Can the ve token model prevent governance attacks suffered by Compound?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Can the ve token model prevent governance attacks suffered by Compound?

The governance mechanism of 1 token = 1 voting right has significant flaws, while the ve model has been battle-tested.

Author: Alex Liu, Foresight News

Governance Attack

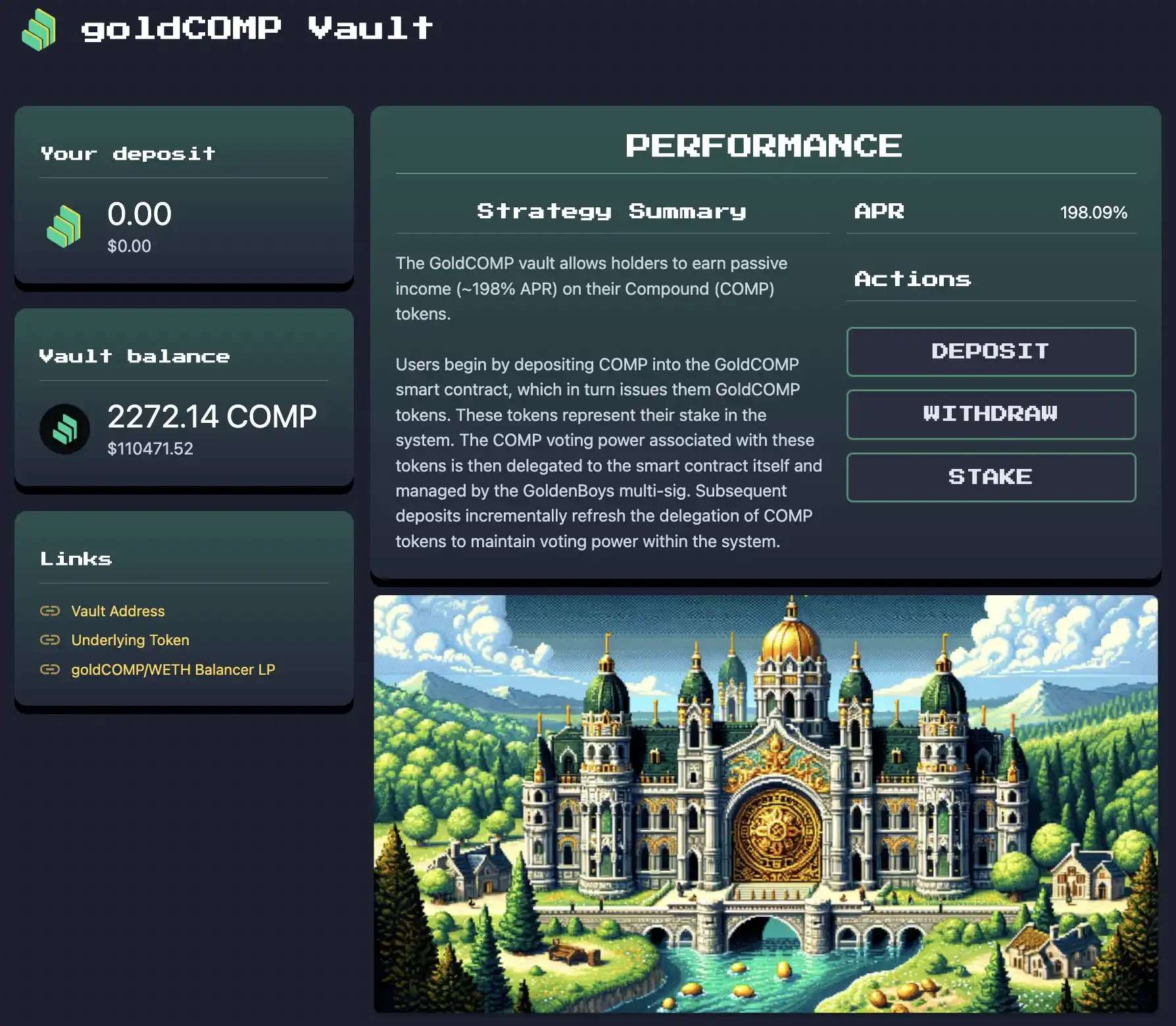

On July 29, the lending protocol Compound narrowly passed Proposal #289 by a vote of 682,191 to 633,636—allocating 5% of the protocol's reserve funds (approximately $24 million worth of 499,000 COMP tokens) to the "Golden Boys" yield protocol for one year.

Golden Boys yield pool

Community members accused stakeholders behind "Golden Boys" of orchestrating the proposal’s passage. Michael Lewellen, security advisor at Compound Finance, stated that several accounts accumulated large amounts of tokens on the open market, forcibly flipping the outcome in the final stage. Following the success of this maneuver, tokens related to "Golden Boys" surged sharply in value.

However, the proposal offered no benefit to the Compound protocol and instead caused it to lose control over part of its reserve assets, making this widely regarded as a “governance attack.”

How did this governance attack happen? And why might the ve token model reduce the likelihood of such incidents?

The Flaw in “1 Token = 1 Vote”

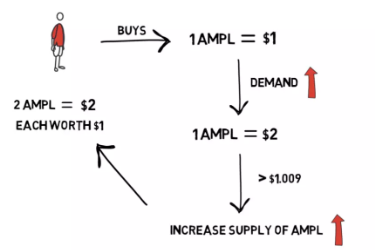

The flaw in governance models like Compound’s “1 token = 1 vote” system is quite apparent. If the private gain obtainable through passing a governance proposal exceeds the short-term holding cost of acquiring enough tokens to sway the vote, governance attacks become feasible.

For example: suppose seizing $5 million worth of tokens from a project’s treasury requires voting power equivalent to $30 million in governance tokens, and the governance process takes about two weeks. The attacker could buy $30 million worth of governance tokens on the market, hedge with an equal short position, and then sell the tokens and close the short after the vote concludes. This entire operation might cost only around $500,000.

The ve Solution

"ve" stands for vote-escrow, meaning “vote locking.” Simply holding a ve-model token like CRV grants no voting rights. To give 1 CRV full voting power, it must be locked for four years to receive 1 veCRV; locking for two years yields only 0.5 veCRV.

Attackers are unlikely to commit tokens for four-year lockups, which dramatically increases the cost of launching a governance attack. This mitigates the vulnerability in the “1 token = 1 vote” model, ensuring that only long-term holders deeply aligned with the protocol’s interests can participate in governance.

Moreover, because ve token holders influence protocol token emissions and earn rewards through voting and other governance activities, participation rates tend to be higher than in projects without the ve model.

Time Weighting

In cases like the governance attack on Compound, proposals suddenly reach the minimum required votes at the last moment. Governance mechanisms allowing such sudden reversals at the eleventh hour are immature and unfair—those who could still change the outcome may not have time to react, effectively losing their right to vote.

Protocols like Curve implement a vote decay mechanism, where votes cast in the final minutes carry little or no weight, specifically addressing the issue of last-minute result flips with no time for response.

Ultimately, the controversial Compound proposal was canceled via mutual agreement between parties, leading to a new proposal to distribute 30% of reserve earnings to stakers. The “1 token = 1 vote” governance model has significant flaws, while the ve model has proven resilient through real-world testing. To prevent similar events in the future, perhaps veCOMP is just around the corner?

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News