Bitcoin Standard 2: Is the "Deflationary Trap" a "Century-Long Lie"?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Bitcoin Standard 2: Is the "Deflationary Trap" a "Century-Long Lie"?

Money is the measure of civilization, and a stable monetary standard determines the vitality of the economy and the degree of societal prosperity.

Author: Daii

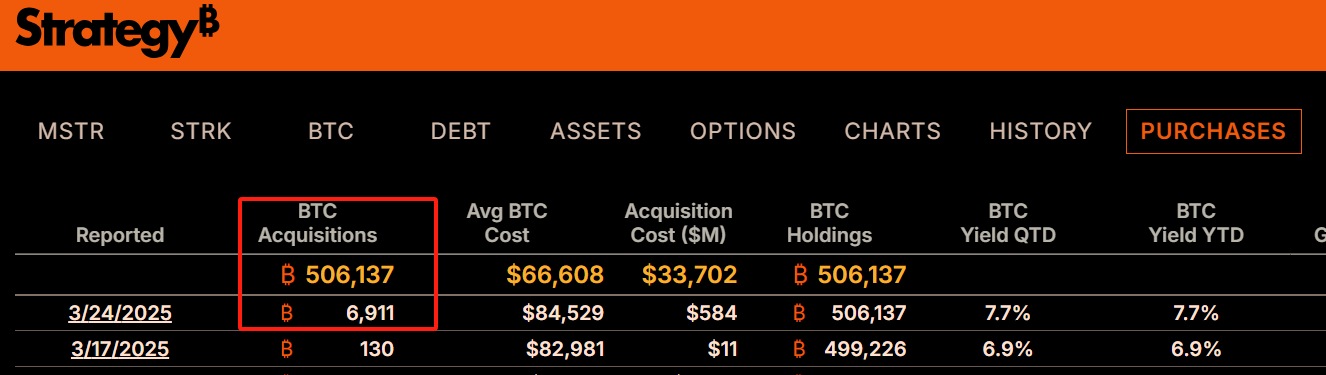

On March 24, Strategy (formerly MicroStrategy) made another major move—purchasing 6,911 bitcoins at an average price of $84,000, pushing its total bitcoin holdings past the 500,000 BTC milestone, with an average cost basis of $66,000. At the current market price of approximately $88,000 per BTC, the company now holds an unrealized gain of $22,000 on each bitcoin.

Clearly, at any point in time and across the global wave of cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin has remained the brightest star. Yet since its inception in 2009, it has never been free from controversy—especially within the economics community, where criticism of Bitcoin persists. One of the most frequently cited critiques comes from Nobel laureate Paul Krugman.

Krugman sharply argued that if an economy were to adopt Bitcoin as its monetary standard, its fixed supply would inevitably lead to a rigid money supply and thus trigger deflation. He warned that such a "deflationary trap" would encourage people to delay consumption, cause corporate profits to fall, spark waves of layoffs, and ultimately plunge the economy into a vicious cycle of recession. I explored this viewpoint in depth in my article *Bitcoin Should Be a Mirror for Us*.

Today, the idea of a "deflationary trap" has become one of the common justifications used by many nations resisting Bitcoin. But here's the critical question: Is this argument actually valid? Is deflation truly an unavoidable fate for Bitcoin—or is it merely a misunderstanding born from traditional economic paradigms confronting something new?

To answer this, we must first understand:

-

What is deflation?

-

How does deflation occur?

Only by thoroughly grasping these two questions can we properly assess whether Bitcoin and deflation are natural enemies—or whether their relationship has simply been misunderstood.

We’ve heard a lot about Bitcoin; but you may still find the concept of “deflation” somewhat unfamiliar. Fortunately, the book *The Bitcoin Standard* offers exactly the lesson we need.

1. What Is Deflation?

Deflation is short for “deflation of the currency.” In simple terms: “currency” refers to what we commonly call money. Currency deflation means there is less money circulating in the market.

To deeply understand deflation, we must start with its opposite—inflation—and discussing inflation requires understanding the concept of “money supply.” Only by clarifying what money supply really means can we grasp the true logic behind inflation and deflation.

