Token vs Equity Battle: On-Chain Sovereignty vs Regulatory Constraints – How Can Crypto Economics Be Restructured?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Token vs Equity Battle: On-Chain Sovereignty vs Regulatory Constraints – How Can Crypto Economics Be Restructured?

Can tokens restrained by the SEC break free from regulatory uncertainty and redefine autonomous ownership of digital assets?

Author: Jesse Walden, Partner at Variant; Jake Chervinsky, CLO at Variant

Translation: Saoirse, Foresight News

Introduction

Over the past decade, founders in the crypto industry have generally adopted a model of value distribution that separates value between two distinct vehicles: tokens and equity. Tokens offer a novel mechanism for networks to scale in ways previously unimaginable—yet this potential hinges on tokens representing genuine utility for users. However, mounting regulatory pressure from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has significantly constrained founders’ ability to allocate value to tokens, pushing them instead toward equity. This status quo urgently needs to change.

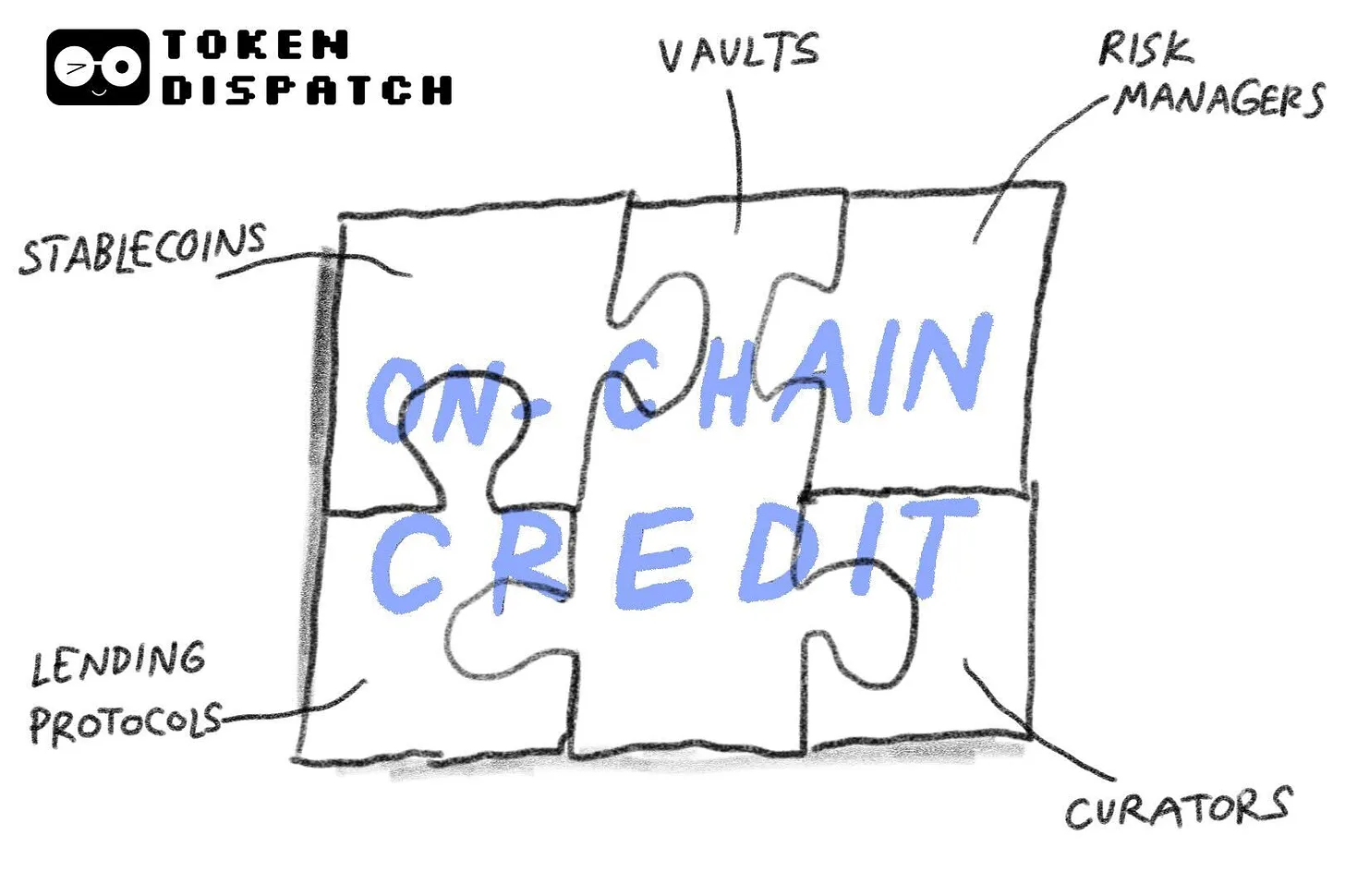

The core innovation of tokens lies in enabling “self-sovereign ownership” of digital assets. With tokens, holders can independently own and control funds, data, identity, and the on-chain protocols and products they use. To maximize this value, tokens should capture on-chain value—transparent, auditable revenue and assets directly controlled by token holders.

