The Origin of Money

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Origin of Money

Many types of wealth transfers, whether one-way or two-way, voluntary or involuntary, face transaction cost issues.

Written by: Nick Szabo

Translated by: Block unicorn

Abstract

The precursors of money, along with language, helped early modern humans solve cooperative problems that other animals could not—particularly how to achieve reciprocal altruism, kin selection, and reduced aggression. These ancestral forms of money shared very specific characteristics with non-fiat currencies—they were far more than mere symbolic objects or decorations.

Money

When England began colonizing America in the 17th century, it immediately encountered a problem: a shortage of metallic coinage [D94][T01]. The British vision was for American colonies to grow large quantities of tobacco and provide timber for their global navy and merchant fleets, then exchange these goods for supplies essential to maintaining colonial productivity. In practice, early colonists were expected to work for the company and spend their earnings at company stores. Investors and the Crown preferred this arrangement over paying farmers in metal coins so they could independently procure supplies and keep, well, some damn profit for themselves.

There was another option right under the colonists’ noses—but it took them years to recognize it: Native Americans already had their own form of money, vastly different from European conceptions. Indigenous peoples of the Americas had used currency for thousands of years, and it turned out to be highly useful to newly arrived Europeans—except for those prejudiced toward the idea that only coins bearing great men’s portraits constituted “real” money. Worse still, these New England natives used neither gold nor silver; instead, they utilized the most durable materials available in their environment: long-lasting parts of animal bones and shells. Specifically, they crafted beads (wampum) from shells of species like venus mercenaria into necklaces.

Wampum necklaces. During transactions, people would count out beads, remove them, and restring them into new necklaces. Native American wampum was sometimes also strung into belts or other ceremonial or commemorative items, symbolizing wealth or commitments to treaties.

These mollusks lived only in the sea, yet the beads circulated deep inland. Shell money appeared in diverse forms among tribes across the continent. The Iroquois, who never visited shell habitats, amassed more wampum treasure than any other tribe. Only a few tribes, such as the Narragansett, specialized in manufacturing wampum, but hundreds of tribes—mostly hunter-gatherers—used it as currency. Wampum necklaces varied greatly in length, with bead count proportional to length. Necklaces could always be cut or joined to match the price of goods.

Once colonists overcame their skepticism about the source of monetary value, they began actively buying and selling wampum. The term for shellfish in American vernacular became synonymous with "money." The Dutch governor of New Amsterdam (now known as "New York") borrowed a large sum—paid in wampum—from the English-American Bank. Later, British authorities reluctantly acquiesced, and between 1637 and 1661, wampum became legal tender in New England, providing colonists with a highly liquid medium of exchange and fueling trade prosperity.

But as Britain shipped more metal coins to America and Europeans applied mass production techniques, shell money gradually declined. By 1661, British authorities conceded defeat, agreeing to pay in royal metal coinage—gold and silver—and that year, wampum ceased to be legal tender in New England.

Yet in 1710, North Carolina again adopted wampum as legal tender. It continued as a medium of exchange into the 20th century. However, due to Western harvesting and manufacturing advances, the value of wampum rose a hundredfold before, like gold and silver jewelry in the West, it transitioned from carefully crafted money into mere decoration with the arrival of the metallic age. In American speech, shell money became an odd archaic term—after all, “100 shells” evolved into “100 dollars.” “Shelling out” originally meant paying with shells, later shifted to payment in metal coins or paper, and now refers to checks or credit cards [D94].

We didn’t realize this touched upon the origins of our species itself.

Collectibles

Beyond shells, money on the American continent took many forms. Hair, teeth, and numerous other items were widely used as media of exchange (their shared properties will be discussed later).

Twelve thousand years ago, in what is now Washington State, Clovis people crafted remarkable long flint blades. The only issue: these blades broke too easily—they were completely unsuitable for cutting. These flints were made “purely for entertainment,” or for purposes entirely unrelated to utility.

Later, we’ll see that this apparent frivolity likely played a vital role in their survival.

American natives were neither the first to craft ornamental yet useless flint tools, nor the first to invent shell money. Nor were Europeans, despite their extensive historical use of shells and teeth as currency—not to mention cattle, gold, silver, weapons, and others. Asians used all these and even government-issued fake axes (translator's note: likely referring to "knife money"), but they also adopted such tools (shells). Archaeologists have discovered shell necklaces dating back to the early Paleolithic era—perfect substitutes for the currencies used by Native Americans.

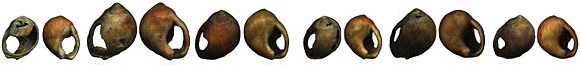

Pea-sized beads made from Nassarius kraussianus seashells. These snails live in estuaries. Found in Blombos Cave, South Africa. Dated to 75,000 years ago.

In the late 1990s, archaeologist Stanley Ambrose discovered necklaces made from ostrich eggshells and shell fragments in a stone shelter within Kenya’s Great Rift Valley. Using argon-argon (40Ar/39Ar) dating, he determined they were at least 40,000 years old. Animal tooth beads found in Spain date to the same period. Perforated shells from the early Paleolithic have been unearthed in Lebanon. Recently, complete shells prepared for bead-making were found in Blombos Cave, South Africa, dating back 75,000 years!

