Elon Musk's latest speech: Mars could become Earth's savior, Tesla robots heading there next year, human civilization structure to be rewritten

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Elon Musk's latest speech: Mars could become Earth's savior, Tesla robots heading there next year, human civilization structure to be rewritten

In the next Mars launch window, SpaceX plans to send humans to Mars.

Staying away from politics and focusing on technology—this has become Elon Musk's recent motto.

With X/xAI and Tesla entering a critical phase of technological launches, Musk recently announced on social media that he is dedicating all his energy to these tech ventures, even sleeping on factory floors—a return to the all-in, relentless "007 mode" that fans remember well.

However, this dedication hasn't brought him good news.

Despite being on-site to oversee operations, he’s still struggling to break Starship’s “three consecutive failures” curse. Yet, just now, SpaceX released a keynote speech hosted by Musk: Making Life Multiplanetary.

It might seem like the worst possible moment—right after another explosion—but Musk’s dream of Mars continues. As he put it:

You want to wake up every morning and feel that the future will be better—this is exactly what becoming a spacefaring civilization means. It means having confidence in the future, believing tomorrow will be better than yesterday. And I can’t think of anything more exciting than going to space and placing ourselves among the stars.

Key points summarized below:

SpaceX is expanding its production capacity with a goal of manufacturing 1,000 Starships per year.

Even if Earth supply lines are severed, SpaceX plans for Mars to sustain itself independently, achieving “civilization resilience,” and potentially even rescuing Earth if problems arise there.

The next key technical milestone for SpaceX is “catching” the Starship vehicle itself. The company plans to demonstrate this technology later this year, with testing expected within two to three months. The Starship will be placed atop the booster, refueled, and relaunched.

The third-generation versions of Starship, Raptor 3, and the booster will feature rapid reusability, reliable operation, and orbital propellant transfer—critical capabilities expected to be realized with Starship 3.0, scheduled for first launch by year-end.

The upcoming rocket version will already be sufficient to support humanity’s multiplanetary survival goals. Future improvements will focus on increasing efficiency, enhancing capabilities, reducing cost per ton, and lowering the expense of reaching Mars.

The Mars launch window opens every 26 months, with the next one occurring at the end of next year (approximately 18 months from now).

During future Mars windows, SpaceX aims to send humans to Mars—contingent on prior uncrewed missions successfully landing. If all goes well, the next launch could carry humans to Mars and begin infrastructure construction.

To ensure mission success, SpaceX may conduct an Optimus robot landing mission as a test during the third launch, paving the way for crewed flights.

Original video link:

https://x.com/SpaceX/status/1928185351933239641

Making Life Multiplanetary

Alright, let’s begin today’s presentation. The door to Mars has opened, and we’re now at the newly established Starbase in Texas.

This may be the first entirely new city built in the United States in decades—at least that’s what I’ve heard. The name is cool too. We call it that because here we’re developing the technology needed to take humans, civilization, and life as we know it to another planet for the first time in Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history.

Let’s watch a short video. At first, there was essentially nothing here—just a sandbar. Nothing? Even those small structures we built came much later.

That was the original “Mad Max” rocket. And it was then we realized how important lighting really was for this “Mad Max” rocket.

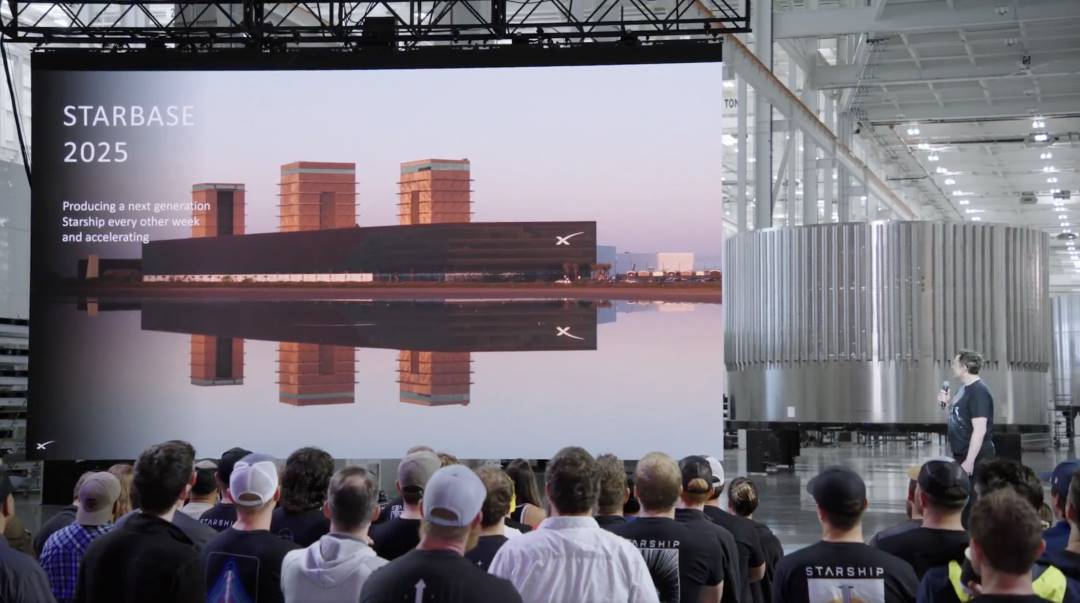

Yes, just a few years ago this place was mostly barren. But in just five or six years, thanks to the extraordinary efforts of the SpaceX team, we’ve built a small city, a massive launch platform, and a giant factory for building enormous rockets.

