From Ancient Rome to Modern Cryptocurrencies: Lessons in Risk Management

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From Ancient Rome to Modern Cryptocurrencies: Lessons in Risk Management

Big risks can make you soar, unmanaged risks can make you crash.

Author: Santisa

Translation: Block unicorn

Preface

-

Clear goals effectively control risk;

-

Big risks can make you soar; unmanaged risks will crush you;

-

As you climb, upside shrinks—scale down when risk exceeds reward;

Cryptocurrency and history are my two greatest passions. I could say 80% of my waking hours are spent on these two topics. I've noticed that many of the people we remember aren't those who "succeeded" through sound risk management. More often, they're those who kept raising their bets until collapsing spectacularly. Figures like Julius Caesar, Do Kwon, Alexander the Great, and Sam Bankman-Fried operated similarly. An insatiable appetite for risk propelled them to the top of their fields—and the same appetite led to their downfall. The long-term outperformers are the rare few who know how to switch between risk-taking and risk-avoidance depending on circumstances and goal attainment.

This article first explores two key risk-takers and managers from ancient history and their modern counterparts in the crypto industry. We'll discuss gamblers, hubris-driven figures, and those true survivors who adjusted their bets according to goals and appropriately reduced risk after achieving them.

The Original King of High-Stakes Bets: Gaius Julius Caesar

Caesar was a mid-tier Roman noble who built his career on immense personal charisma, brilliant strategy, and—most importantly—massive debt. He climbed the ranks rapidly, eventually becoming consul, but instead of waiting years at each post, he took enormous risks and debts to accelerate his rise. After becoming consul at age 41, to avoid legal and financial reckoning, he leveraged himself heavily and, through bribery, secured a five-year governorship of Gaul in 58 BC. At the time, his debts amounted to roughly 10% of Rome’s annual tax revenue—about 133,333 soldier-month salaries, equivalent to approximately $333 million today*. (* Conversion assumes a Roman legionary earned 900 sesterces annually, roughly comparable to a modern U.S. enlisted soldier's $30,000 salary.)

