Vitalik's 30th Birthday Reflection: My Childhood Has Come to an End

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's 30th Birthday Reflection: My Childhood Has Come to an End

I'm now playing a different role, and it's time for the next generation to take up the mantle that once belonged to me.

Written by: Vitalik Buterin

Translated by: TechFlow

Introduction:

Thirty years old.

Today is Vitalik's 30th birthday. On this significant milestone, he published a long-form essay titled "The end of my childhood."

Reading through the piece, Vitalik reflects on various themes including Ethereum’s technology, the current state of the crypto world, the Russia-Ukraine war, life and death, personal growth, and accumulated experiences. He also frankly states:

"I now play a different role. It's time for the next generation to take up the mantle that once belonged to me."

As a central figure in the crypto space, Vitalik has traveled extensively over the past years, living as a digital nomad while putting his technological ideals into practice. Through exposure to diverse cultures around the world, he has gained deeper insights and a stronger sense of responsibility.

"Cryptocurrency is not just a financial story—it can be part of a broader narrative about building better technologies."

This essay serves as a comprehensive retrospective and forward-looking reflection from Vitalik at age 30—an emotionally honest and intellectually rich exploration of both personal journey and the wider crypto landscape.

TechFlow has translated the full article for our readers.

One of my most vivid memories over the past two years was speaking at hackathons, visiting hacker houses, doing Zuzalu in Montenegro, and seeing people ten years younger than me taking leadership roles across various projects—as organizers or developers—in areas like crypto audits, Ethereum layer-2 scaling, synthetic biology, and more. One of the memes of Zuzalu’s core organizing team was 21-year-old Nicole Sun; a year earlier, she invited me to visit a hacker house in Korea—a gathering of about thirty people—where I remember it being the first time I realized I was the oldest person in the room.

When I was the same age as today’s hacker house residents, I remember many people praising me as one of those world-changing, brilliant young prodigies like Zuckerberg.

Now I cringe a bit at that—not only because I dislike such attention, but also because I don’t understand why people have to translate “wunderkind” into German when the English version works perfectly fine. But watching all these individuals go further and achieve more at an even younger age makes it clear: if that was ever my role, it no longer is. I now play a different role. It's time for the next generation to take up the mantle that once belonged to me.

August 2022, the path leading to the Seoul hacker house. I took this photo because I couldn't tell which house I was supposed to enter, so I was communicating with the organizers to get clarification. Of course, the actual house wasn't on this street at all, but about twenty meters to the right in a much more visible location.

1

As someone who supports radical life extension (meaning, conducting medical research so humans could literally live thousands or even millions of years), people often ask me: isn't the meaning of life deeply tied to its finiteness—that you have only a limited amount, so you must cherish and enjoy it?

Historically, my instinct has been to reject this idea: while psychologically we tend to value things more when they are finite or scarce, it seems absurd to suggest that enduring grievances might be so terrible that they're worse than literal nonexistence. Also, I sometimes think that even if immortality turned out to be that bad, we could always just choose to start more wars to simultaneously increase our “excitement” and shorten our lifespans. The fact that non-sociopaths among us reject this option today strongly suggests to me that we would also reject it once it becomes a real choice—just as we do regarding biological death and suffering.

However, as I’ve aged, I realize I don’t even need to argue this anymore.

Whether our lives as a whole are finite or infinite, every good thing within our lives is finite. Friendships you thought were eternal slowly fade into the mists of time. Your personality can completely change within ten years. Cities can transform entirely, for better or worse. You can move to a new city yourself and restart the process of familiarizing yourself with the physical environment from scratch. Political ideologies are finite: you might build your entire identity around views on top marginal tax rates and public healthcare, only to feel utterly lost ten years later when people seem to no longer care about these topics at all, spending all their time instead discussing “wokeness,” “bronze age mindset,” and “e/acc.”