Ostrich eggshell beads, found in East Africa’s Great Rift Valley, Kenya. 40,000 years old. (Photo courtesy of Stanley Ambrose)

As anatomically modern humans migrated into Europe, shell and tooth necklaces appeared there around 40,000 years ago. They reached Australia over 30,000 years ago. In every case, craftsmanship was highly sophisticated, suggesting such practices predate even the earliest archaeological evidence. The origin of collectibles and adornments likely lies in Africa—the birthplace of Homo sapiens. The act of collecting and crafting necklaces must have conferred significant survival advantages, given their luxury nature: requiring immense skill and time to produce during eras when humans teetered on starvation.

Essentially all human cultures—even those without large-scale trade or modern monetary systems—create and appreciate jewelry and artifacts whose artistic or heritage value far exceeds practical utility. Humans collect shell necklaces and other forms of jewelry purely for pleasure. To evolutionary psychologists, saying “humans do something just for pleasure” isn't an explanation—it poses a question. Why do so many find the luster of collectibles and jewelry pleasurable? More directly: what evolutionary advantage did this pleasure confer?

A necklace found in a burial site at Sungir, Russia, 28,000 years old. Features interlocking, interchangeable beads. Each mammoth ivory bead may have required one to two hours of labor.

Evolution, Cooperation, and Collectibles

Evolutionary psychology stems from a key mathematical insight by John Maynard Smith. Smith adapted population models of co-evolving genes (from established population genetics) to show that genes can encode behavioral strategies—optimal or suboptimal solutions to simple strategic problems ("games" in game theory).

Smith demonstrated that competitive environments can be modeled as strategic games, where genes that achieve Nash equilibria in these games are more likely to survive and propagate across generations. These games include the Prisoner’s Dilemma (the archetype of cooperation problems) and the Hawk-Dove game (the paradigm of aggressive strategies).

The crucial point in Smith’s theory is that these strategic games, though played out in physical organisms, fundamentally occur between genes—the competition for gene propagation. Genes (not necessarily individuals) influence behavior, appearing to exhibit limited rationality (encoding optimal strategies within biological constraints) and “selfishness” (borrowing Richard Dawkins’ metaphor). Gene-driven behaviors are adaptations to competitive pressures expressed through organismal form. Smith termed these evolving equilibria “evolutionarily stable strategies.”

Classical theories based on individual selection—such as sexual and kin selection—were subsumed into this broader model, which revolutionarily placed genes, not individuals, at the center of evolutionary theory. Hence Dawkins’ often-misunderstood analogy: the “selfish gene” to describe Smith’s framework.

Few species surpass even Paleolithic humans in cooperative capacity. In some cases—like ants, termites, and bees—animals cooperate among kin because doing so helps replicate their shared “selfish genes.” In rare instances, cooperation occurs between non-kin, termed “reciprocal altruism” by evolutionary psychologists. As Dawkins described, unless exchanges are simultaneous, one party can cheat (and often does). This leads to the typical outcome in the Prisoner’s Dilemma: while mutual cooperation yields better results, defection allows one party to exploit the other. In a population of defectors and suckers, defectors always win (making cooperation difficult). However, some animals achieve cooperation through repeated interactions using a “tit-for-tat” strategy: cooperate first, continue cooperating unless the opponent defects, then retaliate. The threat of reprisal sustains cooperation.

Overall, interspecies cooperation in the animal world remains severely limited. A major constraint is the relationship between parties: at least one side must be somewhat physically bound to the other. The most common example is parasites and hosts evolving into symbionts. When parasite and host interests align, symbiosis becomes preferable (e.g., parasites begin benefiting the host); if they enter a tit-for-tat dynamic, they evolve into symbionts, aligning their reproductive interests. They become like a single organism. Yet exploitation often persists alongside cooperation. This resembles a human institution we’ll analyze later: tribute.

Even rarer are non-kin animals sharing a body and becoming symbiotic. One elegant example Dawkins cites is cleaner fish, which swim into host fish mouths to eat bacteria, improving host health. Host fish could cheat—eat the cleaners after service—but they don’t. Both parties are mobile and free to leave. But cleaner fish evolved strong territorial instincts and distinctive, hard-to-fake stripes and dances—akin to counterfeit-proof trademarks. Hosts know where to find cleaning services and understand that cheating means finding new cleaners—a high-cost endeavor. Thus, both cooperate without deception. Additionally, cleaner fish are tiny, so eating one provides less benefit than ongoing cleaning services.

Another highly relevant case is vampire bats. True to name, they feed on mammalian blood. The interesting part: feeding success is highly unpredictable—sometimes gorging, sometimes starving. Lucky (or skilled) bats thus share blood with less fortunate ones: donors regurgitate blood, recipients gratefully consume it.

Most exchanges involve kin. Of 110 documented cases observed by the patient biologist G.S. Wilkinson, 77 involved mothers feeding offspring, and most others involved genetic relatives. Yet a few cases couldn’t be explained by kin altruism. To explain this reciprocity, Wilkinson mixed bats from two groups into one colony. He then observed that, with rare exceptions, bats primarily aided old friends from their original group.

