Why the growing popularity of stablecoins makes the Federal Reserve more anxious

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Why the growing popularity of stablecoins makes the Federal Reserve more anxious

Stablecoins reveal a core tension: the conflict between an efficient, programmable full-reserve system and a leveraged credit mechanism capable of driving economic growth.

Author: @DeFi_Cheetah, @VelocityCap_ investor

Translation: zhouzhou, BlockBeats

Editor's Note: Stablecoins combine technological innovation with the financial system, enhancing payment efficiency while challenging central banks' control over money. Functioning similarly to "full-reserve banks," they do not create credit money but may still affect liquidity and interest rates. Their future development might evolve toward fractional reserve models or integration with CBDCs, reshaping the global financial landscape.

Below is the original content (slightly edited for clarity):

The rise of blockchain finance has sparked intense debate about the future of money—topics once confined to academia and central bank policy circles. Stablecoins—a digital asset designed to maintain parity with fiat currencies—have become a mainstream bridge between traditional finance and decentralized finance (DeFi). While many are optimistic about stablecoin adoption, from a U.S. perspective, promoting stablecoins may not be ideal, as they could disrupt the dollar’s monetary creation mechanism.

In brief: Stablecoins effectively compete with deposit sizes in the U.S. banking system. As such, they weaken the money creation mechanism based on the "fractional reserve system" and reduce the effectiveness of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy (whether through open market operations or other means of controlling money supply), because they decrease total deposits within the banking system.

Crucially, compared to banks that leverage long-term bonds in the money multiplier process, stablecoins have very limited money creation capacity, as they primarily use short-term Treasury securities as collateral—assets less sensitive to interest rate changes. Therefore, widespread use of stablecoins in the U.S. could impair the effectiveness of the "monetary transmission mechanism."

Even though stablecoins may increase demand for Treasuries and lower the U.S. government’s refinancing costs, their impact on money creation remains significant.

Only when dollars used as collateral flow back into the banking system as "bank deposits" can money creation remain unchanged. But in reality, this is unprofitable for stablecoin issuers, who would otherwise forfeit risk-free Treasury yields.

Banks also cannot treat stablecoins as fiat deposits, since stablecoins are issued by private entities, introducing additional counterparty risk.

The U.S. government is also unlikely to redirect funds flowing into the stablecoin ecosystem—from Treasury purchases—back into the banking system. Because these funds are invested at different interest rates, the government would have to pay the spread between Treasury yields and bank deposit rates, increasing federal fiscal burdens.

More critically, the "self-custody" nature of stablecoins is incompatible with the custodial mechanisms of bank deposits. Aside from on-chain assets, nearly all digital assets require custody. Thus, the expansion of stablecoin scale within the U.S. directly threatens the normal functioning of the money creation mechanism.

The only way to make stablecoins compatible with money creation is to allow stablecoin issuers to operate as banks. However, this presents major challenges involving regulatory compliance, entrenched financial interests, and more.

From a global strategic standpoint, however, promoting stablecoins benefits the U.S. government: it extends the dominance of the dollar, reinforces its status as the world’s primary reserve currency, enables more efficient cross-border payments, and greatly assists non-U.S. users in regions urgently needing stable currencies. The difficulty lies in advancing stablecoins domestically without undermining the domestic money creation mechanism—a highly challenging task.

To further explain the core arguments of this article, we analyze the operational logic of stablecoins from multiple angles:

- Fractional Reserve System vs. Full Reserve Backing: How stablecoins differ fundamentally from traditional commercial banks in reserve structure.

- Regulatory Constraints and Financial Stability: How stablecoins challenge existing monetary policy frameworks, market liquidity, and systemic stability.

- Future Outlook: Potential regulatory models, hybrid fractional reserve systems, and pathways for central bank digital currency (CBDC) development.

