GENIUS Stablecoin Bill Analysis

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

GENIUS Stablecoin Bill Analysis

This article will analyze the core provisions and potential impacts of the GENIUS Act.

Author: CoinW Research Institute

On May 19, 2025, the U.S. Senate passed the GENIUS Act—short for the "Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act"—by a vote of 66 in favor and 32 opposed. This marks the first time the United States has established a federal regulatory framework specifically for stablecoins. The bill has not yet taken effect and still requires passage by the House of Representatives and signature by the President. If ultimately enacted into law, it will have profound implications for the issuance and use of stablecoins. This article analyzes the core provisions and potential impacts of the legislation.

1. Core Provisions of the GENIUS Act

The Act clearly defines stablecoins as payment stablecoins—digital currencies pegged to fiat currencies like the U.S. dollar and designed for direct use in payments or settlements. Such payment stablecoins must maintain a 1:1 value parity with fiat currency at all times, backed by real, transparent reserves. These reserve assets cannot include algorithmically stabilized mechanisms or volatile crypto assets, and users must be able to redeem them for fiat currency at any time. This definition emphasizes the payment functionality of stablecoins, positioning them not as speculative or arbitrage tools.

1.1 Issuer Qualifications

Under the GENIUS Act, both domestic and foreign entities seeking to issue or circulate stablecoins in the United States must meet strict issuer qualification requirements.

For domestic issuers, only three types of institutions are eligible to issue stablecoins:

-

First, non-bank entities holding a federal license, such as licensed fintech companies. These entities are not banks but have received federal authorization. For example, Circle, the issuer of USDC, is not a bank and cannot lend or accept deposits like one, but holds a "federal license," allowing it to legally issue stablecoins in the U.S.

-

Second, regulated bank subsidiaries—banks may issue stablecoins through their subsidiaries. This provision indicates that traditional banking institutions are permitted to participate in the stablecoin market via subsidiary structures.

-

Third, state-level issuers approved by U.S. state governments whose regulatory standards have been recognized by the Treasury Department as substantially equivalent to federal standards. These compliant issuers must maintain 1:1 asset backing (e.g., cash, Treasury securities, or central bank deposits), regularly disclose reserve compositions and redemption policies, and undergo third-party audits. If a stablecoin’s circulation exceeds $10 billion, federal oversight becomes mandatory, with either the Federal Reserve or the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) serving as the regulator. This path allows smaller or early-stage projects to begin compliance at the state level before transitioning to federal oversight.

For foreign issuers, even if headquartered overseas, any entity targeting the U.S. market must comply with U.S. regulations.

First, these institutions must originate from jurisdictions with regulatory regimes comparable to the U.S., such as the UK or Singapore—countries that already have established digital asset regulatory frameworks. Entities from regions lacking stablecoin regulation may be ineligible for approval.

Second, they must register with the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).

Additionally, they must be capable of complying with lawful U.S. government orders (such as freezing or destroying tokens).

They must also hold sufficient reserves within U.S. financial institutions to ensure liquidity and redemption capacity for U.S. users.

In sum, whether domestic or foreign, the U.S. aims to bring stablecoins under a regulatory framework equivalent to traditional finance through the GENIUS Act—ensuring safety, transparency, and compliance, and preventing stablecoins from becoming a “gray zone” in the financial system. This implies that only institutions capable of meeting high regulatory standards will be allowed to issue and circulate stablecoins legally in the U.S.

1.2 Reserves and Transparency

The GENIUS Act sets clear requirements for issuers’ reserve assets. Every stablecoin issued must be fully backed by an equivalent amount of safe, liquid assets—such as cash or short-term U.S. Treasuries—with no allowance for riskier assets like equities or corporate bonds. To prevent misuse, these reserve assets must be segregated from the company’s operational funds and cannot be used for investments or collateral. Moreover, the Act explicitly prohibits paying interest or yield on stablecoins, reinforcing that stablecoins are payment instruments, not investment products, and should not compete directly with bank deposits. By disallowing interest-bearing stablecoins while permitting interest on bank deposits, the legislation may incentivize banks to enter the stablecoin space themselves, launching digital dollars or digital euros backed by both regulatory compliance and interest-bearing capabilities. While bank-issued stablecoins themselves cannot pay direct interest, banks could offer more attractive financial experiences through integrated accounts or cashback programs, enabling competition in the stablecoin arena. Thus, the future stablecoin market may evolve beyond competition among various stablecoins to a broader contest between traditional banks and crypto-native firms.