A person’s identity is always tied to their role in the broader world around them. Over the course of a decade, not only does the individual change, but the world around them changes too. One shift I’ve written about before is how my thinking now involves less economics compared to ten years ago. The main reason for this shift is that during the first five years of my crypto career, I spent a large portion of my time trying to invent mathematically provable optimal governance mechanisms, eventually discovering some fundamental impossibility results that made it clear to me that:

(i) what I was looking for was impossible, and (ii) the most important variables determining whether flawed systems succeed in practice—the degree of coordination among subgroups of participants, along with other factors we often simplify as “culture”—were variables I hadn’t even modeled.

Previously, mathematics was a central part of my identity: I participated heavily in math competitions in high school; shortly after entering crypto, I began doing extensive coding for Ethereum, Bitcoin, and beyond; I got excited about every new cryptographic protocol, and to me, economics was part of a broader worldview—it was a mathematical tool for understanding and improving the social world. All the pieces fit together neatly.

Now, those pieces fit together less often. I still use math to analyze social mechanisms, though more often aiming to make rough initial guesses about what might work and mitigate worst-case behaviors (which in reality are often carried out by bots rather than humans), rather than explaining average-case behavior. Now, much of my writing and thinking—even when supporting ideals similar to those I backed a decade ago—often uses very different arguments.

One thing that fascinates me about modern AI is how it allows us to engage mathematically and philosophically with hidden variables guiding human interactions: AI can make “resonance” clearly legible.

All these deaths, births, and rebirths—of ideas or groups of people—are ways in which life is finite. These deaths and rebirths will continue in a world where we live for two centuries, a thousand years, or as long as main-sequence stars. If you personally feel life lacks enough finiteness, death, and rebirth, you don’t need to start a war to add more—you can also make the same choice I did and become a digital nomad.

2

"Grads are falling in Mariupol."

I still remember exactly 7:20 PM local time on February 23, 2022, anxiously staring at my laptop screen in a Denver hotel room. For the previous two hours, I had been scrolling Twitter for updates while repeatedly messaging my father, who shared the same thoughts and fears, until he finally sent me that decisive reply. I posted a tweet stating my position on the issue as clearly as possible, and stayed up late that night.

The next morning, I woke up to see the Ukrainian government’s Twitter account desperately requesting cryptocurrency donations. At first, I didn’t believe it could be real—I was extremely worried the account had been cleverly hacked: someone, perhaps the Russian government itself, exploiting everyone’s confusion and desperation to steal some money. My “security mindset” kicked in immediately, and I started tweeting warnings, while simultaneously reaching out through my network to find someone who could confirm or deny whether the ETH address was legitimate. An hour later, I became convinced it was real, and publicly shared my conclusion. About an hour after that, a family member messaged me pointing out that given what I’d already done, for my own safety, I probably shouldn’t return to Russia.

Eight months later, I witnessed another upheaval in the crypto world: the public collapse of Sam Bankman-Fried and FTX. Someone on Twitter then posted a long list of “crypto protagonists,” showing who had fallen and who remained standing. The casualty rate on that list was high:

The SBF case wasn’t unique—it echoed MtGox and previous major crypto crises. But it was a moment when it hit me: most of the people I once saw as guiding lights of the crypto world, figures I could comfortably follow since 2014, were now gone.

People who view me from a distance often assume I’m highly agentic, probably because that’s what you expect from a “college dropout” “protagonist” or “project founder.” In reality, however, I’m far from that. The virtue I cherished as a child wasn’t the creativity of starting a unique new project, nor courage when needed, but the virtue of being a good student: showing up on time, doing homework, getting 99% averages.

My decision to drop out wasn’t a bold step taken out of conviction. It began in early 2013, when I decided to spend the summer interning at Ripple. When complications with the U.S. visa prevented that, I instead spent the whole summer working with Mihai Alisie, my boss and friend from the Bitcoin Magazine in Spain. By late August, I decided I wanted more time exploring the crypto world, so I extended my break to 12 months. It wasn’t until January 2014, when I saw hundreds cheering my talk introducing Ethereum at BTC Miami, that I finally realized I had chosen to leave college permanently. Most of my decisions in Ethereum involved responding to others’ pressures and requests. When I met Vladimir Putin in 2017, I didn’t arrange the meeting myself—it was suggested by someone else, and I almost reflexively said “sure.”