This cooperation requires long-term relationships—frequent interaction, mutual recognition, and tracking of past behaviors. Caves help confine bats into enduring relationships, enabling such cooperation.

We’ll see that humans, like vampire bats, adopted high-risk, unstable subsistence methods and share surpluses with non-kin. Indeed, they’ve achieved this far beyond bats—and understanding how is the focus of this article. Dawkins said, “money is a formal token of delayed reciprocal altruism,” but then abandoned this fascinating idea. That task falls to us.

In small human groups, public reputation can substitute for individual retaliation, enabling cooperative delayed exchanges. However, reputation systems face two major challenges: difficulty identifying who did what, and assessing the value or damage caused by actions.

Recognizing faces and recalling associated favors poses cognitive burdens, yet most humans manage it relatively easily. Face recognition is straightforward, but remembering specific helpful acts when needed is harder. Recalling detailed value delivered in a favor is even harder. Disputes and misunderstandings are inevitable—or so difficult they prevent help altogether.

The valuation problem—measuring value—is pervasive. Humans face it in every transaction system: gift exchange, barter, money, credit, employment, or market trade. It’s equally critical in extortion, taxation, tribute, and judicial penalties. Even animal reciprocal altruism hinges on it. Imagine monkeys helping each other—one offers fruit in exchange for back scratching. Mutual grooming removes lice and fleas unreachable by oneself. But how many grooming sessions equal how many fruits for both to perceive it as “fair” rather than exploitative? Is 20 minutes of grooming worth one or two fruits? How large a fruit?

Even simple “blood-for-blood” exchanges are more complex than they appear. How does a bat assess the value of received blood? By weight, volume, taste, satiety? Other factors? This measurement complexity exists identically in monkey “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” trades.

Despite abundant potential trading opportunities, animals struggle with value measurement. Even the basic pattern—remembering faces linked to favor histories—poses a significant barrier to developing reciprocity, because establishing precise initial consensus on favor value is difficult.

Yet the stone toolkits left by Paleolithic humans seem overly complex for our brains to comprehend. (Translator’s note: If they’re so complex to modern minds, what kind of cooperation enabled their creation, and for what purpose?)

Tracking favors related to these stones—who made what quality tool for whom, who owes whom what—could become extremely complex across tribal boundaries. Moreover, countless organic goods and ephemeral services (e.g., beauty treatments) left no trace. Even mentally storing a fraction of traded items and services becomes increasingly difficult as numbers grow, eventually impossible. If cooperation occurred between tribes—as archaeological records suggest—it becomes even harder, since hunter-gatherer tribes were typically highly hostile and distrustful.

If shells, furs, gold, etc., can be money—if money isn’t merely coins or state-issued fiat notes, but many things—what then is money’s essence?

And why did humans, often on the brink of starvation, spend so much time making and admiring necklaces they could have spent hunting and gathering?

Carl Menger, the 19th-century economist, first described how money naturally evolves inevitably from numerous barter transactions. Modern economics tells a similar story.

Barter requires coincidence of wants. Alice grows walnuts and needs apples; Bob grows apples and wants walnuts. They live nearby, and Alice trusts Bob enough to wait from walnut harvest to apple harvest. If all conditions align, barter works. But if Alice grows oranges, even if Bob wants them, it fails—oranges and apples can’t grow in the same climate. If Alice and Bob distrust each other and can’t find a third party to mediate or enforce contracts, their desires go unmet.

More complex issues arise. Alice and Bob cannot fully guarantee future delivery of walnuts or apples—Alice might keep the best walnuts for herself, selling inferior ones (Bob might do the same). Comparing quality—especially of different goods—is harder, particularly when one good exists only in memory. Neither can predict events like crop failure. These complexities drastically increase the difficulty of ensuring delayed reciprocal exchanges truly benefit both parties. The longer the delay and greater the uncertainty between initial and return transactions, the higher these costs.

Another related issue (engineers might recognize): barter “doesn’t scale.” With few goods, barter works, but its cost rises with volume until prohibitively expensive. With N goods and services, a barter economy needs N² prices. Five goods yield 25 relative prices—manageable; 500 goods yield 250,000 prices—far exceeding human cognitive capacity. With money, only N prices are needed—500 goods require 500 prices. Money then serves as both medium of exchange and unit of account—provided its own price doesn’t exceed memorization limits or fluctuate too frequently. (This latter issue, combined with implicit insurance “contracts” and lack of competitive markets, may explain why prices typically evolve slowly rather than being set via recent negotiations.)

In short, barter requires coincidence of supply (or skills), preferences, timing, and low transaction costs. Its transaction costs grow faster than the number of goods. Barter is better than no trade and was widespread, but compared to monetary trade, it remains highly constrained.

Prior to large trade networks, primitive money existed for a long time. But money served an even more crucial earlier function: dramatically improving efficiency in small barter networks by reducing credit needs. Complete preference coincidence is far rarer than intertemporal coincidence. With money, Alice can gather blueberries for Bob this month, and Bob can hunt large game for Alice six months later—without tracking debts or trusting memories and honesty. A mother’s major investment in child-rearing can be protected by gifting counterfeit-proof valuables. Money transforms division-of-labor dilemmas from prisoner’s dilemmas into simple exchanges.

