RWA Asset Tokenization Future Blueprint Report: Comprehensive Analysis of Underlying Logic and Pathways to Mass Adoption

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

RWA Asset Tokenization Future Blueprint Report: Comprehensive Analysis of Underlying Logic and Pathways to Mass Adoption

On-chain fiat currency opens a brand-new door for the promotion of tokenization technology in real-world applications.

Authors: Bocaibocai, Head of Research of Ample FinTech; Annabella, CMO of zCloak Network

Word count: This report exceeds 28,000 characters and covers a broad scope—please read patiently.

In 2023, the most prominent topic in the blockchain space has undoubtedly been Real World Asset Tokenization (RWA). This concept has not only sparked intense discussion within the Web3 community but has also attracted significant attention from traditional financial institutions and government regulators worldwide, who view it as a strategically important direction. For instance, authoritative financial institutions such as Citibank, JPMorgan Chase, and Boston Consulting Group have each released their own tokenization research reports and are actively advancing pilot projects.

Meanwhile, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority explicitly stated in its 2023 annual report that tokenization will play a key role in Hong Kong’s financial future. Additionally, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, Japan’s Financial Services Agency, JPMorgan, DBS Bank, and other financial giants have jointly launched an initiative called "Project Guardian" to deeply explore the vast potential of asset tokenization.

Despite the growing popularity of RWA, according to our observation, there is significant divergence within the industry regarding the understanding of RWA, and debates over its feasibility and prospects remain contentious.

-

On one hand, some argue that RWA is merely market hype and cannot withstand rigorous scrutiny;

-

On the other hand, others remain highly confident about RWA and optimistic about its future.

At the same time, articles analyzing different perspectives on RWA have emerged rapidly.

The authors aim to share their perspective on RWA through this article, offering deeper exploration and analysis of its current state and future trajectory.

Due to personal limitations in understanding, all content in this article reflects individual opinions. Feedback and discussion are welcome.

Key Takeaways:

-

Crypto's RWA logic primarily revolves around transferring the yield rights of income-generating assets (such as U.S. Treasuries, fixed income, stocks) onto the chain, enabling off-chain assets to be used as collateral for loans to obtain liquidity of on-chain assets, and bringing various real-world assets (like sand, minerals, real estate, gold) onto the chain for trading, reflecting a one-sided demand from the crypto world toward real-world assets, with many compliance obstacles.

-

The future development of Real World Asset Tokenization (RWA) will be a new financial system built on permissioned chains by traditional financial institutions, regulatory bodies, and central banks using DeFi technology. Achieving this requires integration of computational systems (blockchain technology), non-computational systems (e.g., legal frameworks), on-chain identity systems with privacy protection, on-chain fiat currencies (CBDCs, tokenized deposits, regulated stablecoins), and robust infrastructure (low-barrier wallets, oracles, cross-chain protocols, etc.).

-

Blockchain is the first effective technical means supporting digital contracts after the development of computers and networks. Therefore, blockchain can essentially be seen as a platform for digital contracts, where contracts are the fundamental representation of assets, and tokens serve as the digital carriers of assets after contract formation—making blockchain the ideal infrastructure for digital or tokenized asset expression.

-

As a distributed system maintained collectively by multiple parties, blockchain supports creation, verification, storage, transfer, execution, and other operations of digital contracts, solving the problem of trust transmission. As a "computational system," blockchain satisfies humanity's need for reproducible processes and verifiable outcomes. Thus, DeFi becomes a "computational" innovation in finance, replacing the computational aspects of financial activities, achieving cost reduction, efficiency gains, and programmability via automated execution, while still unable to replace the "non-computational" aspects based on human cognition—hence, credit-based unsecured lending remains unrealized in current DeFi due to the lack of relational identity systems and legal protections.

-

For traditional finance, Real World Asset Tokenization enables digital representations of real-world assets (stocks, derivatives, currencies, rights, etc.) on blockchains, extending the benefits of distributed ledger technology across diverse asset classes for exchange and settlement.

-

Financial institutions enhance efficiency by adopting DeFi technologies, using smart contracts to automate traditionally manual, rule-based financial operations, enhancing programmability. This reduces labor costs and unlocks new possibilities, especially innovative financing solutions for SMEs, opening up transformative potential in the financial system.