Now, five years later, I finally realize: (i) I was complicit in legitimizing a genocidal dictator, and (ii) within crypto, I no longer have the luxury of sitting back and letting those mysterious “others” lead everything.

These two events, despite differing greatly in type and scale of tragedy, left similar lessons imprinted in my mind: I actually bear responsibility in this world, and I need to consciously reflect on how I operate. Doing nothing, or living on autopilot, simply becoming part of someone else’s plan, is not automatically safe or even blameless.

I am one of the mysterious others. It falls to me to play this role. If I don’t, the crypto space will either stagnate or be dominated by opportunistic money grabbers—and then I’ll have only myself to blame. Hence, I’ve decided to cautiously accept fewer outside plans, and be more intentional about pushing my own: fewer ill-considered meetings with random powerful people who only want me as a source of legitimacy, and more initiatives like Zuzalu.

Zuzalu flag in Montenegro, spring 2023

3

Now let’s turn to something happier—or at least challenges more akin to mathematical puzzles rather than tripping while running and having to walk two kilometers with bleeding knees to seek medical help. The author declines to share more details, noting the internet is already very good at turning a photo of a rolled-up USB cable in his pocket into suggestive online memes, and certainly doesn’t want to give those people more “ammunition.”

I’ve previously discussed the changing role of economics, the need to rethink motivation (and coordination—we’re social animals, so the two are closely linked), and the idea of the world becoming a “dense jungle”: big governments, big corporations, big mobs, and nearly any “big XX” will keep growing, and their interactions will become increasingly frequent and complex. I haven’t talked much yet about how many of these changes affect the crypto space itself.

Crypto was born in late 2008, after the global financial crisis. Bitcoin’s genesis block famously references this headline from The Times of London:

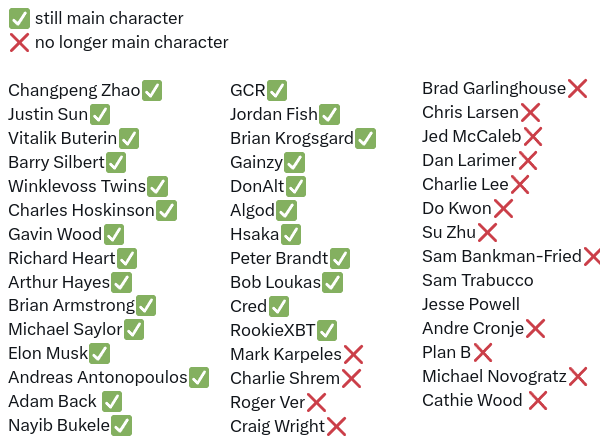

Early Bitcoin memes were deeply influenced by these themes. Bitcoin aimed to abolish banks—good, because banks are unsustainable behemoths constantly creating financial crises. Bitcoin existed to abolish fiat currency, because without central banks and their issued fiat, the banking system couldn’t exist—plus, fiat enables money printing, which funds wars. But in the fifteen years since, the broader public discourse overall seems to have largely moved beyond concerns about money and banks. What matters now? Well, we can ask a copy of Mixtral 8x7b running on my new GPU laptop:

Again, AI can make resonance legible.

No mention of money, banks, or government control of currency. Trade and inequality are listed as global concerns, but as far as I can tell, the issues and solutions being discussed happen more in the physical world than the digital. Is crypto’s original “story” increasingly falling out of date?

There are two sensible responses to this puzzle, both of which I believe our ecosystem would benefit from:

-

Remind people that money and finance still matter, and serve underserved populations well within this niche.

-

Go beyond finance, using our technologies to build a more comprehensive vision: a freer, more open, more democratic alternative tech stack, and tools to help build a broader better society—or at least aid those excluded from mainstream digital infrastructure.