Better yet, anyone watching this video can actually come visit. Our entire production facility and launch site sit alongside a public road. Anyone visiting southern Texas can get extremely close to see the rockets and tour the factory.

So if you’re interested in the largest flying object on Earth, you’re welcome anytime—just drive down that road. It’s truly incredible. And here we are now—Starbase, 2025.

We’ve now reached a pace of roughly one ship every two to three weeks. Of course, we don’t rigidly produce one every few weeks because we’re still iterating on design. But our ultimate goal is to build 1,000 ships per year—that’s three per day.

This shows current progress. I’m standing inside that building right now. That’s our hovercraft transporting a booster to the launch site—you can see the mega bays.

As I said earlier, the coolest thing for viewers is that you can actually come here yourself. Driving along this road lets you witness everything firsthand—an opportunity never before available in history. The road on the left is open to the public. You should absolutely come visit—I highly recommend it. I think it’s deeply inspiring.

We’re expanding integration capacity to reach the 1,000-Starships-per-year target. It’s not complete yet, but we’re building it. This is a true megaproject—by some measures, it could become one of the largest buildings on Earth. It’s designed specifically to produce 1,000 Starships annually. We’re also building a second facility in Florida, giving us dual production bases in Texas and Florida.

The sheer scale is hard to grasp visually. You need a person standing beside it for contrast to truly appreciate how massive it is.

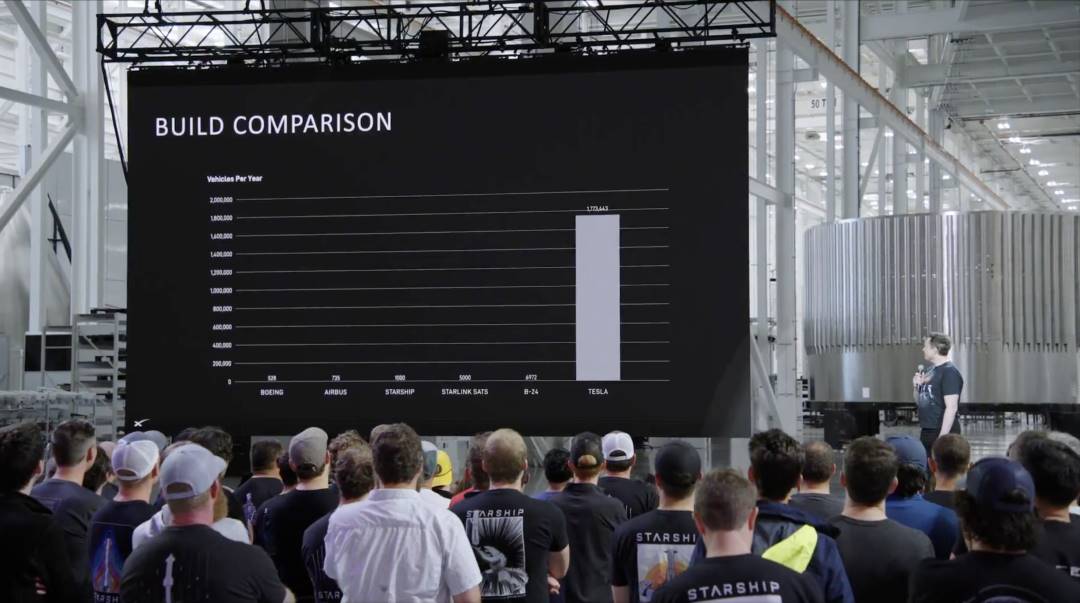

If we compare annual vehicle output—like Boeing and Airbus aircraft—Starship’s future annual production could eventually match their commercial jet output. This project is truly enormous.

And each Starship far exceeds the payload capacity of a Boeing 747 or Airbus A380—it’s a true “megaship.”

Now, regarding Starlink satellites: third-generation satellite production is around 5,000 units per year, possibly approaching 10,000 in the future. Each third-gen satellite is roughly the size of a Boeing 737—very large. Comparing it to WWII-era B-24 bombers isn’t an exaggeration.

Of course, this scale is still smaller than Tesla. Tesla’s future annual output could be double or even triple this amount.

These comparisons help establish a mental framework: producing vast numbers of interplanetary Starships is feasible. Even in total mass terms, carmakers like Tesla and others already produce more complex products at higher volumes than SpaceX.

In other words, these seemingly outrageous numbers are well within human capability—other industries have already achieved similar scales.

We measure our progress by one standard: the time required to achieve a self-sustaining civilization on Mars. Every Starship launch, especially in early stages, is part of continuous learning and exploration—laying the foundation for making humanity multiplanetary, refining Starship until it can transport tens of thousands, even millions, of people to Mars.

Ideally, anyone who wants to go to Mars should be able to do so, and we’ll also deliver all the equipment needed for Mars to become self-sufficient, enabling an independent society to develop there.