-

With increasing recognition and adoption of blockchain and tokenization by traditional financial sectors and governments globally, alongside rapid improvements in blockchain infrastructure, blockchain is moving toward integration with traditional architectures, addressing real-world pain points with practical solutions rather than remaining isolated in a parallel “digital world” disconnected from reality.

-

In a future landscape of multiple jurisdiction-specific permissioned chains, cross-chain technology will be crucial for resolving interoperability and fragmented liquidity issues. Protocols like CCIP could connect tokenized assets across any blockchain, enabling universal interconnectivity among chains.

-

Currently, numerous countries are actively advancing legal and regulatory frameworks related to blockchain. Meanwhile, blockchain infrastructure—including wallets, cross-chain protocols, oracles, middleware—is rapidly maturing. CBDCs are being implemented, new token standards capable of representing complex assets (e.g., ERC-3525) are emerging, and privacy-preserving technologies—especially zero-knowledge proofs—are advancing, along with increasingly mature on-chain identity systems. We appear to be on the cusp of large-scale blockchain adoption.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction to Asset Tokenization Background

- RWA from the Crypto Perspective

- RWA from the TradFi Perspective

II. From Blockchain First Principles: What Problems Does Blockchain Solve?

- Blockchain as Ideal Infrastructure for Asset Tokenization

- Blockchain Meets Humanity's Demand for "Computational" Systems

- DeFi as "Computational" Innovation in Finance

III. Asset Tokenization: Transformative Impact on Traditional Finance

- Establishing Trusted Global Payment Platforms, Reducing Costs and Improving Efficiency

- Programmability and Transparency

IV. What Is Needed for Mass Adoption of Asset Tokenization?

- Robust Legal Frameworks and Permissioned Chains

- Identity Systems and Privacy Protection

- On-chain Fiat Currency

· Oracles and Cross-chain Protocols

· Low-barrier Wallets

V. Outlook on the Future

I. Introduction to Asset Tokenization Background

Asset tokenization refers to the process of representing assets as tokens on programmable blockchain platforms. Typically, tokenizable assets fall into two categories: tangible assets (real estate, collectibles, etc.) and intangible assets (financial instruments, carbon credits, etc.). Transferring assets recorded on traditional ledgers to a shared, programmable ledger platform [1] represents a disruptive innovation for traditional finance—one that may reshape humanity’s future financial and monetary systems.

First, we highlight an observed phenomenon: “There are two fundamentally different groups with opposing views on RWA asset tokenization.” We categorize them as Crypto RWA and TradFi RWA—the focus of this article being the latter.

