Level Two Revelation (1): Yuezhuang Treasure Box

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Level Two Revelation (1): Yuezhuang Treasure Box

The market is like a romantic affair.

Author: Dave

Dave's "Unveiling the Secondary Market" trilogy is officially here! As the first chapter of this series, "The Insight Box" will systematically explain so-called "Zhuangxue" (the art of market manipulation)—a concept that has been both heavily criticized and excessively praised, yet never clearly defined.

Preface: Before diving into the main content—and as an opening to the entire series—I’d like to briefly explain why I’m writing this three-part series. I’ll boldly attempt a structural breakdown of how money is made in the crypto space.

-

First, in crypto, we make money in three ways: 1) earning from assets, 2) earning from operations, and 3) earning from traffic.

-

Second, regarding asset-based earnings, I further divide it into three categories: 0-level market (starting projects), 1-level market (investing in projects), and 2-level market (trading projects). These represent different stages of maturity.

On Twitter, @thecryptoskanda's “Three Platters Theory” stands as the pinnacle of 0-level market analysis, while @0x_KevinZ's beginner tutorials have mastered the 1-level market. However, the secondary market—the space most accessible to retail investors and the broadest in scope—lacks systematic coverage. This absence not only leads to conceptual confusion (such as today’s topic, the idea of “Zhuangjia,” or market manipulators), but also allows misleading trading influencers to thrive, while skilled traders remain obscure. As they say, when there are no heroes, fools rise to fame. Take @0xBanez, my most respected secondary market analyst—he never flaunts profits, but I recommend reading his posts on your knees.

So I want to share some insights on the secondary market. I won’t claim these are all profound truths, but they do represent my accumulated knowledge. I hope they help, and I also hope more experienced players will step forward to offer guidance.

In *A Chinese Odyssey*, Joker uses the Moonlight Box to reclaim lost love. In this series, let’s use the Insight Box to catch the next big market move.

"At that moment, the sword was only 0.01 centimeters from my throat. But a quarter of an incense stick later, the sword’s owner would fall deeply in love with me—because I decided to tell a lie. Though I’ve told countless lies in my life, this one felt perfect." Enough talk. Let’s begin.

1. The Debate Over Zhuangjia (Market Manipulators)

So what exactly is a "Zhuangjia"? Or rather, do they even exist? Is "Zhuangxue" a江湖 scam or a secret martial arts manual? Let’s hold off on answering for now. Instead, let’s examine a few screenshots and truly feel the misunderstood concept of the "Zhuangjia".

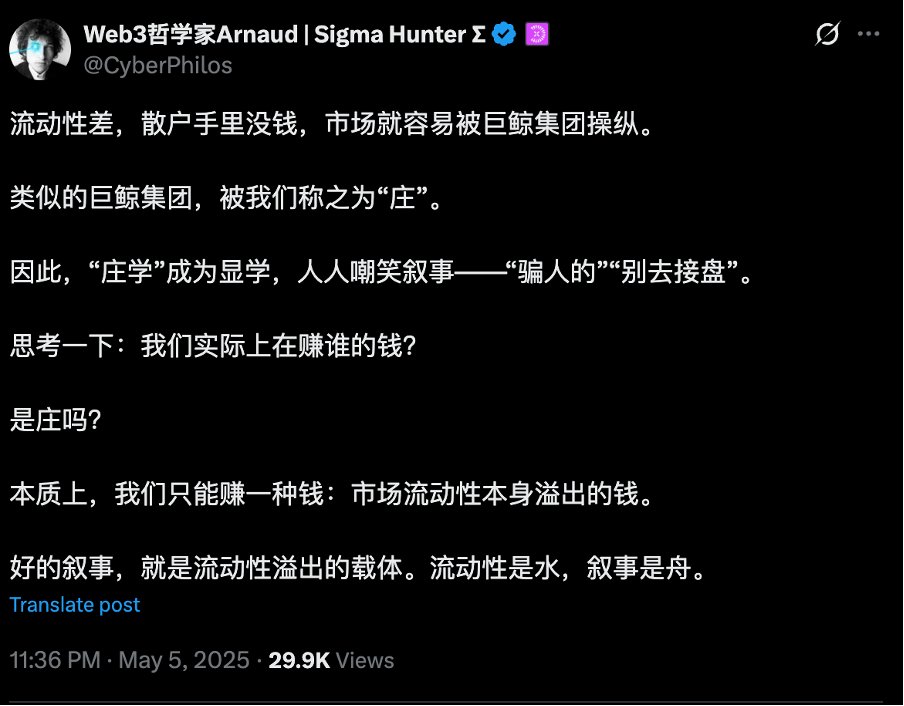

Definition of Zhuang by @CyberPhilos

Teacher Chen, controversial among the public, but @czreth's video keeps people young

