Sam Altman: Next year, OpenAI will enter the era of AI systems

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Sam Altman: Next year, OpenAI will enter the era of AI systems

Enhancing "reasoning capability" remains the core goal of this large model manufacturer.

Written by: 21VC

Translated by: Mu Mu

Edited by: Wendao

What big moves is OpenAI planning after GPT-4? What is OpenAI's moat? Where lies the value of AI agents? With many long-time employees leaving, will OpenAI shift toward younger, more passionate talent?

On November 4, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman (referred to as "Altman" below) addressed these questions in an episode of "The Twenty Minute VC" podcast. He clearly stated that improving reasoning capabilities has always been central to OpenAI’s strategy.

When asked by podcast host and 21VC founder Harry Stebbings (referred to as "Stebbings" below) what opportunities remain for AI entrepreneurs, Altman emphasized that building a business around fixing model shortcomings would quickly become uncompetitive as OpenAI’s models improve. Instead, founders should focus on creating businesses that benefit from increasingly powerful models—an enormous opportunity.

In Altman’s view, current discussions about AI are somewhat outdated. Compared to standalone models, systems represent the more promising frontier—and next year will be pivotal for OpenAI’s transition into advanced AI systems.

Below is an edited highlights transcript of the conversation between Stebbings and Altman:

OpenAI Plans to Build No-Code Tools

Stebbings: Let me start with a question from our audience—will OpenAI focus on releasing more models like GPT-3.5, or on training larger and stronger ones?

Altman: We’re committed to comprehensive model optimization, and enhancing reasoning ability is at the core of our current strategy. Powerful reasoning will unlock a range of transformative capabilities—such as enabling AI to make meaningful contributions to scientific research or write highly complex code—greatly accelerating societal progress. You can expect continuous and rapid iteration of the GPT series; this remains our top priority.

Sam Altman interviewed by Harry Stebbings, founder of 21VC

Stebbings: Will OpenAI develop no-code tools for non-technical users so they can easily build and scale AI applications?

Altman: Absolutely, we're steadily moving toward that goal. Our initial focus was significantly boosting programmer productivity, but our long-term vision is to deliver world-class no-code tools. While some no-code solutions exist today, none yet enable someone to create an entire startup purely through no-code means.

Stebbings: In which areas of the tech ecosystem does OpenAI plan to expand? Given OpenAI may dominate at the application layer, would it be wasteful for startups to invest heavily in optimizing existing systems? How should founders think about this?

Altman: Our mission is to continuously improve our models. If your business exists solely to patch minor limitations in current models, once those gaps disappear with better models, your business may lose its competitive edge.

However, if you build a business that benefits from ongoing model improvements, that presents a massive opportunity. Imagine knowing in advance that GPT-4 will become exceptionally capable—able to achieve things currently deemed impossible. That foresight allows you to plan and grow your business with a much longer time horizon.

Stebbings: We previously discussed with VC Brad Gerstner how OpenAI might impact certain niche markets. From a founder’s perspective, which companies do you think could be disrupted by OpenAI, and which could survive? As investors, how should we assess this risk?

Altman: AI will generate trillions of dollars in value, giving rise to entirely new products and services that make previously impractical or impossible tasks feasible. In some domains, we expect models to become so strong that achieving goals becomes trivial; in others, exceptional products and services built atop this technology will further amplify its impact.

In the early days, roughly 95% of startups seemed to bet that models wouldn’t get much better—I found that surprising then, though less so now. When GPT-3.5 launched, we already saw the potential of GPT-4 and knew it would be extremely powerful.

So, if your tool merely compensates for model weaknesses, those weaknesses will gradually vanish as models improve, making your solution increasingly irrelevant.

When models performed poorly, many preferred building products that patched flaws rather than revolutionary ones like an “AI teacher” or “AI medical advisor.” Back then, it felt like 95% were betting models wouldn’t improve, while only 5% believed they would.

Now the tide has turned. People understand the pace of improvement and our trajectory. This issue isn't as pressing anymore, but we were deeply concerned before because we foresaw that companies betting on static models might face serious challenges.

Stebbings: You’ve said “AI will create trillions of dollars in value.” Masayoshi Son (founder and CEO of SoftBank) predicts AI will generate $9 trillion annually—enough to offset what he sees as the necessary $9 trillion in capital expenditure. What’s your take?

Altman: I can’t give an exact figure, but clearly, massive investments will yield enormous returns—as with every major technological revolution, and AI is undoubtedly one of them.

