A Brief History of Asset Tokenization: A Rocky Road, A Bright Future

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Brief History of Asset Tokenization: A Rocky Road, A Bright Future

As more assets, applications, and users move on-chain, the platform itself and the blockchain will become more valuable, making them more attractive to builders, issuers, and users.

Author: ALEX WESELEY

Translation: TechFlow

Article Overview

In this article, author ALEX WESELEY explores the potential and challenges of tokenizing financial assets on public blockchains. Although tens of billions of dollars in real-world financial assets have already been tokenized and deployed on public blockchains, significant work remains at the intersection of law and technology to rebuild the infrastructure of the financial system on public blockchains. The article reviews the historical context of traditional financial markets—particularly the paperwork crisis of the 1960s—to reveal vulnerabilities and inefficiencies in existing systems. The author argues that public blockchains possess unique advantages in addressing these issues in a globally credible and neutral manner.

Key Points

-

Although tens of billions of dollars in real-world financial assets have already been tokenized and deployed on public blockchains, substantial work remains at the intersection of law and technology to reconstruct the financial system’s infrastructure on public blockchains.

-

History shows that the current financial system was not designed to support today’s levels of globalization and digitalization, having evolved into a closed system built upon outdated technologies. Public blockchains offer unique advantages in solving these problems in a globally credible and neutral way.

-

Despite the challenges, we at Artemis believe that stocks, government bonds, and other financial assets will migrate onto public blockchains because they are more efficient. This will unlock network effects as applications and users converge on a common foundational platform that enables programmable and interoperable assets.