My long-lost twin sister @ClaraChengGo. Three examples suffice. If you gathered all Zhuang researchers—say, someone like @liangxihuigui—and asked them to debate, they’d probably end up fighting. So is the concept of Zhuang trash or treasure? Why such divergent views?

The answer: Zhuangjia isn’t a single, fixed definition. We can view it through different lenses. In most cases, discussions about Zhuang are vague—so vague that it distorts our objective understanding. Let’s unpack this:

2. The Insight Box: Perspectives on "Zhuangjia"

The term "Zhuangjia" in casual speech actually carries two meanings. The first is a concept commonly used in Chinese-speaking communities, which I call the "designated person." The second is a globally recognized concept from Wyckoff’s "Composite Man."

2.1 Designated Person: This interpretation assigns the role of "Zhuangjia" to a specific individual, team, or group of people. This aligns with the common notion of a manipulative cartel—a belief that certain individuals or groups possess the power to control the market.

Is this valid? Not universally. For example, is there a specific team manipulating Ethereum’s price? I doubt it. But in some cases, it holds true. Let’s explore a few examples.

For instance, we say Li Daddy @Christianeth is the Zhuang behind Cheems, Qi Ge @liping007 controls Pepe, and @0xJust_ is the Zhuang for @0xUClub. These statements are accurate—they assign Zhuang status to specific individuals.

Sometimes, the Zhuang is attributed to a specific organization—e.g., @binancezh being the Zhuang for TST, or Wintermute acting as the Zhuang for certain tokens. Here, the manipulator is a concrete entity.

Finally, Zhuang can refer to a collective—e.g., Sichuan mining farm owners being the Zhuang for inscriptions, or Wall Street old money controlling Solana. These interpretations are also valid.

Possibly the most famous manipulator in human history: Rockefeller

Thus, the designated-person model applies to certain assets—there really are groups capable of manipulating them. But clearly, not every asset has such a force behind it. So why do we hear about "Zhuangjia" everywhere? Enter the second perspective:

2.2 Composite Man: I once asked my friend @MrRyanChi how to translate "Zhuangjia" into English. After thinking hard, this Hong Kong native said there’s no exact equivalent—usually translated as “banker” or “dealer,” but neither captures the full nuance.

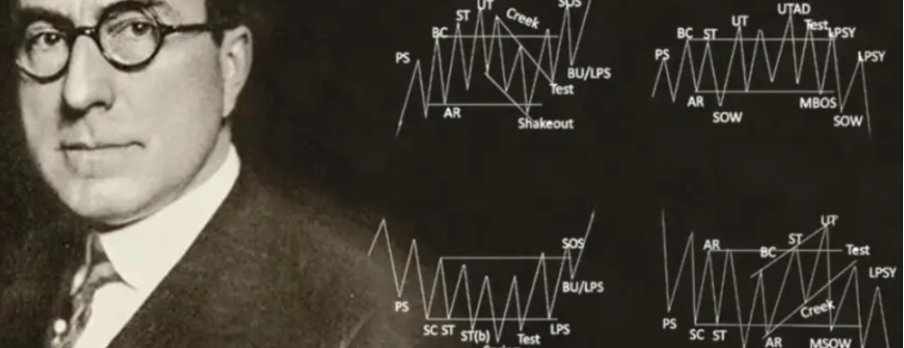

Enter Wyckoff’s volume-price analysis—the only serious technical approach rooted in the perspective of market manipulation. Wyckoff coined the term "Composite Man" (also known as “smart money”) to describe the collective behavior of large institutional investors. The Composite Man manipulates prices and retail sentiment to profit, and traders must learn to “follow the Composite Man’s footsteps.”