Fractional Reserves vs. Fully Reserved Stablecoins

The Classic Money Multiplier Mechanism

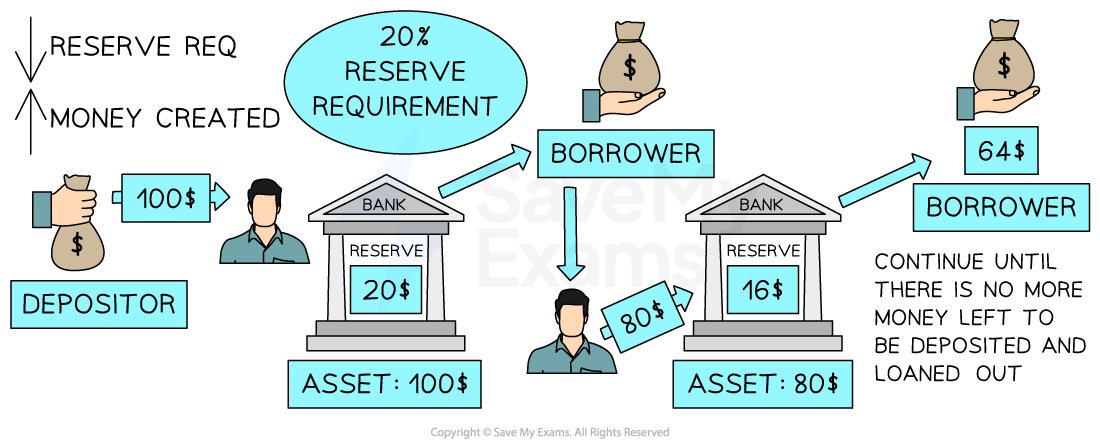

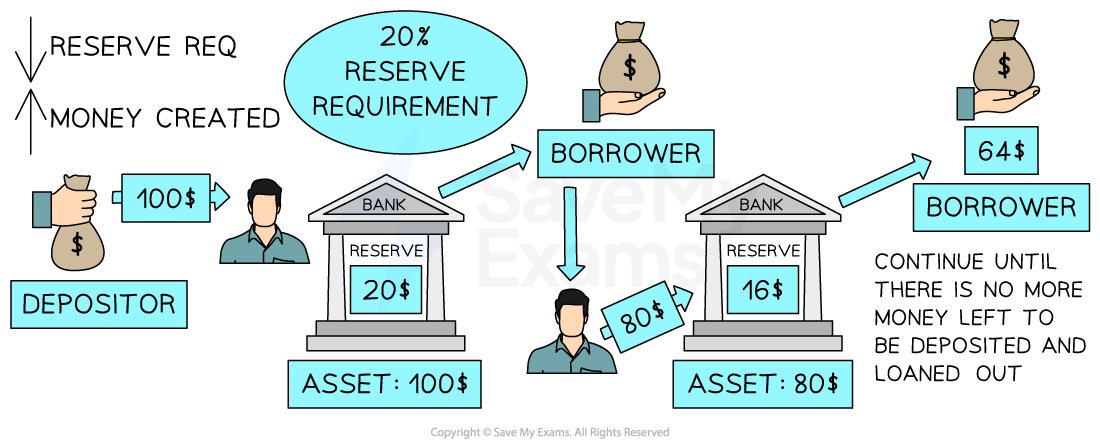

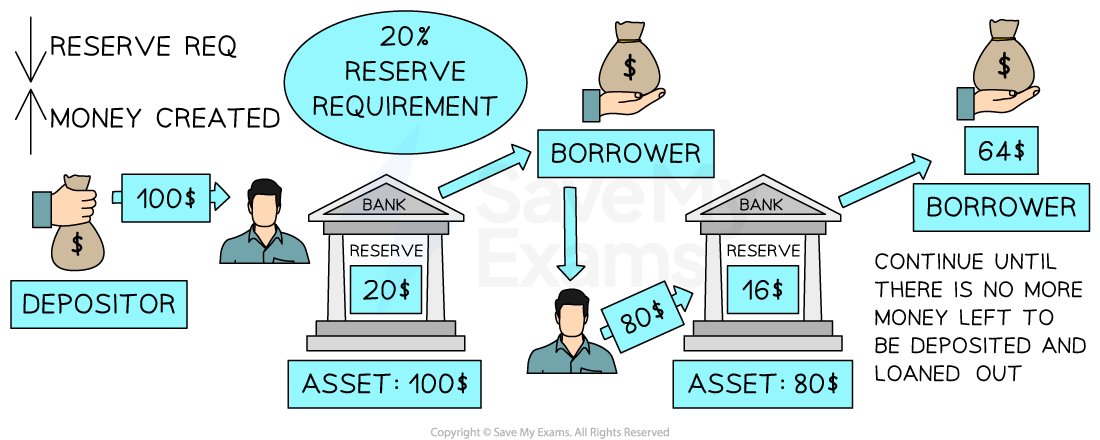

In mainstream monetary theory, the core mechanism of money creation is the "fractional reserve system." A simplified model illustrates how commercial banks expand base money (typically denoted as M0) into broader forms of money like M1 and M2.

If R is the required or bank-determined reserve ratio, the standard money multiplier is approximately: m = 1 / R

For example, if banks must hold 10% of deposits as reserves, the money multiplier m is about 10. This means that every $1 injected into the system (e.g., via open market operations) could ultimately generate up to $10 in new deposits across the banking system.

