RWA vs NWA: Business Value Comparison in the New Era

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

RWA vs NWA: Business Value Comparison in the New Era

The more something claims to be real, the more irrelevant it becomes.

Written by: mattigags, Zee Prime Capital

Translated by: TechFlow

RWA is a well-known concept in the crypto space, short for "real-world assets."

However, mattigags, a researcher from Zee Prime Capital, challenges this notion—what exactly defines “real,” and what makes something “unreal”?

Thus, the author introduces a new concept: NWA (Networks with Attitude), meaning networks imbued with identity or cultural branding—networks capable of generating brand effects without being backed by physical assets. Examples include Bitcoin or Ethereum, as well as various DeFi protocols, memecoins, and consumer-facing applications.

So, in contrast to RWA, do these NWA lack value simply because they aren’t tied to tangible assets? What truly determines whether something has value—the real versus the unreal?

Let’s explore the original insights.

At its inception, the internet didn’t seem real to people. There are many anecdotes from the 1990s to early 2000s—Bill Gates being interviewed by David Letterman, asked “Do you remember radios, tape recorders, magazines?”—and that famous article titled “Why the Web Won’t Be Nirvana.”

Without rich imagination, it's hard to grasp digital technologies before their breakthrough. These things don't appear real, especially when price momentum gets exploited by skeptics, leading us instinctively into debates about what is real and what isn't.

What feels real is often what we're familiar with—things we've seen before, things easier to predict. In uncertain times, our brains seek recognizable patterns to anchor on so-called “fundamentals.” Thus, we end up with a false dichotomy between “real-world assets” (RWA) and “non-real-world assets.”

What does “real” actually mean? Predictable? Tangible? Cash flow? Existing physical assets now tokenized on-chain? To me, it only means cramming old models into new technological paradigms during the aftermath of the last bull market. Because we fear doubling down, we hide behind familiar, outdated frameworks.

I recall an anecdote from the late '90s: people said, “There will be over 1,000 TV channels on the internet.” Today, there are millions—every user potentially a “media company,” giving rise to an entirely new creator economy. This industry is now valued at over $25 billion, with the global online entertainment market reaching $367 billion and expected to surpass $1 trillion by 2028.

Traditional information distribution pipelines could no longer meet demand, and few foresaw this shift. With cryptocurrency, we’re not just unbundling traditional financial rails—we’re also redefining (consumer) products. In this new world where novel user roles emerge constantly, old models no longer apply.

Product-Culture Fit

Walking down Savile Row in London made me reflect on how ready-to-wear fashion faced resistance and skepticism when it emerged in the mid-19th century. The traditional way of acquiring clothing was through tailoring and bespoke fittings, making the idea of “one size fits many” incomprehensible at the time.

Tailors saw the trend as a threat—and rightly so. People questioned the quality of suddenly mass-produced garments, feared technical regression, and doubted innovation. Others worried cheap off-the-rack clothes signaled declining social status.

The fact that ready-to-wear clothes were cheaper and industrially producible sparked a massive cultural transformation. As urban life became busier and faster-paced, convenience grew more appealing. With the rise of mass marketing, status found new pathways into the marketplace.

What’s considered normal today once seemed bizarre; what’s deemed practical was once thought impractical. But this doesn’t mean every oddity becomes normal, or every impractical thing turns useful. It shows that for consumer goods, culture can shift rapidly given the right conditions.

Ready-to-wear brought scalability, enabling the emergence of global fashion brands. A new cultural ecosystem formed around this concept, followed by a massive shift in consumption behavior.

In the 2020s, anything can become a consumer product. People willingly spend money on nonsense, gimmicks, and things they’ll never use. They pay premium prices for sneakers that cost no more than $100 to produce. How does this thin layer of illusion transform a commodity into a luxury?

The entire marketing industry is built on manufacturing illusions. People don’t know different brands share the same products. They have no idea identical clothes are produced in the same factory, merely labeled differently upon shipment. Branding is a reinvention of mass delusion. Yet, no one questions whether brands are “real.”

Brands do generate cash flows. But their existence isn’t based on fundamental physical laws—it’s a social construct rooted in consumer perception, driven by buzzwords and narratives. These brands sell an expectation—how one might feel, look, or be perceived when consuming their products.