In global financial contexts, “Zhuangjia” isn’t a conspiracy theory—it’s a way of viewing the market. When we adopt a holistic perspective, we see that market forces behave similarly to a single manipulator. We call this abstract, collective entity the “Zhuangjia.” It’s akin to physics’ force analysis: instead of examining individual forces on multiple objects, we consider the net force on the system as a whole. In secondary markets, this systemic thinking is called “reading the Zhuang.” Coincidentally, the entities powerful enough to influence markets—large institutions or wealthy families—often resemble our conventional image of Zhuangjia.

Wyckoff—will reappear later

Understanding these two perspectives helps clarify many phenomena. For some assets, the “designated person” model dominates; for others, only the “composite” view makes sense. And during certain periods for certain assets, there may be no Zhuang presence at all—just pure random walk.

By now, we’ve largely demystified the concept of “Zhuang.” Moving forward, if you analyze a project through the lens of Zhuang, you’ll have a clearer framework. Next, we’ll explore operational models derived from these two Zhuang perspectives.

3. Eagle-Eyed Analysis: Three Models

There are countless ways a market can evolve—even Brownian motion is possible. But for practical purposes, we can categorize observable patterns into three main types:

3.1 Designated-Person Perspective: Contract Manipulation

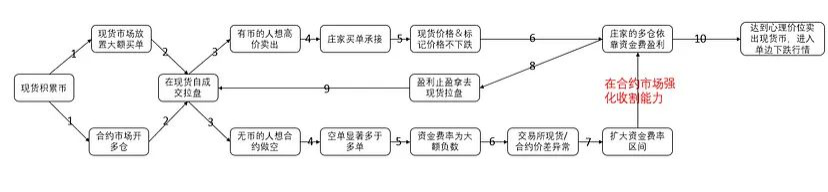

This is the most common meaning of “Zhuangjia” in secondary markets—organized groups manipulating small- and mid-cap altcoins using spot and futures to extract retail liquidity.

-

First, understand the mechanism: It all hinges on liquidity. Price moves based on supply and demand. If demand surges while supply remains tight, prices rise. A “Zhuangjia” is someone who controls significant supply. By accumulating large amounts of tokens, they reduce available supply, enabling them to easily push prices up.

-

Next, the profit mechanism: This revolves around derivatives. Understand that spot and futures markets are separate. Futures are theoretically pegged to spot prices, but they’re fundamentally different instruments. A classic example: during the 2008 crisis, credit derivatives (CDS) temporarily decoupled from underlying assets—imagine BTC falling while BTC futures rise. Arbitrage usually corrects this, but not instantly. The Zhuang’s core strategy: once they control enough spot supply, retail traders are confined to the futures market. Since futures track spot prices, the Zhuang can manipulate spot prices to liquidate opposing futures positions, seizing retail liquidity.

-

Finally, here’s a rough flowchart—and a story. Contract manipulation is a deep craft; mastering it alone could sustain a livelihood. This topic deserves its own article—if this post gains traction, I’ll write one.

Credit to @OwenJin12 & @Michael_Liu93

Financial markets abound with derivative manipulation examples. Even the “max pain” theory for options reflects how derivatives can impact spot markets. The famous CMB Oil Treasure incident saw international speculators crash crude oil prices into negative territory, destroying value in a derivative product tied to it. And then there’s our familiar Alpaca coin:

And recently, Cookie—the image is borrowed directly from Manager Mai’s tweet, purely for educational purposes:

And my personal experience—the only time I got liquidated and lost heavily: WLD.

Background: WLD’s valuation had surpassed OpenAI’s, rising wildly with massive sell pressure looming. Fundamentally, it was a prime candidate to short with everything you’ve got. But fueled by emotion, retail piled into short positions at the top—forgetting that spot prices were still controlled by the Zhuang. Shorts opened on the left side simply had their liquidity taken. So:

Two weeks of sideways movement forced direction choices—then a final-day surge of over 60%, blowing me out. I shorted around $9; had I survived the spike, I’d have profited handsomely. But youth is blind. Beware the vicious Zhuang.

