The prevailing state of the venture capital market: intense competition, with returns concentrated in specific sectors.

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The prevailing state of the venture capital market: intense competition, with returns concentrated in specific sectors.

We are currently in a period of low liquidity, near the bottom of the market cycle.

Author: DEZ

Translation: TechFlow

What is the current state of the venture capital industry? If you ask a venture capitalist for their view on today’s market, you’ll likely hear three consistent statements:

A) The market is overcrowded

B) Competition is extremely fierce

C) Returns are concentrated at the top.

This is an interesting and consistent commentary, especially given the central role venture capitalists play in the startup ecosystem. So, is venture capital a dying asset class? Certainly not. But does it face structural challenges? Undoubtedly.

Let’s examine this from a macro perspective.

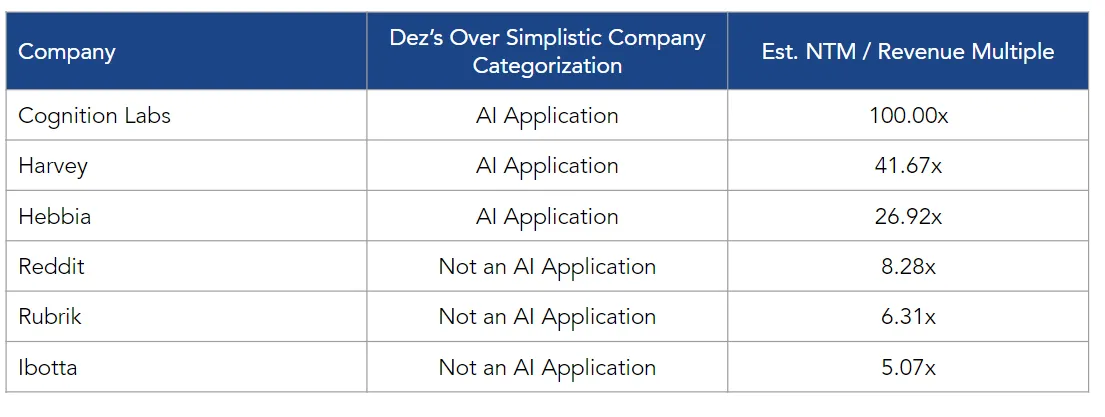

As of 2024, three notable venture-backed companies have gone public: Reddit, Rubrik, and Ibotta. As of earlier this week, these companies had enterprise values of approximately $10 billion, $6 billion, and $2 billion respectively, with projected revenues over the next twelve months of $1.2 billion, $922 million, and $415 million.

These are large, well-capitalized, and well-known businesses with user bases ranging from millions to hundreds of millions. They’ve crossed the so-called “chasm” and are now striving to become efficiently run public companies. These billion-dollar success stories are the dream of every venture capitalist and can dramatically elevate our careers.

Yet, despite the fact that returning capital is ultimately the only thing that matters to venture investors, we (as an industry) remain all too willing to suspend disbelief when it comes to the core of our work—pricing.

Over the past few weeks, the early-stage startup landscape has continued to bifurcate into two categories: AI-native companies and everyone else.

AI-native companies focus on applications, inference, and frontier/deep tech model layers. Companies like Hebbia recently raised funds at a $700 million valuation, Cognition Labs now has a $2 billion valuation (just six months later—an astonishing jump), and Harvey is reportedly closing a round at a $1.5 billion valuation.

In fact, we aren’t living in a world where such valuations are rare. They’re actually quite common. Other companies like Glean ($2 billion valuation), Skild AI ($1.5 billion valuation), and Applied Intuition ($6 billion valuation) further reinforce this trend. I happen to know Hebbia, Cognition, and Harvey particularly well, and they share several advantages:

-

They are generating revenue: Hebbia reportedly earns $13 million in revenue and is already profitable, Cognition likely generates between $5–10 million, and Harvey exceeds $20 million in revenue.