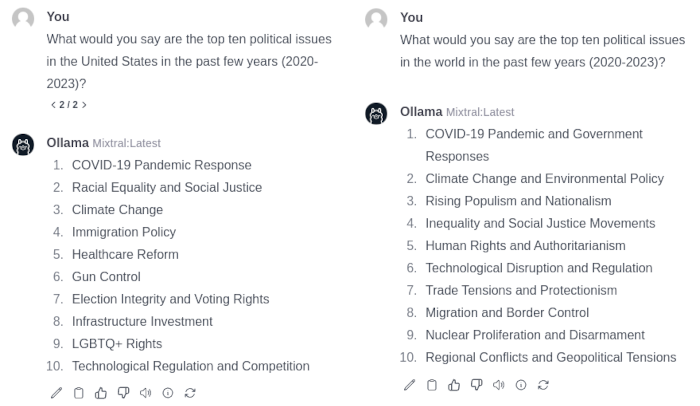

Importantly, I believe crypto has unique advantages in delivering value here. Cryptocurrency is one of the few genuinely highly decentralized tech industries, with developers spread globally:

Source: Electric Capital’s 2023 Crypto Developer Report

Over the past year, I’ve visited many emerging global crypto hubs, and I can confirm this is indeed the case. More and more major crypto projects are headquartered all over the world—or nowhere at all. Moreover, non-Western developers often have unique advantages in understanding the specific needs of crypto users in low-income countries and creating products that meet those needs. When I speak with many people from San Francisco, I get a clear impression: they think AI is the only important thing, SF is the capital of AI, therefore SF is the only important place. “So, Vitalik, why haven’t you settled in the Bay Area with an O1 visa yet?” Crypto doesn’t need to play this game: the world is large. Just one trip to Argentina, Turkey, or Zambia reminds you that many people still face critical issues related to access to money and finance, and there remains ample opportunity to do the complex work of balancing user experience with decentralization to solve these problems sustainably.