Primitive currencies used by hunter-gatherer tribes looked nothing like modern money and served different cultural roles. Primitive money may have had functions limited to small transaction networks and local institutions (discussed later). Thus, I argue calling them “collectibles” rather than “money” is more appropriate. Anthropological literature calls them “money”—a definition broader than state-issued paper or coin but narrower than our “collectibles” or vaguer “valuable items” (which includes non-collectible valuables).

The rationale for using “collectibles” instead of other terms will emerge below. Collectibles possess very specific attributes—not mere decoration. While specific collectibles and valued traits vary culturally, they’re never arbitrary. Their primary, ultimate evolutionary function is serving as media for storing and transferring wealth. Some collectibles, like necklaces, resemble modern money closely—so much that even we (moderns in trade-friendly societies) can grasp their use. I occasionally use “primitive money” interchangeably with “collectibles” when discussing pre-metallic wealth transfer.

Gains from Trade

Individuals, clans, and tribes voluntarily trade because both parties expect gains. Their valuations may change post-trade—through experience with goods/services (altering standards). But at transaction time, while their valuations may not perfectly match objective values, their judgment of mutual benefit is generally accurate. Especially in early intertribal trade—limited to high-value items—parties had strong incentives to judge accurately. Thus, trade almost always benefits all. In value creation, trade rivals physical production.

Because individuals, clans, and tribes differ in preferences, abilities to satisfy them, and self-knowledge of skills/preferences/outcomes, they can always gain from trade. Whether transaction costs are low enough to make trade worthwhile is another matter. Today, far more trade occurs than in most past eras. Yet, as we’ll discuss, certain trades have always justified transaction costs—even tracing back to the dawn of Homo sapiens.

Lower transaction costs benefit more than just voluntary spot trades—a crucial point for understanding money’s origin and evolution. Family heirlooms serve as collateral, eliminating credit risk in delayed exchanges. The ability to extract tribute from defeated tribes benefits victors immensely—this capability, like trade, gains from the same transaction-cost-reducing technologies. Arbitrators assessing damages from norm violations, kin arranging marriages—all benefit similarly. Relatives inheriting timely, peaceful wealth transfers clearly benefit from durable, independent wealth storage. Even non-commercial aspects of human life in modern culture gain as much or more from transaction-cost-reducing technologies than trade itself. None predates or surpasses primitive money—collectibles—in efficiency, importance, or antiquity.

After Homo sapiens replaced Neanderthals (H. sapiens neanderthalis), human populations surged. Artifacts from Europe, 35,000–40,000 years old, indicate sapiens increased environmental carrying capacity tenfold—population density rose ten times. Moreover, newcomers had time to create the world’s earliest art—beautiful cave paintings, exquisite sculptures—and necklaces of shells, teeth, and eggshells.

These weren’t useless decorations. New, efficient wealth-transfer mechanisms—enabled by these collectibles and possibly advanced language—created novel cultural tools that likely contributed significantly to increased carrying capacity.

As newcomers, sapiens had brain sizes comparable to Neanderthals, softer bones, and weaker muscles. Their hunting tools were more refined, but until 35,000 years ago, tools were broadly similar—nowhere near twice as efficient, let alone ten times. The greatest difference may lie in wealth-transfer tools created and enhanced by collectibles. Sapiens derived pleasure from collecting shells, crafting and displaying jewelry, and trading them. Neanderthals did not. Perhaps due to this mechanism, sapiens survived the vortex of human evolution tens of thousands of years ago, emerging on Africa’s Serengeti Plain.

We should examine how collectibles reduce transaction costs—across voluntary inheritances, reciprocal trade and marriage, to involuntary judgments and tributes.

All forms of value transfer occurred in many prehistoric cultures, possibly since Homo sapiens’ inception. Benefits from life-event-based wealth transfers were so substantial they outweighed high transaction costs. Compared to modern money, primitive money circulated very slowly—changing hands only a few times in an ordinary person’s lifetime. Yet a durable collectible—a “heirloom” today—could remain intact for generations, gaining significant value with each transfer—often enabling otherwise impossible exchanges. Tribes thus invested vast effort in seemingly pointless manufacturing and searching for suitable new materials.