Next year will be critical for us—we’re entering the era of next-generation AI systems. You mentioned developing no-code software agents. I’m not sure how long that will take—it’s not feasible today—but imagine achieving it: everyone could effortlessly access full enterprise-grade software suites. Think of the economic value unleashed. And if you maintain high output while making it easier and cheaper, the impact multiplies.

I believe we’ll see similar transformations in fields like healthcare and education—multi-trillion-dollar markets. If AI enables breakthroughs here, the exact numbers matter less than the fact that immense value will be created.

Top-Tier AI Agents Can Outperform Humans

Stebbings: What role do you see open-source playing in the future of AI? Internally at OpenAI, how do you debate whether certain models should be open-sourced?

Altman: Open-source models play a vital role in the AI ecosystem. There are already excellent open-source models available. I also believe offering high-quality services and APIs is crucial. To me, providing both as part of a product suite makes sense, allowing users to choose what best fits their needs.

Stebbings: Beyond open-source, we can serve customers via Agents. How do you define an 'Agent'? What is it—and isn’t it—to you?

Altman: An Agent, to me, is a program capable of performing extended tasks with minimal human oversight.

Stebbings: Do you think there are common misconceptions about Agents?

Altman: Less a misconception, more that we haven’t fully grasped the role Agents will play in the future.

A typical example people cite is using an AI Agent to book a restaurant—say, via OpenTable or even calling directly. That saves some time, but what excites me more is when Agents do things humans simply can’t—like contacting 300 restaurants simultaneously to find the perfect dish or special service. For humans, this is nearly impossible, but AI Agents can parallelize such tasks effortlessly.

This simple example shows how Agents can surpass human capability. More interestingly, an Agent could act like a brilliant senior colleague collaborating on a project—or independently complete a task that would take two days or even two weeks, only checking in when stuck, and delivering excellent results.

Stebbings: Could this Agent model affect SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) pricing? Traditionally, SaaS charges per user seat, but now Agents are replacing human labor. How do you see pricing evolving, especially as AI Agents become core team members?

Altman: It’s speculative—we don’t know for sure. But I can imagine a future where pricing is based on computing resources used—say, 1 GPU, 10 GPUs, or 100 GPUs to solve a problem. In that case, pricing shifts away from seats or even Agent counts, instead reflecting actual computational consumption.

Stebbings: Then, do we need specialized models built specifically for Agents?

Altman: Yes, significant infrastructure is needed to run Agents effectively, but GPT-3.5 already points the way—a general-purpose model capable of handling complex Agent tasks.

Models Are Depreciating Assets, But Training Experience Is Priceless

Stebbings: Many believe models are becoming commoditized and thus depreciating assets. Do you agree? With rising capital intensity in model training, does this mean only a few companies can afford it?

Altman: Yes, models can be seen as depreciating assets, but claiming their value is less than training cost is completely wrong. The real value lies in the compounding returns from training—knowledge and experience gained help us train future models more efficiently.

The revenue we derive from our models justifies these investments. Not all companies achieve this. Today, many train very similar models, but falling slightly behind—or lacking a product that consistently attracts users and delivers value—makes ROI harder.

We’re fortunate to have ChatGPT, used by hundreds of millions, so even with high costs, our vast user base helps absorb them.

Stebbings: How will OpenAI keep its models differentiated? Where do you most want to widen the gap?