Even in the worst-case scenario, we must reach a critical turning point: Mars must be able to continue developing even if Earth stops supplying it. That’s when we achieve “civilization resilience”—and Mars might even rescue Earth if serious problems occur here.

Of course, Earth might assist Mars too. But most importantly, the coexistence of two independently functional, strong planets is crucial for the long-term survival of human civilization.

I believe any multiplanetary civilization could last ten times longer—or far beyond that. Single-planet civilizations always face unpredictable threats—like self-destructive conflicts (e.g., World War III, though we hope it never happens) or natural disasters such as asteroid impacts or super-volcano eruptions.

If we have only one planet, a single catastrophe could end civilization. But with two, we can survive—and expand further, to the asteroid belt, Jupiter’s moons, and beyond, eventually reaching other star systems.

We can truly go among the stars, making science fiction a reality.

To achieve this, we must build “rapidly reusable” rockets to minimize flight cost and cost per ton to Mars. This demands rockets capable of fast reuse.

Internally, we often joke about “rapid, reusable, reliable” rockets—the three Rs, like a pirate’s “RRRR.” These three Rs are key.

The SpaceX team has made astonishing progress in catching giant rockets.

Think about it—we’ve repeatedly “caught” the largest flying object ever built by humans mid-air using a novel method: giant “chopsticks” grabbing it from above. This is an incredible technological breakthrough.

Let me ask—have you ever seen anything like this before?

Again, congratulations to everyone. This is an extraordinary achievement. We use this unprecedented method because it’s essential for achieving rapid rocket reuse.

The Super Heavy Booster is massive—about 30 feet (9 meters) in diameter. If it lands on a platform with landing legs,

we’d have to lift it again, retract the legs, and reload it onto the launch mount—a complex process. But if we can use the same tower that initially placed it on the launch mount to catch it mid-air and immediately reset it, that becomes the optimal path to rapid reuse.

In other words, the same mechanical arms that placed the booster on the launch mount also catch it and immediately return it to position.

Theoretically, the Super Heavy Booster could relaunch within an hour of landing.

The flight itself takes only 5 to 6 minutes. Then the tower arms catch it and return it to the launch mount. Refueling takes about 30 to 40 minutes, and reloading the ship on top—so in principle, we could launch once per hour, or at minimum once every two hours.

This is the ultimate state of rocket reusability.

The next major step is “catching” the Starship vehicle itself. We haven’t done this yet, but we will.

We aim to demonstrate this technology later this year, possibly testing it in as little as two or three months. Afterward, Starship will be placed back on the booster, refueled, and relaunched.

Starship’s turnaround time will be slightly longer than the booster’s because it needs to orbit Earth several times until its trajectory returns over the launch site. Still, Starship is planned to achieve multiple daily flights.

This is the new Raptor 3 engine—excellent performance. Kudos to the Raptor team—this is incredibly exciting.

Raptor 3 is designed without a traditional heat shield, significantly reducing weight at the engine base while improving reliability. For example, minor fuel leaks simply discharge into the already hot plasma environment, posing no real problem. But if the engine were enclosed in a structural box, such leaks would be dangerous.

This is Raptor 3. We may need several rounds of testing, but this engine represents a massive leap in payload capacity, efficiency, and reliability. It’s truly revolutionary.

I’d even say Raptor 3 looks almost like “alien technology.”

When we first showed experts images of Raptor 3, they said the engine wasn’t fully assembled. We told them: this is the “unassembled” version—it’s already running at unprecedented efficiency levels.

And it runs extremely cleanly and stably.

We simplified the design extensively—integrating secondary fluid loops, wiring, and other components directly into the engine structure. All critical systems are well-encapsulated and protected. Frankly, this is engineering excellence.