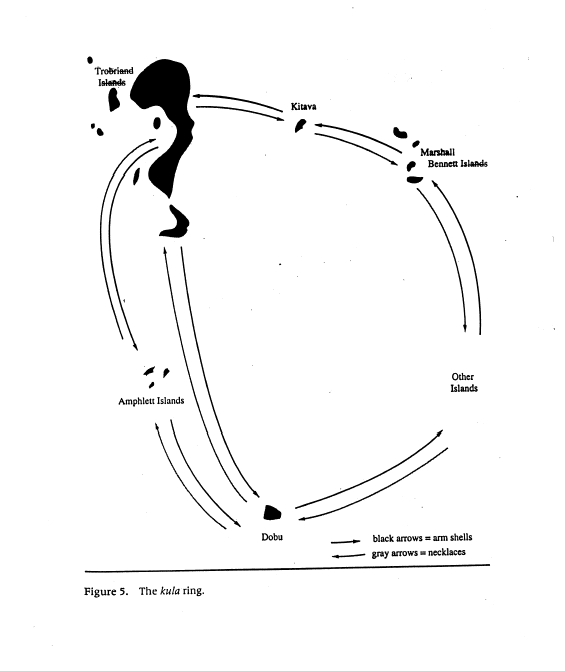

Kula Ring

Pre-colonial Kula trade network in Melanesia. Kula functioned as “very powerful” money and a repository of stories and legends. Tradable goods (mostly agricultural) ripened in different seasons, making barter impractical. Kula collectibles possessed unforgeable, high intrinsic value, were wearable and transferable—solving the double coincidence of wants. Due to this, a bracelet or necklace gained value exceeding production cost after several trades, circulating for decades. Legends about previous owners further provided upstream credit and liquidity information. In Neolithic cultures, circulating collectibles (usually shells) were often irregular but served similar purposes.

Kula bracelet (mwali)

Kula necklace (bagi)

For any tool primarily serving wealth transfer, we can ask:

-

Must two events (production and use of traded items) coincide in time? How severely does the impossibility of such coincidence hinder wealth transfer?

-

Can wealth transfer form a complete cycle solely via this tool, or does it require additional mechanisms? Studying actual money circulation patterns is crucial to understanding money’s emergence. For most human prehistory, broad, repetitive monetary circulation didn’t exist and couldn’t. Without full, recurring cycles, collectibles wouldn’t circulate or hold value. A collectible must facilitate enough transactions to amortize its production cost, justifying its creation.

We first examine the wealth transfer we know best and find economically most important today—trade.

Hunger Insurance

Bruce Winterhalder observed occasional food-sharing patterns among animals: tolerated theft, production/begging/opportunism, risk-sensitive foraging, reciprocal altruism as byproduct, delayed reciprocity, non-spot exchange, and other patterns (including kin altruism). Here, we focus on risk-sensitive foraging, delayed reciprocity, and non-spot exchange. We argue replacing delayed reciprocity with food-collectible exchanges enhances food sharing. This reduces risks from variable food supplies while avoiding most insurmountable problems of delayed reciprocity between bands. We’ll later address kin altruism and theft (forgiven or not) in broader context.

Food has higher value to the hungry than the sated. If a desperate, starving person can save their life with their most valuable possession, isn’t months of labor spent on that treasure worthwhile? People usually value their lives more than heirlooms. Thus, collectibles, like fat, provide insurance against food shortages. Local famines can be alleviated in two ways: direct food provision, or rights to forage and hunt.

However, transaction costs are generally prohibitive—warfare is more common than trust between groups. Starving groups often simply starve. But if transaction costs can be lowered by reducing intergroup trust requirements, food worth a day’s labor to one group might equal months of labor to a starving tribe—enabling mutually beneficial trade.

As argued here, small-scale, highly valuable trades emerged in many cultures during the Upper Paleolithic with the advent of collectibles. Collectibles substituted for the long-term trust relationships otherwise necessary (but absent). If tribes or individuals already shared long-term interaction and trust, credit extension without collateral would greatly stimulate delayed barter. Yet such high trust is unimaginable—due to the aforementioned problems with reciprocal altruism models, confirmed by empirical evidence: most observed hunter-gatherer intergroup relations are highly tense. For most of the year, hunter-gatherer bands disperse into small groups, occasionally aggregating like medieval fairs for weeks annually. Despite lacking trust, important product trades—like those depicted—almost certainly occurred among large-game-hunting tribes in Europe and nearly everywhere else, including America and Africa.

The scenario illustrated is theoretical, but its absence would be surprising. While many Paleolithic Europeans favored shell necklaces, inland dwellers often used teeth. Flint, axes, furs, and other collectibles likely served as media of exchange.

Reindeer, bison, and other prey migrate at different annual times. Different tribes specialized in hunting different prey—over 90% to 99% of remains in European Paleolithic sites belong to single species. This suggests seasonal specialization within tribes, possibly complete specialization per tribe per prey type. Achieving this requires members to become experts in prey behavior, migration, and specialized hunting tools/techniques. Recent observations confirm some tribes specialize. Certain North American Indian tribes specialized in bison, antelope, or salmon. In northern Russia and Finland, many tribes—including the Lapps—still herd only reindeer.

Large, fearless wild animals no longer exist. In the Paleolithic, they were either driven extinct or learned to fear humans and projectile weapons (i.e., bows). Yet for most of the sapiens era, wildlife abounded, and expert hunters easily captured them. According to our trade-survival theory, specialization was likely higher then, when vast herds of large prey (horses, bison, elk, reindeer, giant sloths, mastodons, mammoths, zebras, elephants, hippos, giraffes, musk oxen, etc.) roamed North America, Europe, and Africa. This intertribal hunting specialization aligns with European Paleolithic archaeological evidence (though not definitively proven).

Migratory groups following prey frequently interacted, creating abundant trade opportunities. American Indians preserved food via drying and pemmican-making—lasting months but rarely a full year. Such food traded for leather, weapons, and collectibles, typically during annual trade gatherings.