Introduction

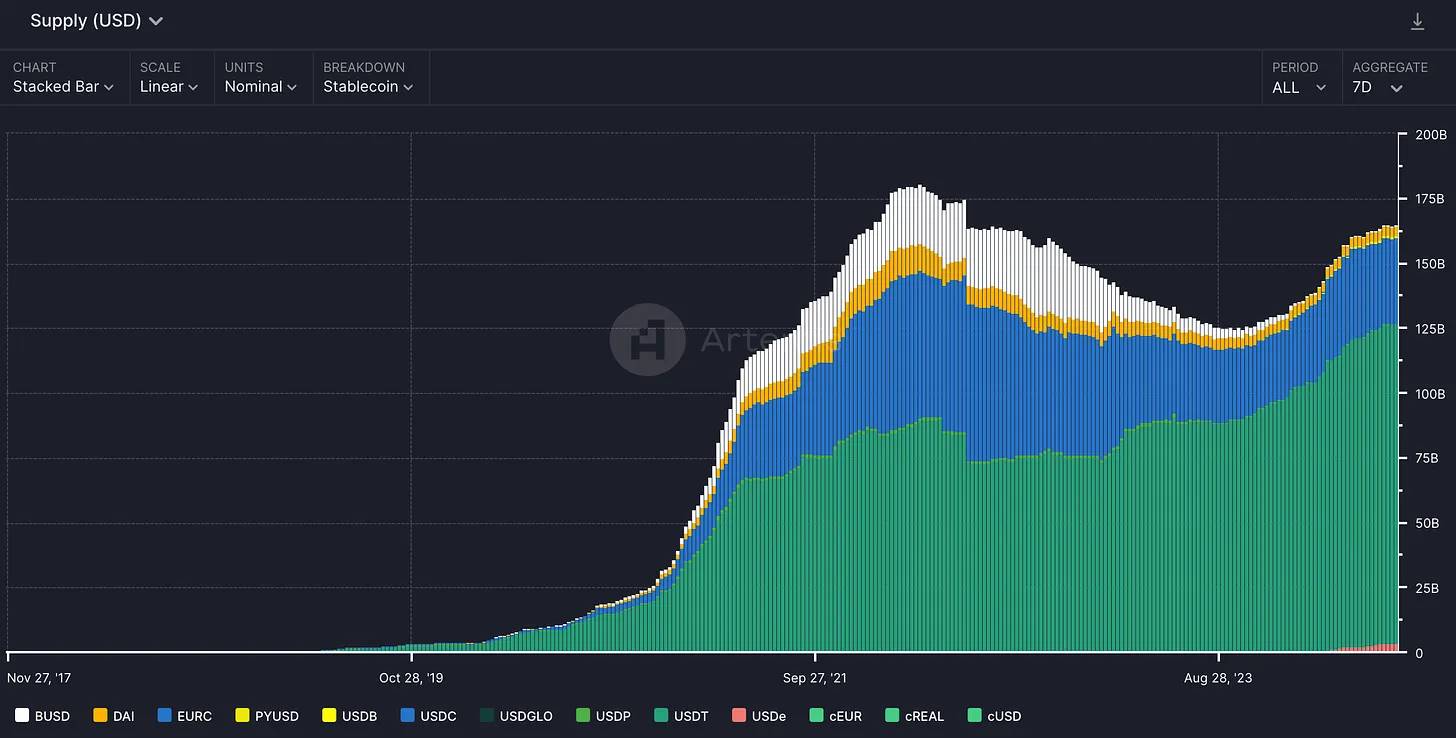

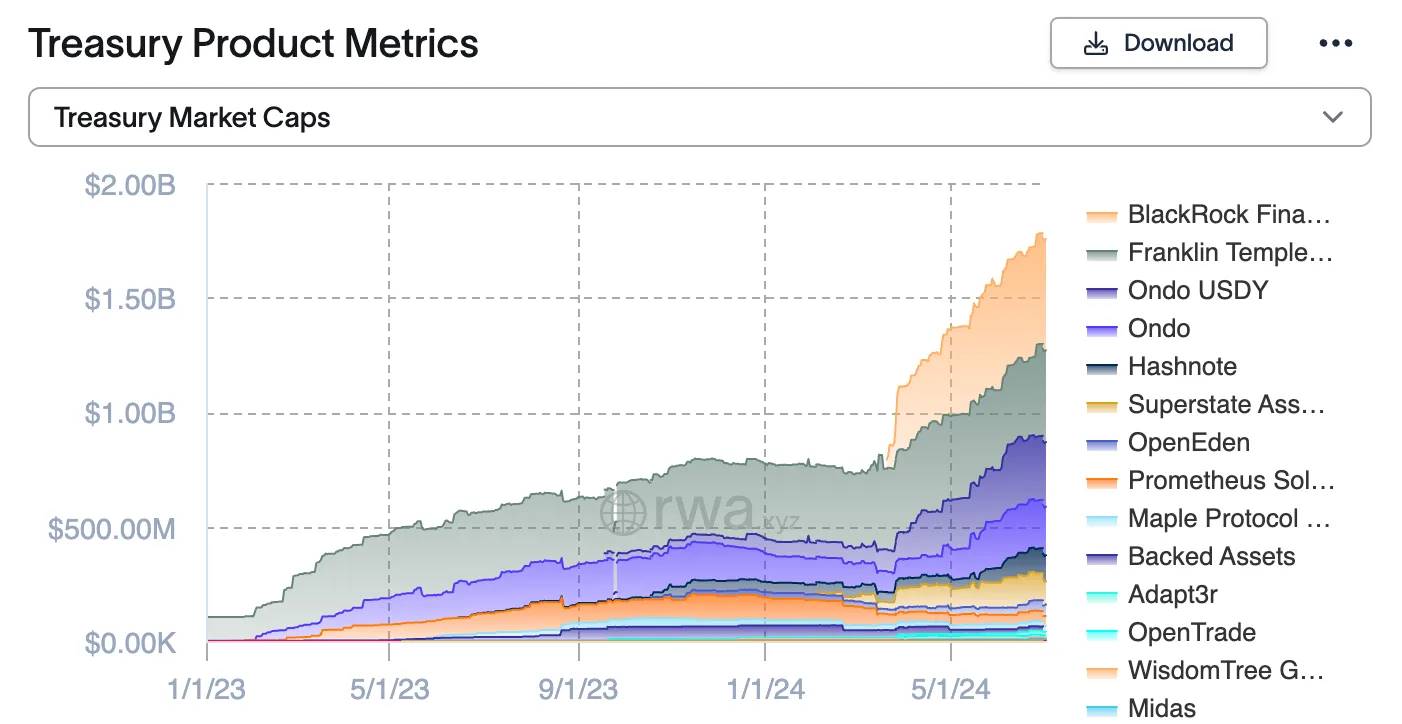

With over $160 billion in fiat currency tokenized as stablecoins and $2 billion in U.S. Treasuries and commodities tokenized, the tokenization of real-world financial assets on public blockchains has already begun.

Stablecoin Supply (Artemis)

Tokenized Treasury Supply by Issuer (rwa.xyz)

For years, the financial industry has shown interest in blockchain technology’s potential to disrupt traditional market infrastructure. Promised benefits include increased transparency, immutability, faster settlement times, improved capital efficiency, and reduced operational costs. These promises have led to the development of new financial instruments on blockchains, such as innovative trading mechanisms, lending protocols, and stablecoins. Today, decentralized finance (DeFi) holds over $100 billion in locked assets, signaling significant interest and investment in this space. Supporters of blockchain technology envision its impact extending beyond creating crypto assets like Bitcoin and Ethereum. They foresee a future where global, immutable, and distributed ledgers enhance existing financial systems—systems often constrained by centralized and siloed ledgers. At the core of this vision is tokenization: the process of representing traditional assets on a blockchain using smart contract programs known as tokens.

To understand the potential of this transformation, this article first examines the development and operation of traditional financial market infrastructure through the lens of securities clearing and settlement. This review includes a look back at historical developments and an analysis of current practices, providing essential context for exploring how blockchain-based tokenization could drive the next wave of financial innovation. The 1960s Wall Street paperwork crisis will serve as a critical case study, highlighting vulnerabilities and inefficiencies in existing systems. This historical episode will lay the foundation for discussing key players in clearing and settlement and the inherent challenges in today’s delivery versus payment (DvP) processes. The article concludes by discussing how permissionless blockchains may offer unique solutions to these challenges and unlock greater value and efficiency across the global financial system.

Wall Street's Paperwork Crisis and the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC)

Today’s financial system evolved gradually after decades of systemic strain. One often-overlooked event is the paperwork crisis of the late 1960s, which revealed why settlement systems evolved into their current form. George S. Geis details this episode in "The Historical Context of Stock Settlement and Blockchain." Understanding the evolution of securities clearing and settlement is crucial to comprehending today’s financial system and appreciating the significance of tokenization.

Today, individuals can easily buy securities within minutes via online brokers. However, this was not always the case. Historically, stocks were issued as physical certificates to individuals, with ownership represented by holding these certificates. To complete a stock transaction, the physical certificate had to be transferred from seller to buyer. This involved delivering the certificate to a transfer agent, who would cancel the old certificate and issue a new one in the buyer’s name. Once the new certificate was delivered to the buyer and the seller received payment, the trade was considered settled. In the 19th and 20th centuries, brokerage firms began holding stock certificates on behalf of investors, enabling easier clearing and settlement between brokerages. This process remained largely manual, with a brokerage typically requiring 33 different documents to execute and record a single securities transaction (SEC). While initially manageable, the process became increasingly cumbersome as trading volume grew. In the 1960s, stock trading activity surged, making the physical exchange of securities between brokerages impossible. A system designed to handle three million shares per day in the early 1960s could not cope with thirteen million shares traded daily by decade’s end (SEC). To give back offices time to catch up, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) shortened trading hours, extended settlement to T+5 (five business days after the trade), and eventually halted trading every Wednesday.

A stock certificate (Colorado Artifactual)