-

They are building brand and talent density: A look at their teams reveals many Ivy League graduates and seasoned technical experts.

-

They have blue-chip clients: Including PwC, KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.), T-Mobile, Bridgewater Associates, the U.S. Air Force, Centerview Partners, and others.

-

They represent a generational shift in software: Focusing more on outcomes than workflows (i.e., don’t help me do the work—just do the work for me).

However, despite questionable unicorn valuations, all remain firmly within the “chasm.” There is no guarantee any will survive to go public. Competition in this space is intense. The technology they’re building may plateau, failing to deliver clear ROI to end customers. Meanwhile, public company peers, which are 20x larger in revenue scale, have already established themselves as market leaders and trade at 5x to 8x forward revenue—not 20x to 100x.

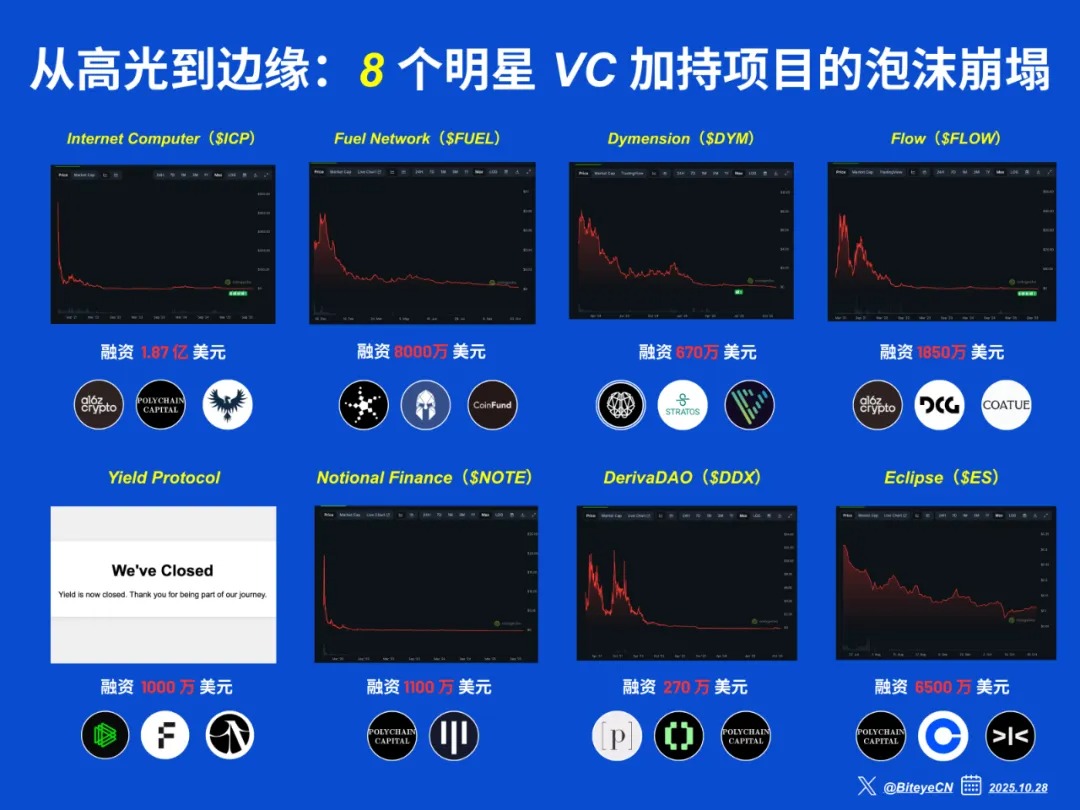

This is the structural challenge facing venture capital: excess capital chasing scarce high-quality assets, leading to unsustainable valuation inflation that ultimately erodes equity value. Yet among these frothy valuations, some will later appear relatively cheap. Today, truly durable, generational companies are indeed being built—but no one can clearly tell which ones will end up like Webvan and which will become Doordash.

(Translator’s note: It's difficult to predict which companies will ultimately fail and which will achieve massive success.)