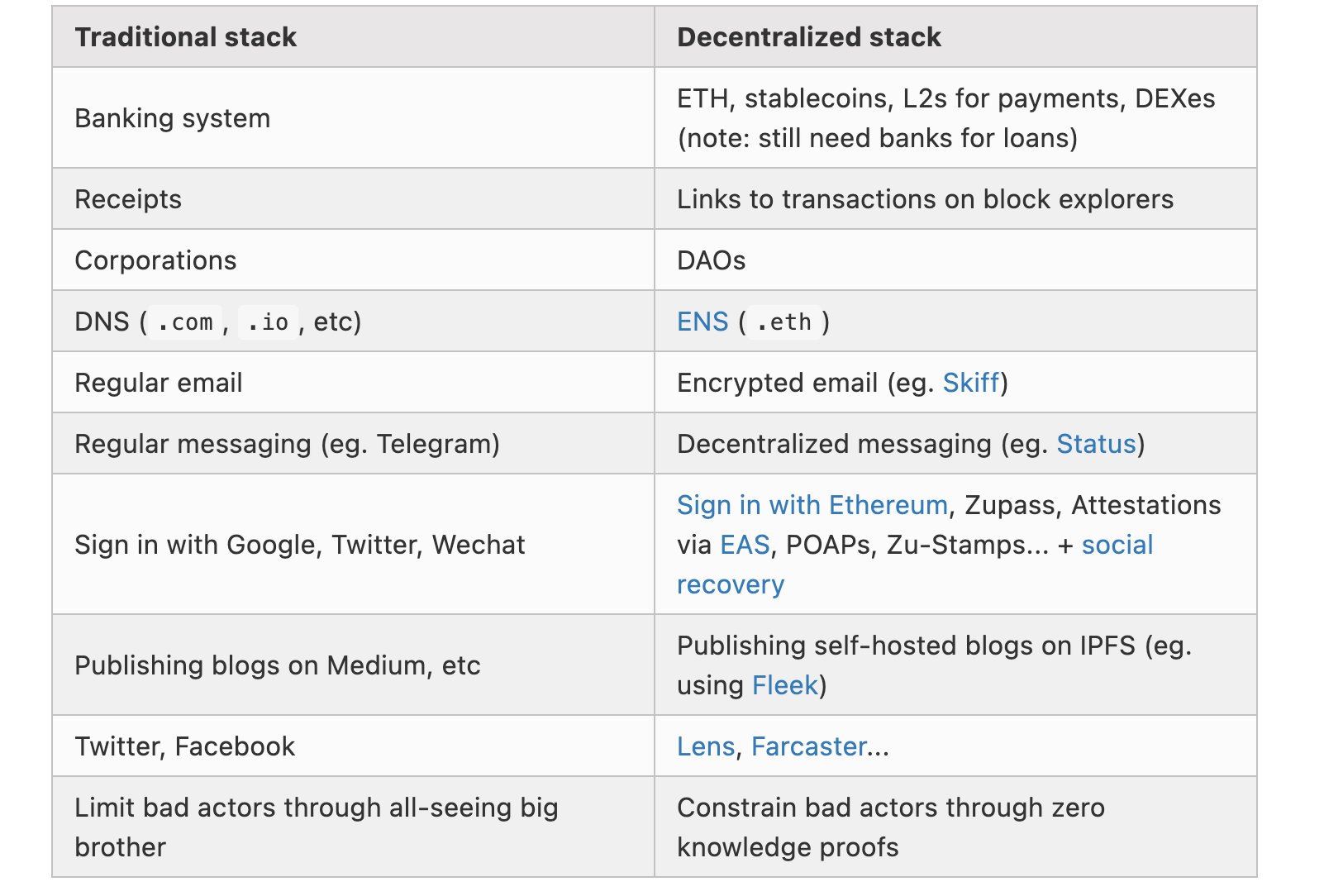

Another vision I outlined in a recent post is “Make Ethereum Cypherpunk Again.” Rather than focusing solely on money or becoming the “internet of value,” I believe the Ethereum community should broaden its horizons. We should build a complete decentralized tech stack—one independent of the traditional Silicon Valley stack to a degree comparable to, say, China’s tech stack—and compete with centralized tech companies at every level.

Reposting the tech stack comparison chart again:

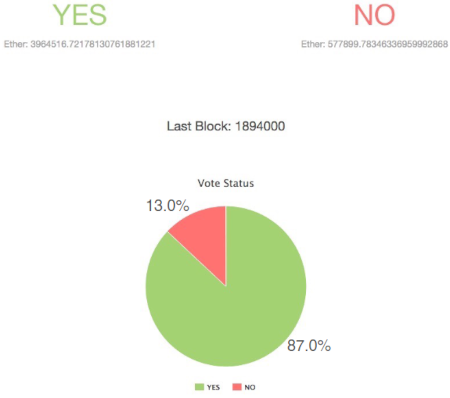

After publishing that article, some readers reminded me of an important missing component in this stack: democratic governance technologies—tools for collective decision-making. This is something centralized tech genuinely attempts to provide, assuming each company is run by a CEO, overseen by... uh... a board of directors. Ethereum has benefited in the past from very primitive democratic governance tools: when a series of controversial decisions—like the DAO fork and several rounds of issuance reduction—were made in 2016–2017, a team from Shanghai created a platform called Carbonvote, where ETH holders could vote on decisions.

ETH voting on the DAO fork

Votes were purely advisory: no hard consensus determined outcomes. But they helped core developers gain confidence to implement a series of EIPs, knowing broad community support existed. Today, we have far richer proofs of community membership than token holdings: POAPs, Gitcoin Passport scores, Zu stamps, etc.

Putting it all together, we can begin to see a second vision for how crypto can evolve to better address 21st-century concerns and needs: building a more comprehensive, trustworthy, democratic, and decentralized tech stack. Zero-knowledge proofs are key to expanding the scope of what this stack can offer: we can move beyond the false binary of “anonymous and thus untrustworthy” vs. “verified and KYC’d,” and prove finer-grained statements about who we are and what permissions we hold. This lets us address both authenticity and manipulation concerns—protection against the “Big Brother outside”—and privacy concerns—protection against the “Big Brother inside.” Thus, cryptocurrency is not just a financial story; it can be part of a broader story about creating better technology.