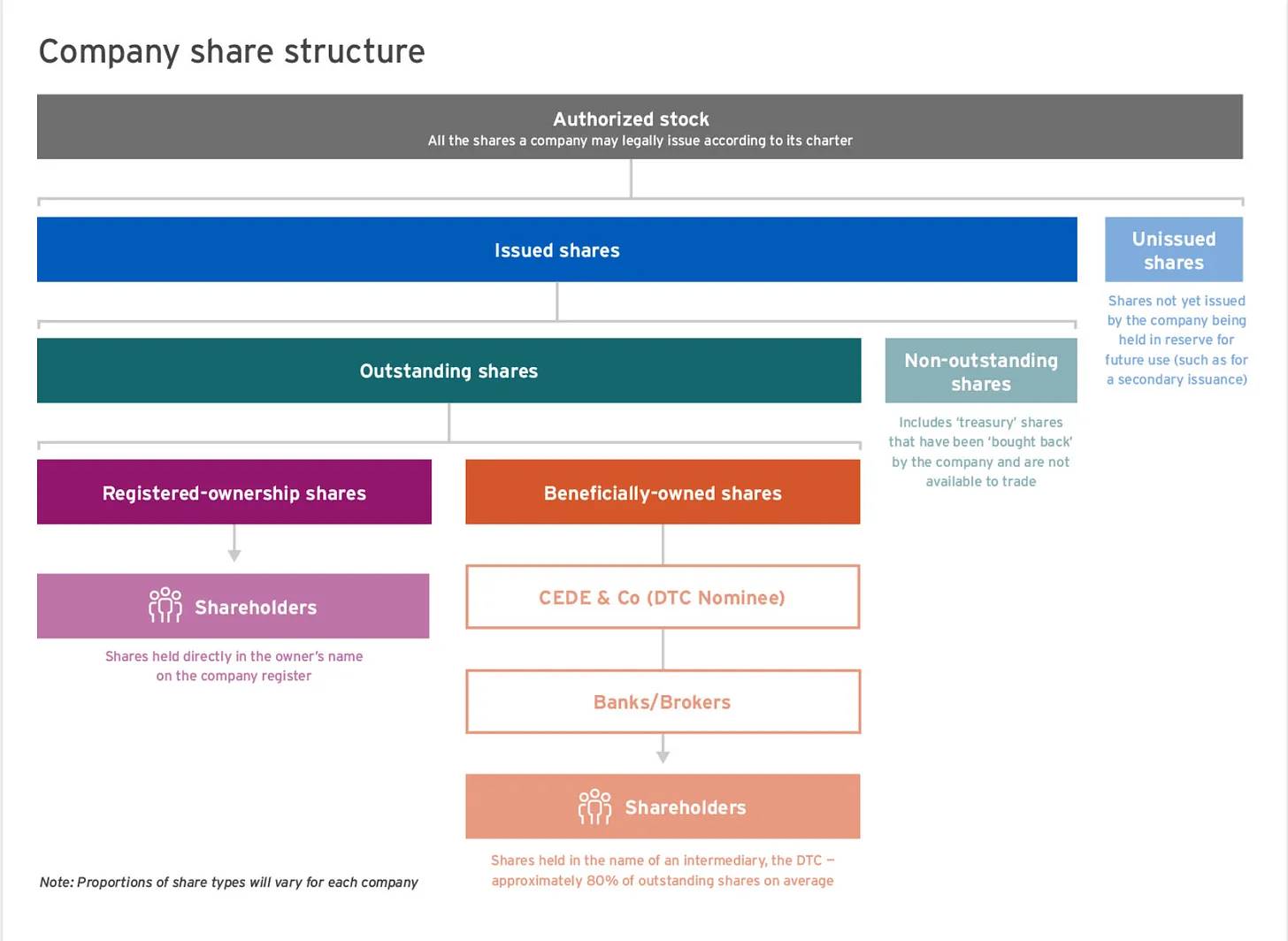

Starting in 1964, the NYSE sought a solution by creating the Central Certificate Service (CCS). CCS aimed to become a central depository for all stock certificates, holding them on behalf of its members—primarily broker-dealers—while ultimate investors gained beneficial ownership through book entries maintained by their brokers. Progress was hindered by regulatory constraints until 1969, when all fifty states amended their laws to allow CCS to centrally hold certificates and transfer ownership. All stock certificates were moved into CCS and stored as "immobilized fungible bulk." With all shares held in fixed form, CCS recorded internal ledger balances for its member brokerages, which in turn maintained ledger entries for the investors they represented. Now, stock settlements could occur via book entries rather than physical delivery. In 1973, CCS was renamed the Depository Trust Company (DTC), and all stock certificates were transferred into the name of its subsidiary, "Cede & Co." Today, DTC, through Cede, is the nominal owner of nearly all corporate stock. DTC itself is a subsidiary of the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC), whose other subsidiaries include the National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC). These entities—DTC and NSCC—are among the most critical components of today’s securities system.

The creation of these intermediaries transformed the nature of stock ownership. Previously, shareholders held physical certificates; now, ownership is represented through layers of book entries. As the financial system evolved, increasingly complex structures gave rise to more custodians and intermediaries, each maintaining their own ownership records via book entries. The layering of ownership is simplified in the diagram below:

Source: ComputerShare

Note on Securities Dematerialization

Following the paperwork crisis, DTCC ceased holding physical stock certificates in its vaults, transitioning shares from “immobilized” to fully “dematerialized,” meaning nearly all stocks are now represented solely as electronic book entries. Today, most securities are issued in dematerialized form. As of 2020, DTCC estimates that 98% of securities have been dematerialized, with the remaining 2% representing nearly $780 billion in securities.

An Introduction to Traditional Financial Market Infrastructures (FMIs)

To understand the potential of blockchain, it is necessary to understand financial market infrastructures (FMIs)—the very institutions blockchain aims to disrupt. FMIs are the backbone of our financial system. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) elaborate on the role of FMIs in the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMIs). BIS and IOSCO define the following key FMIs essential to the smooth functioning of the global financial system:

-

Payment Systems (PSs): Systems responsible for securely and efficiently transferring funds between participants.

-

Example: In the U.S., Fedwire is the primary interbank wire transfer system, offering Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) services. Globally, SWIFT is systemically important as it provides the messaging network for international fund transfers, though it is only a supporting system—it does not hold accounts or settle payments.

-

-

Central Securities Depositories (CSDs): Entities that provide securities accounts, central custody services, asset servicing, and play a key role in ensuring the integrity of securities issuance.

-

Example: In the U.S., DTC. In Europe, Euroclear or Clearstream.

-

-

Securities Settlement Systems (SSSs): Systems that enable the transfer and settlement of securities via book entries according to predetermined multilateral rules. These systems allow securities transfers to occur either with or without payment.

-

Example: In the U.S., DTC. In Europe, Euroclear or Clearstream.

-

-

Central Counterparties (CCPs): Entities that become the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer, ensuring the fulfillment of open contracts. CCPs achieve this by novating each bilateral contract into two separate contracts—one between the buyer and the CCP, and another between the seller and the CCP—thereby absorbing counterparty risk.

-

Example: In the U.S., the National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC).

-

-

Trade Repositories (TRs): Entities that maintain centralized electronic records of trade data.

-

Example: DTCC operates global trade repositories in North America, Europe, and Asia. Primarily used for derivatives trading.

