OpenAI CTO teases AGI keywords: will emerge within a decade, extremely advanced, intelligent system

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

OpenAI CTO teases AGI keywords: will emerge within a decade, extremely advanced, intelligent system

Senior journalist sharply questions OpenAI on training data sources.

Translation: Mu Mu

Editor: Wen Dao

In early July, at Johns Hopkins University, veteran tech journalist and co-host of the podcast Pivot, Kara Swisher, engaged in a heated dialogue with OpenAI CTO Mira Murati. Computer scientist and Stanford University professor Fei-Fei Li also joined the questioning—she is also the former Chief Scientist of AI and Machine Learning at Google Cloud.

Mira Murati rose to prominence during last year’s OpenAI “boardroom drama,” briefly serving as interim CEO after Sam Altman was ousted. In fact, this OpenAI CTO was a core member of the team that developed GPT-3 and played a key role in opening ChatGPT to the public.

During the conversation, Kara Swisher fired off sharp questions one after another—ranging from “Where does OpenAI source its training data?” and “Is Sora riskier than chatbots?” to allegations that OpenAI uses NDAs to silence employees and Scarlett Johansson's accusation of voice cloning—all directed squarely at Mira Murati. She even bluntly asked about Murati’s opinion of Sam Altman and their current relationship.

To every pointed question, Mira Murati “cleverly” avoided direct answers. Even as the journalist rephrased and pressed repeatedly, she maintained her own rhythm, often speaking in general terms and delivering OpenAI’s official messaging.

Privacy, misinformation, and value alignment—these are the AI risks people continue to worry about, and they were recurring themes throughout the discussion.

In Murati’s view, these concerns stem largely from public misunderstanding of AI technology. To overcome this, AI companies must not only strengthen safety measures to earn trust but also enable deeper public engagement with large models and applications—so people can understand both the potential and limitations of the technology. This shared participation creates a joint responsibility between users and developers to ensure AI evolves in a way that benefits human safety.

Kara Swisher repeatedly pressed for details on OpenAI’s timeline toward AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), but Murati remained tight-lipped, refusing to disclose any specific schedule. Still, she said, “Over the next decade, we will have incredibly advanced intelligent systems”—and not “the kind of traditional intelligent systems we already have.”

The full conversation was published on Johns Hopkins University’s official YouTube channel. Below are selected highlights:

On Collaboration with Apple

“OpenAI Does Not Store Apple User Data”

Swisher: Apple devices—computers, phones, and tablets—will begin integrating ChatGPT this year, which is a major event. It’s the first time Apple has done this, and they may partner with other companies in the future. I briefly spoke with Tim Cook (CEO of Apple) and heard his perspective. Now, I’d like to hear from you, Mira Murati: What is this partnership like from your standpoint?

Murati: This collaboration is an important milestone for us. Apple is an iconic consumer products company, and our goal has always been to bring artificial intelligence and excellent AI applications to as many people as possible. Working together offers a fantastic opportunity to deliver ChatGPT to all Apple device users without requiring them to switch between apps. Over the coming months, we’ll work closely with Apple to finalize product-level details, and more information will be shared soon.

Swisher: If you don’t mind, I’d like more specifics. What exactly are you doing? I discussed this with Tim Cook—he told me users could use ChatGPT to improve Siri, because right now, Siri is really bad.

But your current situation reminds me of Netscape—and clearly, you don’t want OpenAI to become the Netscape of AI. (Editor’s note: Netscape was one of the earliest and most important web browser startups in the 1990s. However, Microsoft challenged its dominance by bundling Internet Explorer with the Windows operating system, causing Netscape to gradually lose market share and eventually be acquired.) So, why did you strike a deal with Apple earlier than others?

Murati: I can speak about the product integration. We aim to bring our model capabilities—multimodality and interactivity—to Apple devices in a mature and seamless way.