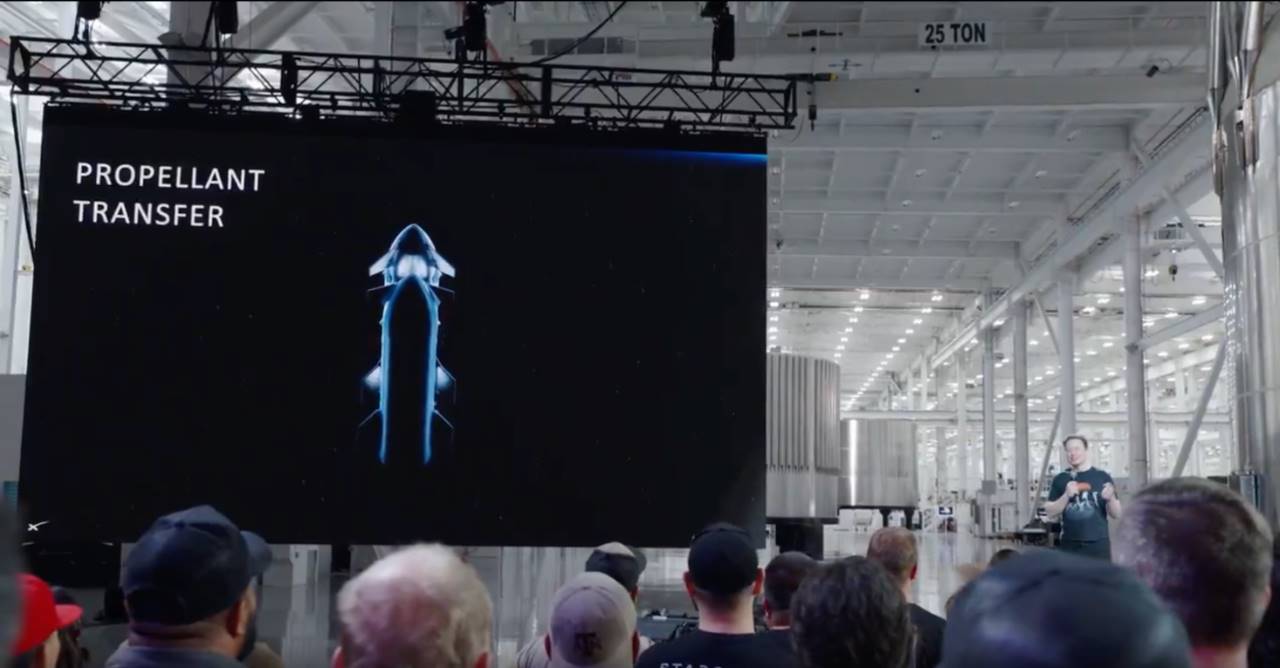

Another technology critical to Mars missions is orbital propellant transfer. Think of it as “in-flight refueling,” but in orbit—for rockets. Never done before in history, but technically feasible.

Though the process might look a bit “NSFW,” propellant transfer must happen—there’s no way around it.

Two Starships dock in orbit; one transfers propellant (fuel and oxygen) to the other. Most of the mass is oxygen—nearly 80%, with fuel around 20%.

Our strategy: launch one cargo-loaded Starship into orbit, then launch several “tanker” Starships to refill it via orbital refueling. Once full, that Starship can depart for Mars, the Moon, or elsewhere.

This technology is crucial—we hope to complete its first demonstration next year.

One of the hardest challenges ahead is the “reusable heat shield.”

No one has truly developed an orbital heat shield that can be reused many times. It’s an extremely difficult technical challenge. Even the Space Shuttle’s heat shield required months of repairs after each flight—fixing damaged tiles, inspecting each one individually.

Re-entry heat and pressure are incredibly harsh. Very few materials can withstand such extremes—mainly advanced ceramics like glass, alumina, or certain carbon-based materials.

But most materials corrode, crack, or flake after repeated use—they can’t endure the stress of re-entry.

This will be humanity’s first truly reusable orbital-grade thermal protection system. It must be extremely reliable. We expect years of refinement and optimization ahead.

Still, this technology is achievable. We’re not chasing impossibility—it’s physically feasible—just extremely difficult.

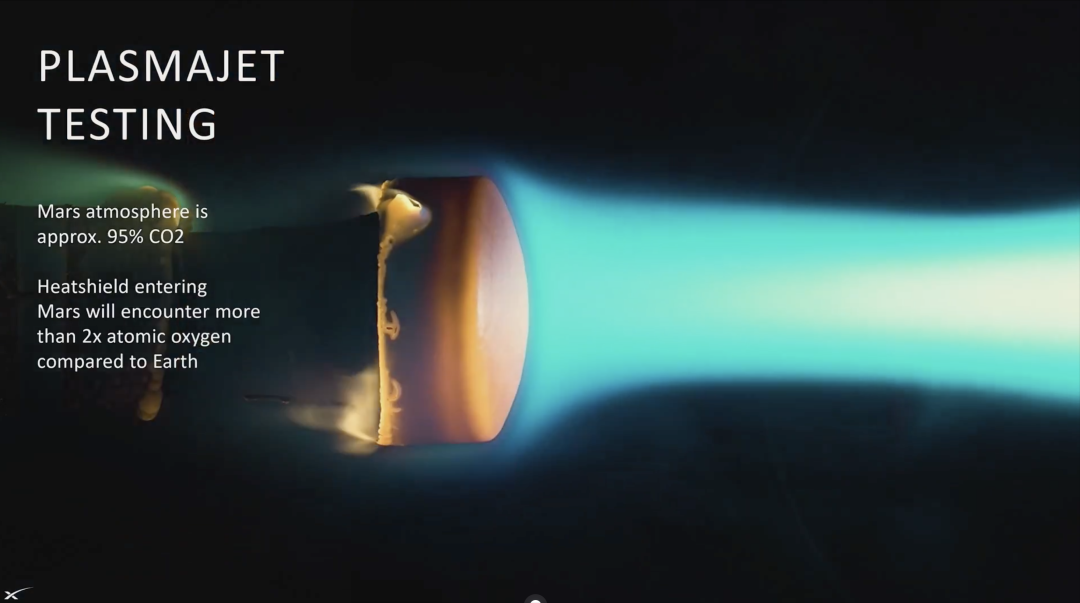

Mars’ atmosphere, though mostly CO₂ and seemingly “milder” than Earth’s, is actually worse.

When CO₂ turns into plasma during re-entry, it breaks down into carbon and oxygen—meaning free oxygen in Mars’ atmosphere exceeds Earth’s. Earth’s atmosphere has ~20% oxygen, but post-plasma decomposition on Mars could result in oxygen levels two or three times higher.