-

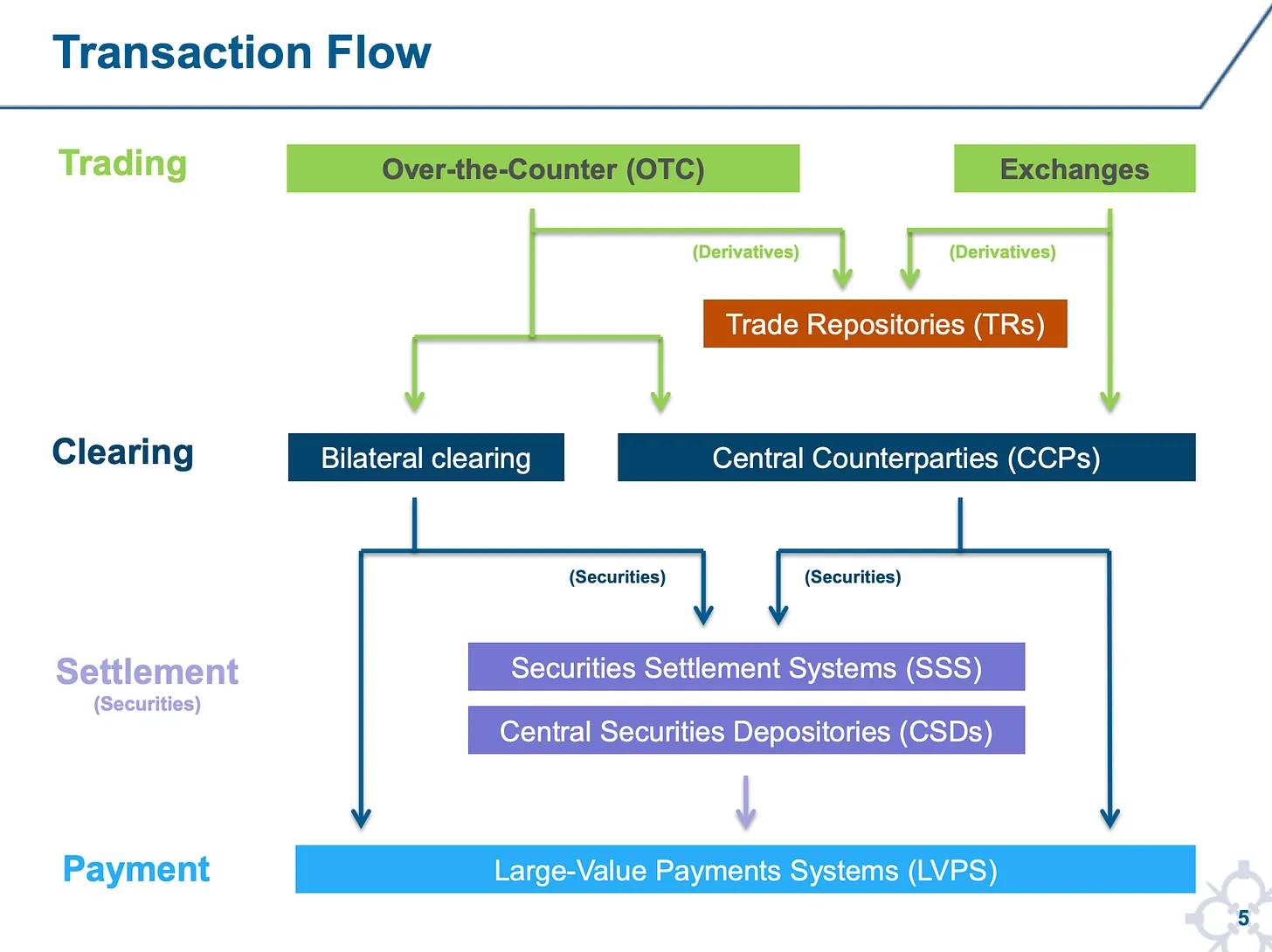

The interaction of these systems throughout the lifecycle of a trade is roughly illustrated in the diagram below:

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

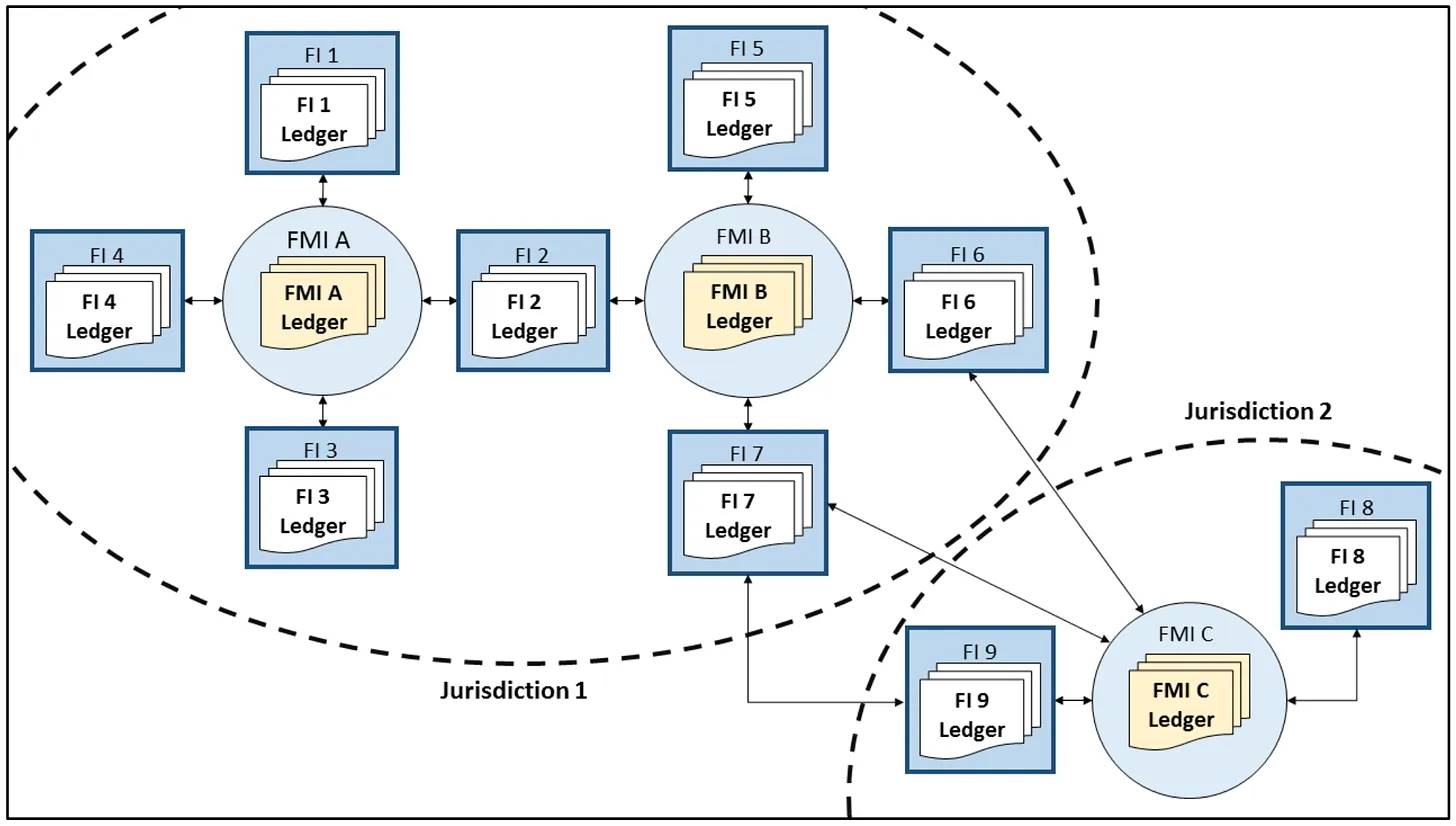

Typically, transfers are organized in a hub-and-spoke model, with FMI acting as the central hub and spokes being other financial institutions such as banks and broker-dealers. These institutions may interact with multiple FMIs across different markets and jurisdictions, as shown below:

Source: Federal Reserve

This siloing of ledgers means entities must trust one another to maintain the integrity of their books and their communication and reconciliation processes. There exist entities, procedures, and regulations purely to facilitate this trust. The more complex and globalized the financial system becomes, the more external forces are needed to enforce trust and cooperation among financial institutions and market intermediaries.