To ensure transparency, issuers must publish monthly reports detailing their reserve composition, signed off by senior executives such as the CEO or CFO, and audited by independent accounting firms. For issuers with stablecoin circulation exceeding $50 billion, annual financial audits are required to further safeguard user funds.

1.3 Anti-Money Laundering and Compliance

Under the GENIUS Act, all stablecoin issuers must comply with anti-money laundering (AML) obligations under the Bank Secrecy Act, effectively classifying them as “financial institutions” under U.S. law. They are therefore required to monitor fund flows and prevent money laundering and terrorist financing.

All payment stablecoin issuers must establish comprehensive AML and compliance systems, ensuring these digital currencies are not exploited for illegal activities such as money laundering, terrorism financing, or sanctions evasion. Key requirements include:

-

Establishing formal AML policies—issuers must document how they will prevent money laundering and communicate this to employees and regulators.

-

Appointing a designated compliance officer—a qualified individual responsible for overseeing the entire AML framework, ensuring accountability rather than mere procedural compliance.

-

User identification and verification (KYC)—all users must undergo identity verification before using the stablecoin service. Issuers must know who is using their product.

-

Sanctions screening—issuers must verify that users are not on government sanctions lists (e.g., terrorists, drug traffickers, sanctioned officials).

-

Monitoring and reporting suspicious transactions—systems must detect unusual behavior (e.g., sudden transfers of $1 million or frequent transactions to unknown addresses) and report such activity to regulators.

-

Maintaining transaction records—for audit purposes, all transactions (sender, recipient, amount, timestamp) must be securely archived.

-

Blocking prohibited transactions—issuers must have the ability to halt transactions that violate the law (e.g., payments to blacklisted websites).

Beyond policy, issuers must possess technical capabilities to promptly freeze accounts or block specific transactions upon order from the Treasury or courts. For instance, if a wallet address is linked to criminal activity, the issuer must be able to execute commands to freeze, destroy, or block those tokens.

Foreign-issued stablecoins seeking access to the U.S. market must also adhere to U.S. AML and sanctions laws. Non-compliant issuers may be blacklisted by the U.S. Treasury and barred from trading on U.S. platforms.

The core objective of this regime is to ensure stablecoins do not become conduits for illicit financial activities.

1.4 Consumer Protection

The primary goal of the GENIUS Stablecoin Act is to protect ordinary users, minimizing risks related to fund security, fraud, or issuer insolvency.

In addition to issuer qualifications and reserve requirements, the Act mandates monthly public disclosure of reserve composition so consumers can see how their funds are safeguarded. It also strictly prohibits misleading claims—such as implying that stablecoins are “government-backed” or “FDIC-insured”—to prevent users from mistakenly believing they carry the same protections as bank deposits. In reality, stablecoins are not bank deposits; they are not protected by government guarantees or FDIC insurance. If a stablecoin de-pegs, fails to redeem, or its issuer goes bankrupt, users may lose their funds with no compensation from the government.

The Act also establishes coordination between state and federal regulators to prevent regulatory arbitrage—where issuers exploit lenient state rules to avoid stricter oversight. Once a state-regulated stablecoin reaches a certain scale, it must transition to federal supervision or cease expansion.

Finally, in the event of issuer bankruptcy, the GENIUS Act prioritizes user claims above other creditors and requires expedited judicial liquidation procedures. This means users would have a better chance of recovering their funds quickly and preferentially—even if the issuing company collapses.