You may have recently noticed the launch of GPT-4o. This marks the first significant leap in interactive dimensions for our models. It matters because up until now, our interaction with devices has been limited to text input. This opens up a much richer, more natural mode of communication, greatly reducing interaction constraints and unlocking many new possibilities—which is exactly what we’re pursuing.

Additionally, user requests sent to OpenAI are not stored, and IP addresses are anonymized—a critical point for Apple.

Swisher: Let’s dig into that: Can you still collect data from these requests to train your models?

Murati: No. We do not use user or customer data to train our models unless they explicitly allow us to do so.

Swisher: Apple places great importance on its reputation, especially regarding privacy and misinformation. They care deeply about where information goes and how it’s used.

Murati: We share those values, and this alignment helps move us in the direction we want. Privacy and trust are crucial to OpenAI’s mission because we must build and deploy technology in ways that make people feel trusted and empowered—that they have agency and a voice in how we build.

Regarding misinformation specifically, it’s very complex—misinformation has existed for decades. The internet and social media have amplified it in some ways. With AI, the problem becomes even more severe—AI is pushing these issues to a climax. But that’s actually good, because it brings attention to the problem and seems to be creating a collective sense of responsibility to take meaningful action.

I think this is an iterative process—we have to learn as we go. If you look back at the past 100 years of news and media governance, whenever new technologies emerged, systems adapted. Maybe that’s not the best analogy, but technological innovation helps us address misinformation before we tackle deeper societal readiness challenges.

Swisher: Speaking of Apple, you have to be extremely careful—make one mistake and they’ll come after you. I’m curious: How did this partnership start? Where did discussions between Tim Cook and Sam Altman begin? Or how did you get involved?

Murati: I don’t remember the exact timing, but it had been brewing for a while.

On Data Sources

Model Training Uses “Public, Collaborative, and Licensed” Data

Swisher: Are you discussing similar collaborations with other companies? Obviously, you have a partnership with Microsoft. Recently, OpenAI signed agreements with News Corp, The Atlantic, and Vox Media, authorizing the use of their content—avoiding at least three potential legal disputes.

I run my own podcast, but it wasn’t included in your deal with Vox Media. I might consider licensing it, though probably not—I don’t want anyone, including you, owning my content. So, how would you convince me to license my content?

Murati: When we use data to train models, we consider three main sources: publicly accessible data, publishers we partner with, and specific datasets labeled by paid annotators, as well as data from users who opt in. These are our primary data sources.

Regarding publisher partnerships, we place high value on accuracy and journalistic integrity because our users care about these too—they want reliable information and expect to see news reflected in ChatGPT. These partnerships are product-driven, aiming to deliver value through our applications.

We’re exploring different business models to compensate content creators when their data is used in products or model training. But these are one-on-one arrangements with specific publishers.

Swisher: You’ve reached agreements with some media outlets, but others chose to sue you—like The New York Times. Why did it come to that? I believe lawsuits are sometimes just a negotiation tactic.

Murati: That’s unfortunate, because we truly believe there’s value in incorporating news data and related content into our products. We tried to reach an agreement, but it didn’t work out.

Swisher: Yeah, maybe things will improve someday. But I think it’s because media companies have long dealt with internet firms and often ended up losing. Now, following our tradition, let’s invite the other guest to ask a question.

Li Fei-Fei: Data—especially big data—is considered one of the three pillars of modern AI intelligence. I’d like to ask a question on this topic. OpenAI’s success is heavily tied to data—we know OpenAI has collected massive amounts of data from the internet and other sources. So, what is your view on the relationship between data and models? Is it simply that more data equals better models? Or do we need to invest significant effort in curating diverse data types to ensure model efficiency? Finally, how do you balance the need for vast amounts of human-generated data with ownership and rights issues?

Murati: There are common misconceptions about AI models, especially large language models.

The developers don’t program models to perform specific tasks. Instead, they feed in vast amounts of data. These models ingest enormous datasets and function as powerful pattern-matching systems. Through this process, intelligence emerges. They learn to write, code, do basic math, summarize information, and much more.