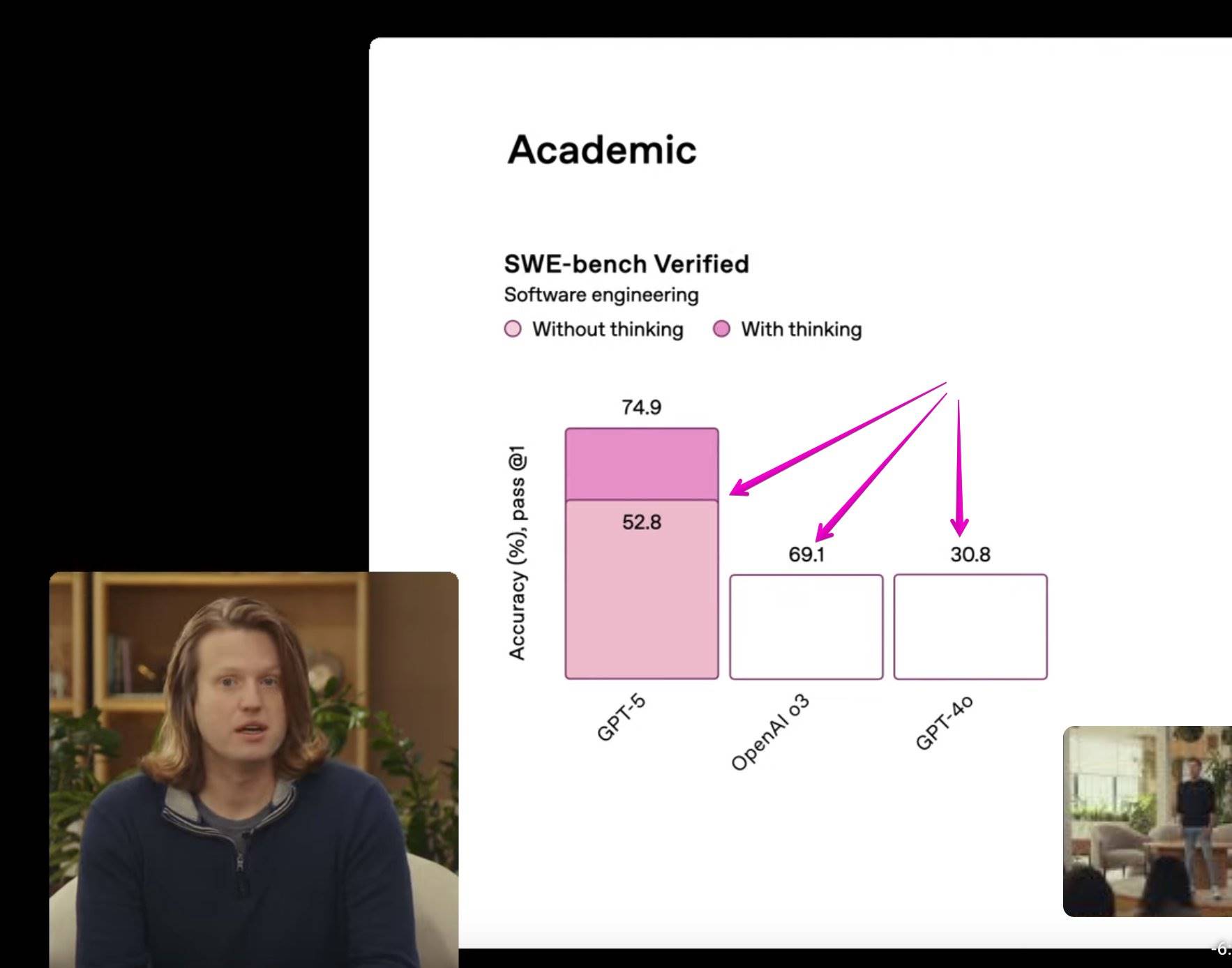

Altman: Reasoning capability is our top priority right now, and I believe it will unlock the next wave of large-scale value creation. Additionally, we’re investing in multimodal models and introducing new features we believe are essential for users.

Stebbings: Under the new GPT-3.5 reasoning-time paradigm, how will visual capabilities expand?

Altman: Without giving too much away, I expect image models to advance rapidly.

Stebbings: Anthropic’s models are sometimes seen as superior in programming tasks. What’s your view? Is that fair? How should developers choose between OpenAI and other providers?

Altman: Anthropic has a model that performs well in coding—their work is impressive. Developers often use multiple models, and I’m not sure how this will evolve. But I believe AI will eventually be everywhere.

The way we talk about AI today may already be outdated. I predict we’ll shift from discussing ‘models’ to discussing ‘systems’—though that transition will take time.

Stebbings: Regarding scaling laws, how long do you think they’ll hold? Many thought they’d fade quickly, yet they’ve lasted longer than expected.

Altman: Without diving into details, the key question is: will the trajectory of model capability improvements continue as it has? I believe it will—and for quite some time.

Stebbings: Have you ever doubted this?

Altman: We’ve encountered behaviors we couldn’t explain, faced failed training runs, experimented with new paradigms. When nearing the limits of a paradigm, we must find the next breakthrough.

Stebbings: What’s been the hardest challenge during this process?

Altman: During GPT-4 development, we hit extremely difficult problems that left us feeling stuck, unsure how to proceed. Eventually, we overcame them. But there was a period when we genuinely didn’t know how to move forward.

Also, the shift toward GPT-3.5-style reasoning models was something we dreamed of for years, but the research path was full of obstacles and detours.

Stebbings: How do you maintain team morale through such a long and winding journey? What happens when a training run fails?