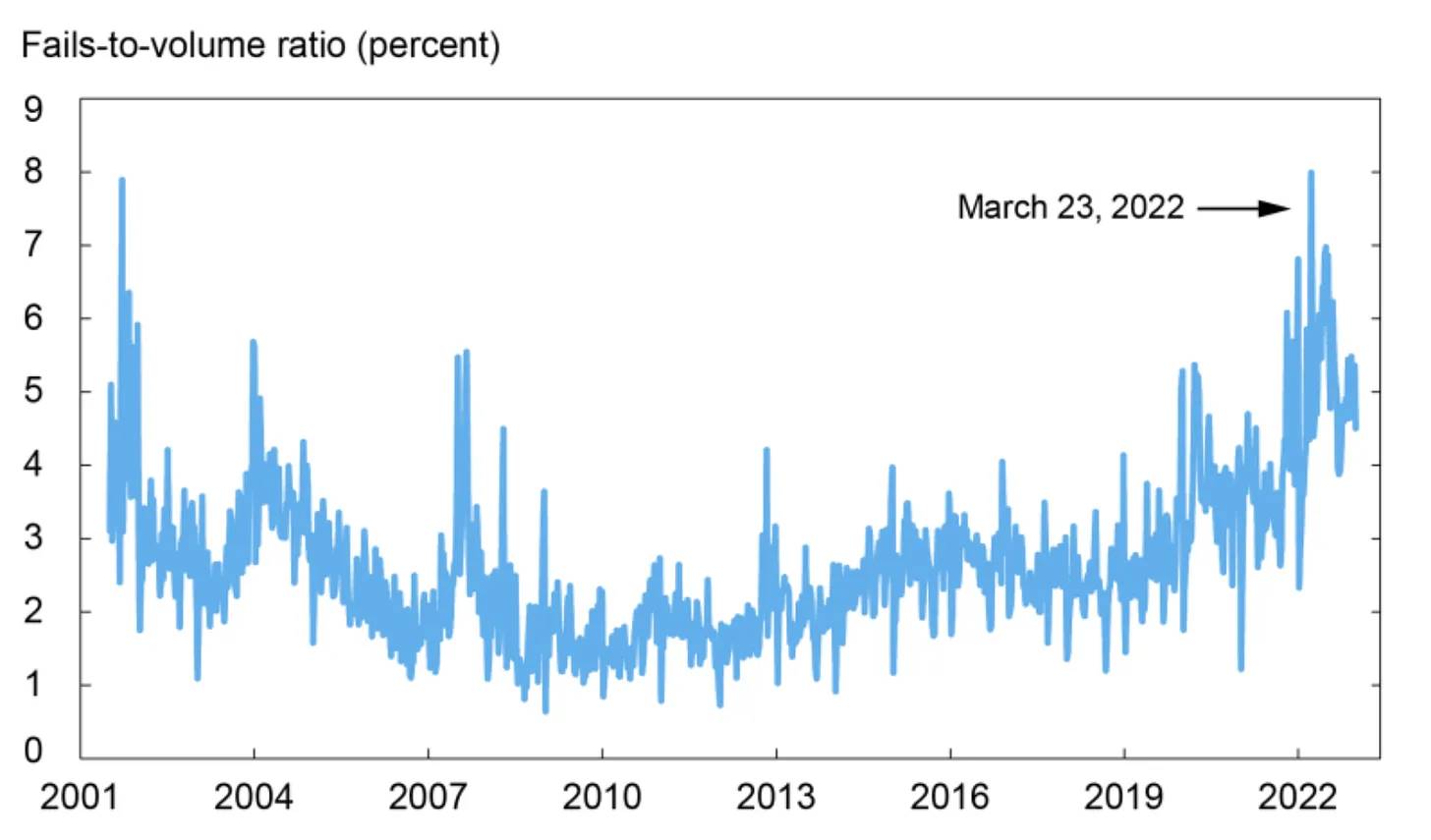

Current market inefficiencies are demonstrated by data on corporate securities settlement failures, which have recently risen to over 5% of total trading volume.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

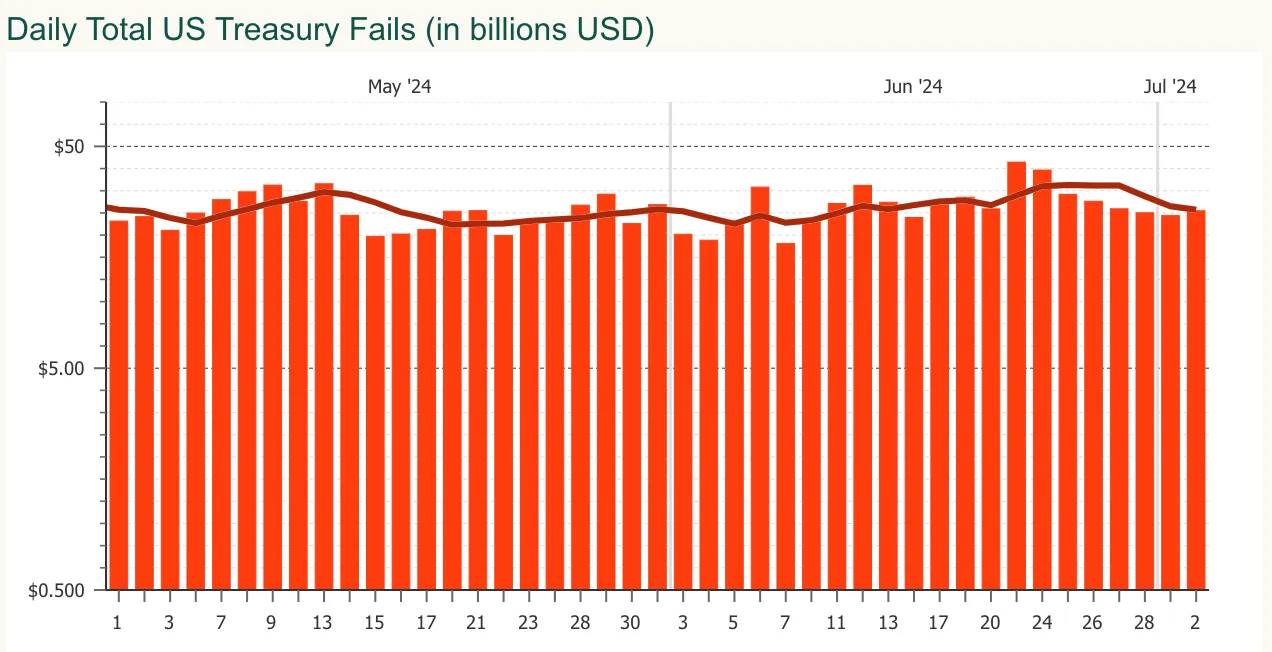

According to additional data provided by DTCC, daily U.S. Treasury settlement failures range between $20 billion and $50 billion. This represents approximately 1% of the $4 trillion in Treasury transactions DTCC clears daily.