Webvan: An online grocery delivery company founded in 1999 that went bankrupt in 2001 due to poor management and underestimated market demand. Webvan is often cited as a classic example of startup failure.

Doordash: An online food delivery platform founded in 2013 that rapidly expanded and successfully went public in 2020, becoming a multi-billion dollar market cap company. Doordash is a prime example of startup success.)

Companies like Doordash generate outsized returns for their investors, which in turn fuels renewed interest in venture capital as an asset class. This cycle repeats itself, and by 2040, we might be discussing a new investment technology experiencing similar pricing dislocations. This is the current state of venture capital. To clarify further, I believe several themes about its present condition are crystal clear:

-

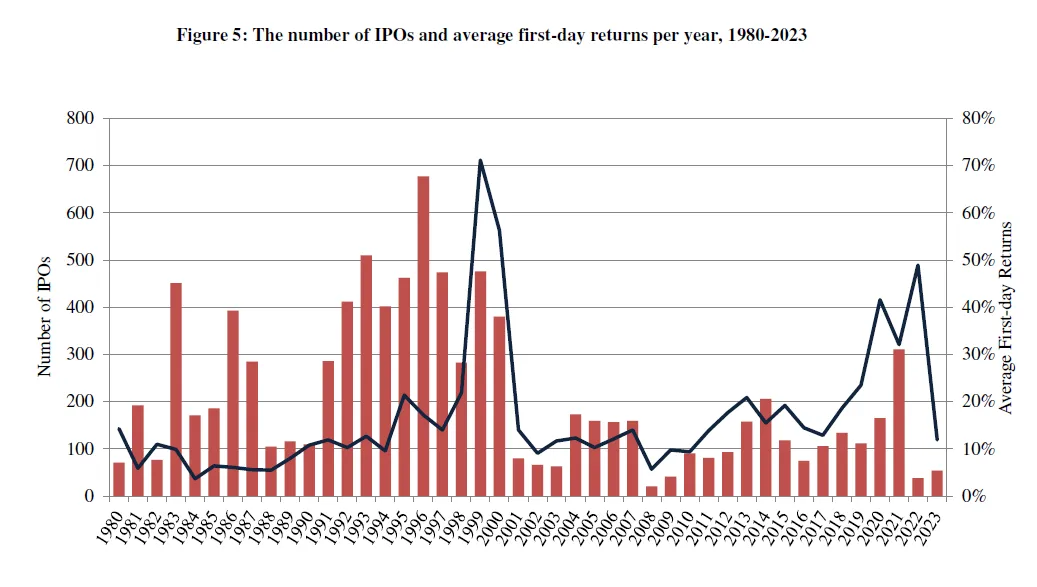

We are in a period of low liquidity, near the bottom of the market cycle. 2022 was the worst year for IPOs since the global financial crisis, and 2023 showed little improvement.