- M0 (Monetary Base): Cash in circulation + reserves held by commercial banks at the central bank

- M1: Cash in circulation + demand deposits + checkable deposits

- M2: M1 + time deposits, money market accounts, etc.

In the U.S., M1 ≈ 6 × M0. This expansion mechanism underpins modern credit systems and serves as the foundation for mortgages, corporate financing, and other productive capital activities.

Stablecoins as "Narrow Banks"

Stablecoins issued on public blockchains (such as USDC, USDT) typically promise 1:1 backing by fiat reserves, U.S. Treasuries, or other high-liquidity assets. Unlike traditional commercial banks, these issuers do not "lend out" customer deposits. Instead, they issue digital tokens fully redeemable for "real dollars" to provide liquidity on-chain.

From an economic perspective, such stablecoins resemble narrow banks—financial institutions that back their "deposit-like liabilities" entirely with high-quality liquid assets.

Theoretically, the money multiplier effect of such stablecoins is close to 1: unlike commercial banks, when a stablecoin issuer receives $100 million in deposits and holds an equivalent amount in Treasuries, no "additional money" is created. However, if these stablecoins gain broad market acceptance, they can still function as money.

We will explore further below: even without intrinsic multiplier effects, the underlying capital mobilized by stablecoins (e.g., funds from U.S. Treasury auctions purchased by stablecoin firms) may be re-spent by the government, potentially creating an overall monetary expansion effect.

Impact on Monetary Policy

Federal Reserve Master Accounts and Systemic Risk

For stablecoin issuers, access to a Federal Reserve master account is critical, as institutions with such accounts enjoy several advantages:

- Direct access to central bank money: Balances in master accounts constitute the highest tier of liquidity (part of M0).

- Access to Fedwire: Enables near-instant settlement for large-value transactions.

- Eligibility for standing facilities: Including the Discount Window and Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER).

However, granting stablecoin issuers direct access to these facilities faces two major obstacles:

- Operational risk: Integrating real-time blockchain ledgers with Fed infrastructure may introduce new technical vulnerabilities.

- Loss of monetary control: If large volumes of money shift permanently into 100%-reserved stablecoin systems, the Fed’s reliance on the fractional reserve credit mechanism for monetary policy could be undermined.

As a result, traditional central banks may resist treating stablecoin issuers equally with commercial banks, fearing loss of intervention capability over credit and liquidity during financial crises.

The "Net New Money Effect" of Stablecoins

When stablecoin issuers hold large amounts of U.S. Treasuries or other government debt, a subtle yet crucial phenomenon emerges—the "double-use effect":

- The U.S. government finances spending using public funds (i.e., proceeds from stablecoin issuers buying Treasuries);

- Meanwhile, those stablecoins continue circulating in markets as functional money.

Thus, even without the strong multiplier effect of fractional reserves, this mechanism may effectively "double" the available pool of spendable dollars in circulation.

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, stablecoins open a new channel through which government borrowing flows directly into the transactional economy, enhancing the real-world liquidity of the money supply.