Money supply is typically denoted by “M,” and categorized into multiple tiers based on liquidity. The most commonly used are M1 and M2.

M1, known as “narrow money,” includes cash (banknotes and coins) and demand deposits—funds that can be spent immediately, with very high liquidity. For example, the cash in your wallet or your mobile payment balance both fall under M1.

M2, called “broad money,” includes everything in M1 plus time deposits, savings accounts, and money market funds—assets that aren’t immediately spendable but can usually be converted into liquid cash with minimal delay or interest loss.

The key to inflation or deflation lies in the relationship between these money supply indicators (like M2) and the supply of goods and services.

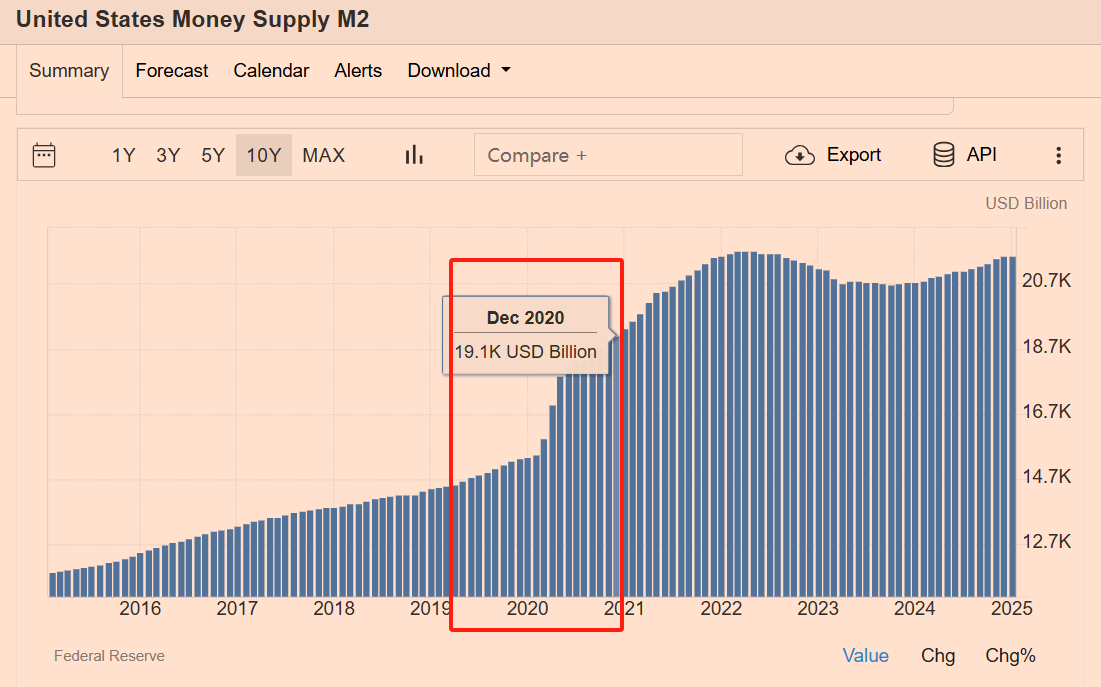

When the growth of money supply (e.g., M2) outpaces the growth of goods and services, too much money chases relatively limited products, driving up prices across the board—this is “inflation.” According to Federal Reserve data, after the 2020 pandemic, the U.S. implemented massive monetary easing policies, causing M2 to grow by a staggering 24% in just one year. This flood of money directly led to a 7% inflation rate in 2021—the highest in nearly 40 years—making consumers acutely aware of rapidly rising prices for daily necessities, food, and energy.

Deflation, on the other hand, is the reverse. When the growth rate of money supply falls below the growth rate of goods and services—or when money supply actually contracts—money becomes increasingly “scarce” in the market. As a result, the same amount of currency can buy more goods, leading to widespread price declines—this is “deflation.”

The most classic historical example of deflation is the Great Depression in the United States during 1929. At that time, numerous banks collapsed, causing sharp contractions in both M1 and M2. This dramatic reduction in money supply led directly to a liquidity crisis, falling prices, shrinking corporate profits, and massive layoffs—plunging the entire economy into a negative spiral. We’ll explore exactly how the Great Depression unfolded and how deflation occurred in more detail shortly.

