Wall Street's New Titan: Jane Street Rides the ETF Wave to Become the Most Profitable Trader

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Wall Street's New Titan: Jane Street Rides the ETF Wave to Become the Most Profitable Trader

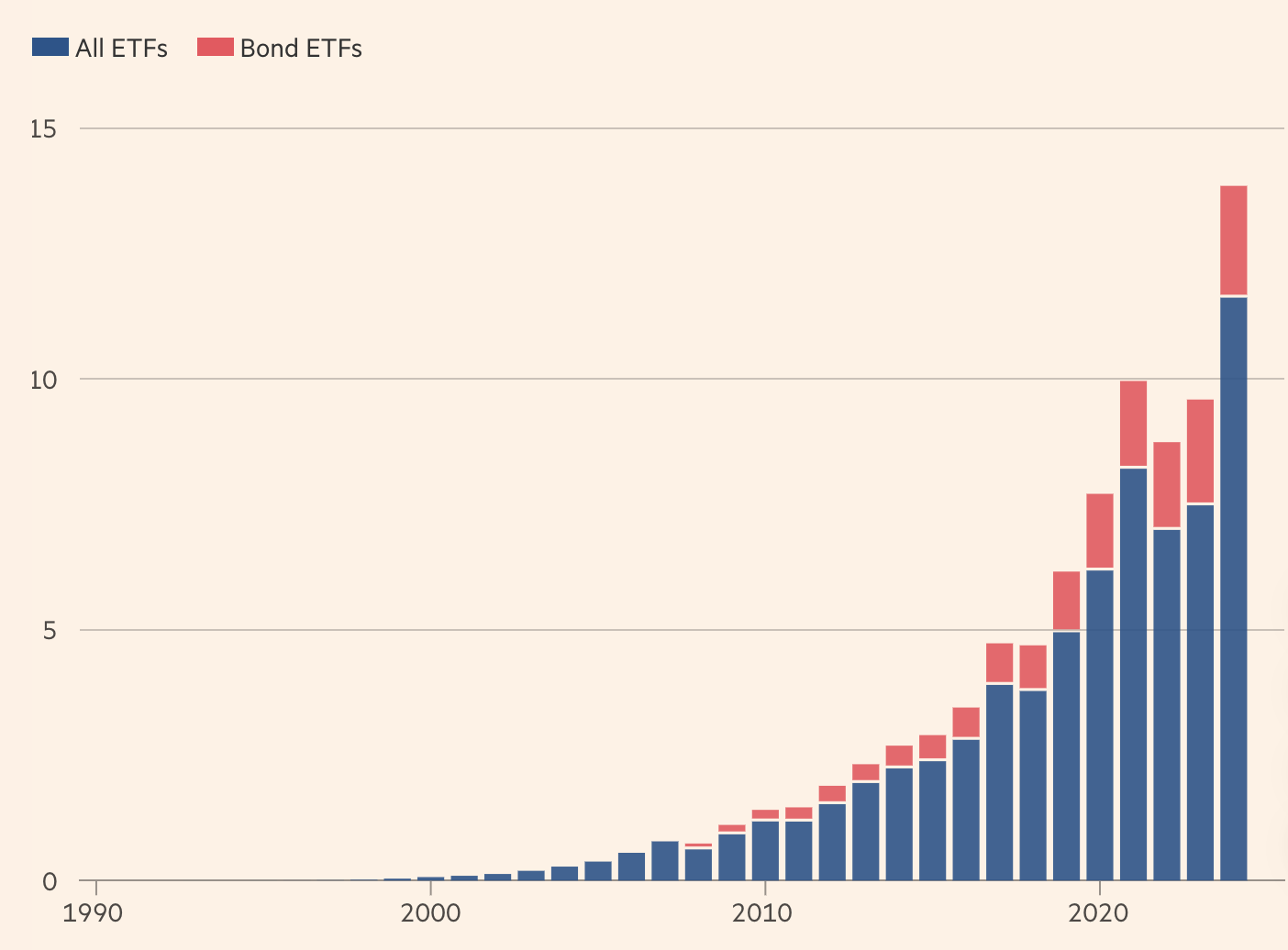

Last year, Jane Street accounted for 14% of U.S. ETF trading and 20% in Europe.