- RWA from the Crypto Perspective

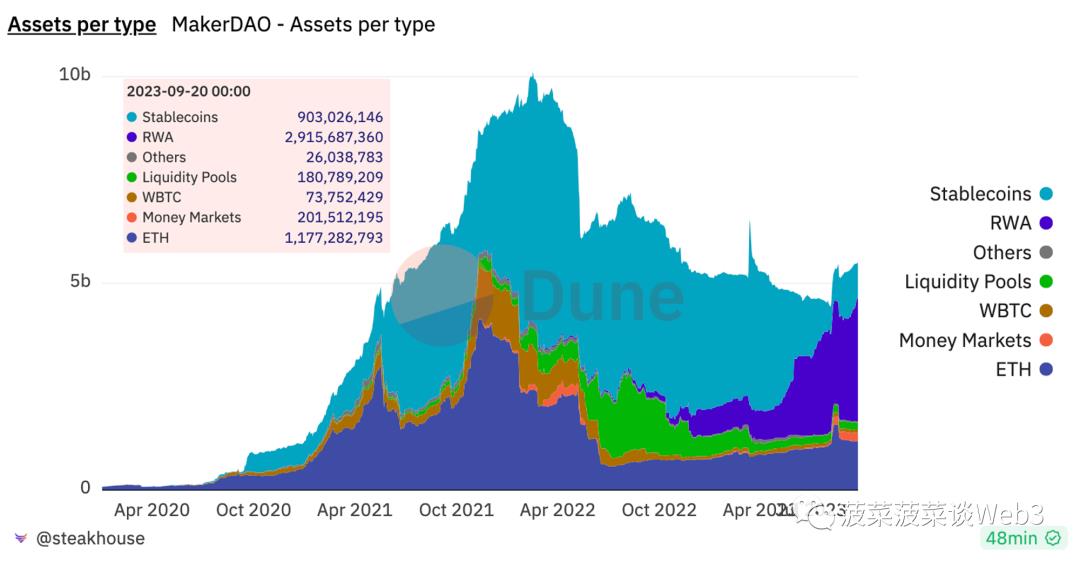

Let’s begin with Crypto RWA: We define Crypto RWA as the crypto world’s unilateral demand for yields from real-world financial assets. The main backdrop is the Federal Reserve’s continuous interest rate hikes and balance sheet contraction, which significantly impact risk asset valuations and drain liquidity from the crypto market, causing DeFi yields to decline steadily. Against this backdrop, U.S. Treasury bonds offering ~5% risk-free returns became highly attractive in the crypto space. The most notable example was MakerDAO’s aggressive purchase of U.S. Treasuries this year. As of September 20, 2023, MakerDAO had acquired over $2.9 billion in real-world assets including U.S. Treasuries.

Data source: https://dune.com/steakhouse/makerdao

MakerDAO’s purchase of U.S. Treasuries allows DAI to diversify its backing assets by leveraging external credit, stabilize its exchange rate through long-term additional yield from U.S. Treasuries, increase issuance flexibility, and reduce reliance on USDC, mitigating single-point risks [2]. Moreover, since U.S. Treasury income flows entirely into MakerDAO’s treasury, the protocol recently boosted DAI’s interest rate to 8% by sharing part of these yields, increasing demand for DAI [3].

MakerDAO’s strategy is clearly not replicable by all projects. With MRK token prices surging and market enthusiasm for the RWA narrative rising, besides larger, compliant RWA-focused public chain projects, numerous RWA concept ventures have sprung up, attempting to tokenize every imaginable real-world asset on blockchain, including some absurd ones, leading to a chaotic and mixed-quality RWA ecosystem.

From our perspective, Crypto RWA centers on transferring yield rights of income-generating assets (U.S. Treasuries, fixed income, stocks, etc.) onto the chain, using off-chain assets as collateral to borrow and gain liquidity for on-chain assets, or tokenizing various real-world assets (sand, minerals, real estate, gold) for trading.

Thus, Crypto RWA reflects a one-sided demand from the crypto world toward real-world assets—a model fraught with compliance challenges. MakerDAO’s approach involves compliant on/off-ramps (via Coinbase, Circle) and legally purchasing U.S. Treasuries to capture yield—not selling those yields directly on-chain. Notably, what exists on-chain isn’t U.S. Treasuries themselves but their yield rights, and converting Treasury-generated fiat income into on-chain assets adds operational complexity and friction costs.

The rapid rise of the RWA narrative owes much to more than just MakerDAO. In fact, Citibank’s report titled “Money, Tokens, and Games” stirred strong reactions in the industry. This report revealed deep interest from traditional financial institutions in RWA and fueled speculative excitement, amplifying expectations and hype as rumors spread about major institutions entering the space.