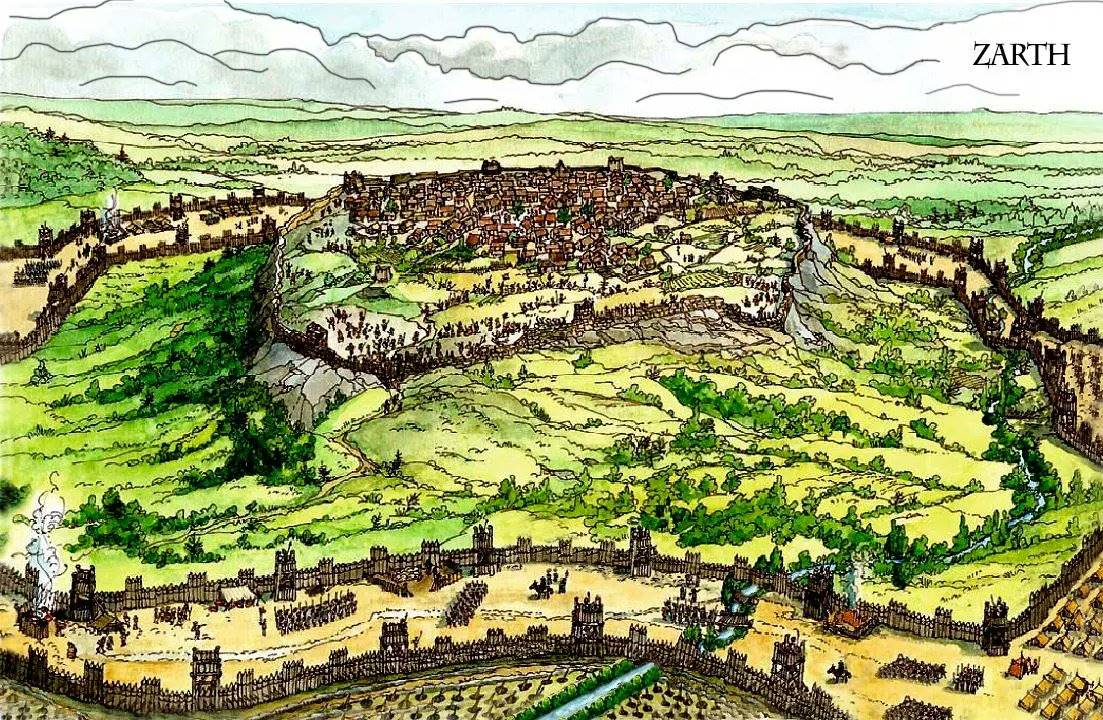

Maximally leveraged, Caesar invaded Gaul. Failure meant bankruptcy, exile, or execution. At the siege of Alesia, a relief force of 250,000 approached from behind. Any rational commander would have retreated. But Caesar, already riding high, had not only arrogant confidence—he had no choice: buried in both financial and legal debt, and with his term as governor (which granted immunity) nearing its end. So he doubled down, held his position, and built an additional outer wall. Now, about 70,000 Romans faced around 320,000 Gauls**. (** These troop numbers are estimates provided by Caesar himself in antiquity and may be exaggerated.)

Alesia was a fortified city in northern Gaul, the final stronghold where the Gauls under Vercingetorix made their last stand against Roman rule.

Caesar won. Gaul was conquered. The victory brought him immense wealth—at least on paper—but much of it was locked in illiquid assets (mostly slaves). As his governorship ended, the Senate issued an ultimatum: “Return to Rome and answer for your crimes (and debts).” Caesar always seized opportunities as he saw them; consequences could be dealt with later. Now was “later,” and he felt he had no options left. He gambled again, leading one legion across the Rubicon River, declaring “the die is cast” (alea iacta est).

The Rubicon River marked the boundary of Italy proper; crossing it meant war against the Senate.

No one expected such a bold, unprecedented move. Rome had no standing army; he captured the city, fought a civil war, and won. He now ruled the Roman world alone. But still unsatisfied, he aimed for the title “King of Rome.” Ignoring the Kelly Criterion (you should only bet a fraction of your capital proportional to your edge; exceeding this inevitably leads to long-term ruin), he went all-in once more. This final trade blew up his account: instead of receiving an email from Binance, he was stabbed 23 times by a group of senators. The same risk appetite that elevated him to power also cost him his life.

Octavian’s Rise

After Caesar’s death, his 18-year-old nephew Octavian was posthumously adopted, but Caesar’s general Mark Antony blocked the inheritance. Octavian borrowed against the promised estate, raising about $2.5 billion—roughly 750% of Caesar’s original debt—to boost his status and raise an army. This looked like Caesar 2.0, but it was a calculated move with a clear objective: Octavian pursued defined goals, not the game for its own sake.

Octavian changed his name to Gaius Julius Caesar, later Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus. Roman names are complex, so in this article we refer to him simply as "Octavian."

He knew stagnation could mean death; taking on debt and risk gave him a chance to survive and succeed. He won more civil wars—first against the Senate, then against Antony. After becoming sole ruler of the known world, he realized that further risks offered diminishing returns. He rejected the title of “king,” choosing instead “First Citizen” (princeps), publicly respecting the Senate while secretly controlling everything. Having achieved his goals, he transformed from a highly leveraged risk-taker into a conservative administrator, ruling Rome for forty years and establishing a dynasty that lasted nearly a century.

In every journey, clear goals effectively control risk. If you don’t know what “victory” looks like, how can you win? Goals shift unless you fix them in place.

Continuous gambling becomes addictive; whether out of necessity or pure thrill, we keep justifying greater risks until we become our own worst enemy.