Fractional Reserves, Hybrid Models, and the Future of Stablecoins

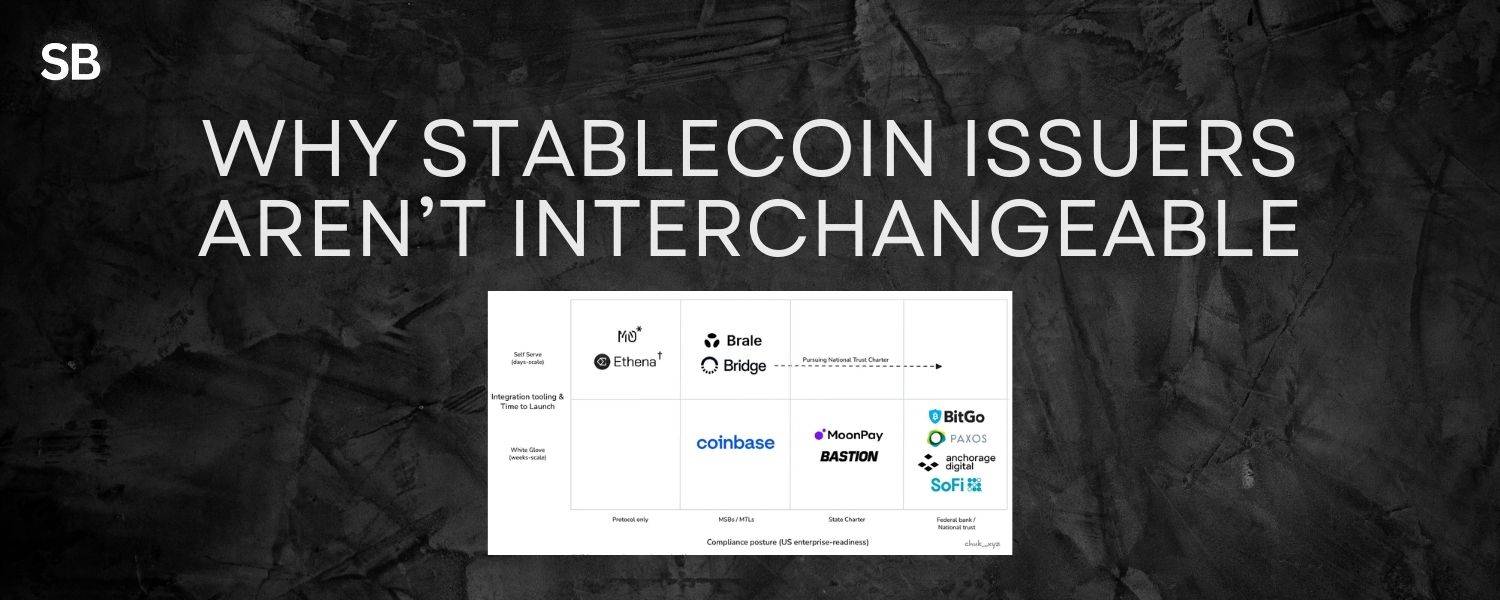

Will stablecoin issuers evolve into "bank-like" entities?

Some speculate that in the future, stablecoin issuers may be allowed to lend out part of their reserves, mimicking the fractional reserve mechanism of commercial banks to create money.

To achieve this, strict regulatory frameworks similar to those governing banks would need to be introduced, such as:

- Bank charters

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) coverage

- Capital adequacy requirements (e.g., Basel Accords)

While legislative proposals like the GENIUS Act offer pathways for "bank-like" treatment of stablecoin issuers, most still emphasize 1:1 reserve requirements, suggesting that a shift toward fractional reserves remains unlikely in the near term.

Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)

A more radical alternative is for central banks to issue their own Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs)—digital liabilities issued directly by the central bank to the public and businesses.

Advantages of CBDCs include:

- Programmability (similar to stablecoins)

- Sovereign credit backing (state-issued)

However, CBDCs pose a direct threat to commercial banks: if the public can open digital accounts directly at the central bank, massive withdrawals from private banks could occur, weakening banks’ lending capacity and potentially triggering a "digital bank run."

Potential Impact on the Global Liquidity Cycle

Today, major stablecoin issuers (e.g., Circle, Tether) hold tens of billions of dollars in short-term U.S. Treasuries, and their fund flows already exert tangible influence on U.S. money markets.

- If users redeem stablecoins en masse, issuers may be forced to rapidly sell T-bills, pushing up yields and destabilizing short-term funding markets.

- Conversely, surging stablecoin demand could drive large-scale T-bill purchases, lowering yields.

This bidirectional "liquidity shock" indicates that once stablecoin markets reach the scale of major money market funds, they will deeply penetrate traditional monetary policy and financial system operations, becoming core players in the "shadow money" ecosystem.

Conclusion

Stablecoins sit at the intersection of technological innovation, regulatory frameworks, and traditional monetary theory. They make money more programmable and accessible, offering a new paradigm for payments and clearing. At the same time, they challenge the delicate balance of modern financial systems—particularly the fractional reserve model and central banks’ control over money.

In short, stablecoins won’t directly replace commercial banks, but their presence continuously pressures the traditional banking system, forcing it to innovate faster.

As the stablecoin market grows, central banks and financial regulators must confront key challenges:

- How to coordinate shifts in global liquidity

- How to strengthen regulatory structures and inter-agency coordination

- How to introduce greater transparency and efficiency without damaging the money multiplier effect

Possible future paths for stablecoins include:

- Stricter compliance and regulation

- Fractional reserve hybrid models

- Integration with CBDC systems

These choices will not only shape the trajectory of digital payments but could even redefine the direction of global monetary policy.

Ultimately, stablecoins reveal a fundamental tension: the conflict between an efficient, programmable, full-reserve system and a leveraged credit mechanism that drives economic growth. Finding the optimal balance between "transactional efficiency" and "monetary creativity" will be a central challenge in the evolution of future monetary and financial systems.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News