- RWA from the TradFi Perspective

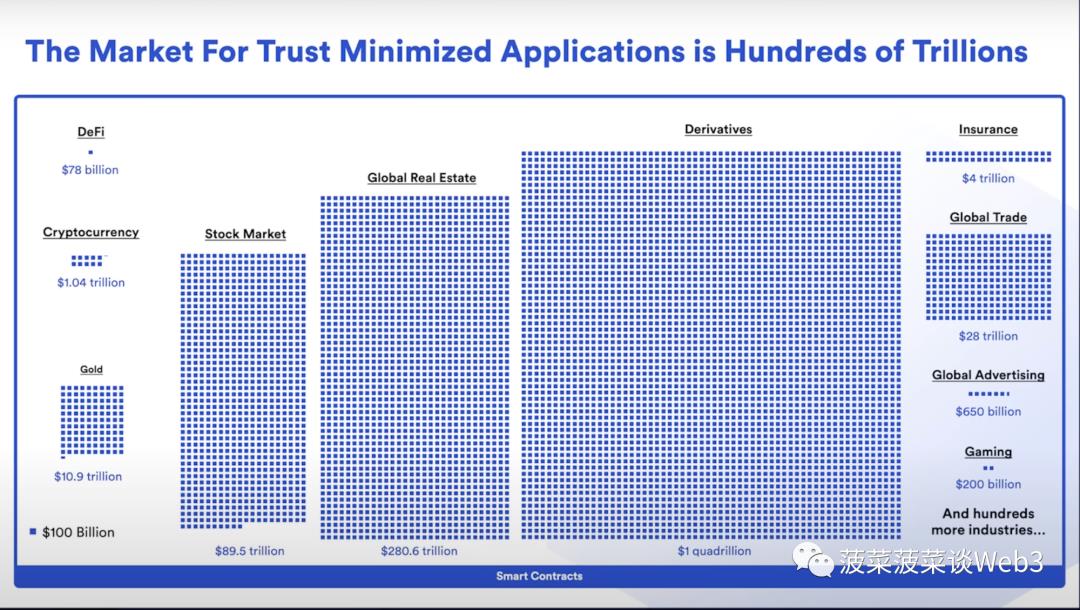

If viewed from the Crypto lens, RWA expresses the crypto world’s one-way desire for traditional financial asset yields. But from the traditional finance (TradFi) standpoint, crypto’s capital size pales compared to multi-trillion-dollar traditional markets. Whether U.S. Treasuries or other financial assets, adding another blockchain-based sales channel seems unnecessary. The visual comparison below highlights the scale disparity between crypto and traditional financial markets.

Therefore, from the TradFi perspective, RWA represents a mutual embrace between traditional finance and decentralized finance (DeFi). For the traditional financial world, DeFi services powered by smart contracts represent an innovative fintech tool. TradFi’s RWA focuses on integrating DeFi technology to enable asset tokenization, empowering the traditional financial system to reduce costs, improve efficiency, and address existing pain points. The emphasis lies on the benefits tokenization brings to traditional finance—not simply finding a new distribution channel for assets.

We believe distinguishing between these two logics is essential, as they differ profoundly in underlying principles and implementation paths. First, their choice of blockchain type diverges. Traditional finance RWA follows a permissioned chain path, while crypto-world RWA relies on public chains.

Public chains, characterized by open access, decentralization, and anonymity, pose substantial compliance hurdles for project teams. Users lack legal recourse when facing rug pulls or similar incidents. Coupled with rampant hacking and high security awareness requirements, public chains may not be suitable for widespread issuance and trading of real-world assets.

Permissioned chains used in TradFi RWA provide basic prerequisites for legal compliance across jurisdictions. On-chain KYC establishing identity systems is a necessary condition for RWA. Under legal safeguards, institutions holding assets can issue and trade tokenized assets compliantly. Unlike Crypto RWA, assets issued on permissioned chains can be natively on-chain rather than mere mappings of existing off-chain assets. This native on-chain financial asset RWA holds immense transformative potential.

To summarize our core argument: we believe the future of Real World Asset Tokenization (RWA) will be a new financial system built on permissioned chains, driven by traditional financial institutions, regulators, and central banks using DeFi technology. To realize this system, we require computational systems (blockchain technology), non-computational systems (legal frameworks), on-chain identity systems (DID, VC), on-chain fiat currencies (CBDCs, tokenized deposits, regulated stablecoins), and comprehensive infrastructure (low-barrier wallets, oracles, cross-chain tech, etc.).

The following sections will delve into each component mentioned above, starting from blockchain’s first principles, explaining mechanisms in detail and providing real-world case studies to support our arguments.