In contrast, inflation resembles a “fever”—too much money overheating the economy, fueling speculative bubbles and eroding wealth—while deflation resembles a “chill,” freezing economic activity as people stop spending and businesses halt investment, gradually bringing economic life to a standstill.

Next, let’s examine the Great Depression of the 1930s—one of history’s most severe deflation-driven crises.

2. The Great Depression: A Terrifying Case of Deflation?

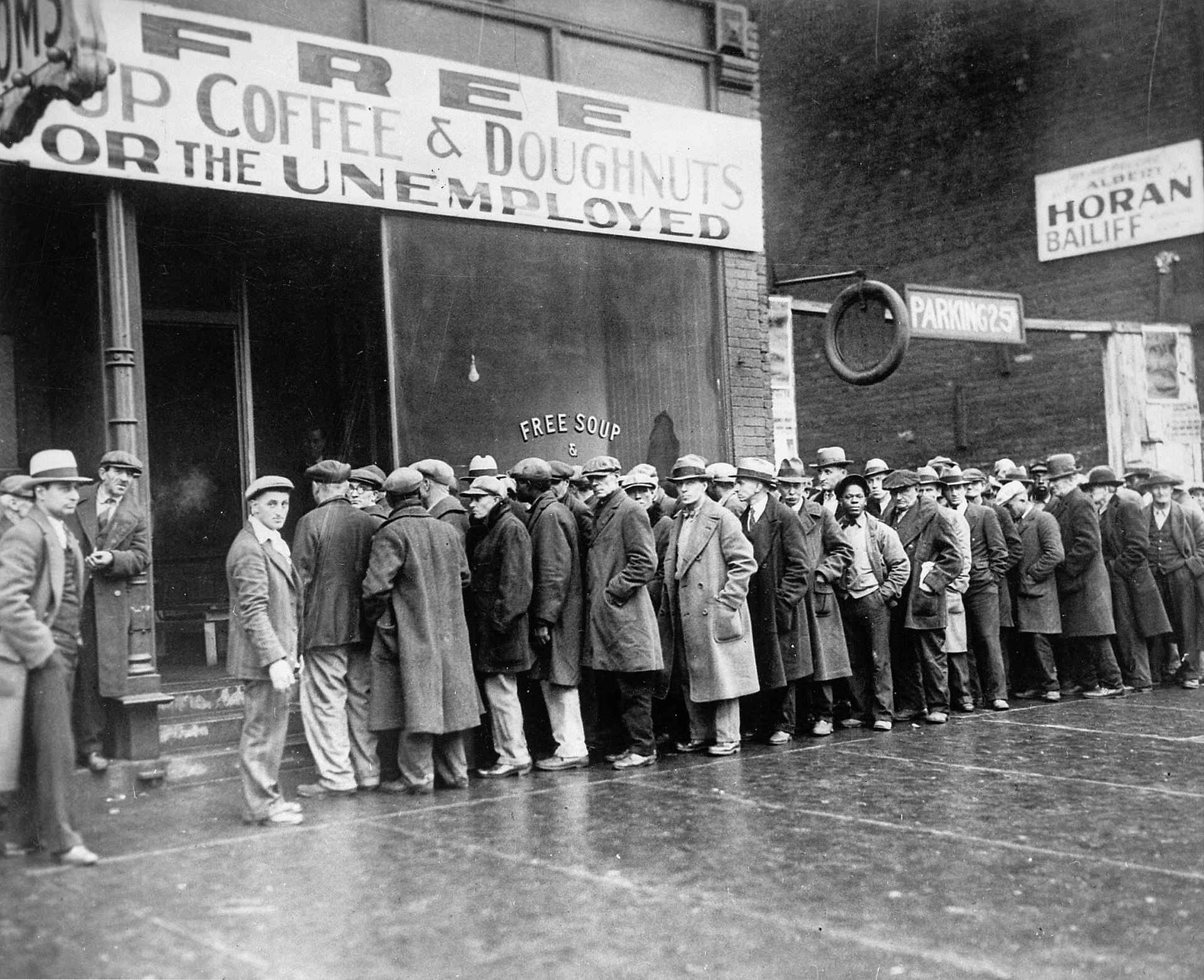

Whenever deflation is mentioned, people often picture the winter of economic recession—a society seemingly frozen in place.