Migratory herds pass through territories only twice yearly, often with one- to two-month gaps; without alternative protein sources, specialized tribes would starve. Only trade enables the high specialization reflected in archaeological evidence. Thus, even seasonal meat exchange justifies collectibles.

Necklaces, flint, and other monetary items circulated in closed loops, with collectible quantity roughly matching traded meat volumes. Note: if our constructed collectible-cycle theory holds, one-way beneficial trade isn’t sufficient. We must identify closed, mutually beneficial trade cycles where collectibles continuously circulate, amortizing production costs.

Archaeological evidence shows many tribes specialized in hunting single large animals. Hunters at least seasonally pursued different prey (intra-tribal seasonal division); with extensive trade, entire tribes might hunt only one prey annually (inter-tribal complete division). While specializing grants huge production gains, these vanish if the tribe goes months without food.

Trade between two complementary tribes could double total food supply. But on the Serengeti and Eurasian steppes, over ten animal types (not two) migrate. Thus, for a specialized tribe, tradable meat multiplies beyond doubling. Crucially, extra meat arrives when needed.

Thus, even the simplest trade cycle—two prey types and two offset, complementary exchanges—provides participants at least four gains (sources of “surplus”):

-

Eating meat during formerly starvation-prone seasons;

-

Increased total meat supply—they can sell excess meat they can’t consume or store, preventing waste;

-

Dietary variety, enhancing nutrition;

-

Higher productivity from hunting specialization.

Producing or preserving collectibles to exchange for food isn’t the only famine insurance. More commonly (especially where large-game hunting isn’t feasible), transferable hunting rights on territory suffice. This is observable in surviving hunter-gatherer cultures.

South Africa’s !Kung San, like all surviving hunter-gatherers, inhabit marginal lands. Unable to specialize, they rely on scarce resources. Thus, they may poorly represent ancient hunter-gatherer cultures or primordial Homo sapiens (who seized fertile lands and prime hunting routes from Neanderthals, pushing them to margins much later). Yet despite harsh conditions, !Kung use collectibles in trade.

Like most hunter-gatherers, !Kung spend most of the year in small, dispersed bands, aggregating briefly with others. Gatherings function as multifunctional markets—facilitating trade, alliance-building, relationship reinforcement, and marital exchanges. Preparations involve crafting trade items—some practical, mostly collectibles. This system, called !Kung hxaro, involves extensive ornament trade, including ostrich eggshell necklaces—strikingly similar to 40,000-year-old African artifacts.

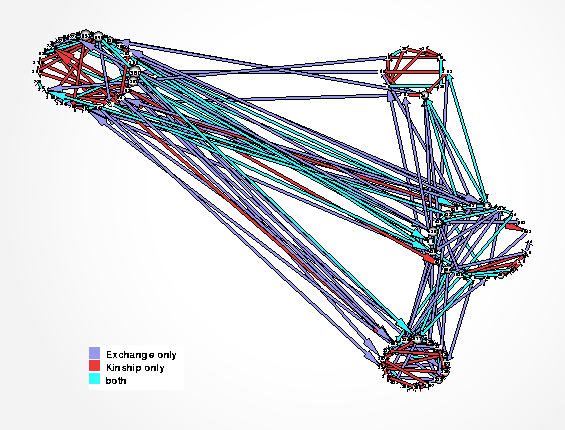

Pattern of hxaro exchange system and kinship among neighboring !Kung tribes

Necklace used in hxaro exchange

!Kung trade one major item with collectibles: abstract rights to enter other groups’ territories for foraging/hunting. This trade intensifies during local food scarcity, allowing relief via neighbors’ lands. !Kung mark territories with arrows; unauthorized entry equals declaration of war. Like intergroup food trade, purchasing foraging rights with collectibles constitutes “hunger insurance” (per Stanley Ambrose).

While anatomically modern humans possess conscious thought, speech, and planning, engaging in trade requires minimal sophisticated cognition or language, and even less planning. Tribal members needn’t infer trade’s broader benefits. Creating such tools only requires following instincts to pursue items with certain properties (as indirectly observed in accurate property assessment). This applies variably to other institutions we’ll discuss—they evolved, weren’t consciously designed. No participant explains these institutions via evolutionary function; instead, diverse myths motivate behaviors, serving more as direct incentives than theories of origin/purpose.

Direct evidence of food trade vanished long ago. Future discoveries might compare hunting patterns in one tribe versus consumption patterns in another—though identifying tribal/kin boundaries poses the main challenge. According to our theory, such intertribal meat exchange should have been widespread during the Upper Paleolithic, coinciding with large-scale specialized hunting.

Now, we have indirect evidence: the transfer of collectibles themselves. Fortunately, the durability required for collectibles matches archaeological preservation—allowing discovery millennia later.

Intergroup relations were predominantly distrustful, often violent. Only marriage or kinship enabled limited, occasional trust. Though collectibles could be worn or hidden in secret caches, weak property protection meant they had to amortize production costs in few transactions. Thus, trade wasn’t the sole wealth-transfer form—possibly not even primary—during humanity’s long prehistory, when transaction costs prevented markets, firms, and other economic institutions we take for granted. Beneath our grand economic institutions lie older ones involving wealth transfer—setting Homo sapiens apart from other animals. Now we turn to the most fundamental form—one humans take for granted, animals seemingly lack: inheritance.