We don’t fully understand how it works—but we know it’s highly effective. Deep learning is incredibly powerful. And this matters because people often ask how it works, which leads directly to transparency concerns.

Large language models combine neural network architecture, massive data, and immense computation to produce remarkable intelligence. This capability continues to grow as you add more data and compute.

Of course, we do extensive preprocessing to make data digestible. When thinking about transparency in model behavior and operations, we have tools available—because we want users to feel confident and empowered when using these models.

One thing we’ve done is publish a document called the model spec, which explains how model behavior works, the kinds of decisions we make internally at OpenAI, and those made jointly with human labelers. The spec defines current and desired model behaviors across platforms.

You’ll find complexity in the spec—sometimes conflicting goals. For example, we want the model to be helpful, but not break laws.

Say someone asks for “tips on shoplifting.” The model should refuse illegal requests. But sometimes, it might interpret the query as “how to prevent burglary” and give useful tips as a counterexample. This shows model behavior is complex—it can’t simply adopt one set of values. Ultimately, it depends on how people use it.

Swisher: But I think what confuses people is knowing what data is in the model and what isn’t. Data sourcing is a crucial piece. In March, when you were interviewed by The Wall Street Journal, you were asked whether OpenAI used video data from YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook to train Sora. You said you weren’t sure. But as CTO, shouldn’t you know what data was used?

Murati: I can’t disclose specific data sources—it’s a competitive trade secret. But I can say the data falls into three categories: 1) publicly available data; 2) data obtained via licenses and paid deals with content providers; 3) user-authorized data.

Swisher: Perplexity recently got into trouble for rapidly scraping online articles without clear attribution—any media company would be concerned about that.

Murati: Absolutely. We want to respect content creators and are exploring ways to compensate data originators. We’re developing a tool called the “content media manager” to help identify data types more precisely.

On Access

“Safeguards Must Be in Place Before Releasing Sora to the Public”

Swisher: When will Sora be released to the public?

Murati: We don’t have a public release timeline yet. Currently, we’ve given early access to select users and content creators to help us refine its features.

We’ve done extensive safety work and are studying how to roll it out in a way suitable for the public. It’s not simple—this is our standard process for launching any new technology. When we launched DALL-E, we first worked with creators to develop a more user-friendly interface. Essentially, we aim to expand human creativity.

Swisher: So is Sora potentially more dangerous than chatbots? Is this technology concerning—for instance, people easily generating deepfake porn with Scarlett Johansson’s face? Are you more worried about video?

Murati: Yes, video presents many challenges—especially when it’s done well. I think Sora performs exceptionally—it generates intuitive, emotionally expressive videos. Therefore, we must resolve all safety issues and implement safeguards to ensure the product is both useful and safe. From a business standpoint, no one wants a product that triggers safety or reputational crises.

Swisher: Yes, like Facebook Live (Editor’s note: Facebook Live is Facebook’s live-streaming feature, which faced issues with violent broadcasts in its early days, leading to regulatory scrutiny and negative publicity).

Murati: This amazing technology is truly incredible, but its impact and consequences are profound. So it’s vital that we get this right.

We follow an iterative deployment strategy—releasing to a small group first to identify edge cases. Only once we can handle them well do we expand access. But you need to define the product’s core and its business model, then iterate accordingly.

Swisher: I once covered a story on “early tech companies’ lack of concern for consequences”—they made us test subjects for early internet products. If they released a car this way, they’d be sued into bankruptcy.

Yet many technologies launch as beta versions and gain public acceptance. On the concept of consequences, as CTO, even if you can’t foresee everything, do you feel a responsibility to treat each invention with sufficient human respect and awareness of its potential impacts?

Murati: We assess consequences at both personal and societal levels—not just legal or regulatory, but moral correctness.