The most immediate image that comes to mind is a black-and-white photograph from the early 1930s: unemployed workers lining up outside a soup kitchen in Chicago during the depths of the Great Depression in February 1931.

During that period, the U.S. experienced severe deflation, with prices plummeting like a broken kite. Historical data shows that from 1929 to 1933, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) dropped by about 25%. This means that $100 in 1929 had the purchasing power equivalent to roughly $133 today by 1933. That sounds beneficial—but the reality was far worse.

Why?

Because deflation doesn’t just mean lower prices—it paralyzes the entire economic cycle. Imagine if everyone expects prices to drop further tomorrow, so no one spends today. In 1929, U.S. retail sales plunged from $48.4 billion to just $25.1 billion by 1933—nearly halved. Plummeting consumption caused massive inventory buildup, profit collapses, and forced large-scale layoffs. This further eroded consumer confidence, pushing unemployment from 3.2% in 1929 to a staggering 24.9% in 1933—leaving one in four workers jobless. The economy spiraled downward into a bottomless abyss, struggling yet sinking ever deeper.

But now suppose I told you that deflation isn’t always terrifying—that sometimes, it can even be delightful. Would you find that strange?

3. The Great Boom: A Delightful Case of Deflation?

People often associate deflation with depression, but history shows that deflation doesn’t necessarily lead to economic decline—in fact, it can coexist with unprecedented prosperity. The clearest example is the late 19th century’s “Belle Époque” (The Beautiful Era), a golden age under the gold standard.

Indeed, similar phenomena existed even before the Belle Époque. For instance, during the Renaissance, Florence and Venice rapidly rose as Europe’s economic, artistic, and cultural centers—largely because they were among the first to adopt stable and reliable monetary standards.

3.1 Gold Coins and the Renaissance

In 1252, Florence issued the famous Florin gold coin. The Florin was historically significant—it was the first high-purity, reliable gold coin in Europe since the Aureus of ancient Rome’s Emperor Caesar. Each Florin weighed about 3.5 grams and contained 24-karat gold. Its consistent purity and fixed weight quickly made it the standard trade currency across Europe.

The reliability of the Florin dramatically elevated Florence’s status in the European economy and fueled the rise of banking. Florentine bankers, such as the famed Medici family, established branches across Europe, offering deposit, lending, remittance, and currency exchange services—laying the foundation for the modern banking system. With the Florin backing cross-border trade, merchants could conduct international business without fear of currency devaluation or exchange volatility.

Then in 1270, Venice followed Florence’s lead by minting its own Ducat gold coin, identical in specification and purity to the Florin. This reliable monetary standard quickly spread across the continent. By the end of the 14th century, over 150 countries and regions in Europe had issued gold coins modeled on the Florin. This monetary uniformity greatly simplified international trade and accelerated capital flows and wealth accumulation within Europe.

It was precisely within this stable monetary system built on gold that Florence became the epicenter of the Renaissance. Stable money not only drove economic prosperity but also created fertile ground for art and humanism. The Medici family used their vast banking wealth to sponsor artistic geniuses like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael. These masters could focus entirely on creation, producing masterpieces such as Michelangelo’s *David*, da Vinci’s *Mona Lisa*, and Brunelleschi’s dome of the Florence Cathedral—truly advancing human civilization.

However, the best illustration of deflationary prosperity is the late 19th-century Belle Époque. During this era, deflation and economic boom coexisted in a remarkable fusion—creating one of the most extraordinary golden ages in human history.

3.2 Deflationary Prosperity in the Belle Époque

The “Belle Époque” spanned roughly from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

The stable monetary systems built on gold not only enabled the brilliance of Renaissance-era Florence and Venice but also achieved a perfect blend of economic growth and technological innovation during the second half of the 19th century.

During this time, major world powers adopted a unified gold standard, making currency conversion extremely simple. Different national currencies were essentially different weights of gold. For example, the British pound was defined as 7.3 grams of gold, the French franc as 0.29 grams, and the German mark as 0.36 grams. Exchange rates were thus naturally fixed—for instance, 1 pound always equaled 26.28 francs and 24.02 marks. This straightforward mechanism made global trade as simple as measuring length, realizing the vision of true global free trade.