4

But beyond storytelling, how do we achieve this goal? Here, we return to questions I raised in a post three years ago: shifting motivations. Often, those overly focused on financial incentive theories—or at least a theory where financial incentives can be understood and analyzed, while everything else is treated as a mysterious black box called “culture”—are puzzled by this space, because so much behavior seems contrary to financial incentives. “Users don’t care about decentralization,” yet projects still strive to decentralize. “Consensus is based on game theory,” yet successful social campaigns pushing people out of dominant mining or staking pools have worked in both Bitcoin and Ethereum.

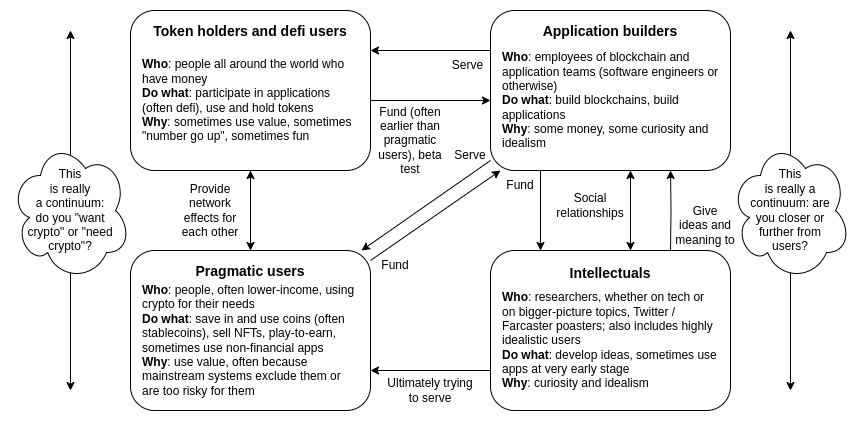

I recently realized that, to my knowledge, no one has tried to create a foundational, functional map of the crypto space that works “as intended,” attempting to include more participants and motivations. So let me quickly try one now:

This map is an intentional 50/50 mix of idealism and “describing reality.” It aims to show four main components of the ecosystem and their supportive, symbiotic relationships. In practice, many crypto entities are hybrids of these four.

Each of these four parts provides something essential to the whole:

-

Token holders and DeFi users contribute greatly to funding the entire ecosystem, crucial for advancing technologies like consensus algorithms and zero-knowledge proofs to production quality.

-

Intellectuals provide ideas, ensuring the space actually does meaningful things.

-

Builders bridge gaps, trying to develop applications for users and put ideas into practice.

-

Pragmatic users are who we ultimately serve.

Each group has complex motivations, interacting with others in intricate ways. There are also dysfunctional versions of each group: apps may be exploitative, DeFi users might unintentionally reinforce exploitative app network effects, pragmatic users may deepen reliance on centralized workflows, intellectuals may become too theoretical, obsessed with solving every problem by accusing people of “inconsistency,” failing to recognize financial incentives (and disincentives from “user friction”) matter too, and these can and should be addressed.

Often, these groups tend to mock each other, and sometimes I’ve played a part in that. Some blockchain projects openly try to shed what they see as naive, utopian, distracting idealism, focusing directly on applications and usage. Some developers look down on their token holders and their dirty love of making money. Others look down on pragmatic users and their dirty willingness to use centralized solutions when more convenient.

But I believe there’s an opportunity to foster greater understanding among these four groups, where each side recognizes its ultimate dependence on the other three, strives to limit its excesses, and sees that their dreams aren’t as distant as they imagine. I think this kind of peace is actually achievable—not only within “crypto” but also between it and adjacent communities that share aligned values.

5

The beauty of crypto’s global nature is that it gives me a window into fascinating cultures and subcultures worldwide, and how they interact with the crypto world.