That’s enough on contract manipulation. Key takeaway: Zhuang behavior in futures markets can be analyzed through the designated-person lens—a traceable but dangerous pattern.

3.2 Composite-Person Perspective: Hype Cycles & Primary-Secondary Market Linkage

For trending coins, we can’t attribute movements to individuals—we must view them as market-wide forces. Compared to violent spot-futures manipulation, these trends are milder and longer-lasting, but demand sharper logic and better information sourcing.

Examples: BTC (decadal scale), NVDA,茅台 (Maotai). We’ll dive deeper shortly.

-

Hype-driven coins rise with volatility and pullbacks, often in mature assets. The engine is multi-tiered participation—constant handoffs between different player classes. Different traders have different entry criteria, take-profit levels, etc. Thus, various主力 (main forces) drive each leg of the rally.

-

I dare suggest this underpins Elliott Wave and Fibonacci psychology: at different price points, different participants enter. Buying and selling is just passing the bag—from me to you to him. Each cohort has similar exit expectations. Maybe humans are wired to favor golden ratios—hence smooth drops until 0.5 or 0.618, where one group sees entry and another sees exit.

Those two paragraphs contain the core ideas. Now, examples.

🥃1. Maotai

Maotai’s breakout began around 2015–2016. Prior to that, sales growth was already strong, fundamentals improved, and it gradually earned the title of “National Liquor.” From 2015 onward, Maotai went through three phases.

-

2015–2018: Over 3x gain, followed by nearly a year of consolidation. The driver: business fundamentals. Sales slumped in 2012–2013, and liquor prices fell. Once resolved, Maotai’s strong business recovery materialized. It transitioned from official banquets to business and private gatherings. And yes, it tastes great—though Qinghua Lang is decent too, Maotai’s overall quality reigns supreme. With China’s economic growth, demand for premium liquor surged—boosting this leader via “consumption upgrade.” This phase was led by value investors—early entrants who studied fundamentals deeply. They included savvy speculative funds, shareholders, and risk-tolerant VCs, who helped fuel the first major run-up.

-

2018–2020: Doubled again, followed by months of shakeouts. Driver: portfolio allocation. Maotai’s image as national liquor, blue-chip, and “white horse” stock became entrenched. Major funds began seriously including it in portfolios. Two narratives emerged: Maotai as a “quasi-bond” due to stable earnings, and the rise of “X-Mao” labels (e.g., “Oil Mao” for Jinlongyu), implying Maotai = excellence. Hence, Maotai became a staple in asset allocations—its weight in白酒 ETFs and the CSI 300 became substantial. The drivers now were institutional capital flows, especially structured allocations. Like Berkshire Hathaway or Walmart, Maotai became a high-beta proxy for China’s economy. Its peak (2018–2021) naturally propelled Maotai upward.

-

2020–2021: Final glory—up 50% in 42 days, then sideways decline as macro conditions worsened. Driver: recovery frontrunner. Many believed the pandemic ended around 2020–2021. With global recovery expected, Maotai—as a flagship stock—gained favor from both retail and institutions. Plus, lifted restrictions revived banquet demand. Multiple short-term catalysts aligned. Monetary easing and Maotai’s status as a scarce core asset drew inflows. In September 2021, Maotai nearly hit its daily limit (+9.5%), reflecting狂热 sentiment. Mutual funds piled in, pushing valuations above 50x. Consensus was strong: leaders only drink Maotai (“others burn your throat”), and “Maotai = Chinese consumption” quietly took root—even fund managers thought alike.

Maotai’s handover logic:

Early value researchers >> Risk funds adding to portfolios >> Institutional allocation dominance

Later, consumption downgrade, economic slowdown, and stretched valuations led to painful sideways and downward movement. That’s Maotai’s story.