2. Potential Impacts

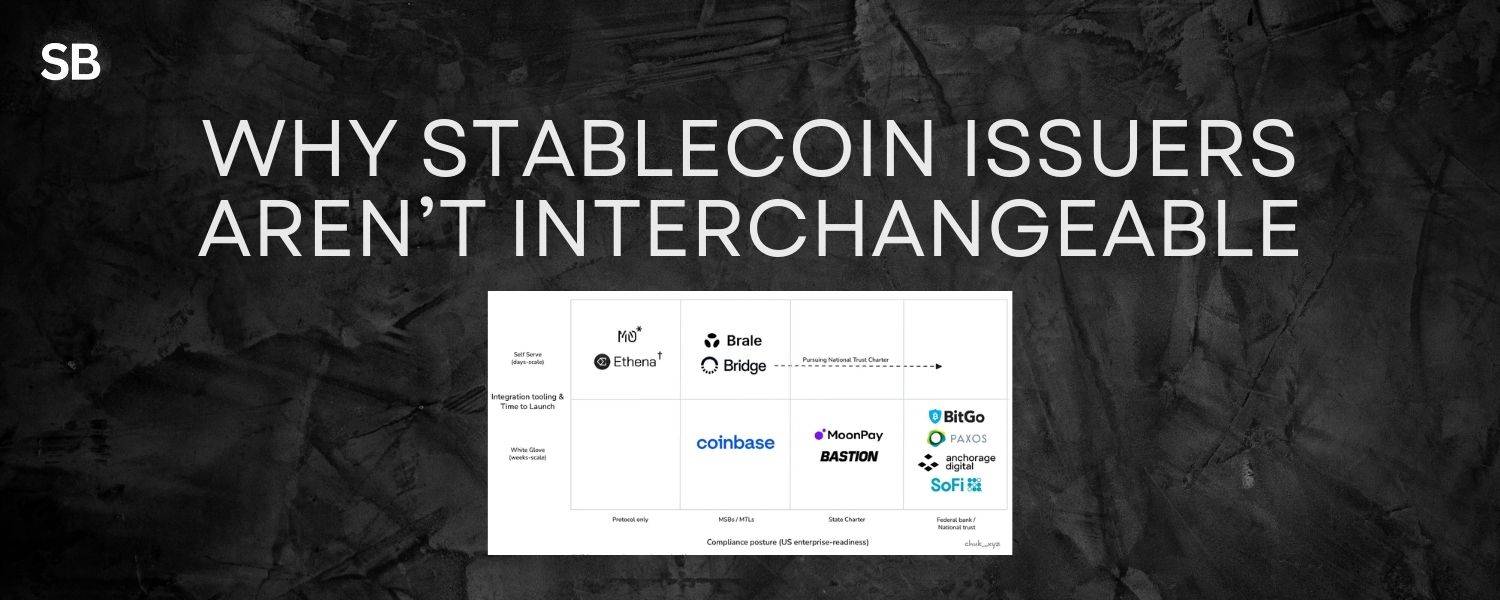

Next, we analyze how major existing stablecoins align with the GENIUS Act’s requirements.

2.1 Fiat-Collateralized Stablecoins

Fiat-collateralized stablecoins operate on a 1:1 basis—one unit issued corresponds to one dollar (or equivalent) held in secure, liquid assets like cash or short-term U.S. Treasuries. This model enables users to theoretically redeem stablecoins for real dollars at any time, resulting in high stability and low risk. These stablecoins are widely used in trading, payments, and DeFi ecosystems.

Among this category, USDC is currently the most compliant with U.S. regulatory expectations. Issued by Circle, a U.S.-based, licensed entity, USDC operates transparently and meets most requirements outlined in the GENIUS Act. As a result, USDC is poised to become one of the most policy-supported stablecoins going forward.

Another notable contender is PYUSD, launched by payment giant PayPal in partnership with regulated issuer Paxos. Both companies hold legitimate U.S. financial licenses, giving PYUSD strong compliance credentials. With PayPal’s extensive infrastructure, PYUSD is well-positioned for real-world applications in payments, remittances, and cross-border transfers—aligning perfectly with the Act’s vision of stablecoins as payment tools.

A third example is FDUSD, issued by Hong Kong-based First Digital. It maintains a relatively high compliance standard with regular audits and asset backing. However, since the issuer is not based in the U.S., its willingness and ability to comply with U.S. government directives (e.g., freezing or destroying user accounts) remains uncertain—potentially affecting its long-term viability in the U.S. market.

Currently the largest stablecoin by market cap, USDT is issued by Tether Limited, registered in the British Virgin Islands. It lacks a U.S. financial license and operates in a legal gray area. Despite its widespread adoption, increasing regulatory scrutiny under the GENIUS Act may pose significant challenges to its operations and user confidence in the U.S. market.