Under this gold standard, there was no interference from central bank monetary policy. How much money people held depended solely on individual needs—not manipulation by governments or central banks. The reliability of money encouraged saving and capital accumulation, accelerating industrialization, urbanization, and rapid technological progress.

Within this stable monetary environment, productivity surged. The Belle Époque witnessed numerous world-changing inventions:

-

Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876;

-

Carl Benz developed the first internal combustion engine car in 1885;

-

The Wright brothers achieved the first powered flight in 1903;

In 1870, the total length of U.S. railroads was about 50,000 miles; by 1900, it had expanded to 190,000 miles—completely transforming lifestyles and business models.

Medical breakthroughs were equally astonishing: heart surgery, organ transplantation, X-rays, modern anesthesia, vitamins, and blood transfusion technology all emerged during this era. These innovations not only boosted productivity but also significantly improved human living standards and lifespan.

The rise of petrochemical technology gave birth to essential materials like plastic, nitrogen fertilizer, and stainless steel—greatly increasing agricultural and industrial efficiency, making goods cheaper and more accessible.

As economist Ludwig von Mises put it: “The quantity of money is irrelevant; what matters is its purchasing power. People do not need more money—they need more purchasing power.”

Cultural and artistic flourishing also relied on a sound monetary system. Just as in Renaissance Florence and Venice, Paris, Vienna, and other European hubs during the Belle Époque saw a surge of artistic masters. Artists and thinkers benefited from low-time-preference investors who patiently funded creative work—fueling the rise of Neoclassicism, Romanticism, Realism, and Impressionism.

The reason the Belle Époque remains so nostalgically remembered isn’t just its unprecedented economic growth—it’s that it uniquely combined deflation with prosperity. Falling prices didn’t stall consumption; instead, people enjoyed higher quality lives with less money.

The evidence shows: deflation does not inevitably lead to economic collapse. So you might ask:

-

Why then did the deflation starting in 1929 lead to the Great Depression?

-

Why did the same deflation produce such different outcomes?

-

If deflation is not guilty, then who is?

Only by thoroughly examining the origins of the Great Depression can we uncover the real causes and answer these questions.

4. How Did the Great Depression Unfold Step by Step?

Return to the 1920s, and you’ll find a world seemingly overflowing with gold. The Great Depression began against this backdrop—and it all started with the Federal Reserve’s extremely loose monetary policy in the early 1920s.

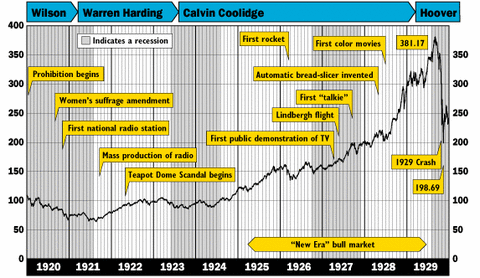

To help Britain stabilize the pound and prevent gold outflows, the Fed lowered its discount rate from 4% to 3% between 1924 and 1928. Though this appears a mere 1 percentage point drop, it dramatically stimulated demand for credit—like opening a floodgate, unleashing a torrent of dollars into the economy.

Under such extreme monetary looseness, investors found borrowing abnormally cheap—free lunches seemed everywhere. According to *The Bitcoin Standard*, from 1921 to 1929, the U.S. money supply grew by a staggering 68.1%, far outpacing the mere 15% increase in gold reserves.