This free oxygen aggressively oxidizes the heat shield—essentially burning it away. So we must conduct rigorous testing in CO₂ environments to ensure reliability not just on Earth, but on Mars.

We aim to use the same heat shield system and materials for both Earth and Mars. The heat shield involves many technical details—ensuring tiles don’t crack or detach. Testing the same material hundreds of times on Earth gives us confidence it will work reliably on Mars.

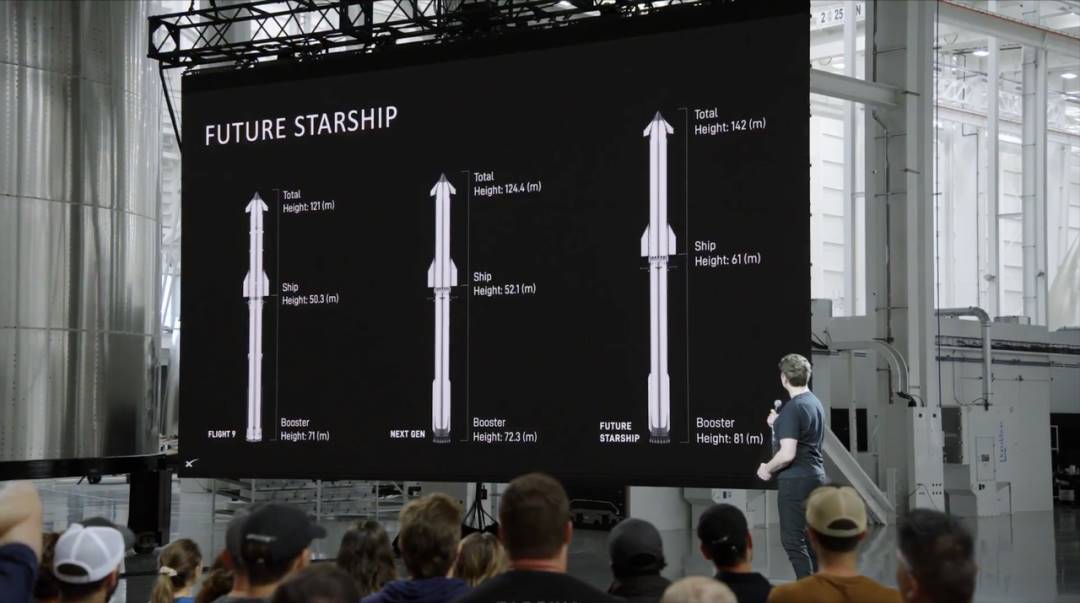

We’re also developing the next-generation Starship, featuring many improvements over the current version.

For example, the new Starship is taller, with an improved “interstage” structure between the ship and booster. You can see new struts, making “hot staging” smoother.

Hot staging means igniting the Starship engines while the booster is still firing. Flames from Starship engines can now flow through the open strut structure more smoothly, avoiding interference with the booster.

This time, we won’t discard these structures—they’ll fly with the Starship and be recovered.

The new version is slightly taller—up from 69 to 72 meters. Propellant capacity will increase slightly, likely reaching 3,700 tons long-term. I estimate it could approach 4,000 tons.

In thrust—specifically thrust-to-weight ratio—we may reach 8,000 tons, eventually pushing toward 8,003 tons—as we continuously optimize. I estimate we’ll ultimately achieve configurations with 4,000 tons of propellant and nearly 10,000 tons of thrust.

This is the next-generation, updated form of the Super Heavy booster.

The bottom may look somewhat “bare” because Raptor 3 engines don’t need heat shields—so it looks like something’s missing, but actually, these engines don’t require protective structures.

Raptor 3 is directly exposed to hot plasma but is designed to be lightweight and doesn’t need extra shielding.

This system integrates hot-stage structures—I think it looks very cool. The new Starship body is also slightly longer, more capable, with propellant capacity increased to 1,550 tons. Long-term, it may increase by another ~20%.

The heat shield design is also smoother, transitioning seamlessly from the shield edge to the leeward side—no longer jagged tiles. I think it looks clean and elegant.

The current version still has 6 engines, but future versions will upgrade to 9.

Thanks to Raptor 3 improvements, we’ve achieved lower engine mass and higher specific impulse—greater efficiency. Starship Version 3 is a major leap forward. I believe it achieves all our core objectives:

Typically, a new technology matures fully after three generations. The third-generation versions of Raptor 3, Starship, and the booster will possess all the critical capabilities we need: rapid reusability, reliable operation, and orbital propellant transfer.

These are essential conditions for making humanity multiplanetary—and they will be realized with Starship 3.0. We plan its first launch by year-end.

You can see on the left the current state, in the middle our year-end target version, and on the right the long-term development direction. Final height will be around 142 meters.

But even the middle version launching by year-end will fully support Mars missions. Later versions will offer further performance enhancements. Just as we did with Falcon 9, we’ll keep lengthening the rocket and increasing payload. That’s our roadmap—simple and clear.