2.2 Decentralized Overcollateralized Stablecoins

Decentralized overcollateralized stablecoins do not rely on traditional banks or centralized institutions. Instead, users lock up crypto assets (e.g., ETH, BTC) into blockchain smart contracts and generate stablecoins through overcollateralization—ensuring price stability even during market volatility.

DAI, issued by the MakerDAO protocol, is the leading example. Users deposit assets like ETH or wBTC into smart contracts, maintaining collateral ratios typically above 150%. For instance, $150 worth of ETH can generate up to $100 in DAI, creating a buffer against price swings. DAI’s key feature is its fully on-chain, decentralized operation—no central authority can freeze accounts or seize assets, making it truly censorship-resistant. However, this design presents regulatory challenges: the GENIUS Act requires issuers to technically enable account interventions (e.g., freezing or destruction) upon government request. Since DAI cannot be unilaterally controlled or frozen, it would likely fall outside the scope of the GENIUS Act’s regulatory framework.

In summary, these stablecoins operate autonomously via code and smart contracts—appealing to users who value decentralization—but their lack of controllability makes them difficult for U.S. authorities to accept as legitimate payment instruments.

2.3 Algorithmic Stablecoins

Algorithmic stablecoins use automated algorithms to adjust supply and demand to maintain price stability, without relying on fiat reserves or crypto collateral. This mechanism typically involves minting or burning tokens: when prices fall below $1, the system burns tokens to reduce supply; when prices rise above $1, new tokens are minted to increase supply, pushing the price back toward parity.

Frax is a representative hybrid model—it is partially backed by real reserves (e.g., USDC) and partially stabilized by algorithmic adjustments. When FRAX trades below $1 (e.g., $0.98), the system triggers token burns to reduce supply and restore value.

In contrast, the collapsed UST (TerraUSD) exemplifies a pure algorithmic stablecoin. UST had no underlying collateral and was instead pegged to another token, LUNA—1 UST could always be exchanged for $1 worth of LUNA and vice versa. This worked during bullish markets but collapsed catastrophically when confidence eroded and mass redemptions triggered a death spiral: falling UST prices forced massive LUNA sales, crashing its value and destabilizing the entire system. The 2022 collapse wiped out billions in user assets, marking one of the worst disasters in crypto history.

The GENIUS Act mandates that all payment stablecoins be fully backed by highly liquid assets such as cash or short-term U.S. Treasuries, ensuring full redeemability and preventing de-pegging or bank-run scenarios. Algorithmic stablecoins, which lack real asset backing and depend solely on market dynamics and code, clearly fail to meet the Act’s 100% reserve requirement. Due to their high risk, lack of verifiable reserves, audit difficulties, and regulatory incompatibility, algorithmic stablecoins are likely to be excluded from the list of authorized issuers.

2.4 Yield-Bearing Stablecoins

Yield-bearing stablecoins automatically generate returns for holders. For example, USDe, issued by the Ethena protocol, grows in value over time like “self-appreciating dollars.” The mechanism involves deploying the underlying assets into DeFi strategies (e.g., lending, staking) and distributing the earned yield to holders.

However, the GENIUS Act explicitly prohibits any licensed stablecoin issuer from offering yield or interest to users. Stablecoins are intended solely for payment and settlement—not as investment vehicles. Therefore, yield-bearing stablecoins like USDe are unlikely to gain regulatory approval under the current U.S. framework.

2.5 Other Impacted Sectors

Beyond stablecoins, other sectors may also be affected by certain provisions of the Act.

The GENIUS Act requires issuers to identify and verify user identities—meaning all users must complete KYC before buying or using stablecoins, to prevent money laundering and terrorism financing. In this context, on-chain KYC and decentralized identity (DID) solutions become critical enablers. These tools provide stablecoin projects with compliant identity verification systems—for example, users complete KYC once in a wallet and receive an on-chain credential or passport for future transactions and audits. Projects like Fractal ID (a Web3 KYC/AML platform), Quadrata (an on-chain identity passport protocol), and Civic Pass (a system for controlling on-chain access) help issuers verify user compliance efficiently while preserving privacy. Users avoid repeatedly submitting documents, instead proving eligibility via on-chain credentials—secure and efficient.