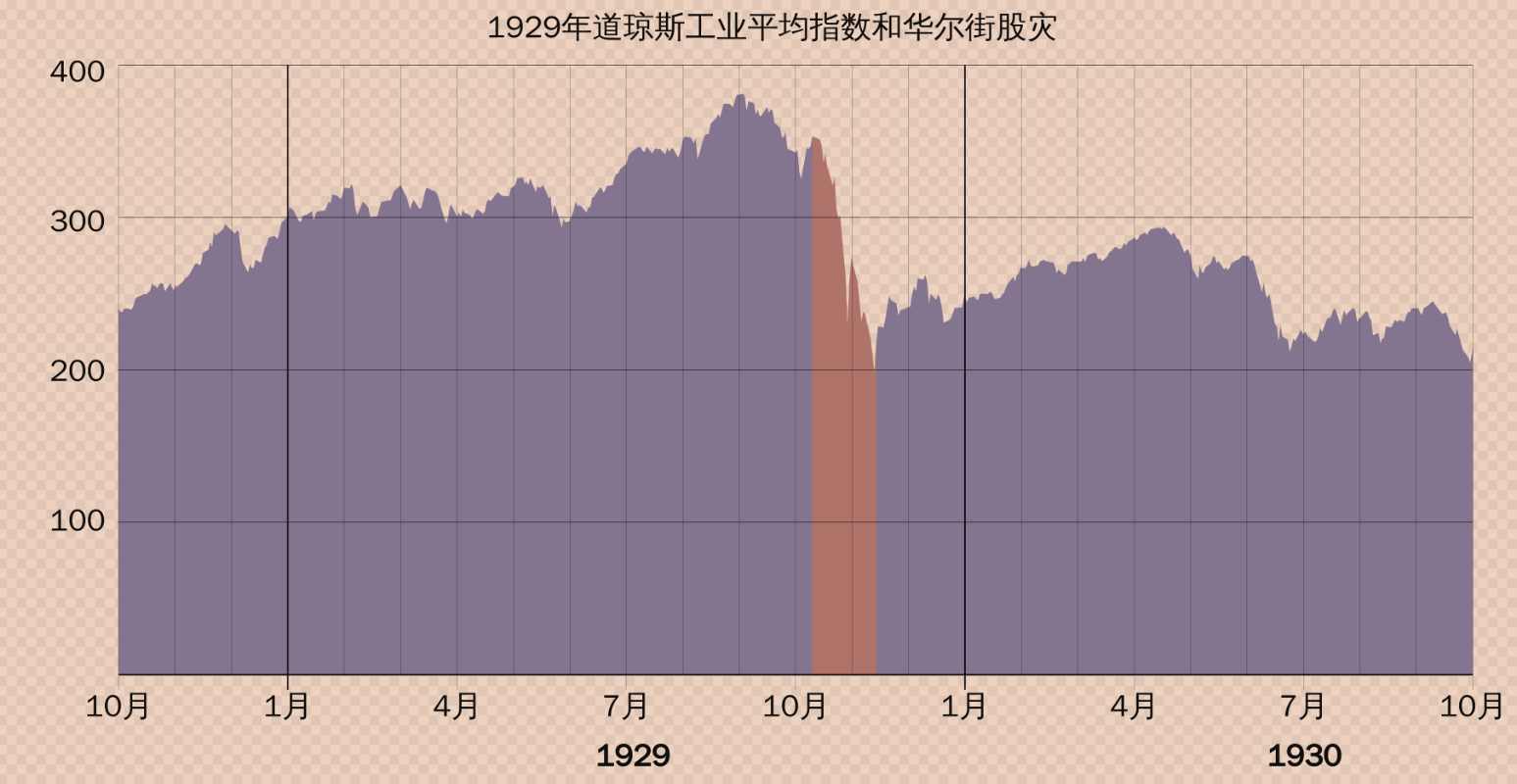

Vast amounts of cheap capital poured into the stock market. The Dow Jones Industrial Average skyrocketed from 63 in 1921 to 381 in September 1929—a more than 500% increase in eight years. Speculative frenzy reached incredible levels—even factory workers, taxi drivers, and housewives borrowed heavily to invest in stocks.

Economist Irving Fisher confidently declared on October 16, 1929, that the stock market had reached a “permanently high plateau,” believing prices would not fall. Just one week later, on October 24, 1929, the U.S. stock market began its catastrophic crash—bursting the bubble completely.

In fact, by late 1928, the Fed had already recognized the risk of asset bubbles and began tightening monetary policy by raising interest rates to cool the overheated economy.

But this sudden shift shocked markets: higher interest rates shattered the illusion of endless price gains, and the bubble burst rapidly. October 24, 1929—“Black Thursday”—marked the beginning of the stock market collapse.