By Will Schmitt & Robin Wigglesworth

Translated by TechFlow

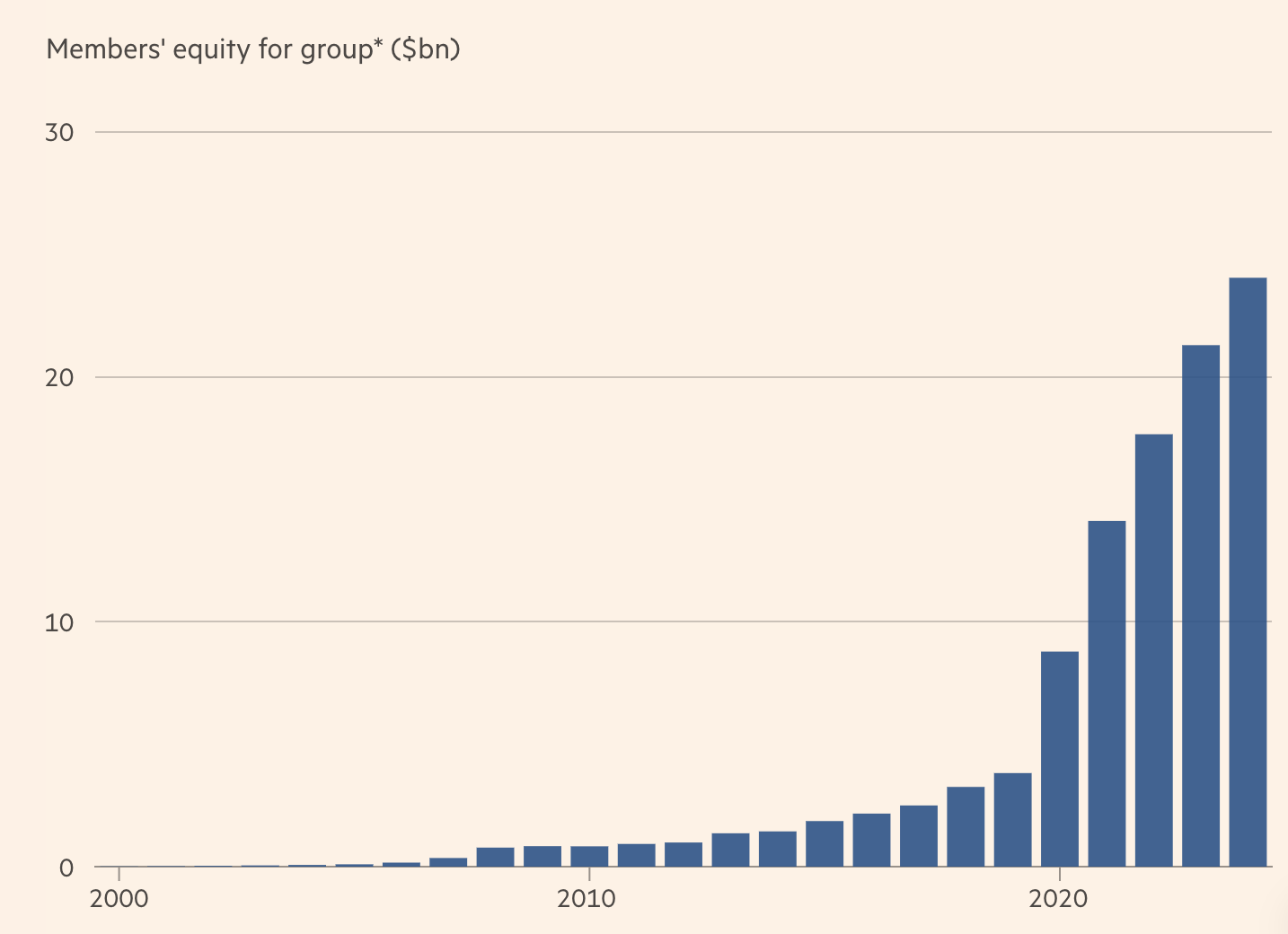

Jane Street generated more than $10 billion in net trading revenue for the fourth consecutive year last year, according to investor documents obtained by the Financial Times. Its total trading revenue of $21.9 billion equates to roughly one-seventh of the combined trading revenues from equities, bonds, currencies, and commodities at the world’s 12 largest investment banks last year, according to Coalition Greenwich.