But I emphasize: the version launching by year-end is already sufficient to support humanity’s multiplanetary survival goal. Next steps involve improving efficiency, enhancing capabilities, reducing cost per ton, and lowering individual trip costs to Mars.

As I said earlier—our goal is to enable anyone who wants to move to Mars or help build a new civilization to do so.

Imagine how cool that would be. Even if you don’t want to go, maybe your son, daughter, or friend does. I believe this will be one of humanity’s greatest adventures—going to another planet and building a new civilization with our own hands.

Yes, ultimately our Starship will have 42 engines—it’s almost fated, like the great prophet Douglas Adams wrote in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: the Ultimate Answer to Life is 42.

So Starship will also have 42 engines—that’s how the universe intended it (laughs).

Now, regarding payload capacity—the most astonishing fact is that in fully reusable mode, Starship will have a 200-ton low-Earth-orbit capacity. What does that mean? It’s twice the payload of the Saturn V moon rocket. And Saturn V was expendable, while Starship is fully reusable.

If used expendably, Starship’s LEO capacity could reach 400 tons.

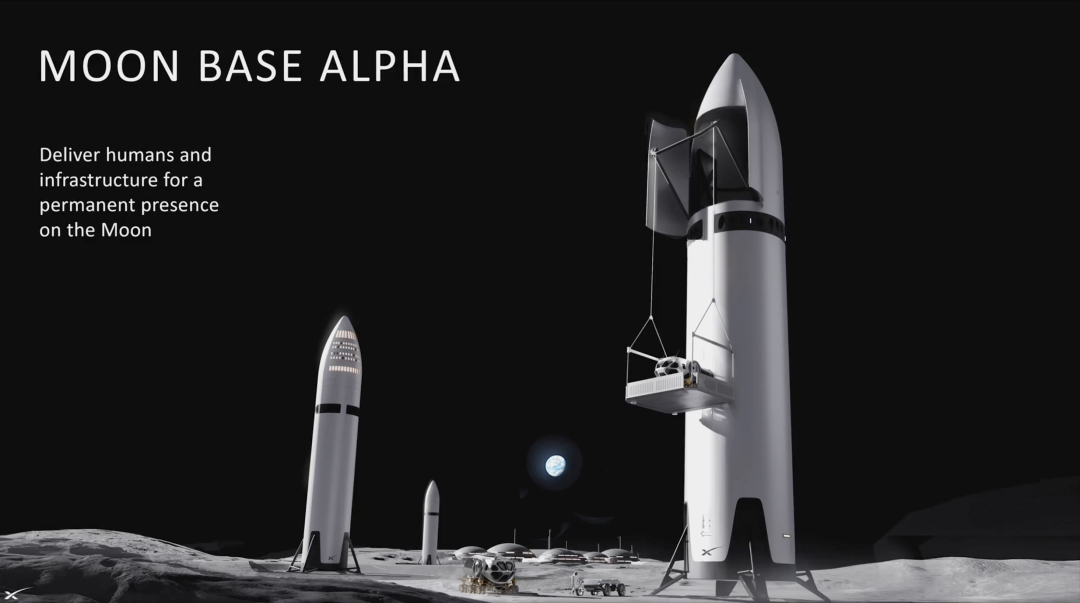

So I’m saying: this is a very large rocket. But to achieve “human multiplanetary survival,” we need such a large rocket. And along the way to Mars colonization, we can do many cool things—like building a base on the Moon—Moon Base Alpha.

Long ago there was a TV show called Moon Base Alpha—though some physics in it wasn’t realistic, like the moon base drifting out of Earth orbit (laughs)—but anyway, building a lunar base should be the next step after Apollo.

Imagine building a giant scientific station on the Moon to study the nature of the universe—that would be incredibly cool.

So when can we go to Mars?

Mars launch windows open every two years—specifically every 26 months. The next window is at the end of next year, about 18 months from now, likely November or December.

We’ll strive to seize this opportunity. If we’re lucky, I think we currently have about a 50-50 chance of success.

The key to Mars missions is timely completion of orbital propellant transfer technology. If we complete it before the window opens, we’ll launch the first uncrewed Starship to Mars by year-end next year.