I’m optimistic. AI technology is astonishing—it will enable incredible achievements. I’m excited about its potential in science, discovery, education, and especially healthcare. But as with any powerful tool, there’s potential for catastrophic risks—and humans tend to amplify consequences.

Swisher: Indeed, I once quoted Paul Virilio in a book: “When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck.” But you corrected my overly anxious mindset.

Murati: I disagree with excessive pessimism. My background is engineering—engineering involves risk. Our entire civilization is built on engineering practice. Cities, bridges—they connect everything, but always carry risk. So we must manage these risks responsibly.

It’s not just the developer’s responsibility—it’s a shared one. To make shared responsibility real, we need to give people access and tools, inviting them to participate—not build technology in a vacuum, creating systems people can’t touch or influence.

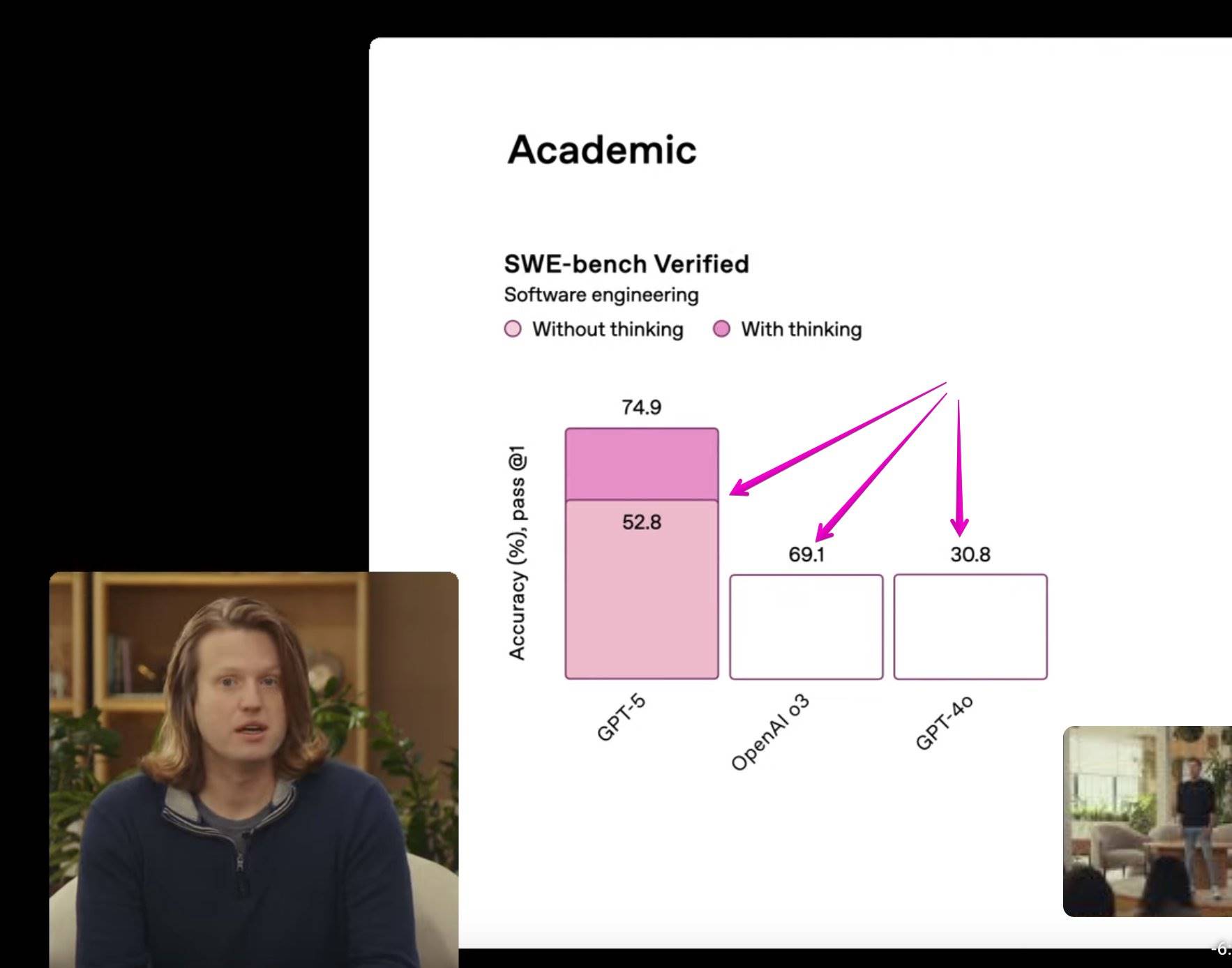

On GPT-5 and AGI

“The Next-Gen Model Will Be Extremely Powerful—Worth the Wait”

Swisher: You previously announced ChatGPT-4’s iteration—GPT-4o—and I love that name. You also announced you’re training a new model—GPT-5. Will it be exponentially better? When is it expected to launch?

Murati: O stands for Omni—“omnimodal”—meaning it integrates all modalities: vision, text, audio. What’s special is the seamless, natural interaction with the model. Its latency is nearly indistinguishable from face-to-face conversation—almost imperceptible. This is a huge leap in interacting with AI, very different from previous versions.

We want all users to experience the latest features for free, so everyone can see what the technology can do, what these new modalities look like, and also understand their limitations. As I said earlier, giving people access and involving them helps create intuitive understanding—making it easier to grasp both potential and limits.

Swisher: GPT-4o feels like an appetizer. What will the fifth generation offer? Is it incremental improvement or a giant leap?

Murati: We don’t know yet, but we’ll reveal it gradually… I don’t even know what we’ll call it. But the next-generation model will be extremely powerful—worth waiting for, like the leap from GPT-3 to GPT-4. Exactly how remains to be seen.