"Their profitability is almost staggering," said Larry Tabb, a long-time industry analyst now at Bloomberg Intelligence. "It's because they handle many financial instruments others are unwilling to touch. That's where the highest profits lie—but also the greatest risks."

There are currently no signs that Jane Street’s growth is slowing. According to people familiar with the matter, its net trading revenue rose 78% year-on-year in the first half of 2024, reaching $8.4 billion. If it maintains this pace in the second half, Jane Street’s full-year trading revenue would surpass that of Goldman Sachs, a significantly larger firm, last year.

If it sustains the 70% profit margin disclosed in the documents, Jane Street’s annual income this year would comfortably exceed that of Blackstone or BlackRock, based on analyst forecasts compiled by LSEG.

Jane Street has particularly excelled in bond markets, rapidly entering a domain long dominated by banks and previously seen as inaccessible to independent trading firms.

"You can view Jane Street’s evolution as an ongoing process of automation—constantly tackling more complex tasks and then automating them," Matt Berger, head of fixed income at Jane Street, told the Financial Times. "That’s how our business continues to evolve."

Nonetheless, Jane Street faces numerous internal and external challenges.

Jane Street Has Ridden the ETF Wave

The once-low-profile trading firm has become one of the most watched players in finance—a spotlight that makes many Jane Street employees uncomfortable. Rapid growth is testing its traditionally flat, academic organizational structure. Competitors are poaching top talent. Some investors worry that Jane Street’s critical intermediary role in the fast-expanding bond ETF market could make it systemically important.

Meanwhile, rivals are fighting back: banks are trying to block its expansion in fixed income, while Citadel Securities is targeting Jane Street’s success in corporate bond markets.

"This is the classic innovator’s dilemma," said a former Jane Street employee. "When they were small, they moved fast and innovated in ways others couldn’t. Now that they’re a giant, of course others will catch up."

Jane Street was founded in 2000 by several traders from Susquehanna and a former IBM developer. For its first two decades, it quietly operated behind more established and well-known trading firms like Virtu Financial and Citadel Securities.

It began trading American depositary receipts—overseas company shares listed in the U.S.—in a small windowless office at the now-defunct American Stock Exchange. Soon after, it expanded into options and ETFs, the latter being championed years earlier by Amex.

ETFs were then a niche market; when Jane Street started trading them, total assets stood at around $70 billion. Yet ETFs quickly became a core business, and over time, Jane Street emerged as a key "authorized participant"—a market maker able to not only trade but also create and redeem ETF shares.

Jane Street particularly shines in less mainstream ETFs. Former and current executives say the firm’s love of puzzles—which features prominently in its rigorous interview process—reflects its willingness to tackle harder trading problems, such as handling ETFs in less liquid markets like corporate bonds, Chinese stocks, or exotic derivatives.

This means speed is less crucial at Jane Street than at high-frequency trading firms like Jump Trading, Citadel Securities, Virtu, or Hudson River Trading, despite often being categorized among them.

According to insiders and competitors, along the spectrum from intuitive traders at pre-2008 investment bank "proprietary desks" to fully technology-driven firms like Citadel Securities or Jump Trading, Jane Street sits closer to the middle. Positions are sometimes held for days or even weeks.

"It’s an interesting blend of technology and street smarts," said Gregory Peters, co-chief investment officer at PGIM Fixed Income.

Betting on ETFs proved wise, as the sector enjoyed a prolonged boom. ETF assets now approach $14 trillion, according to data provider ETGI. Jane Street gradually gained a reputation for attracting sharp talent seeking generous compensation—one reason young MIT graduate Sam Bankman-Fried joined in 2013.

Yet even within the industry, it is known for its distinctive use of OCaml, a programming language used to build nearly all its systems. To outsiders, it remains enigmatic—in keeping with which, Jane Street houses an original Enigma machine at its New York headquarters.

Its anonymity was so complete that three of its four co-founders quietly retired without public notice, leaving Rob Granieri, referred to internally as "first among equals." Jane Street has no CEO, and in loan documents shared with investors, describes itself as "a functional organization composed of various management and risk committees."

Each trading desk and business unit is overseen by one of 40 equity holders who collectively own $24 billion worth of Jane Street equity. While outsiders may see Granieri as a billionaire trading tycoon, employees describe him more as a low-key, long-haired figure akin to a Silicon Valley technologist. Major decisions, they say, are made collectively by a broader leadership group, a structure designed to promote collaboration and minimize hierarchy.