So, what fundamentally separates influential tokens or pictures of bored apes from such branded goods? Both sell expectations about identity or experience. Why should one premium be considered more “real” than another? Is it due to the digital-versus-physical divide? Or simply because it’s a new product form?

Are tokens a new form of consumer product, driving a large-scale cultural shift akin to the ready-to-wear revolution of the 19th century?

As digital brand networks, N.W.A. (Networks With Attitude) are rising, turning participants into loyal consumers. Crucially, consumers can also become stakeholders—a highly compelling proposition for the next era of business.

But how do you build a brand around a network? Let’s discuss

N.W.A. (Networks With Attitude)

Bitcoin is often compared to a religion—it starts with code producing a product, then builds an organization willing to buy and promote it. While Bitcoin’s core design and basic properties can be copied or forked, its product and community cannot. Its moat relies on its brand as digital gold.

What are gold’s essential qualities? Scarcity makes it a standardized brand—an effective mass illusion solving a problem. Bitcoin is similar. It also offers superior usability: easier access, tracking, storage, trading, etc.

It’s hard to imagine Bitcoin not eventually becoming a greater brand than gold. All it needs is persistent narrative crafting, reframing, and time. Today, Bitcoin is already a $730 billion global super-brand—but still far from gold’s potential market cap floor of $13 trillion.

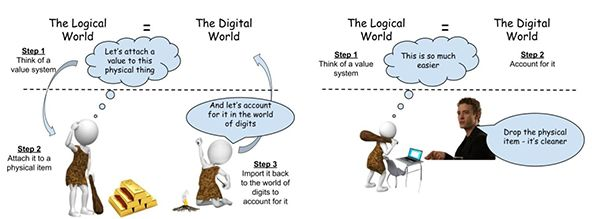

Bitcoin isn’t less real than gold. In fact, Bitcoin may be *more* real than gold, existing purely in the world of 1s and 0s—its entire state visible to all, making coordination easier. This is a useful mass illusion—a societal anchor point for coordination.

Why attach intrinsic value rooted in digital logic to a physical object, then track it digitally again? Gold suffers from poor user experience due to redundant steps. Fundamentally, Bitcoin is better positioned to win this marketing battle.

There are many such NWAs. Take Ethereum, for instance. Contrary to popular belief, Ethereum isn’t necessarily competing with Bitcoin in the long run. While it can serve as a store of value, its greater potential lies as fuel for the world computer. Ethereum is the new internet, where you can directly own things.

Owning Ethereum is a form of conspicuous consumption of blockspace as a Veblen good. Anyone can launch their own NWA on Ethereum (i.e., issue an asset and build a culturally resonant, belief-driven network). These NWAs can be DeFi products, memecoins, or ultimately consumer applications.

Let me repeat: the power of NWAs lies in turning users into stakeholders. Some call this impractical—I’m reminded of how people viewed ready-to-wear fashion. Tokens are increasingly becoming practical anchors within digital culture. They provide strong product-culture fit, enabling new markets to emerge.

Tokens as Products

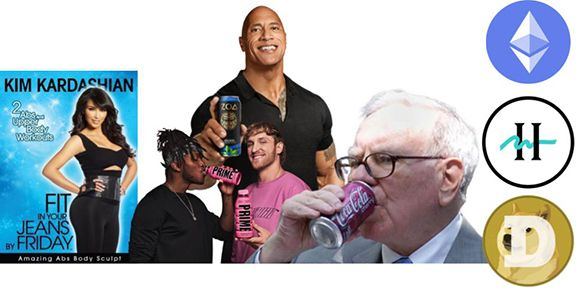

What makes an asset “real”? In finance, the only fundamental is cash flow. Because people are willing to pay for soda (which is mostly net-negative for health), the stocks and valuations of soda companies are considered “real.”

Or are they real because people pour liquid down their throats? Because it’s canned energy (calories)? What could people do without it? All these arguments hold some ground, but the only thing that matters is willingness to spend. That alone sustains it and makes it economically real.

Fiat currency itself isn’t “real”—it’s backed only by consumer trust. Somehow, we’ve agreed that things bought with fiat make it real, while ignoring that reality itself is just symbolic, purchased symbolically.