Swisher: You must have some idea about the next model’s features.

Murati: You’ll see when it comes.

Swisher: I’ll definitely know then—but what about you? What do you know now?

Murati: Even I don’t know.

Swisher: Really? Okay. You once mentioned OpenAI’s internal roadmap predicting AGI—Artificial General Intelligence—by 2027. That would be huge. Please explain why AGI matters and your estimate for when it’ll arrive.

Murati: People define AGI differently. Our definition is grounded in our charter: a system capable of performing economically valuable work across diverse domains.

Looking at our progress, the definition of intelligence keeps evolving. We used academic benchmarks; once achieved, we moved to school exams; eventually, saturated, we had to invent new tests. This makes you wonder: how do we assess adaptability and intelligence in real-world settings—interviews, internships, etc.?

So I expect the definitions of intelligence and AGI to keep evolving. Perhaps more importantly, we should focus on assessing and predicting its real-world impact—social and economic. What matters is how it affects society and how quickly it permeates.

Swisher: By that definition, when does OpenAI expect to achieve AGI? Is 2027 accurate?

Murati: I can only say that within the next decade, we will have extremely advanced intelligent systems.

Swisher: Intelligent systems? Are these “traditional” intelligent systems?

Murati: I think we already have traditional intelligent systems.

On Concerns About AI Safety

“Deep Engagement Is Key to Understanding Potential and Risks”

Swisher: OpenAI has people inside who want to benefit humanity, others chasing trillion-dollar valuations—or somewhere in between. I think you fall into that middle category.

Back in June last year, 13 current and former employees from OpenAI and Google DeepMind published an open letter calling on companies to grant them the right to warn about advanced AI risks. Employees from Meta, Google, and Microsoft also signed it.

Under these circumstances, some OpenAI employees said, ‘Broad NDAs prevent us from voicing concerns unless the company addresses these issues.’ To me, that basically means, “We can’t tell you the truth, or we’re dead.” Given fears of retaliation, how do you respond?