This is reflected in its compensation model—Jane Street does not tie pay to individual trading profits, or even to the performance of an employee’s specific desk. The firm has long avoided formal titles, even if this causes some confusion externally.

"Early on, when you gathered these people in a room, they wouldn’t hand out business cards, they’d all be in shorts and T-shirts—you had no idea who you were talking to," recalled Tabb of Bloomberg.

However, Jane Street’s low profile began to shift in 2020, when its massive profits during the turbulent pandemic markets made headlines.

Its earnings even surpassed those of Ken Griffin’s Citadel Securities, drawing widespread attention and sparking envy on Wall Street over reports of lavish pay. Marking its arrival on the biggest stage, in September 2020 the Federal Reserve added Jane Street to its list of eligible counterparties for crisis response measures, alongside stalwarts like JPMorgan.

Later, Jane Street drew further attention due to Sam Bankman-Fried launching his trading career there before founding the now-collapsed crypto exchange FTX. This publicity unsettled many at Jane Street, especially since Bankman-Fried’s risky and compliance-light approach led to prison time—something many insiders and outsiders view as starkly opposite to Jane Street’s extremely cautious culture.

Besides maintaining a central risk team of 14 people constantly monitoring all volatility exposures, Jane Street keeps an additional "liquidity buffer" equal to about 15% of its trading capital.

This reserve, held outside its main brokerage accounts, ensures Jane Street can maintain positions even amid market chaos. The firm also extensively uses derivatives to hedge against both small idiosyncratic shocks affecting individual desks and broad financial crises threatening the entire company.

Earlier this year, Jane Street returned to the spotlight by suing two former traders who defected in February to hedge fund Millennium Management. In court filings, Jane Street alleged that due to the deterioration of an Indian options strategy the traders reportedly took with them, the firm lost over $10 million per day. Since then, the two firms have been locked in legal battles over document disclosure.

Still, this scrutiny hasn’t slowed Jane Street’s momentum. Its rapidly growing trading revenues reflect expanding influence in equities and options markets. According to Berger, the firm plans to further expand into government bonds and currency trading over the next year, significantly scaling up its machine learning initiatives in terms of personnel, infrastructure, and computational capacity.

Jane Street’s Profit Growth Is Elevating Its Value

Yet, Jane Street’s core business remains ETFs. According to documents shared with lenders, Jane Street accounted for 14% of U.S. ETF trading and 20% in Europe last year. In bond ETFs, the firm estimates it handled 41% of all creation and redemption trades.

This market dominance enables Jane Street to enter the underlying bond markets—traditionally the preserve of banks—a key differentiator from its peers.

"Technologically advanced firms capable of real-time pricing and rapid response will earn higher profits," said Alexander Morris, chief investment officer at F/m Investments, which uses Jane Street as a market maker for its bond ETFs. "Because they’re faster and offer fairer prices, their goal is to execute quickly and move on—not to extract extra profit by delaying execution."

But after years of bumper returns, Jane Street appears to face mounting pressure.

Many banks have heavily invested in technology and restructured their trading operations to compete with firms like Jane Street, in both equities and bonds. These efforts are beginning to pay off. "They’ve closed many gaps," said Adam Gould, global head of equities at Tradeweb.

Meanwhile, Citadel Securities—already a major player in government bond markets—is now moving into corporate debt. "Competition has indeed intensified, and I think that benefits the overall market environment and investors," Berger said.

Yet Jane Street’s biggest challenge may come from within. Maintaining a collaborative, non-hierarchical culture was easier when all employees could fit on one floor in New York. But by the end of last year, the firm employed 2,631 full-time staff, nearly half spread across offices from Singapore to Amsterdam.

This is partly why the Millennium poaching incident raised concerns. As the firm grows larger and potentially less cohesive, it risks losing more employees and facing greater exposure to strategy leaks—an issue for a company that has consistently delivered strong performance.

"Even in bad years, Jane Street still paid generously—when it only had 100 to 200 people," said a former employee. "Now, it needs to support nearly 3,000."

If Jane Street has a weak year, the impact would be significant. A merely average performance would place the company in serious difficulty, putting it in a precarious position.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News