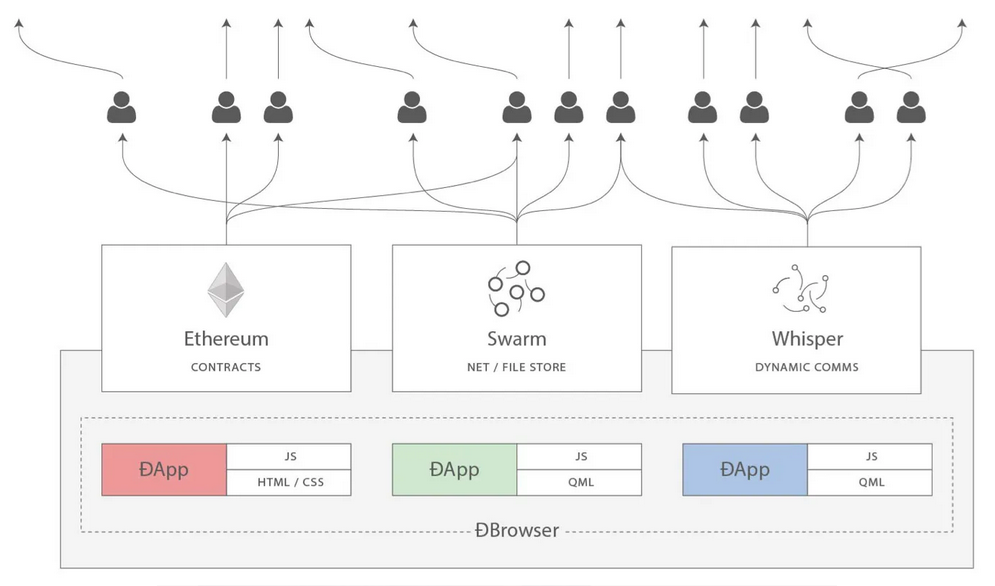

I still remember my first visit to China in 2014, seeing all signs of brightness and hope: exchanges scaling to hundreds of employees, faster than in the U.S., large-scale GPU and later ASIC mining pools, and projects with millions of users. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley and Europe had long been the primary engines of idealism in the field, albeit in two distinct styles. Almost from the beginning, Ethereum’s de facto headquarters was in Berlin, and it was within Europe’s open-source culture that many early ideas about using Ethereum for non-financial applications emerged.

Ethereum diagram and two proposed non-blockchain sister protocols Whisper and Swarm, frequently used by Gavin Wood in his early presentations

Silicon Valley (of course, referring to the entire San Francisco Bay Area) was another early hub of crypto interest, blending with ideologies like rationalism, effective altruism, and transhumanism. In the 2010s, these ideas were novel and felt “adjacent to crypto”: many interested in them were also interested in crypto.

Elsewhere, enabling regular businesses to use crypto for payments was a hot topic. In various parts of the world, people accepted Bitcoin—even Japanese waitstaff accepting Bitcoin as tips:

Since then, these communities have undergone many changes. Beyond broader challenges, China experienced multiple crypto crackdowns, pushing Singapore to become a new home for many developers. Silicon Valley split internally: rationalists and AI developers, essentially factions of the same team, diverged into separate camps debating optimism versus pessimism about AI’s default trajectory after Scott Alexander was doxxed by The New York Times in 2020. Ethereum’s regional composition shifted significantly, especially during the 2018 transition to proof-of-stake with entirely new teams, though more through adding new ones than replacing old. Death, birth, and rebirth.

Many other communities deserve mention.

When I first visited Taiwan multiple times in 2016 and 2017, what impressed me most was the combination of self-organizing ability and eagerness to learn from its people. Whenever I wrote documentation or blog posts, I often found that within a day, study groups independently formed, excitedly annotating every paragraph in Google Docs. Recently, members of Taiwan’s Digital Ministry showed equal enthusiasm for Glen Weyl’s ideas on digital democracy and “quadratic voting,” quickly posting a full mind map of the field (including many Ethereum applications) on their Twitter accounts.

Paul Graham once wrote about how each city conveys a message: in New York, “you should earn more money.” In Boston, “you really should read all these books.” In Silicon Valley, “you should be stronger.” When I visited Taipei, the message that came to mind was “you should rediscover the high schooler within you.”