Off-chain value is fundamentally different. Because token holders cannot directly own or control off-chain revenue or assets, such value rightfully belongs to equity. While founders may wish to share off-chain value with token holders, doing so often carries compliance risks: the entities controlling off-chain value typically have fiduciary duties to prioritize shareholders. If founders want to direct value to token holders, that value must exist on-chain from the outset.

This foundational principle—"tokens for on-chain value, equity for off-chain value"—has been distorted since crypto’s inception due to regulatory pressure. The SEC's historically broad interpretation of securities laws has not only misaligned incentives between companies and token holders but also forced founders to rely on inefficient decentralized governance systems to manage protocol development. Now, the industry stands at an inflection point where founders can re-explore the true nature of tokens.

The SEC’s Legacy Framework Constrained Founders

During the ICO era, crypto projects frequently raised capital through public token sales while entirely bypassing equity financing. They sold tokens with promises that building out their protocols would increase post-launch token value, making token sales the sole fundraising method and tokens the exclusive vehicle of value.

But ICOs failed to pass SEC scrutiny. Starting with the DAO Report in 2017, the SEC applied the Howey Test to public token sales, concluding most tokens were securities. In 2018, Bill Hinman, then-Director of the Division of Corporation Finance, identified "sufficient decentralization" as key to compliance. By 2019, the SEC had released a complex regulatory framework that further increased the likelihood of tokens being classified as securities.

In response, companies abandoned ICOs and shifted to private equity funding. They used venture capital to fund protocol development and only distributed tokens after launch. To comply with SEC guidance, firms had to avoid any actions post-launch that might boost token value. The rules were so strict that companies were effectively required to disassociate themselves from their own protocols—even discouraged from holding tokens on their balance sheets to avoid perceived financial incentives to inflate token prices.

Founders responded by ceding protocol governance to token holders and focusing instead on building products atop the protocol. The idea was that token-based governance could serve as a shortcut to achieving "sufficient decentralization," while founders continued contributing as ecosystem participants. Additionally, founders pursued equity value creation via the strategy of “commoditizing complements”—offering open-source software for free and monetizing higher- or lower-layer products built on top.

Yet this model revealed three major problems: misaligned incentives, inefficient governance, and unresolved legal risks.

First, incentives became misaligned between companies and token holders. Forced to channel value into equity rather than tokens—to reduce regulatory risk and fulfill fiduciary duties to shareholders—founders shifted focus from market competition to business models centered on equity appreciation, sometimes abandoning commercialization altogether.

Second, the model relied on decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) to manage protocol development, yet DAOs proved ill-suited for this role. Some DAOs operated through foundations, which often faced internal incentive misalignments, legal and economic constraints, operational inefficiencies, and centralized access barriers. Others used collective decision-making, but most token holders showed little interest in governance. Token-based voting led to slow, inconsistent, and ineffective decisions.

Third, compliance designs failed to fully mitigate legal risk. Despite aiming to satisfy regulators, many companies using this model still faced SEC investigations. Token-based governance also introduced new legal liabilities—for example, DAOs could be deemed general partnerships, exposing token holders to unlimited joint liability.

In the end, the real-world costs of this model far outweighed its benefits, undermining both protocol viability and token market appeal.

Tokens for On-Chain Value, Equity for Off-Chain Value

A new regulatory environment now enables founders to redefine the proper relationship between tokens and equity: tokens should capture on-chain value, while equity captures off-chain value.

The unique value of tokens lies in self-sovereign ownership of digital assets. They grant holders ownership and control over on-chain infrastructure—systems that are globally accessible and instantly auditable. To maximize this advantage, founders should design products so that value flows on-chain, where token holders can directly own and control it.

Examples of on-chain value capture include Ethereum benefiting token holders via EIP-1559 fee burning, or DeFi protocols routing revenue to on-chain treasuries through fee-sharing mechanisms; token holders earning royalties from intellectual property licensed to third parties; or frontends in DeFi capturing fees routed entirely on-chain. The key is that value must transact on-chain, ensuring token holders can observe, own, and control it without intermediaries.