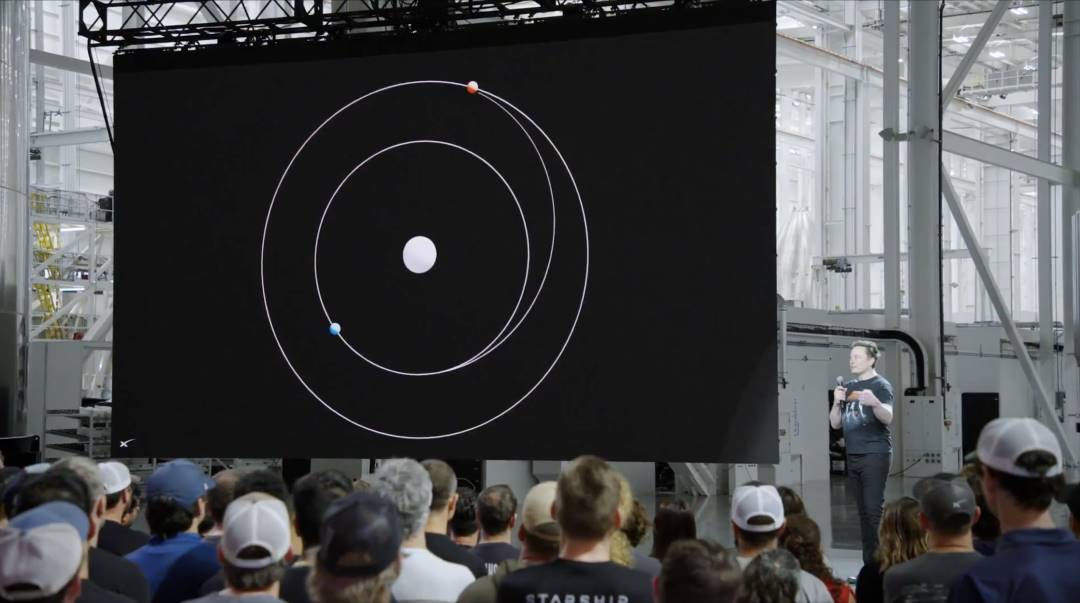

Next, you’ll see a diagram showing the flight path from Earth (blue) to Mars (red).

Actually, the distance traveled from Earth to Mars is roughly a thousand times that to the Moon.

You can’t fly “straight” to Mars—you must follow an elliptical transfer orbit, with Earth at one focus and Mars at the opposite end. You must precisely calculate the spacecraft’s position and timing to intersect Mars’ orbit.

This is known as a Hohmann Transfer—the standard method for traveling from Earth to Mars.

If you have a Starlink Wi-Fi router, check its logo—it illustrates this orbital transfer. The satellite internet service provided by Starlink is one of the projects helping fund humanity’s journey to Mars.

So I want to especially thank everyone using Starlink—you’re helping secure the future of human civilization, helping make humanity a multiplanetary species, helping usher in the era of spacefaring. Thank you.

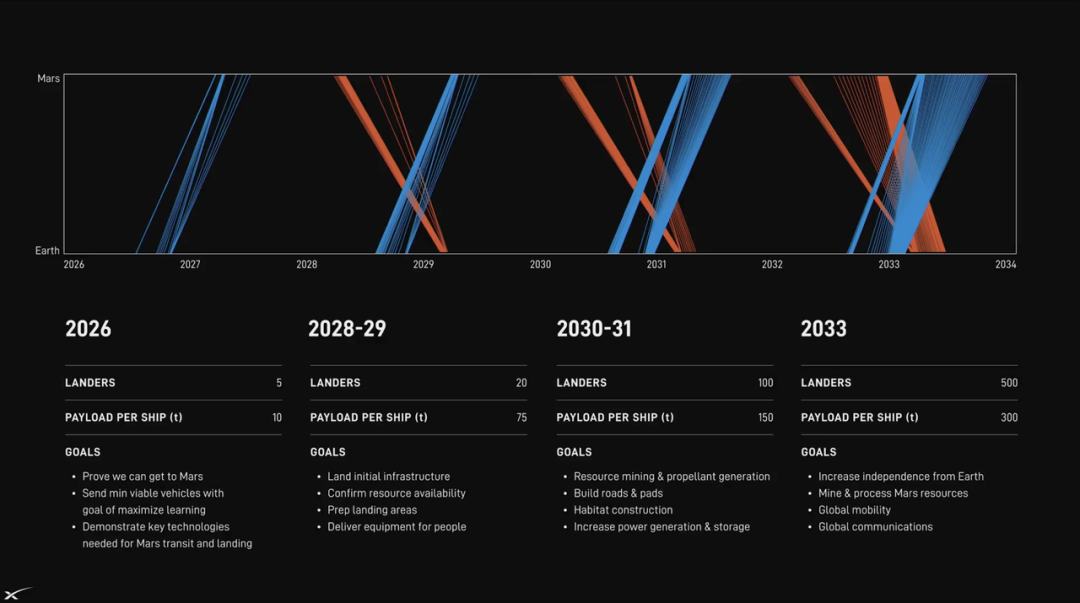

This is a preliminary blueprint: with each Mars launch window (~every two years), we aim to significantly increase flight frequency and the number of Starships sent to Mars.

Ultimately, our goal is to launch 1,000 to 2,000 Starships to Mars per window. This is a rough order-of-magnitude estimate, but based on my judgment, establishing a self-sustaining civilization on Mars will require delivering about one million tons of material to the Martian surface.

Only when Mars reaches this foundational capability can we truly say it has achieved “civilization safety”—meaning it can survive and develop independently even if Earth stops sending supplies.

You can’t miss anything—not even tiny but critical elements like vitamin C. Mars must have everything it needs to grow genuinely.

I estimate around one million tons—maybe ten million, hopefully not a hundred million, that would be too much. But in any case, we’ll do everything possible to reach this goal quickly and safeguard humanity’s future.

We’re currently evaluating multiple candidate sites for Mars bases. Arcadia is one of the leading options. While Mars has plenty of land, combining all factors narrows the choices:

Not too close to the poles (too extreme), near ice for water access, and terrain not too rugged for safe rocket landings.

Considering all factors, Arcadia is one of the more ideal locations. By the way, my daughter’s name is also Arcadia.