Glen Weyl and Audrey Tang speaking at a study session in Nowhere bookstore, Taipei—four months earlier, I gave a talk there about community notes

In recent years, during multiple visits to Argentina, I’ve been struck by the eagerness and willingness to build and apply the technologies and ideas offered by Ethereum and the broader crypto world. If places like Silicon Valley are the frontier—full of abstract thinking about a better future—then places like Argentina are the front lines, filled with active motivation to tackle today’s urgent challenges: in Argentina’s case, hyperinflation and limited connection to the global financial system. Crypto adoption there is off the charts: I get recognized more often on the streets of Buenos Aires than in San Francisco. And there are many local builders, combining surprising pragmatism and idealism, tackling real-world problems—from crypto/fiat conversion to improving the status of Ethereum nodes in Latin America.

Me and friends at a café in Buenos Aires, paying with ETH

Many others deserve mention: Dubai’s cosmopolitan and highly international crypto community, the growing ZK communities across East and Southeast Asia, Kenya’s vibrant and pragmatic builders, Colorado’s public-goods-oriented solarpunk community, and more.

Finally, Zuzalu in 2023 created a very different, beautiful, fluid subcommunity, poised to thrive independently in the coming years. This is a key part of what draws me to the network state movement: culture and community are not just things to defend and protect—they are things that can be actively created and developed.

6

People learn many lessons while growing up, and different people learn different ones. For me, some of them are:

-

Greed is not the only form of selfishness. Cowardice, laziness, resentment, and many other vices can cause great harm. Moreover, greed itself takes many forms: greed for social status is often as harmful as greed for money or power. As someone who grew up in gentle Canada, this was a major update: I felt taught to believe greed for money and power was the root of most evil, and as long as I ensured I wasn’t greedy for those things (e.g., by repeatedly advocating reducing the ETH supply share of the top 5 “founders”), I fulfilled my duty to be a good person. That’s simply not true.

-

You’re allowed to have preferences without needing a complex scientific justification for why your preferences are objectively, absolutely good. I generally like utilitarianism and often find it unfairly maligned and wrongly equated with cold-heartedness, but here I think excessive utilitarian thinking can sometimes mislead humans: the extent to which you can change your preferences is limited, so if you push too hard, you end up fabricating reasons why everything you like objectively best serves universal human flourishing. This often leads you to unnecessarily argue with others, insisting these awkward claims are correct. A related lesson: someone might not be suitable for you (in any context: work, friendship, etc.), but that doesn’t mean they’re a bad person in any absolute sense.

-

The importance of habits. I intentionally limit many of my daily personal goals. For example, I aim to run 20 km once a month, and otherwise just “do my best.” Because the only effective habit is one you actually maintain. If something is too hard to keep up, you’ll abandon it. As a digital nomad jumping continents and flying dozens of times yearly, any kind of routine is difficult for me, and I must work with this reality. Despite Duolingo’s gamification—pushing you to maintain a “streak” by doing at least something daily—what actually works for me is making positive decisions that reprogram my mind over the long term, setting it to default to different modes.

Everyone learns these long-tail lessons, and in principle I could go on longer. But there’s also a limit to how much one can actually learn from reading others’ experiences. As the world begins changing faster, lessons drawn from others’ narratives become outdated faster. Therefore, to a large extent, simply doing things slowly and gaining personal experience remains irreplaceable.

7

Every good thing in the social world—a community, an ideology, a “scene,” a nation, or even a very small company, a family, or a relationship—is created by people. Even in rare cases where you could write a plausible story about it existing since the dawn of human civilization and the eighteen tribes, at some point, someone actually had to write that story. These things are finite—both as entities themselves, parts of the world, and as your experience of them, a fusion of underlying reality and your own conception and interpretation. As communities, places, scenes, companies, and families disappear, new ones must be created to replace them.

For me, 2023 was a year of watching many big and small things gradually fade into the distance. The world is changing rapidly, the frameworks I’ve used to understand it are shifting, and my role in influencing it is changing too. There is death—a truly inevitable kind of death that will persist even if biological aging and mortality are eradicated from our civilization—but there is also birth and rebirth. Staying active and doing our best to create new things is the task of each of us.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News