In contrast, off-chain value should belong to equity. When income or assets reside in bank accounts, commercial agreements, or service contracts outside the chain, token holders cannot directly control them. Such arrangements require the company as an intermediary, creating relationships potentially subject to securities regulation. Moreover, entities controlling off-chain value have fiduciary obligations to return profits primarily to shareholders—not token holders.

This does not invalidate equity models. Even when the core product is open-source software like a public blockchain or smart contract protocol, crypto companies can succeed using traditional business strategies. As long as the distinction—"tokens for on-chain value, equity for off-chain value"—is clear, both instruments can accrue real value.

Minimal Governance, Maximal Ownership

In this new era, founders must abandon the notion of tokenized governance as a regulatory shortcut. Instead, governance should be used sparingly and kept minimal and orderly.

One of the core advantages of public blockchains is automation. Founders should automate as much as possible, reserving governance only for what cannot be automated. Some protocols may benefit from "humans at the edges"—for instance, executing upgrades, allocating treasury funds, or overseeing dynamic parameters like fee and risk models. But governance should be strictly limited to functions exclusive to token holders. In short: the more automated, the better the governance.

When full automation isn't feasible, delegating specific governance rights to trusted teams or individuals can improve decision speed and quality. For example, token holders might authorize a development firm to adjust certain parameters without requiring universal consensus voting each time. So long as token holders retain ultimate control—including the ability to monitor, veto, or revoke delegation—the delegation model preserves decentralization while enabling efficient operations.

Founders can also use customized legal structures and on-chain tools to ensure governance functions effectively. Consider adopting new entity types like the Wyoming DUNA (Decentralized Autonomous Nonprofit Association), which grants token holders limited liability and legal personhood, allowing them to enter contracts, pay taxes, and enforce rights in court. Also consider governance frameworks like BORG (Blockchain Organizational Registration Governance) to ensure DAOs operate transparently, accountably, and securely on-chain.

Additionally, token holders’ ownership of on-chain infrastructure should be maximized. Market data shows users place minimal value on governance rights—few are willing to pay for voting power over protocol upgrades or parameter changes—but place high value on ownership rights like revenue entitlements and control over on-chain assets.

Avoiding Investment Contract Treatment

To navigate regulatory risk, tokens must be clearly distinguished from securities.

The fundamental difference lies in the rights and powers conferred. Generally, securities represent a bundle of legally enforceable rights tied to a legal entity—including economic participation, voting rights, information access, or legal recourse. Take stock: shareholders gain defined ownership interests linked to a corporation, but these rights are entirely dependent on the corporate entity. If the company goes bankrupt, those rights vanish.

Tokens, by contrast, confer control over on-chain infrastructure. These powers exist independently of any legal person—even the entity that created the infrastructure. If the founding team exits, the token-based rights persist. Unlike security holders, token holders typically lack fiduciary protections or statutory rights. Their assets are defined by code and economically independent of their creators.

In some cases, on-chain value may partially depend on a company’s off-chain operations, but this alone doesn’t necessarily trigger securities regulation. While the definition of a security is broad, the law isn’t intended to govern every situation where one party benefits from another’s efforts.

Many real-world transactions involve such dependencies without falling under SEC oversight: consumers who buy luxury watches, limited-edition sneakers, or designer handbags may expect brand-driven appreciation, yet these purchases clearly aren’t regulated as securities.

The same logic applies to many commercial contracts: landlords rely on property managers to maintain assets and attract tenants, but this relationship doesn’t make landlords “security investors.” Landlords retain full control over their assets—they can override management decisions, replace operators, or take over operations at any time. Their control exists independently of the manager’s performance.

Tokens designed to capture on-chain value resemble these physical assets more than traditional securities. When acquiring such tokens, holders understand they possess and control specific assets and powers. They may expect ongoing operations by the founding team to enhance value, but there is no legal right connecting them to the company. Their ownership and control over digital assets are independent of the corporate entity.

Ownership and control of digital assets should not constitute an investment contract. The core rationale for securities regulation isn’t “one party benefits from another’s effort,” but rather “an investor relies on a promoter in a relationship of informational and power asymmetry.” Where such reliance doesn’t exist, transactions centered on property rights shouldn’t be treated as securities offerings.

Of course, even if securities law wasn’t meant to apply, the SEC or private plaintiffs may still argue otherwise—the courts’ interpretation will ultimately decide. But recent U.S. policy developments signal positive momentum: Congress and the SEC are exploring new regulatory frameworks focused on “control over on-chain infrastructure.”

Under a “control-centric” regulatory approach, founders can legitimately create token value without triggering securities rules—as long as the protocol operates independently and token holders retain final control. While the precise path forward remains uncertain, the trend is clear: the legal system is gradually recognizing that not all value creation requires securities oversight.