Source: DTCC

Settlement failures carry consequences, as buyers of securities may have already pledged them as collateral in another transaction. That subsequent trade also risks failing, potentially triggering a cascade of failures.

Securities Settlement: Delivery Versus Payment

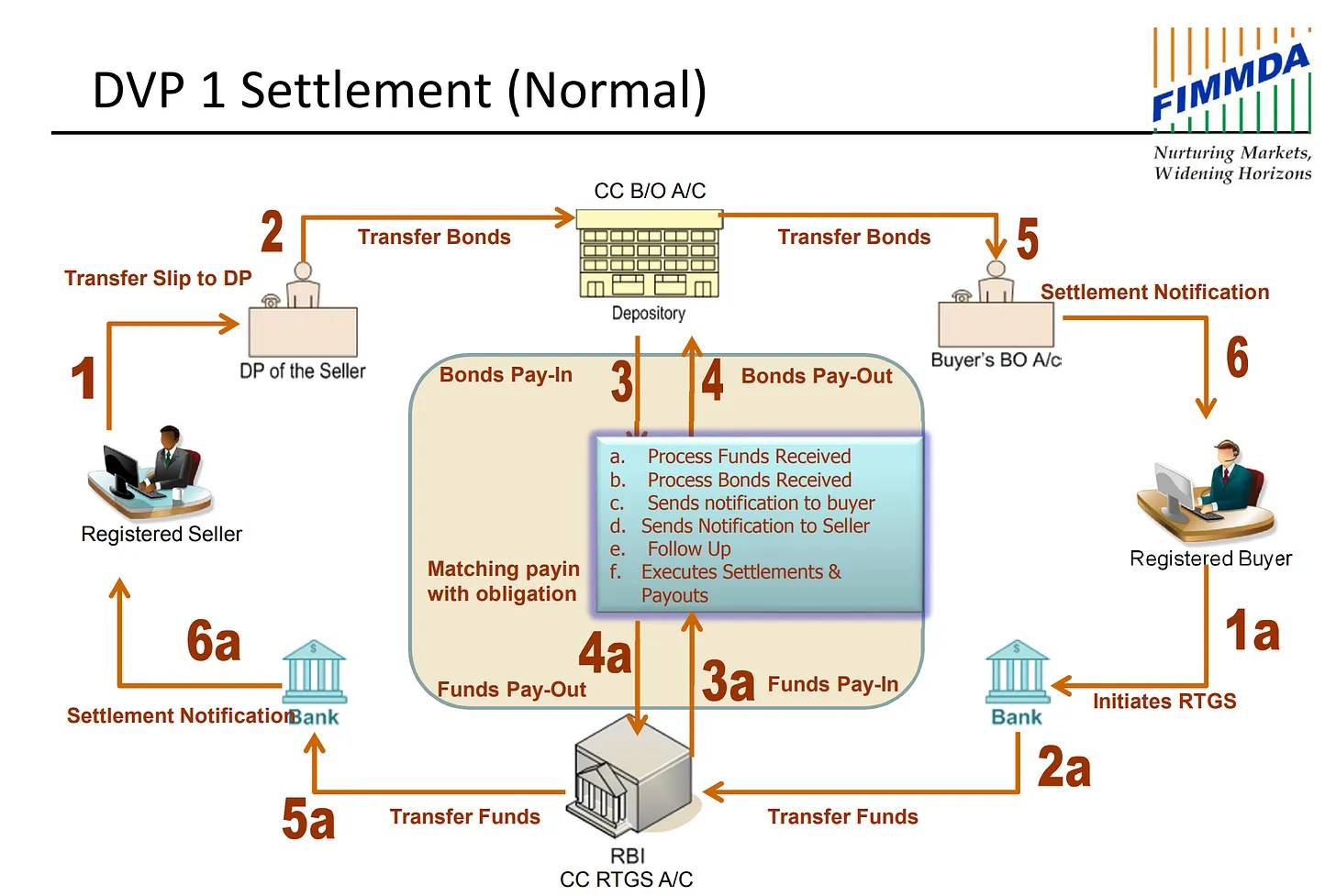

The Committee on Payments and Settlement Systems states that “the greatest financial risk in securities clearing and settlement occurs during settlement.” Securities can be transferred with or without payment. Some markets use a mechanism whereby securities transfer only occurs if the corresponding funds transfer succeeds—this is known as delivery versus payment (DvP). Today, securities delivery and funds payment occur in two fundamentally different systems: one via payment systems, the other via securities settlement systems and central securities depositories like DTC mentioned earlier. In the U.S., payments may go through FedWire or ACH, while international payments use SWIFT for messaging and settle via correspondent banking networks. On the other hand, securities delivery occurs through securities settlement systems and CSDs such as DTC. These are separate systems and ledgers, requiring increased communication and trust between different intermediaries.