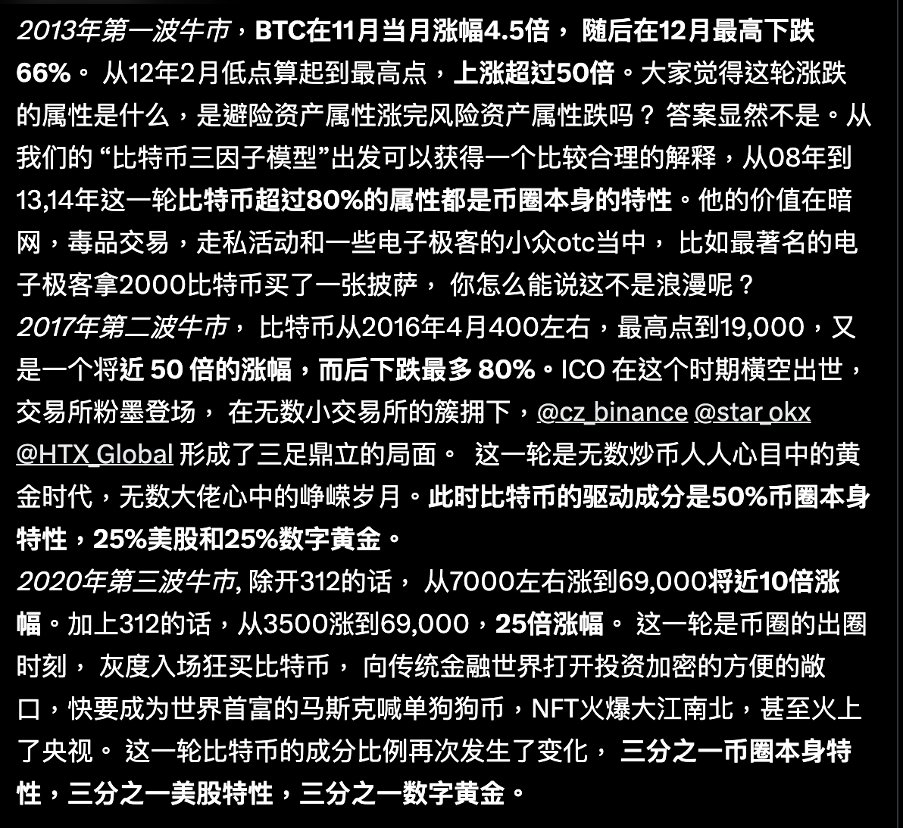

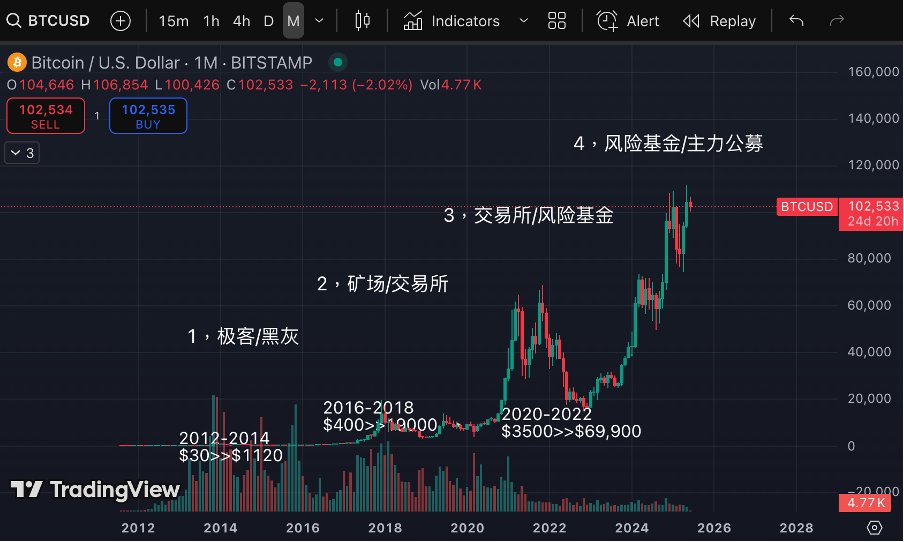

🥃2. Bitcoin

One last long-term handover example: Bitcoin. I detailed this in my article “Love, Death, and Bitcoin”—here’s a quick recap.

Bitcoin’s handover logic:

Geeks / Darknet >> Miners >> Exchanges >> US equity risk funds >> Institutional allocation

Compare this to Maotai: early discoverers → risk funds (including MSTR) → institutions. So Bitcoin at $100K? Just the beginning. It’s only now entering institutional radar. The real cooking hasn’t even started.