I won’t dive into equity issues since you’ve apologized and corrected them, but shouldn’t employees be able to express concerns? Shouldn’t dissent be allowed?

Murati: We believe debate is essential—publicly expressing concerns and discussing safety issues. We do this ourselves. Since OpenAI’s founding, we’ve openly voiced concerns about misinformation, even researching it during the GPT-2 era.

I think over the past few years, technological progress has been incredible and unpredictable, fueling widespread anxiety about society’s preparedness. As we advance, we see where science is leading us.

It’s understandable that people feel fear and anxiety about the future. I must emphasize: the work we do at OpenAI and how we deploy these models comes from an extraordinary team building and deploying the most powerful models in the safest possible way. I’m incredibly proud of that.

I also believe that, given the pace of technological advancement and our own progress, it’s critical to double down on discussing how we think about risks in training and deploying frontier models.

Swisher: Let me clarify. First, why do you need stricter confidentiality than other companies? Second, this open letter came after a series of high-profile departures, like Jan Leike and Ilya Sutskever, who led the Superalignment team focused on safety.

I wasn’t surprised by Ilya’s departure, but Leike posted on X saying OpenAI’s safety culture and processes from a year ago have been replaced by flashy products. That might be the harshest critique of you—and possibly a sign of internal division.

You stress that OpenAI takes safety seriously, but they say otherwise. How do you respond to such criticism?

Murati: First, the alignment team isn’t the only safety team at OpenAI—it’s a crucial one, but just one among several. Many people at OpenAI work on safety. I’ll elaborate shortly.

Jan Leike is an outstanding research colleague. I worked with him for three years and hold him in high regard. He left OpenAI to join Anthropic.

Given the pace of expected progress in our field, I believe everyone in the industry—including us—must redouble efforts in safety, security, preparedness, and regulatory engagement. But I disagree with the claim that we put product ahead of safety or prioritize it over safety.

Swisher: Why do you think they said that? These are people you worked with.

Murati: You’d have to ask them directly.

Many see safety as separate from capability—as if it’s a trade-off. I’m familiar with aerospace and automotive industries, where safety thinking is mature and systemic. In those fields, people don’t constantly debate safety in meetings—it’s assumed and deeply ingrained. I think the entire industry needs to evolve toward such mature safety disciplines.

We have safety systems and strict operational discipline—not just procedural, but covering today’s product and deployment safety, including harmful bias, misinformation, classifiers, etc.

We’re also working on long-term model alignment, using RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback), while addressing alignment challenges arising from increasingly powerful models.

Swisher: But OpenAI often faces accusations of prioritizing product over safety. I think it’s because you’re the leader now. But when someone leaves OpenAI and makes such claims, it carries more weight.

Even Sam Altman himself once told Congress, “AI could cause significant harm to the world,” and he signed a warning letter about extinction risks from AGI. That’s serious—and overlaps with what “AI doomers” say. Yet you keep launching AI products. So many say OpenAI just wants money and doesn’t care about harm.

Murati: I see that as overly cynical. OpenAI has an incredible team, all committed to our mission, working hard to develop and deploy systems safely. We were the first to deploy AI systems globally—via APIs—launching GPT-3, GPT-3.5, DALL-E3, and GPT-4. We’re extremely cautious to avoid worst-case scenarios.

Swisher: So we haven’t reached seatbelt-level safety standards yet. Car manufacturers once resisted installing seatbelts. Are we there yet, or will regulators force you to act?

The FTC launched an investigation into OpenAI in July, looking into unspecified consumer harms. Last week, they announced an antitrust probe into Microsoft’s deal with OpenAI. I thought Microsoft practically bought OpenAI but pretended not to. Technically, they own 49%. If forced to sever ties with Microsoft, how would that affect your competitiveness? What could you do if the government intervenes—on safety or anything else?

Murati: I think it’s good that people examine OpenAI. They should examine the whole industry.