Source: FIMMDA

Atomic Settlement on Blockchains and in DvP

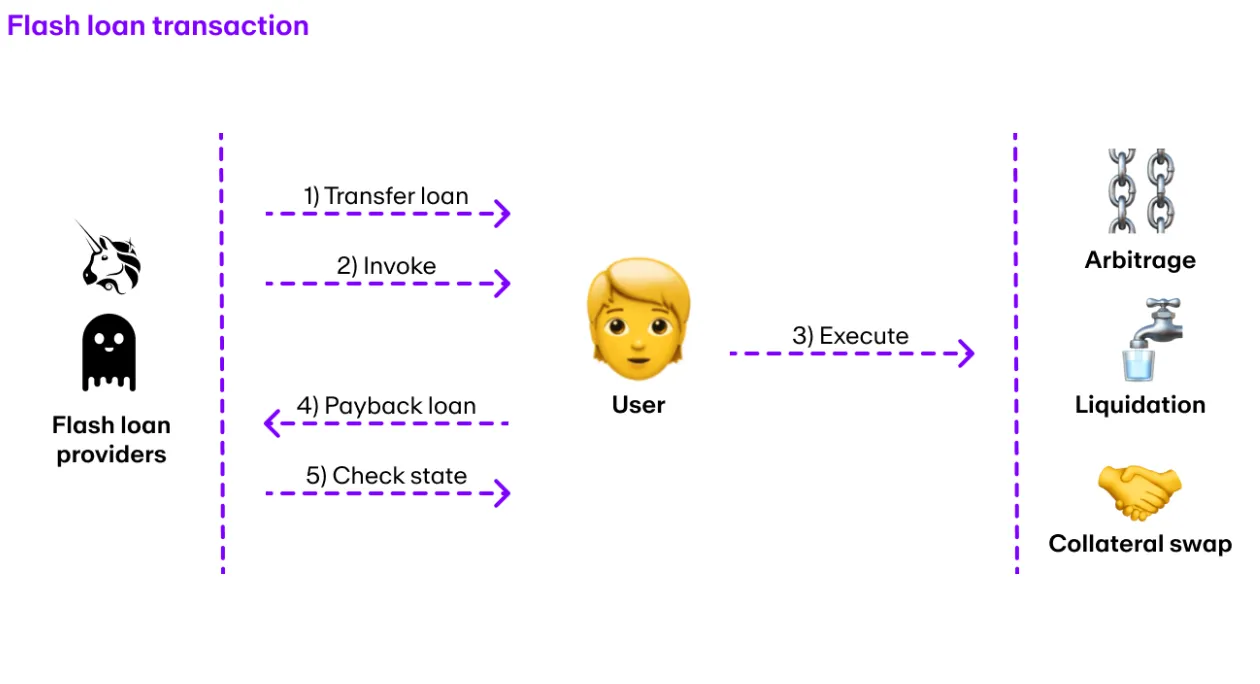

Blockchains can mitigate certain risks in DvP systems—such as principal settlement risk—through a unique property called atomicity. A blockchain transaction itself can consist of several distinct steps—for example, delivering a security and completing its payment. What makes blockchain transactions special is that either all parts of the transaction succeed, or none do. This property, known as atomicity, enables mechanisms like flash loans, where users can borrow without collateral in a single transaction, provided they repay it within the same transaction. This is possible because if repayment fails, the entire transaction—and thus the loan—is reverted. On blockchains, DvP can be executed trustlessly using smart contracts and the atomic execution of transactions. This has the potential to reduce principal settlement risk—the risk that one leg of a transaction fails, leaving parties exposed to potential losses. Blockchains possess key characteristics that make them capable of replacing the roles traditionally played by securities settlement systems and payment systems in DvP settlement.

Source: Moonpay

Why Permissionless Blockchains?

For a blockchain to be public and permissionless, anyone must be able to participate in validating transactions, producing blocks, and reaching consensus on the canonical state of the ledger. Additionally, anyone should be able to download the blockchain’s state and verify the validity of all transactions. Examples of public blockchains include Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Solana—anyone with internet access can interact with and access these ledgers. Blockchains meeting these criteria and achieving sufficient size and decentralization are inherently credibly neutral global settlement layers. That is, they are environments unbiased in transaction execution, validation, and settlement. By using smart contracts, transactions can be executed trustlessly and without intermediaries between unknown parties, resulting in an immutable, globally shared ledger. While no single entity can restrict individual access to the blockchain, applications built on top may implement permissions such as whitelisting for KYC and compliance purposes.

Public blockchains can improve back-office efficiency and capital efficiency by leveraging the programmability of smart contracts and the atomicity of blockchain transactions. These features can also be achieved on permissioned blockchains. To date, much enterprise and government exploration of blockchain has occurred via private and permissioned blockchains. This means validators must pass KYC checks to join the network and run software for consensus, transaction validation, and block production. Implementing permissioned blockchains for institutional use offers little advantage over private shared ledgers among institutions. If the underlying technology is fully controlled by entities such as JP Morgan, banking consortia, or even governments, the financial system ceases to be impartial and credibly neutral. Since 2016, enterprises and government agencies have studied distributed ledger technology, yet we have not seen significant deployment beyond pilot projects and test environments. According to Chris Dixon of a16z, part of the reason is that blockchains allow developers to write code that makes strong commitments—something enterprises are reluctant to do. Moreover, blockchains should resemble massive multiplayer games, not just multiplayer games like enterprise blockchains.

Case Studies in Tokenization

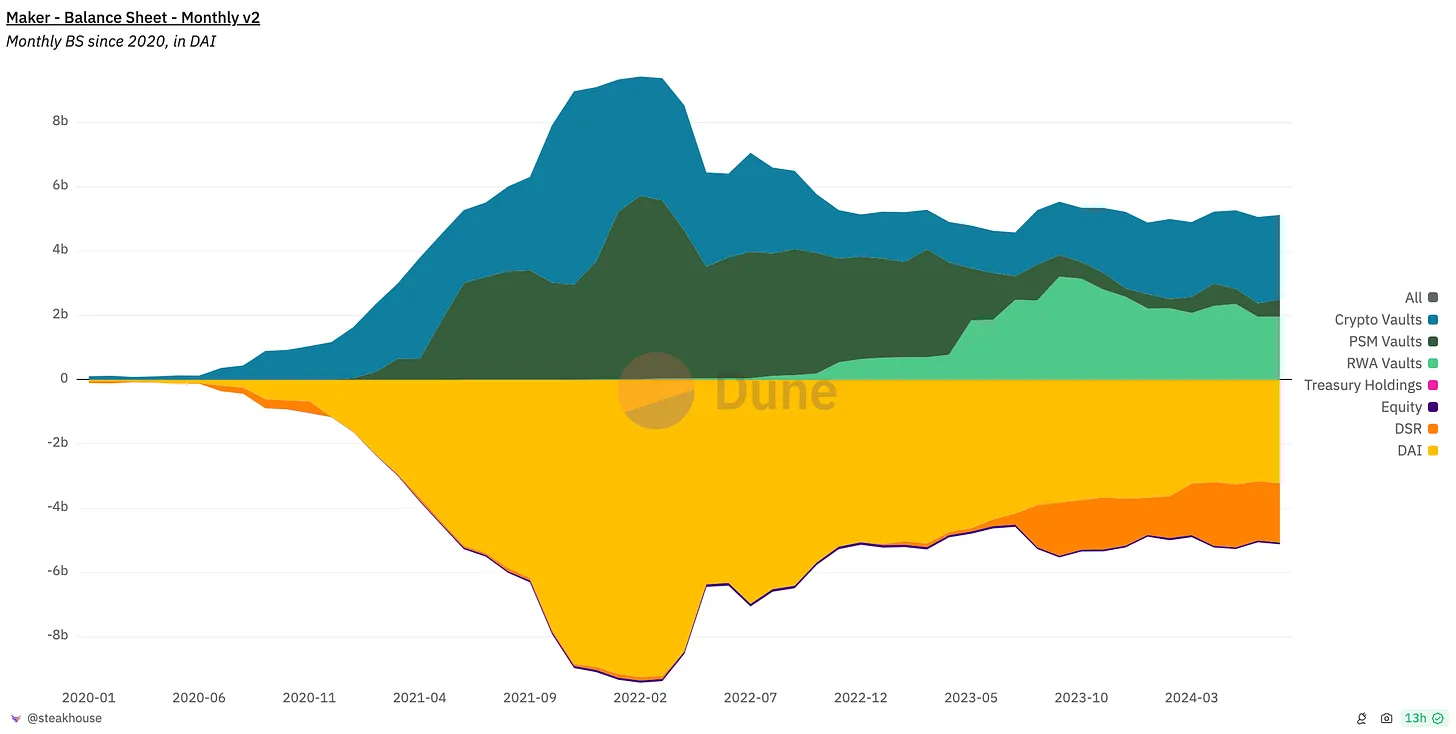

The Maker protocol, which manages the DAI stablecoin, has added real-world assets (RWAs) to collateralize DAI issuance. Previously, DAI was backed primarily by crypto assets and stablecoins. Today, about 40% of Maker’s balance sheet is allocated to RWA vaults investing in U.S. Treasuries, generating significant revenue for the protocol. These RWA vaults are managed by various entities including BlockTower and Huntingdon Valley Bank.