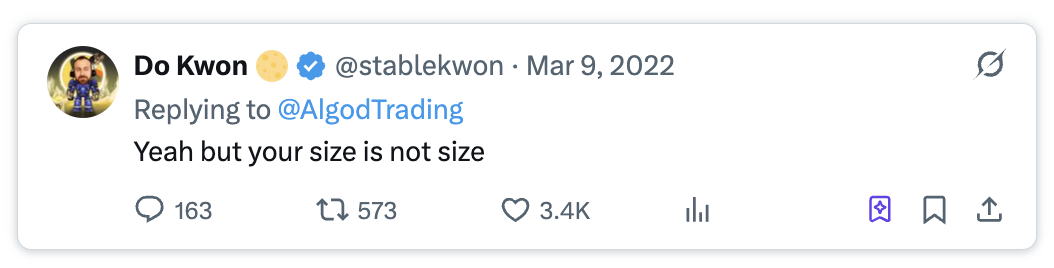

Do Kwon

Like Caesar, Do Kwon was born into a Korean elite family. He built his career on personal charisma, strategy, and—once again—massive leverage.

The Terra/Luna reflexive stablecoin system he created relied on perpetual debt. For every dollar the system absorbed, it generated even larger liabilities, meaning no amount of capital could ever close the loop. Each UST milestone was reached using borrowed capital; unlike Caesar, Do Kwon had no “Gaul” to conquer—no calculated bet, only leverage for leverage’s sake. He stuck with the risk to the end, ending up in a cold prison cell in Montenegro. What cost Caesar his life cost Do Kwon his freedom.

Do Kwon was arrested in Podgorica on March 23, 2023, attempting to flee to Dubai with a fake passport.

Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF)

SBF, founder of the bankrupt exchange FTX, used customer funds to prop up the platform, buy global influence, and finance various ventures while living extravagantly. He raised $1.8 billion, pushed FTX’s valuation to $32 billion, and maintained direct ties to Washington. Like Octavian, he took huge risks with a worldview of domination. But while Octavian learned from Caesar’s fatal overreach, SBF did not: he went all-in, repeatedly. Had he stopped in time, he could have paused the fraud, slowly patched FTX’s balance sheet gaps; instead, he doubled down and lost everything. His fate didn’t have to be so tragic.

SBF entering court in New York in 2023.

Changpeng Zhao (CZ)

CZ bet everything on speed and regulatory gray zones. He raised Binance’s funds via ICO in mainland China. Binance fully exploited regulatory arbitrage: allowing deposits and trading without KYC, listing any trading pair, and offering up to 125x leverage on obscure pairs—essentially operating a casino.

A backlash was obvious and inevitable. CZ’s gamble was that he’d grow large enough to make it worthwhile and accumulate sufficient capital (financial and political) to mitigate the fallout. The reckoning came in 2024, when he was sentenced to four months in the lowest-security prison in the U.S., and Binance was forced to pay a $4.3 billion fine. It could be said that while SBF sought leverage within customer deposits, CZ sought it by placing himself beneath enforcement actions. It’s fair to say that if Binance hadn’t grown to its current scale, the regulatory response might have resembled the decades-long sentences faced by Tornado Cash developers, and the industry’s view of this “best-of-all-time” CZ would be entirely different.

Conclusion

Caesar’s goals kept shifting upward with his success, requiring infinite leverage—which statistically meant his collapse was only a matter of time. Octavian, by contrast, risked his entire portfolio early (the best time to do so, when risk capital is smallest), then abandoned high-risk strategies as his capital grew and returns relative to his goals diminished.

Do Kwon built the entire system on leverage—not as a means to an end, but as the end itself. Like Caesar, he was ultimately liquidated. SBF’s path didn’t have to end so tragically. He made morally questionable, highly illegal, and extremely leveraged decisions—though nearly all great historical figures did the same. The crucial difference is that he failed to reduce risk as returns decayed. CZ, in contrast, mastered this skill.

Leverage is an incredibly powerful tool. Used correctly, it maximizes opportunities with positive expected value and enables life-changing moves. Yet miscalculation or excessive leverage can destroy you. My biggest takeaway is that turning leverage into a habit—becoming numb to unleveraged returns—statistically leads to ruin. Ever-rising goals will eventually leave you far below where you started. Clear goals effectively control risk.

“Every battle has an element of luck; ignore luck, and disaster follows”—Loading screen, *Rome: Total War*

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News