We’re building an incredibly powerful tool and striving to make it exceptional—but it does carry risks. People should engage deeply, understand the nature of this technology, and explore its impacts across domains.

Understanding the tech alone isn’t enough. To deploy it safely and effectively, we need to build proper social and engineering infrastructure.

Therefore, I believe scrutiny is healthy—it encourages participation, independent validators, and more. We’ve discussed these issues earlier than anyone.

Regarding our specific collaboration with Microsoft, they’re a great partner. We’re working closely to build cutting-edge supercomputers. As you know, supercomputers are essential for training AI models. So this partnership is critically important to us.

On Executive Relationships

“I Push Back When Sam Pushes Too Hard”

Swisher: I’d like to talk about your role in the company and your relationship with Sam Altman. I like Sam—he’s wild and aggressive, like most technologists. Last year, he was fired and then reinstated. What happened? What was it like being interim CEO?

Murati: It was indeed quite stressful.

Swisher: Some board members said you had issues with his behavior. Your lawyer responded that you only gave him feedback. So, can you share your thoughts on him?

Murati: We’re just people running the company. We have disagreements and work through them. Ultimately, we’re deeply committed to our mission—that’s why we’re here. We put mission and team first.

Sam Altman is visionary, with bold ambitions, and has built an extraordinary company. We have a strong partnership. I’ve shared all my thoughts with the board when asked—there are no secrets.

Swisher: So how do you see your relationship now? You’re now one of the key figures in the company, and they’ve just hired others to strengthen management experience.

Murati: We have a very solid partnership—we can talk openly about any issue. The past few years have been tough; we’ve gone through growing pains, needing to keep the mission first, continuously improve, and maintain humility to grow.

Swisher: Partnerships evolve as companies grow. I know this well—from early days at Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. Google’s early phase was chaotic; Facebook cycled through many COOs—Zuckerberg replaced executives he didn’t like multiple times.

So how do you view your partnership? How do you interact with Sam daily? What do you push back on? He’s invested in 400 companies—some hoping to partner with OpenAI. He also invested $375 million in Helion, an energy firm now supplying massive power to OpenAI. Computing requires enormous electricity, after all.

Murati: When do I push back? All the time. I think it’s normal in how we operate. Sam pushes the team extremely hard—I think that’s good. Having big visions and testing our limits is fantastic. But when I feel it goes too far, I push back. That’s been our dynamic for six years. I think it’s effective—I can challenge him.

Swisher: Can you give an example? Like in the Scarlett Johansson incident—you were involved in that voice project, right?(Editor’s note: Scarlett Johansson accused OpenAI of using her voice without permission in ChatGPT-4o’s voice system, Sky.)

Murati: We have a good partnership, but choosing the voice wasn’t a priority for us nor a joint decision. I was involved in the decision—I picked Sky’s voice, then he reached out to Scarlett Johansson. Sam has his own network, and there was no coordination on this decision—it was unfortunate. He has his own connections, so this time we weren’t fully aligned.

Swisher: Do you consider this a major misstep by OpenAI? Because everyone says it looks like you “stole” Scarlett’s voice. Though that’s not true—you used a similar-sounding voice. But it reflects fears about tech companies taking creators’ resources.

Murati: Are you worried about tech companies being accused of taking everything from creators?

Swisher: Actually, I think that’s exactly what happens.

Murati: I am concerned about that perception. But all we can do is do our work well, on every project, so people see our effort and build trust. I don’t think there’s any magic formula for building trust beyond actually doing the work well.

Swisher: Have you spoken with Scarlett Johansson?

Murati: No. It happened very urgently. I was focused on work. Also, I grew up in Albania and the Balkans, so I wasn’t exposed to much American pop culture.

On Preventing AI-Generated Misinformation

“Metadata and Classifiers Are Two Technical Approaches”

Swisher: Let me end with elections and misinformation.

New research suggests online misinformation is less impactful than we thought—its effects are limited. One study found OpenAI addresses demand-side issues: if people want conspiracy theories, they’ll seek them on radio, social media, etc. Others argue misinformation is a huge problem.