The truth is, only consumption matters—goods and services—not the medium of exchange. Consumption in a fiat economy is as real as barter. Consumption in a token economy is as real as in a fiat economy. In this sense, crypto is like any good trend: repackaging old ideas into new ones.

Take a random token like Dogecoin. Aside from trading, it basically does nothing. But trading and holding it *is* a form of consumption. Dogecoin is like soda—possibly net-negative for your mental health (as an owner experiencing volatility)—but if someone consumes it, how is it essentially different from soda?

Indeed, Coca-Cola is more “real” than Dogecoin only insofar as its memo is stronger. Coca-Cola has deeper tradition, ubiquitous branding. Some people don’t even know why they order a Coke. But without it, they’d drink something else—life wouldn’t change much.

On the internet, users become “TV channels.” With crypto, “Coca-Cola stock” and soda become one product.

Digitalization leads to hyper-monetization and hyper-financialization. As we livestream mass delusions, the world becomes a reality show. This is the true metaverse—a 24/7 casino where human suffering—war, GDP, inflation—becomes spectacle.

Serious political issues become entertainment; entertainment becomes politicized. This happens when information dissemination costs approach zero, and monetization depends on people extracting dopamine from screens. Noise is priced as signal because noise has become the product.

With crypto, we double down. Now everyone can be a media channel, everyone a stakeholder in specific products. The thrill of watching numbers go up becomes a product, a new addiction. Tokenization is the path of least resistance to more dopamine.

Numbers in the digital world become more important than the physical goods they represent. This mirrors Bitcoin vs. gold. Bitcoin wins because it’s native to the digital realm. Dopamine production, distribution, and consumption are cheaper in the bit world.

This aligns with the theory: “Culture is the product, everything else is auxiliary.” Networks With Attitude are tokenized culture—a mechanism for continuously flipping consumer preferences. Perhaps, someday, cash flows will follow.

Earlier I used Dogecoin as an example—an archetypal token showing function rather than optimal design. Like most products, many are gimmicks with little real utility. But fundamentally, value depends entirely on consumer perception.

Utility is Futile, Liquidity is the Future

In an information-rich world, credibility is the scarcest resource. Thanks to blockchain, tokens will become machines of credibility. They will be sources of provenance and authenticity, origins of belonging, platforms for creating new brands and narratives. Without credible authenticity, there can be no brand.

Culture will realign around tokens because tokens are superior tools for value creation, transfer, and signaling. For a world where most communication happens digitally, this is a better standard. Tokens enable direct, authentic cultural ownership. This isn’t just “entertainment until death.”

People are experimenting with token-based fan and loyalty models. Ultimately, we’re discussing the transition from UGC (User-Generated Content) to UGP (User-Generated Profit). Cases like VitaDAO and HairDAO exemplify goal-aligned communities powered by tokens—with many more to come.

Tokenization of the world won’t happen top-down, but bottom-up. It won’t start with tokenized treasuries and real estate. It begins with cultural shifts—people using tokens for commerce and finance, forming tribes engaged in production, marketing, consumption, and self-exploitation online.

Now imagine David Letterman asking, “Do you remember LLCs?”

Of course. But does that mean there couldn’t be a better way to create micro-economic units in a rapidly digitizing society? Do old models still make sense? If we can now build networks with digital-native integrity, why wouldn’t we? Isn’t that a better approach? Why not use tokens?

Here comes Letterman again: “Remember the dollar?”

Of course, but stablecoins let you do more. The explosion of stablecoins is driven by consumer preference, not governments printing dollars on-chain.

Things on the internet want to move freely, yet naturally form tokenized boundaries. Tokens will open markets for culture. Tokens bring liquidity to places unseen, enabling seamless network experiences and creating new user roles. Liquidity bootstrapping pools become culture bootstrapping pools.

Tokens are products of “Networks With Attitude”—they are new-world assets, digital brands, and novel business forms. Real-world assets aren’t as important as we currently believe. Stablecoins prove this—they’re bridges from the real world into the new world.

The more something claims to be “real,” the more irrelevant it becomes. Tokens represent a bottom-up commercial revolution, not a top-down financial reform.

Thanks to long_solitude, Shaun, Xen, Mable, and Luffistotle for valuable feedback.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News