Single-Asset Model: Full Tokenization, No Equity?

While some founders prefer dual-track value creation via tokens and equity, others favor a “single-asset” model, anchoring all value on-chain and assigning it solely to the token.

This model offers two primary advantages: aligning incentives between the company and token holders, and allowing founders to focus exclusively on improving protocol competitiveness. Projects like Morpho have already pioneered this minimalist design.

Consistent with traditional analysis, securities classification still centers on ownership and control—a critical consideration for single-asset models, given their concentration of value in the token. To avoid investment contract treatment, tokens must confer direct ownership and control over digital assets. While legislation may eventually formalize this structure, current challenges stem from regulatory uncertainty.

Under a single-asset architecture, the company should be structured as a non-profit entity without equity, serving only its own protocol. At launch, control must be transferred to token holders, ideally through blockchain-native legal entities like the Wyoming DUNA (Decentralized Autonomous Nonprofit Association).

Post-launch, the company may continue contributing to protocol development, but its relationship with token holders must fall clearly outside the “founder-investor” paradigm. Viable paths include having token holders delegate specific powers to the company as agent, or establishing collaboration through service contracts. Both roles are standard within decentralized governance ecosystems and should not trigger securities regulation.

Founders must carefully distinguish single-asset tokens from “company-backed tokens” like FTT, which are functionally closer to securities. Unlike native tokens that confer control and ownership of digital assets, FTT-like tokens represent claims on a company’s off-chain revenue—their value entirely dependent on the issuer. If the company fails, holders have no recourse; if the entity collapses, the token becomes worthless.

Company-backed tokens precisely create the imbalance securities law aims to correct: holders cannot audit off-chain revenue, reject corporate decisions, or replace service providers. The core issue is power asymmetry—holders are entirely dependent on the company, forming a classic investment contract that warrants regulatory oversight. Founders pursuing single-asset models must avoid such designs.

Even under a single-asset model, a company may need off-chain revenue to sustain operations—but these funds should only cover expenses, not dividends, buybacks, or other value transfers to token holders. When necessary, funding can come from treasury allocations, token inflation, or other mechanisms approved by holders, with control remaining firmly in token holders’ hands.

Founders may raise arguments such as “no public token sale means no investment,” or “no pooled assets means no common enterprise,” but none—including “lack of reliance”—guarantee avoidance of current legal risk.

Open Questions and Alternatives

The new era of crypto presents exciting opportunities for founders, but the field remains early-stage, with many questions unresolved.

One central question: Can securities regulation be avoided even when eliminating governance entirely? Theoretically, token holders could merely hold digital assets without exercising any control. But if holders are completely passive—and the company retains meaningful control—this arrangement may fall into the scope of securities law. Future legislation or regulations might recognize governance-free “single-asset” models, but for now, founders must operate within existing legal frameworks.

Another challenge concerns how founders in single-asset models handle initial fundraising and protocol development. While mature architectures are becoming clearer, the optimal path from startup to scale remains uncertain: Without equity to sell, how do founders finance infrastructure buildout? How should tokens be allocated at launch? What legal entity type should be used, and should it evolve over time? These details—and many more—remain to be explored by the industry.

Additionally, some tokens may be better classified as on-chain securities. Yet current securities regulation has largely stifled their viability in decentralized environments—environments where public blockchain infrastructure could unlock significant value. Ideally, Congress or the SEC would modernize securities laws to allow traditional instruments—stocks, bonds, notes, investment contracts—to operate on-chain and interoperate seamlessly with other digital assets. Until then, regulatory clarity for on-chain securities remains distant.

Moving Forward

For founders, there is no one-size-fits-all answer to token and equity structuring—only careful trade-offs among costs, benefits, risks, and opportunities. Many open questions can only be answered through market experimentation, as only sustained exploration will reveal which models prove sustainable.

We wrote this piece to help founders clarify their current choices and map potential solutions emerging alongside evolving crypto policy. Since the advent of smart contract platforms, ambiguous legal boundaries and stringent regulation have constrained founders’ ability to unlock the full potential of blockchain tokens. Today, the regulatory landscape is opening up new avenues for exploration.

We’ve provided a navigational map to help founders chart a course in this new territory and outlined several promising paths we believe merit pursuit. But the map is not the territory—much remains uncharted. We believe the next generation of founders will redefine the boundaries of what tokens can achieve.

Acknowledgments

We extend special thanks to Amanda Tuminelli (DeFi Education Fund), John McCarthy (Morpho Labs), Marvin Ammori (Uniswap Labs), and Miles Jennings (a16z crypto) for their insightful feedback and valuable suggestions.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News