-

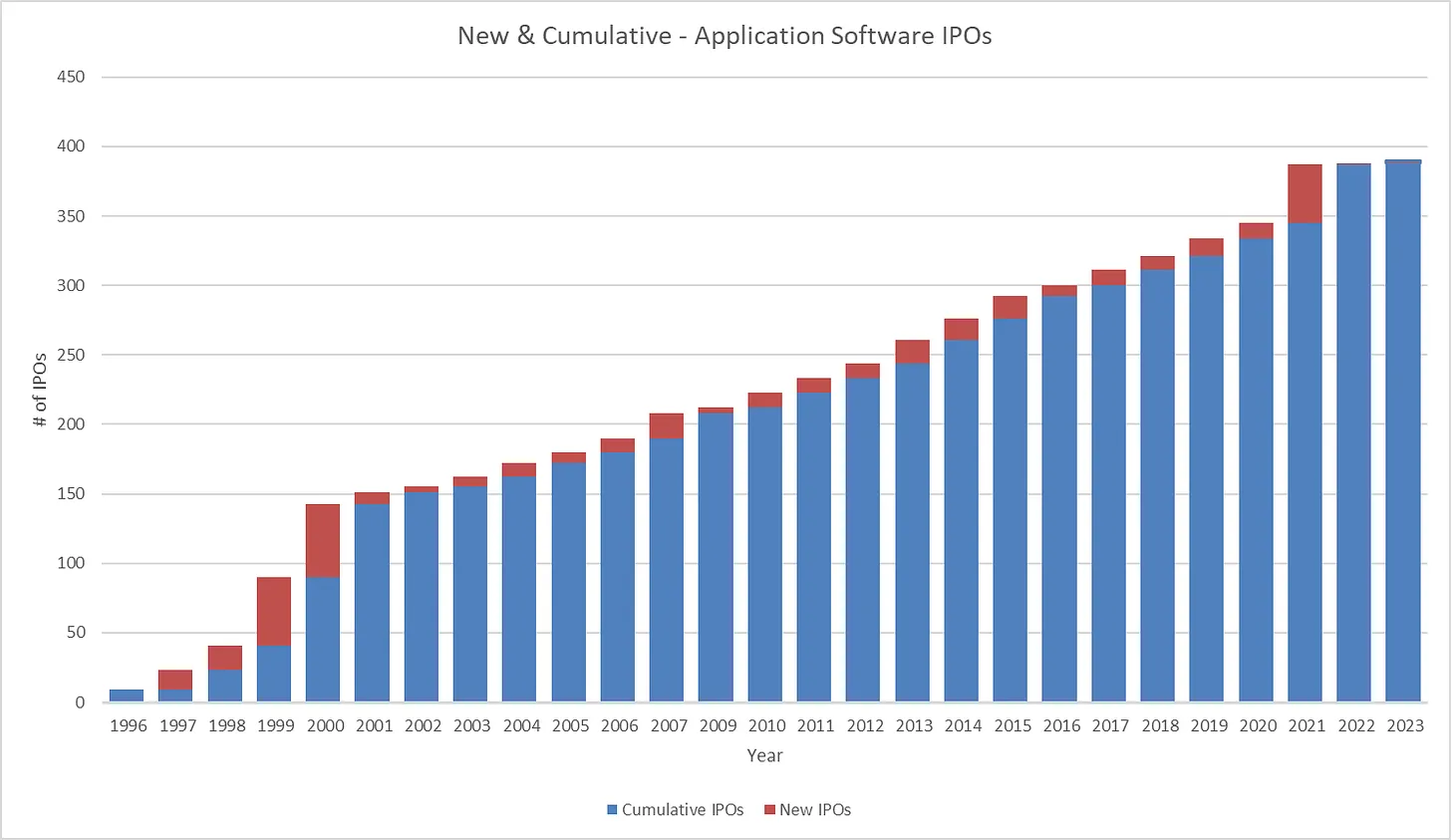

Application software has long been a gift that keeps giving, accounting for 8% of all IPOs since 1996, but it is maturing as a venture sub-sector. As a result, the addressable market opportunity is shrinking.