You might be tired—here’s a fun anecdote. Both assets seem tied to leadership preferences. Republicans favor crypto—Trump himself launched NFTs and a token. In China, leaders reportedly love Maotai—maybe Comrade Xi only drinks Maotai. Zhou Enlai definitely did. When Maotai’s market cap surpassed all military stocks combined, people were shocked. Maotai feels like Bitcoin’s stock version—both seemingly lack intrinsic value, yet soared regardless. That’s the Composite Man story.

3.3 Hybrid Perspective: Composite + Designated — Violent Pump & Zhuang Rotation

In practice, the line between Composite and Designated Zhuang is rarely clear. More often, we see hybrid models—combining elements of both. This is the most widespread pattern, with medium cycles and strong regularity.

Hybrid characteristics: explosive, consensus-driven pumps with no pullbacks. After peaking, consolidation brings delayed rationalizations. Meanwhile, the project’s fundamentals (on-chain activity) improve due to rising prices. The public accepts the new price reality and begins self-fulfilling justification—searching for virtues. With shifting macro consensus and improving fundamentals, a second wave emerges.

In short: two phases. Phase 1: aggressive pump with fuzzy logic—feels like a designated Zhuang. Phase 2: momentum driven by market consensus and fundamentals—feels like a composite force. Hence, “hybrid perspective.” Also, since these Zhuangs don’t profit from contract liquidations, they differ from Model 1.

This logic is deep—details in the next article. For now, a framework. Examples: XRP, Layer, SUI, WLD. Let’s take XRP.

Due to scaling issues, labeling the chart is tough—so I’ll explain in text. XRP is a classic American-style strong-pump token. The broader market context: November Trump victory, BTC rallying from 70K to 100K. XRP and ADA led the charge. The chart shows key phases: blue lines = uptrends, red boxes = consolidations. Notice:

-

First, extreme aggression. Second, no comfortable re-entry during pullbacks. Third, immense strength—especially visible in the second red box.

-

First surge: +110%, then flat consolidation. Second: +50%, slight dip, 20% wick, but closed within 5%. Final leg: +100%. Total pump: ~400%. Market cap breached $100B—one of 2024’s sweetest deals for large, liquidity-sensitive funds.

-

After the peak, adjustments began. Zhuang took partial profits. News spread: Ripple executives met Trump, staked funds were unlocked. The market shifted toward a composite structure. A flag pattern emerged—clean pullback—followed by another rise. Then, correlation with broader markets resumed. Looking back: the first doubling lacked logic—no insider clue explains why it led the pack. Pullbacks offered poor entries—most waited for deeper dips, but the Zhuang kept pumping. Only when fear, hype, and retail consensus peaked did the Zhuang exit at peak liquidity. The baton passed—the designated Zhuang faded, and the market evolved into a composite force. Professional traders, institutions, and leftover early players formed the new collective momentum.

These three models form the big picture. Of course, details abound—each will be explored in depth in upcoming articles. The goal of this series is to provide a cheat sheet—a guide to check against real-time market moves. After all this, you should now grasp the Zhuang concept and possess a more systematic mindset for navigating the chaotic secondary market. That’s enough.

Conclusion: Subjective trading in the secondary market—put simply, stock or crypto speculation—is essentially retail trying to read the Zhuang. And manipulators? They profit by reading the retail mindset. Profit goes to the slightly smarter party. Because human nature and trading habits don’t change, we can exploit recurring patterns—not perfect, but useful.

The Zhuang sees through retail—that’s how big scythes harvest韭菜. But after centuries of this battle, we’ve evolved our own "Insight Box." Next article will detail specific pump patterns. Feel free to suggest topics in the comments.

Lastly, market analysis is dynamic. Recently, I’ve noticed traditional chart patterns failing—perhaps the market has evolved new structures. But two things remain: First, the logic of capital markets doesn’t change. Only appearances shift; the underlying law stays. Second, there’s no holy grail. Everyone just earns money according to their own coherent worldview.

Markets are like love affairs.

Opened with Joker’s line—let’s close with Zi Xia’s:

"Do you know? I’ve been lying to you all along."

"Well then, keep lying.

Like a moth,

knowing it will get hurt,

still flies into the flame.

That’s how foolish moths are."

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News