Source: Dune/steakhouse

BlackRock launched its USD Institutional Digital Liquidity Fund (BUIDL) on the public Ethereum blockchain in March 2024. The fund invests in U.S. Treasuries, and investors hold fund shares via ERC-20 tokens. To invest in the fund and issue additional shares, investors must first undergo KYC via Securitize. Share purchases can be made via wire transfer or USDC. While shares can be issued and redeemed using stablecoins, actual trade settlement only occurs after the fund successfully sells the underlying securities in traditional markets (in the case of redemptions). Furthermore, the transfer agent Securitize maintains an off-chain registry of transactions and ownership, which takes legal precedence over the blockchain. This indicates that numerous legal issues remain to be resolved before U.S. Treasuries themselves can be issued on-chain and atomically settled with USDC payments.

Ondo Finance is a fintech startup innovating in the tokenization space. It offers several products including OUSG and USDY, issued as tokens on multiple public blockchains. Both products invest in U.S. Treasuries and offer yield to holders. OUSG is available in the U.S. only to qualified purchasers, while USDY is open to anyone outside the U.S. and other restricted regions. An interesting point about USDY minting is that when users wish to mint USDY, they can choose to deposit either USD via wire transfer or USDC. For USDC deposits, the transfer is considered “completed” once Ondo converts the USDC to USD and sends the funds into its own bank account. This reflects legal and accounting considerations, clearly indicating that the lack of a clear regulatory framework for digital assets hinders innovation.

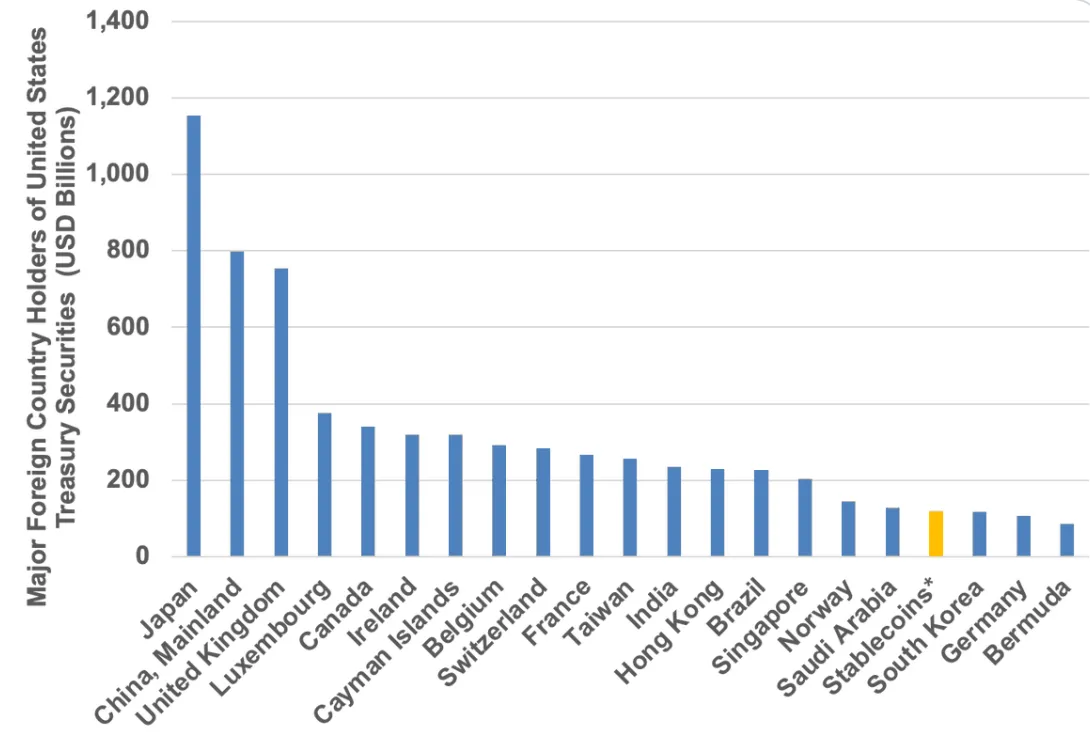

To date, stablecoins represent the most successful case of tokenization. Over $165 billion in tokenized fiat exists as stablecoins, with monthly transaction volumes reaching several trillions. Stablecoins are becoming an increasingly important component of financial markets. Collectively, stablecoin issuers rank as the 18th largest holder of U.S. debt worldwide.

Source: Tagus Capital

Conclusion

The financial system has endured many growing pains, including the paperwork crisis, the global financial crisis, and even the GameStop episode. These periods stress-tested the system and shaped it into what it is today—a vast network of intermediaries and siloed systems relying on slow processes and regulations to establish trust and conduct transactions. Public blockchains offer a better alternative by building censorship-resistant, credibly neutral, and programmable ledgers. However, blockchains are not perfect either. Due to their distributed nature, they suffer from technical-specific issues such as block reorganizations, forks, and latency-related problems. For a deeper understanding of settlement risks associated with public blockchains, see Natasha Vasan’s Settling the Unsettled. Moreover, despite improvements in smart contract security, smart contracts continue to be hacked or exploited through social engineering. Blockchains also become expensive during high congestion periods and have yet to prove their ability to scale to the transaction volumes required by a global financial system. Finally, widespread tokenization of real-world assets requires overcoming compliance and regulatory hurdles.

With appropriate legal frameworks and sufficiently mature underlying technology, asset tokenization on public blockchains has the potential to unlock network effects as assets, applications, and users converge. As more assets, applications, and users come on-chain, the platforms themselves—and the blockchains—become more valuable, attracting builders, issuers, and users in a virtuous cycle. Using a globally shared, credibly neutral foundational technology will enable entirely new applications in finance and commerce. Today, thousands of entrepreneurs, developers, and policymakers are building this public infrastructure, overcoming obstacles to create a more interconnected, efficient, and fairer financial system.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News