Altman: Our team is deeply passionate about building AGI—an incredibly motivating mission. We all know it’s not easy, and success won’t come quickly. There’s a saying: “I never pray to be on God’s side—I pray to be on the side of God.”

Working in deep learning feels like pursuing a noble cause. Despite setbacks, we seem to always make progress eventually. That conviction is immensely helpful.

Stebbings: How concerned are you about semiconductor supply chains and geopolitical tensions?

Altman: I can’t quantify it, but yes, I am concerned. It’s not my top worry, but among all issues I care about, it’s firmly in the top 10%.

Stebbings: May I ask what your biggest concern is?

Altman: Overall, my greatest concern is the sheer complexity of everything we’re trying to accomplish across the field. I believe it will ultimately be resolved, but it’s an extraordinarily complex system.

This complexity exists at every level—within OpenAI and within each team. Take semiconductors: we must balance power supply, make correct networking decisions, secure enough chips, manage risks, and ensure research keeps pace—otherwise we’re caught off guard or waste resources.

The supply chain looks linear, but the ecosystem’s complexity at each level exceeds anything I’ve seen in other industries. In many ways, that’s precisely what worries me most.

Stebbings: You mentioned unprecedented complexity. Many compare today’s AI wave to the dot-com bubble, especially regarding excitement. I think the difference lies in funding scale. Larry Ellison (co-founder of Oracle) said entering the foundational model race requires a $100 billion entry fee. Do you agree?

Altman: No, I don’t think the cost will be that high. But there’s an interesting pattern: people love comparing new revolutions to past ones to make them feel familiar. Generally, that’s not helpful, though I understand why. I also think the analogies chosen for AI are particularly flawed—AI is fundamentally different from the internet.

You cited a cost example—whether it takes $10 billion or $100 billion to compete. A hallmark of the internet revolution was “easy entry.” Another similarity is that for many companies, AI is just an extension of the internet—others build the models, and you leverage them to create great products. That treats AI as a new way to build tech. But if you want to build AI itself, it’s a completely different game.

Another common analogy is electricity, but I think that doesn’t fit well either.

Though I caution against relying too much on analogies, my favorite is the transistor—a physics breakthrough with incredible scalability, quickly spreading across sectors. The entire tech industry benefited; our devices contain countless transistors, yet we don’t think of product creators as “transistor companies.”

It’s a complex, expensive industrial process with a massive supply chain. One physical discovery drove long-term economic growth—even when people weren’t aware of it, just thinking, “this thing helps me process information.”

Maintaining High Talent Standards, Not Age Bias

Stebbings: Where do you see human potential being wasted?

Altman: There are many talented people worldwide who can’t reach their full potential due to working at the wrong company, living in countries unsupportive of innovation, or other reasons.

One of the things I’m most excited about with AI is its potential to help everyone realize more of their abilities—a space where we currently fall far short. I believe there are countless latent AI researchers out there whose life paths took different turns.

Stebbings: You’ve experienced incredible growth over the past year. Looking back over the last decade, what’s changed most in your leadership approach?

Altman: The most unusual thing lately has been the speed of change. A typical company might take years to go from zero to $100 million in revenue, then to $1 billion, then $10 billion. We’re doing all that in just two years. Transitioning from a pure research lab to a company serving hundreds of millions has left little room for learning.

Stebbings: What areas do you wish you had more time to learn about?

Altman: How to push the company to aim for 10x growth, not just 10%. Growing from billions to tens of billions in revenue requires deep transformation—not just repeating last week’s work.

But rapid growth brings challenges—we lack time to solidify foundations. I underestimated how hard it is to keep up and keep moving forward in such an environment.

Internal communication, knowledge sharing, structured management, balancing short-term needs with long-term planning—all are critical. For example, ensuring execution readiness over the next 1–2 years requires提前 securing compute resources, office space, etc. Planning under such rapid growth is extremely challenging.

Stebbings: Keith Rabois (investor) once said he learned from Peter Thiel (PayPal co-founder) that hiring people under 30 is the secret to building great companies. What do you think of that advice—building companies around energetic, ambitious youth—is that the only way?

Altman: I was about 30 when I helped start OpenAI—not too young, but apparently young enough (laughs). So yes, it’s a viable path.

Stebbings: But youth brings energy and ambition, not necessarily experience. Should we prioritize proven experts instead?

Altman: Clearly, both approaches can succeed—as we’ve done at OpenAI. Just before this interview, I was discussing a young person who recently joined, probably early twenties, already doing exceptional work. I wonder if we can find more talents like him—they bring fresh perspectives and energy.