You’ve heard prior discussions—many conspiracy theories, largely driven by social media. So, when you think about AI’s power to spread misinformation and its impact on upcoming presidential elections, what worries you? From your perspective, what’s the worst-case scenario and most likely negative outcome?

Murati: Current systems are highly persuasive and can influence your thinking and beliefs. This is something we’ve studied and confirmed—it’s a real issue. Especially over the past year, we’ve been deeply focused on how AI affects elections. We’re taking several actions.

First, we actively prevent misuse—including detecting political information accuracy, monitoring platforms, and acting swiftly. Second, we reduce political bias—you may have seen ChatGPT criticized as too liberal. That’s not intentional—we’re working hard to minimize political bias in model behavior and will continue. Third, we aim to guide voters to accurate voting information.

On misinformation, deepfakes are unacceptable. We need reliable methods for people to know when they’re viewing a deepfake. We’ve taken steps—implementing C2PA for images, like a digital passport that travels with content across platforms. We’ve also open-sourced DALL·E’s classifier to detect whether an image was generated by DALL·E.

So metadata and classifiers are two technical approaches—provenance for content, specifically images. We’re also researching watermarking for text. But the key is: people should know what’s a deepfake. We want people to feel confident in the information they see.

Swisher: The FCC just fined a company $6 million for creating a deepfake audio that sounded like Biden in the New Hampshire primary. More sophisticated versions may emerge.

OpenAI is developing a tool called Voice Enunciation that can clone someone’s voice from a 15-second clip, enabling synthesis in other languages. A product manager told The New York Times it’s a sensitive issue. Why are you building this? I often tell technologists: if what you’re building feels like a Black Mirror episode, maybe you shouldn’t build it.

Murati: I think that’s a hopeless attitude. This technology is amazing—with huge potential. We can do it responsibly. We should remain hopeful.

We developed Voice Enunciation in 2022 but didn’t release it. Even now, access is extremely limited, as we’re still working through safety issues. But you can’t solve these alone—you need experts across fields, civil society, governments, and creators. It’s not a one-time fix—it’s extremely complex, requiring massive effort.

Swisher: You answer this way because you’re optimistic. My next analogy may be exaggerated: if you’re a pessimist, some say if I don’t stop Sam Altman, he’ll destroy humanity; others say it’s the best thing ever, and we’ll all enjoy delicious Snickers on Mars.

It feels like today’s Republican-Democrat divide—two wildly different narratives. So can you tell me, what worries you most, and what do you most hope to achieve?

Murati: I don’t think the outcome is predetermined. We have institutions that can shape how this technology is built and deployed. To do it right, we need to create a sense of shared responsibility.

It hinges on understanding the technology. The real risk lies in misunderstanding it—many don’t grasp its capabilities or risks. That’s the biggest danger. In specific contexts, how our democracy interacts with these technologies is crucial.

We’ve discussed this many times today. The risk of “persuasion” is particularly alarming—strongly influencing people to act a certain way or controlling society’s direction. That’s terrifying.

On hopes: I’m excited about delivering high-quality, free education anywhere—even remote villages with no resources.

Education changed my life. Today, with electricity and internet, these tools are accessible. Sadly, most people still learn in classrooms—one teacher, 50 students, same material. Imagine if education could be tailored to your thinking style, culture, and interests. That would dramatically expand knowledge and creativity.

We usually start thinking about learning late—maybe in college or later. But if we could master AI early to learn how to learn, I believe it would be transformative—accelerating human knowledge and advancing civilization.

We have tremendous agency in how we build and deploy technology globally. But to ensure it develops correctly, we must foster shared responsibility. The key is comprehensive understanding and accessibility. Bias often stems from misunderstanding the technology’s essence—leading to both underestimating its potential and overlooking its risks. In my view, that is the greatest hazard.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News