Cross-Death Kin Altruism

Temporal and spatial coincidence of supply and demand is exceedingly rare—preventing most familiar trade types and trade-based institutions today. Triple coincidence—aligning supply with major clan events (new families, death, crime, victory/defeat)—is even rarer. Thus, clans and individuals greatly benefited from timely wealth transfers during such events. Such transfers wasted less, involving only durable wealth-storage items, not consumables or functional tools. The need for durable, universal wealth-storage items often exceeded the need for transaction media. Furthermore, institutions like marriage, inheritance, dispute resolution, and tribute may predate intertribal trade and involve greater wealth transfers. Thus, these institutions more powerfully drove primitive money’s emergence.

In most hunter-gatherer tribes, transferred wealth appears trivial to us “fat-cat” moderns: wooden utensils, flint and bone tools, weapons, shell necklaces, even hats, or in colder climates, moss-covered furs. Sometimes all were wearable. These diverse items constituted hunter-gatherer wealth—equivalent to our real estate, stocks, and bonds. For them, tools and warm clothing were survival necessities. Many transferred items were highly valuable collectibles—usable against hunger, purchasing mates, or saving lives in war/defeat.

Transferring survival capital to descendants gave Homo sapiens an edge over other animals. Skilled tribe members or clans could convert surplus consumables into lasting wealth (especially collectibles)—trades occurring sporadically but accumulating over lifetimes. Temporary adaptive advantages thus became permanent advantages for offspring.

Another wealth form (undetectable to archaeologists) was office. In many hunter-gatherer tribes, social status surpassed tangible wealth in value. Status included chieftain, war leader, hunting captain, members of long-term intertribal trade partnerships, midwives, religious leaders. Often, collectibles symbolized not just wealth, but tribal responsibility and rank. Upon a status-holder’s death, successors must be swiftly and clearly designated to maintain order. Delays risk conflict. Thus, funerals became public events honoring the deceased, distributing tangible/intangible wealth to heirs—guided by tradition, tribal decision-makers, and the deceased’s wishes.

As Marcel Mauss and other anthropologists noted, genuinely free gifts are rare in pre-modern cultures. Apparently free gifts usually entail recipient obligations. Before contract law, such implicit obligations—and group condemnation/punishment for refusing them—likely powered most delayed exchanges, still common in informal mutual support. Only inheritance and kin altruism qualify as widely practiced “gifts” by our modern definition (non-obligatory gifts).

Early Western traders and missionaries often viewed natives as undeveloped, calling their tribute systems “gifts” and trade “gift exchange,” likening them to Western children’s Christmas/birthday gift swaps rather than adult legal/tax obligations. This reflects bias and a fact: Westerners had written legal duties, while locals lacked documents. Thus, Westerners translated native terms for transaction systems, rights, and duties as “gift.” In 17th-century America, French colonists surrounded by larger Indian tribes often paid tribute. Calling these “gifts” saved face among Europeans—who saw tribute as unnecessary and cowardly.

Unfortunately, Mauss and modern anthropologists retained this term—implying uncivilized people are childlike, naively morally superior, immune to our cold-blooded economic transactions. Yet in the West, especially legal contexts, “gift” denotes obligation-free transfers. This should be remembered when encountering anthropological discussions of “gift exchange”—it refers not to everyday free/informal gifts, but complex systems of rights and duties in wealth transfer. The only prehistoric exchange resembling modern gifts—neither widely recognized obligation nor imposing duty on recipients—is parental/maternal care and inheritance. (An exception: inheriting a title imposes the position’s responsibilities and privileges.)

Some heirlooms may interrupt lineage transmission but can’t form closed collectible-transfer cycles. They gain value only if ultimately usable for other purposes—typically inter-clan marital exchanges, forming closed collectible cycles.

Marriage Exchange

An early, significant example of small closed-loop collectible networks involves humans’ higher parental investment (vs. primate relatives) and associated marriage systems.

Marriage—blending long-term mating/child-rearing, intertribal negotiation, and wealth transfer—is a human universal, possibly as ancient as Homo sapiens.

Parental investment is long-term, largely “one-shot”—no time for repeated choices. From a genetic fitness perspective, divorcing an adulterous spouse usually means wasted years. Loyalty and commitment to children are primarily guaranteed by in-laws (clans). Marriage is essentially a clan contract, typically involving such loyalty, commitment, and wealth transfer.

Men and women rarely contribute equally to marriage; this imbalance worsens when clans arrange marriages and elders have few eligible partners. Most commonly, females are deemed more valuable, so the groom’s clan pays the bride’s clan. Conversely, brides’ families paying grooms’ clans is rare—occurring mainly in monogamous, highly unequal societies (e.g., medieval Europe, India), ultimately driven by elite males’ disproportionate potential advantages. Since most records concern elites, dowries feature prominently in European traditions—misrepresenting their rarity in human cultures.