-

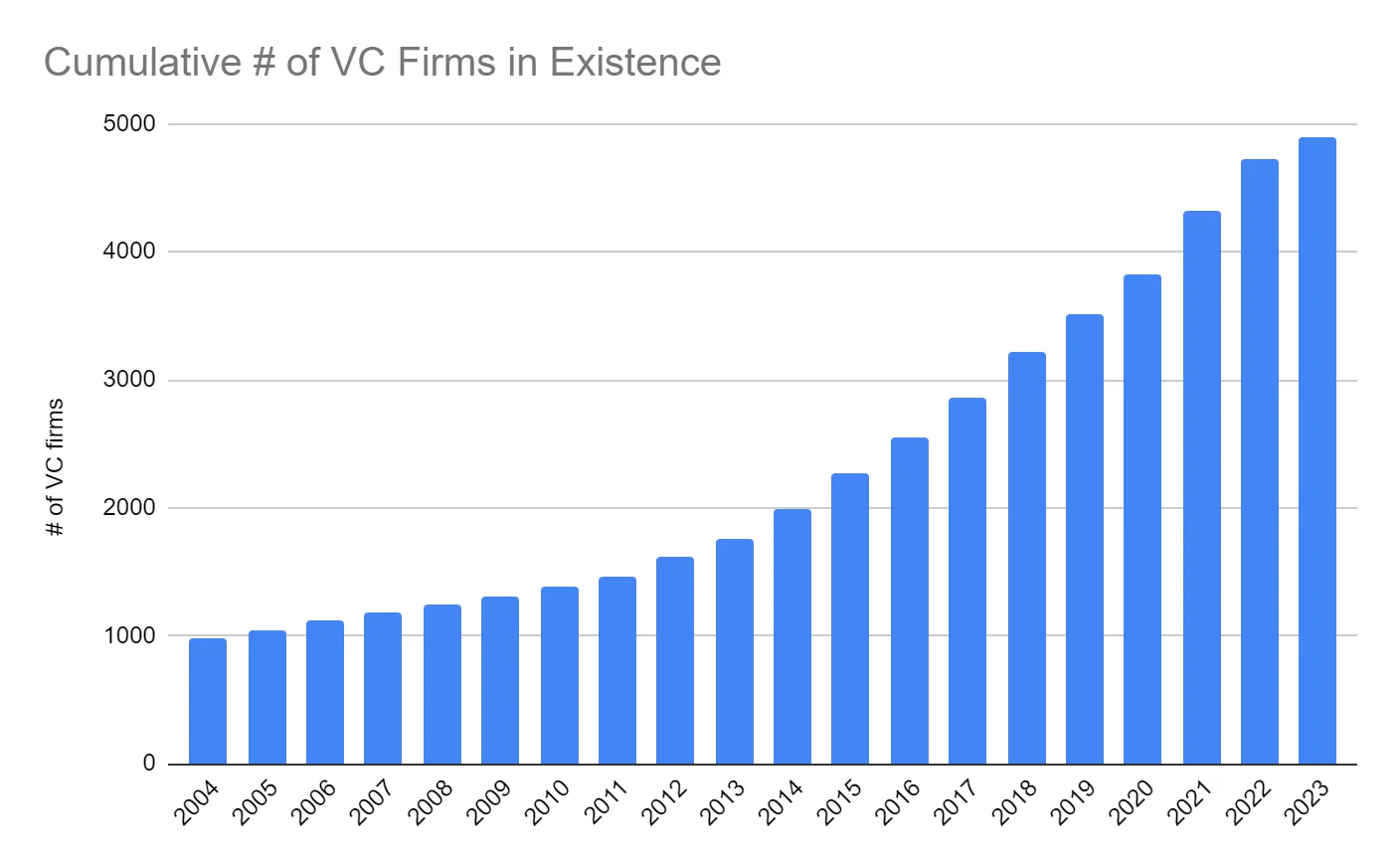

Venture capital has never been more competitive. Over the past 20 years, the venture asset class has grown more than fourfold. This embodies the principle: “Your margin is my opportunity.”

-

For assets deemed unique, price is no longer a consideration. Revenue multiples of 100x are accepted and increasingly common.

If I were to distill my core argument, it’s this: when you turn $7 million into $4 billion, it tends to attract competition—and competition is the defining feature of today’s venture landscape. Pricing, deal speed, intensity of the investment process—all stem from competition, which today is best illustrated by “two cities”: AI-native companies versus everyone else.

Now, the real question is, if this is the state of venture capital, so what? I have my own thoughts and strategies underway, but I’ll keep those to myself for now. In the meantime, wishing everyone a great week and good investing.

-

To avoid confusion, I did not speak directly with these companies. These figures are estimates drawn from public records and private conversations.

-

To clarify, I’m not saying these are prerequisites for success, but they are strong early indicators of talent clustering.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News