Worldcoin, supported by OpenAI co-founder Sam Altman, uses iris scanning to issue unique digital identities (World ID), verifying users as “real humans” to combat AI-driven identity inflation. Unlike Fractal ID or Quadrata, Worldcoin emphasizes biometric authentication and global scalability, potentially becoming key infrastructure for compliant access, AML, and accredited investor verification. Furthermore, if stablecoin projects aim to serve institutional or high-value clients, on-chain KYC/DID systems can support whitelist mechanisms—only KYC-verified users can access specific services, subscriptions, or higher limits. In essence, on-chain KYC and DID function as compliance passports, helping stablecoin projects expand user bases and use cases while meeting regulatory demands. As global regulations clarify, the value of such infrastructure is likely to grow significantly.

Additionally, while the Act bans stablecoin issuers from directly paying interest, it does not prevent third-party platforms from generating yield using compliant stablecoins. For example:

Ethena is an Ethereum-based synthetic stablecoin protocol that issues USDe, pegged to $1, by constructing hedged positions combining long spot assets and short perpetual futures. Users deposit ETH or liquid staked assets (e.g., stETH), and the protocol shorts equivalent perpetuals on centralized exchanges to stabilize value. Funding rates from short positions, combined with staking yields (e.g., from stETH), generate consistent profits. Users depositing USDe receive sUSDe—a receipt token that accumulates these gains over time, effectively creating a “yield-bearing version” of USDe. Notably, yield is not paid directly to USDe holders but distributed to sUSDe holders, allowing the protocol to circumvent the GENIUS Act’s prohibition on direct interest payments.

Ondo Finance’s USDY, backed by U.S. Treasury bills and cash equivalents, offers indirect yield. Users purchase USDY with stablecoins like USDC, and the funds are invested off-chain in U.S. Treasuries. The interest generated is settled off-chain and reflected in gradual appreciation of the USDY token. Rather than receiving explicit interest, users benefit from rising token value—an approach compliant with the Act’s ban on direct interest payments. Ondo emphasizes that USDY is not a traditional stablecoin but an asset-appreciating token closer to a security or investment product.

Decentralized lending protocols like Aave and Compound allow users to deposit stablecoins (e.g., USDC, USDT), which are then lent out to borrowers who pay interest. Depositors earn a share of this interest, with the protocol retaining a spread. Since the yield originates from lending activity—not direct payments by the stablecoin issuer—this structure complies with the GENIUS Act. Compliant stablecoins can thus serve as base assets in lending markets, with issuers ensuring price stability and protocols facilitating yield generation.

Yield aggregators and arbitrage strategy platforms also enable indirect returns. Protocols like Yearn Finance automatically deploy users’ stablecoins across multiple DeFi platforms—engaging in lending, liquidity mining, or fee capture—and return net profits after fees. Users deposit stablecoins into Yearn Vaults, and their vault shares increase in value over time as returns accumulate. Withdrawals yield principal plus strategy-generated gains. Since users hold appreciating vault shares rather than interest-paying stablecoins, this model avoids violating the Act’s interest prohibition.

As long as they avoid crossing regulatory lines, third-party DeFi protocols can leverage compliant stablecoins (e.g., USDC, PYUSD, FDUSD, EUROC) as base assets to generate yield through lending, arbitrage, or hedging, effectively enabling “interest-like” returns. The GENIUS Act only bans direct interest payments by issuers, not the creation of yield-generating products by other platforms. Thus, innovation around yield using compliant stablecoins remains rich with possibilities.

3. Conclusion

The introduction of the GENIUS Act will profoundly reshape the stablecoin landscape. By establishing clear compliance standards, it favors stablecoins like USDC and PYUSD—issued by licensed entities with transparent reserves—which are likely to gain greater trust from users and institutions and see wider adoption in real-world payments and cross-border remittances. In contrast, stablecoins with unclear regulatory paths or difficulty meeting compliance requirements—such as USDT and DAI—may face restrictions, reduced liquidity, or marginalization in the U.S. market.

Moreover, the Act may accelerate market consolidation and raise industry barriers, eliminating weaker or non-compliant players and phasing out risky or substandard stablecoins. Crucially, the GENIUS Act reinforces that stablecoins should serve payment and value transfer functions—not act as investment products or speculative instruments—guiding the sector back to its foundational role as a payment tool. While short-term market adjustments and volatility are expected, in the long run, the legislation paves the way for a safer, more standardized, and sustainable evolution of the stablecoin industry.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News