Inter-clan marriages can form closed collectible cycles. Effectively, if brides desire collectible exchange, two clans exchanging members create a closed loop. A collectible-richer family can secure better (in monogamy) or more (in polygamy) brides for sons. In a marriage-only cycle, primitive money replaces clans’ need for memory and trust, enabling renewable resource credit repayable long afterward.

Like inheritance, litigation, and tribute, marriage requires triple coincidence. Without transferable, durable value storage, the groom’s clan’s ability to satisfy the bride’s desires would likely disappoint (this ability heavily influences groom-bride value mismatch, alongside political/romantic match needs). One solution imposes long-term service obligations on the groom/family—seen in 15% of known cultures. In 67% of cases, the groom/family pays substantial wealth to the bride’s family. Sometimes, bride price uses perishable goods—plants gathered/killed animals slaughtered for the wedding. In pastoral/agricultural societies, livestock (durable wealth) typically pays bride price. Remaining portions—often the most valuable in non-livestock cultures—are paid via prized heirlooms: rarest, most luxurious, durable necklaces, rings, etc. In the West, grooms give brides rings (suitors offer other jewelry)—once representing massive wealth transfers, common in many cultures. About 23% of cultures (mostly modern) involve no substantial wealth transfer. 6% involve mutual wealth exchange. Only 2% involve brides’ families providing dowries.

Unfortunately, some wealth transfers starkly contrast altruistic inheritance or noble marriage—like tribute.

Trophies

In chimpanzee troops and hunter-gatherer cultures (and analogs), violence-induced death rates far exceed modern civilization’s. This traces back to our common ancestor with chimps—troops constantly at odds.

Warfare includes killing, maiming, torture, kidnapping, rape, and extortion via threats of such fates. When adjacent tribes are at peace, one typically pays tribute to the other. Tribute can forge alliances, achieving economies of scale in war. Mostly, it’s exploitation—benefiting victors more than further violence would.

Post-victory, immediate value transfer from vanquished to victor typically follows—often as victors looting and losers hiding. More commonly, losers pay periodic tribute. Again, triple coincidence arises. Sometimes, complex adjustments reconcile losers’ supply capacity with victors’ needs. Yet primitive money offers a superior method—a universally accepted value medium greatly simplifying payment terms, crucial in eras lacking record-keeping or reliable memory. In some cases, like Iroquois Confederacy wampum, collectibles serve as primitive records—less precise than writing but aiding memory of terms. For victors, collectibles approach the Laffer-optimal tax rate in tribute collection (translator’s note: Laffer, famed for advocating tax cuts, theorized that up to a point, higher tax rates increase revenue, but beyond that, revenue declines as people avoid work). For losers, concealable collectibles enable “underreporting wealth,” convincing victors they’re poorer, thus reducing tribute. Hidden collectibles provide insurance against rapacious plunderers. Due to this concealability, much primitive society wealth escaped missionaries’ and anthropologists’ notice—only archaeologists uncover such hidden wealth.

Concealing collectibles and other tactics pose the same dilemma modern tax collectors face: estimating extractable wealth. While value measurement plagues many transaction types, none is more challenging than hostile taxation and tribute. After difficult, non-intuitive trade-offs and rounds of visits, audits, and collections, tribute maximizes revenue—even if costly for payers.

Suppose a tribe levies tribute on several defeated neighbors. It must estimate extractable value from each. Poor estimation lets some hide wealth while overburdening others, causing weakened tribes to shrink and advantaged ones to pay relatively less. In all cases, victors could gain more via better rules. This illustrates the Laffer curve’s guidance for tribal wealth.

Economist Arthur Laffer proposed the Laffer curve analyzing tax revenue: as tax rates rise, revenue increases but at a diminishing rate due to rising tax evasion and, crucially, reduced incentive to engage in taxed activities. Thus, a rate maximizes revenue. Raising rates beyond this Laffer optimum decreases government income. Ironically, the Laffer curve often advocates low taxes, though it’s a theory of maximizing government revenue, not social welfare or personal satisfaction.

At macro scales, the Laffer curve may be history’s most important economic principle. Charles Adams uses it to explain dynastic rise and fall. Successful governments, guided by self-interest, maximize income via the Laffer curve—balancing short-term gains and long-term success over rivals. Oppressive regimes like the Soviet Union and late Roman Empire collapsed; under-taxed governments often conquered by better-financed neighbors. Historically, democratic governments maintained high tax revenues peacefully, without foreign wars—the first states so rich relative to enemies they could spend heavily on non-military domains. Their tax systems approached the Laffer optimum more closely than most prior governments. (Alternatively, this spending freedom arose from nuclear deterrence, not democracies’ increasing revenue-maximization drive.)

Applying the Laffer curve to tribute agreements’ relative impacts, we conclude that revenue-maximization motives drive victors to accurately calculate conquered tribes’ income and wealth. Valuation methods critically determine how payers evade burdens via hiding wealth, fighting, or fleeing. Tribute collection becomes a game of misaligned incentives centered on value estimation.

With collectibles, victors can demand tribute at strategically optimal times, unconstrained by payers’ supply schedules or victors’ consumption needs. With collectibles, victors freely choose when to consume wealth, not forced to consume immediately upon receipt.

By 700 BC, trade was widespread, yet money remained collectible—though made of precious metals, its core features (l

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News