comes first.

What Operating Mode Is Your Company In?

There’s no single correct framework for an operating plan. Choose whatever helps you answer the core questions: Who is doing what, when, at what cost, and how is it measured?

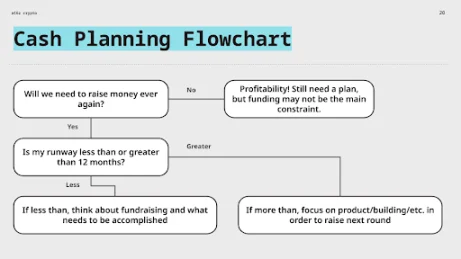

Before selecting a framework, determine your current operating mode—because it shapes your priorities. Ask yourself:

1. Does your company need to raise more funds?

The answer is likely “yes,” since most early-stage venture-backed companies raise multiple rounds—but not always. If your company is already profitable, great. You still need an operating plan, but cash may not be the primary constraint. If not yet profitable, continue to the next question.

2. Do you have more than 12 months of cash runway?

The idea is: if you have over 12 months of runway, fundraising may not be a priority this year. Perhaps your focus is product development or team building. But if runway is under 12 months, your operating plan should include fundraising, cost reduction, strategic partnerships, investment opportunities—or all of the above. You may also need to scrutinize expenses for improvement.

3. If you need to fundraise, what milestones must you achieve?

You must define what you need to accomplish to convince investors to participate in the next round. The right milestones depend on your company and the type of round you’re aiming for, so discuss this with your investors. For example, you might think launching a product will secure funding, but investors may want to see product-market fit first.

Next, consider what resources are required to reach those milestones. Identify necessary hires, other steps, and estimated timelines. Add up these costs in a spreadsheet. Does your current cash balance cover them? If not, identify variables you can adjust to achieve balance. Can resequencing help? What if you shift current priorities?

Once resources are defined, estimate how long your runway will last after hiring or investing in them. Then ask: given your current cash position, is that runway sufficient? If yes, you have a solid foundation for your operating plan. If not, revisit hiring, investments, or focus areas and iterate.

Finally, establish metrics to monitor your operating plan and assess effectiveness. Crucially, set a regular cadence—ensure reviews happen consistently.

Operating Goals Template

The worksheet below can help outline initial operating goals. One approach: define annual goals first, then work backward to quarterly, departmental, or individual tasks. The key is writing it down—trying to hold the entire plan in your head will inevitably lead to oversights.

Below is a simple example of a goal-tracking system using red/yellow/green indicators. During weekly leadership meetings, you can quickly highlight goals progressing well versus those needing attention. In this example, you might say the product is on track, marketing has minor issues but nothing urgent, and engineering faces serious problems requiring immediate discussion. The system isn’t sophisticated—that’s the point: find a method that enables both monitoring and accountability.

Creating an operating plan is essential—but don’t overcomplicate it. Focus on substance over form. Ensure you can answer basic questions: Who is doing what, when, at what cost, and how is it measured? Once you can, you’ll have a reliable benchmark to track progress and stay aligned with your plan.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News