After the stock bubble burst, all those cheap loans turned into crushing burdens. Banks couldn’t recover loans, cash flow dried up, and a wave of bank runs ensued.

At this point, the Fed should have actively injected liquidity into the banking system to prevent panic from spreading. Instead, it took a passive stance. Allowing thousands of banks to fail further destroyed public confidence. Total bank deposits fell by about one-third, and M2 money supply contracted by over 30%. Between 1929 and 1933, around 10,000 U.S. banks collapsed.

Of course, misguided government policies worsened the crisis. Presidents Hoover and Roosevelt pursued interventionist measures—fixing wages, imposing price controls—attempting to “freeze” the economy at pre-depression levels. For example, to prop up farm prices, the U.S. government absurdly resorted to burning crops—an especially grotesque act amid widespread hunger and poverty.

By now, you likely understand:

The deflation during the Great Depression wasn’t the natural kind seen in the Belle Époque—it was the result of central bank mismanagement.

Economist Milton Friedman argued that if the Fed had promptly increased the money supply, bank failures and runs could have been mitigated, preventing prolonged economic decline.

Yet the author of *The Bitcoin Standard* points out that Friedman overlooked the root cause: the U.S. economy had already been severely distorted by artificial monetary expansion in the 1920s. Simply injecting more money after the bubble burst wouldn’t fix deep structural imbalances—it would only make future crises more severe.

In other words, without the monetary expansion starting in 1921, there would have been no sudden contraction later—and no decade-long Great Depression.

But why did the U.S. expand its money supply in 1921 to help Britain? Was America really being altruistic?

5. Was the Great Depression Caused by American Altruism?

The Fed’s ultra-loose monetary policy in the early 1920s appeared aimed at helping the Bank of England prevent gold outflows and stabilize the pound—but this wasn’t purely altruistic. The U.S. also had clear self-interest at stake.

To understand this, we must return to the post-WWI economic landscape.

5.1 Britain’s Overreaching Ambition

Before WWI, London was the center of the global financial system, and the pound was the core currency for international trade and reserves. But the war devastated Britain’s economy. To finance war expenses, the Bank of England issued large amounts of unbacked currency, breaking the link between the pound and gold and causing wild fluctuations in its value.

After the war, Britain sought to restore London’s status as the global financial hub. In 1925, Chancellor Winston Churchill announced the return to the gold standard, pegging the pound back to its prewar level—4.86 pounds per ounce of gold. This seemingly wise decision, however, planted serious dangers for the British economy.

Why? Because Britain’s productive capacity and economic strength had declined significantly after the war. The pound no longer had its prewar purchasing power. Forcing a return to an overvalued exchange rate made British goods uncompetitive, devastating exports. Gold rapidly flowed from Britain to stronger economies like the U.S.

This is exactly what happened. Britain’s gold reserves plummeted after returning to the gold standard, creating a dire situation. If continued, Britain might have had to abandon the gold standard again—severely damaging the pound’s international credibility. This was unacceptable to the British government.

But why would the U.S. want to help Britain? Was America acting purely out of kindness?

No.

5.2 America’s Self-Interest: “When Lips Are Gone, Teeth Catch Cold”

At the time, the Fed and Wall Street elites had a clear strategic goal: to use this moment to gradually replace London as the global financial center. In other words, Wall Street was willing to temporarily sustain British financial stability through loose monetary policy to avoid a sudden collapse of the UK economy.

Why? Because if Britain’s economy collapsed suddenly, the entire European financial system might follow. That would be disastrous for the U.S. During WWI, America had extended massive loans to Europe—so European financial stability was vital. A stable British financial system would create better investment conditions for the U.S. in Europe.

Besides, helping Britain stabilize its finances aligned with long-term interests of Wall Street bankers. Many major U.S. banks had close ties with the City of London and held substantial assets and claims there. A sharp fall in the pound would drastically reduce the value of these holdings.

In short, American financiers didn’t want the British financial market to collapse prematurely—because it would jeopardize their massive investments in Britain.