In the initial phase, we’ll send the first Starships to Mars to collect critical data. These ships will carry Optimus humanoid robots—they’ll arrive first, explore the surroundings, and prepare the site for human arrival.

If we truly launch a Starship by year-end next year and it successfully reaches Mars, that will be a breathtaking scene. Based on orbital cycles, that spacecraft will arrive at Mars in 2027.

Imagine the iconic moment: Optimus humanoid robots walking on the Martian surface—that will be a historic milestone.

Then, two years later during the next Mars window, we’ll attempt to send humans to Mars—provided previous uncrewed missions land successfully. If all goes well, our next launch will put humans on Mars and begin constructing infrastructure.

Naturally, to be more cautious, we might conduct another Optimus robot landing mission, using the third launch as a precursor to crewed flights. Details depend on results from the first two.

Remember that famous photo—workers eating lunch on a steel beam atop the Empire State Building? We hope to capture similarly iconic images on Mars. For communications, we’ll deploy a version of the Starlink system to provide internet service.

Even at light speed, Earth-Mars communication delay is significant—best case about 3.5 minutes, worst case when Mars is on the far side of the Sun, delays can reach 22 minutes or longer.

So high-speed communication between Earth and Mars is challenging, but Starlink has the capability to address it.

Next, the first humans on Mars will lay the groundwork, establishing permanent outposts. As I said earlier, our goal is to enable Mars to become self-sustaining as quickly as possible.

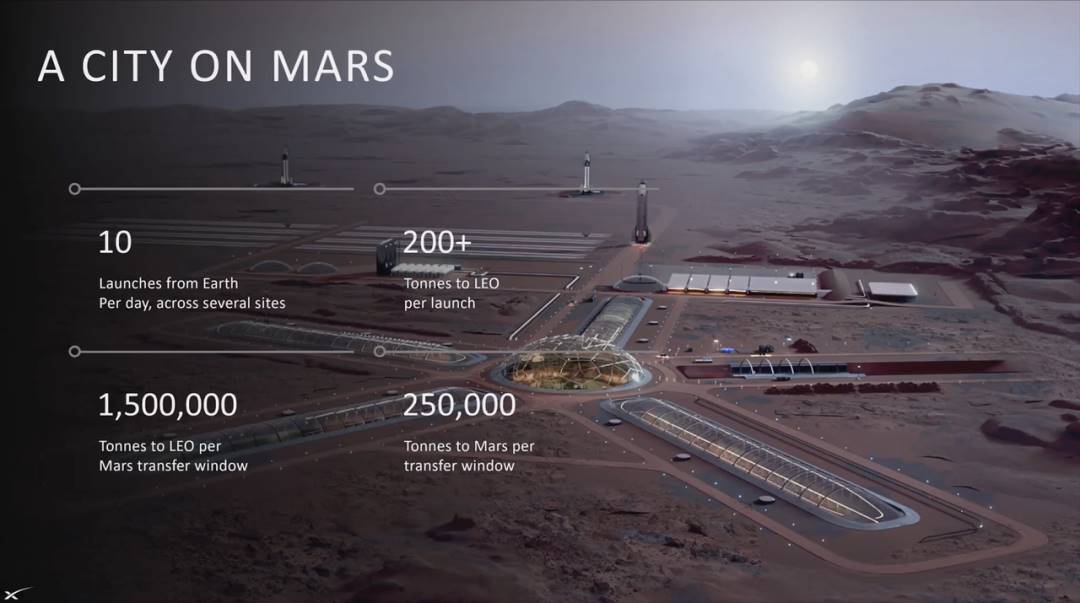

This image shows our rough concept for the first city on Mars.

I suspect we’ll place launch pads far from landing zones to prevent accidents. On Mars, we’ll rely heavily on solar power. In Mars’ early stages, before terraforming, humans won’t be able to walk freely on the surface—we’ll need “Mars suits” and live in enclosed structures, perhaps under glass domes.

But all this is achievable. Ultimately, we hope to transform Mars into an Earth-like planet.

Our long-term goal: during every Mars transfer window (~every two years), transport over one million tons of material to Mars. Only at this scale can we truly begin building a “serious Mars civilization”—million-ton shipments per window is our ultimate benchmark.

At that point, we’ll need numerous spaceports. Since flights can’t happen anytime but must cluster around launch windows, we’ll have thousands—perhaps up to two thousand—Starships gathering in Earth orbit, preparing to launch simultaneously.

Imagine—like Battlestar Galactica—thousands of ships assembling in orbit, launching together for Mars—one of the most spectacular scenes in human history.

Naturally, we’ll also need many Mars landing and launch pads. With thousands of Starships arriving, you’ll need hundreds of landing spots, or an extremely efficient system to quickly clear landing zones after touchdown.

We’ll solve that later (laughs). Anyway, building humanity’s first extraterrestrial city on Mars will be an incredible feat. It’s not just a new world—it’s also an opportunity: Mars settlers can rethink the model of human civilization.

What form of government do you want?

What new rules do you wish to establish?

On Mars, humanity has the freedom to rewrite the structure of civilization.

That decision belongs to the Martians.

So, alright—let’s go make it happen.

Thank you!

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News