Yet, if you’re designing one of the most complex and expensive computing systems in human history, I wouldn’t casually hand that responsibility to a newcomer. So we need both. The key is maintaining high standards for talent, not favoring any age group.

I’m especially grateful to Y Combinator for teaching me that lack of experience doesn’t mean lack of value. Many early-career individuals have huge potential and can create immense value. Society should invest in them—that’s profoundly positive.

Stebbings: I recently heard a quote: “The heaviest burden in life isn’t iron or gold, but undecision.” Which unresolved decision weighs most on you?

Altman: The answer changes daily—no single decision stands out. Of course, we face big choices—product direction, next-gen computer design—important, risky calls.

Sometimes I delay decisions, but usually, the challenge is facing dozens of 51%-to-49% dilemmas daily. These land on my desk precisely because they’re hard. I’m not necessarily better equipped than others to decide, but I must decide.

So the pressure comes from volume, not any one specific decision.

Stebbings: When facing 51%-to-49% decisions, do you have go-to advisors?

Altman: No—I don’t think relying on one person for everything is wise. Better to consult 15 or 20 people with strong intuition and background in a given area, and pick the best expert depending on context, rather than depend on a single advisor.

Rapid-Fire Round

Stebbings: Suppose you were 23 or 24 today, with current infrastructure—what would you pursue?

Altman: I’d pick an AI-powered vertical—like AI education—and build the best AI education product to help people learn anything. Similar ideas: AI lawyer, AI CAD engineer, etc.

Stebbings: You mentioned writing a book—what would you title it?

Altman: I haven’t decided. I haven’t thought deeply about it—just that its existence might unlock a lot of human potential. Maybe something related to “human potential.”

Stebbings: In AI, what underappreciated direction deserves more attention?

Altman: I’d love to see an AI that understands your entire life. It doesn’t need infinite context, but some way to have an AI Agent that knows all your data and can assist you accordingly.

Stebbings: Anything surprise you in the past month?

Altman: A research result I can’t disclose—but it was stunning.

Stebbings: Who’s your most respected competitor? Why?

Altman: I respect everyone in the field—so many brilliant people doing outstanding work. I’m not dodging—I just see talent and excellence everywhere.

Stebbings: Any particular one?

Altman: No single standout.

Stebbings: Your favorite OpenAI API?

Altman: The new real-time API is fantastic. We now have a large API business with many great offerings.

Stebbings: Who in AI do you most admire today?

Altman: I’d highlight the Cursor team—they’ve created magical AI experiences and delivered real value. Many fail to piece everything together, but they succeeded. I intentionally didn’t mention OpenAI folks—otherwise the list would be too long.

Stebbings: Delay vs. accuracy—how do you balance them?

Altman: We need a dial to adjust between the two. Like now—you want quick answers, so I avoid spending minutes thinking. Here, latency matters. But if you want a major discovery, you might wait years. The answer is, it should be user-controllable.

Stebbings: Thinking about leadership insecurities, where do you most need to improve? As a leader and CEO, what skill do you most want to strengthen?

Altman: This past week, I feel less certain than before about the detailed contours of our product strategy. Overall, I see product as my weak spot, and the company now needs clearer product vision from me. We have a great product lead and team, but this is an area I wish I were better at—especially lately.

Stebbings: You hired Kevin Scott (OpenAI’s CTO), whom I’ve known for years—he’s excellent. What qualities make him a world-class product leader?

Altman: “Discipline” is the first word that comes to mind.

Stebbings: Specifically?

Altman: He’s intensely focused on priorities, knows what to say no to, thinks deeply from the user’s perspective about why to do or skip something—extremely rigorous, never flights of fancy.

Stebbings: Looking ahead five or ten years, if you had a magic wand to shape OpenAI’s vision, what would it look like?

Altman: I can easily picture the next two years. But if we get things right and start building extremely powerful systems—say, accelerating scientific progress—that could drive astonishing technological leaps.

I believe five years from now, we’ll see technological progress at a pace beyond anyone’s expectations—society might feel like “the AGI moment came and passed.” We’ll discover many new things, not just in AI research but across science.

At the same time, I think societal change will be relatively limited.

For example, five years ago, if you asked people whether computers would pass the Turing test, they’d likely say no. If you told them yes, they’d assume massive social upheaval. Now we’ve roughly passed it, yet society hasn’t changed dramatically.

That’s my expectation: technology continually surpasses expectations, while societal change lags. I think that’s good and healthy. Long-term, tech will transform society profoundly—but over five to ten years, the effects won’t manifest that quickly.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News