5.3 The Unintended Consequences of Rate Cuts

Thus, for Britain—and for themselves—the Fed implemented a series of loose policies between 1924 and 1928, cutting the discount rate from 4% to 3%. Though seemingly minor, this effectively opened the floodgates, flooding the economy with cheap dollars. U.S. banks rapidly lent out this money, stimulating the economy and inflating asset prices—creating the illusion of prosperity in the 1920s.

This strategy worked in the short term. Britain’s gold outflow eased temporarily, the pound stabilized, and London’s financial collapse was delayed. But the problem was that this artificial intervention suppressed U.S. market interest rates, causing severe economic distortions.

Specifically, excessively low interest rates encouraged reckless investment by businesses and individuals, fueling speculation in real estate and stocks. From 1921 to 1929, the Dow surged over 500%, and property prices soared—eventually forming a massive asset bubble.

From a broader historical view, the Fed’s actions weren’t pure altruism, but a strategic move by American elites to advance their own financial dominance by assisting Britain. While it protected U.S. economic interests and asset security in Europe in the short run, it sowed far greater risks for the American economy.

History proved this short-sighted policy backfired. When the bubble burst in 1929, neither the Fed nor the U.S. government could prevent the crisis—instead, they plunged the economy into an unprecedented depression. The Great Depression was the direct result of prior artificial manipulation of money supply and interest rates.

The author of *The Bitcoin Standard* emphasizes that it was precisely the Fed’s actions in the 1920s that led to these catastrophic economic consequences.

Now we can finally see clearly:

-

Deflation itself isn’t frightening—the real danger lies in central banks arbitrarily manipulating money and interest rates.

-

Returning to our original question: the concern that Bitcoin’s fixed money supply would create a “deflationary trap” should now be clearly resolved.

6. Is the “Deflationary Trap” Merely a Man-Made Disaster?

Currency is widely accepted because it serves as a stable measure of value—a precise ruler that allows people to confidently calculate costs, revenues, and future returns in complex economic activities.

But the problem is that traditional fiat currencies lack this stability—their value can swing wildly due to central bank policies. The painful lessons of the 1929 Great Depression prove this: artificially manipulating money supply and interest rates destroys the very foundation of money as a stable measure of value. It is this man-made deflation—not deflation itself—that is truly catastrophic.

In contrast, if deflation results from rising productivity and technological progress—leading to naturally falling prices—such deflation is not destructive but profoundly beneficial. The “Belle Époque” and the Renaissance stand as prime examples of the brilliant achievements brought by such “natural deflation.”

Earlier, we discussed the industrial revolution during the deflationary late 19th century—let’s revisit it briefly:

From 1870 to 1900, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) fell by about 30% cumulatively—meaning prices declined at an average rate of roughly 1% per year.

U.S. steel production exploded from 20,000 tons in 1865 to 10 million tons by 1900;

Manufacturing output grew by over 500%.

This shows that gradual price declines were actually signs of economic prosperity—not harbingers of stagnation.

Take a more modern example: from 1980 to 2000, the U.S. tech industry boomed. Computer prices dropped nearly 90%, while performance improved thousands of times. Similarly, smartphone prices keep falling while functionality improves exponentially. Consumers don’t refrain from buying because “next year’s computer will be cheaper”—on the contrary, they continuously upgrade to better devices, because demand isn’t infinitely postponable.

In fact, this kind of “natural” deflation greatly benefits consumers and continuously improves living standards. Only “artificial” deflation leads to human tragedies like the Great Depression.

In essence, the “deflationary trap” is just a scare tactic—a justification to legitimize the manipulation of money’s value and, ultimately, to legally expropriate public wealth through monetary means.

Conclusion

When the dust of history settles, we clearly see that what truly threatens economic stability isn’t inflation or deflation—but the invisible hand of human manipulation over money. Money is the ruler of civilization; a stable monetary measure determines the vitality of an economy and the degree of societal prosperity.

Bitcoin emerges precisely to offer a value measure that cannot be arbitrarily altered. It gives us a form of money that requires no trust in human actors—a currency that truly returns to the essence of the market.

Bitcoin is not a deflationary trap. It is an escape route from man-made disasters, a natural path toward economic prosperity.

In the final analysis:

Deflation is not the crime; human manipulation is the culprit. With a stable measure of value, lasting prosperity follows.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News