II. From Blockchain First Principles: What Problems Does Blockchain Solve?

- Blockchain as Ideal Infrastructure for Asset Tokenization

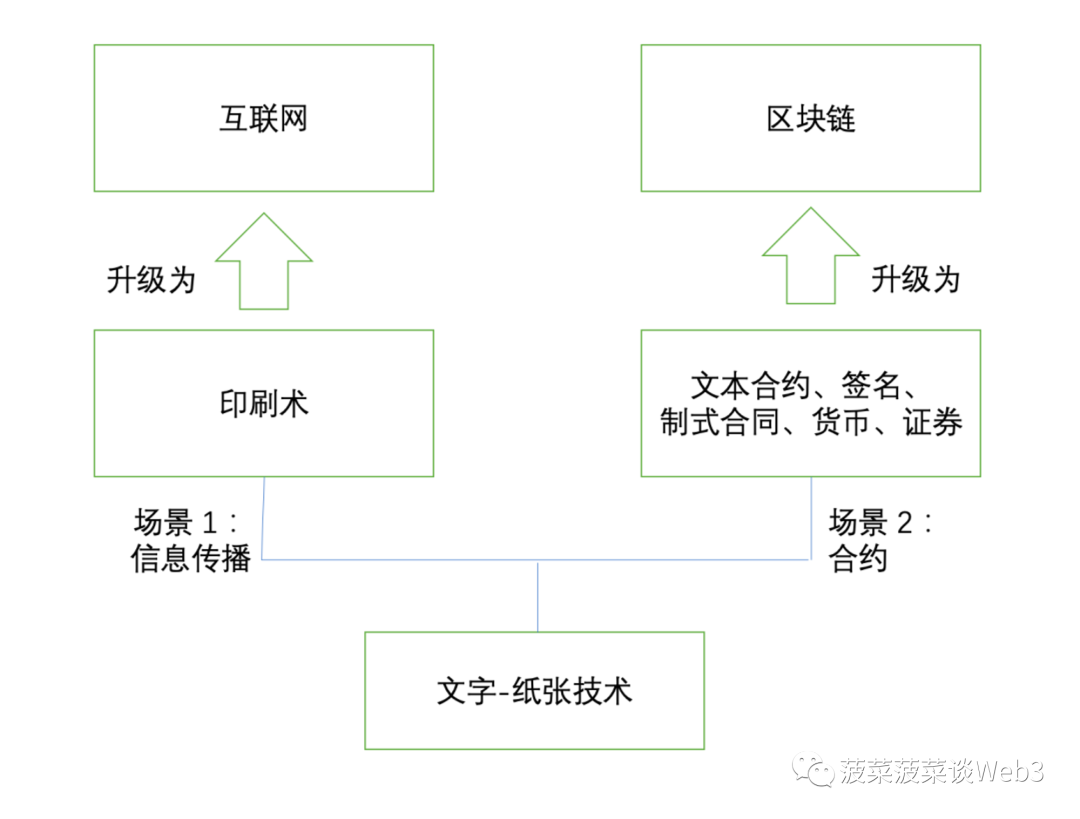

Before exploring blockchain’s first principles, we must clarify its essence. Mr. Meng Yan’s article “What Are Digital Assets?” [4] offers a comprehensive analysis of blockchain’s nature and digital assets, stating: **“Text and paper are considered among humanity’s most important inventions, immeasurably advancing civilization—possibly surpassing the cumulative impact of all other technologies.”** These technologies mainly serve two domains: information dissemination and supporting contracts/instructions.

In the domain of information dissemination, text enables low-cost copying, editing, and sharing of knowledge and information, promoting widespread knowledge transfer and idea diffusion. In the domain of supporting contracts/instructions, text records and conveys various directives—such as ancient emperors sending military orders via documents, bureaucracies transmitting instructions, or commercial agreements formalized in written contracts, forming consensus or even legal statutes, preserving evidence for future oversight and arbitration.

These two application areas differ significantly. In information dissemination, people prioritize low-cost, lossless copying and ease of editing; whereas in contract/instruction transmission, authenticity, non-repudiation, and immutability are paramount. To meet these needs, humans developed sophisticated anti-counterfeiting printing techniques and still widely use handwritten signatures and other verification methods to ensure reliability.

When the internet ushered humanity into the digital age, it greatly fulfilled the demands of information dissemination. The internet enables fast, low-cost, lossless, and convenient information transmission, unlocking unprecedented possibilities for global knowledge and information sharing. Information sharing has become faster and simpler than ever before—academic knowledge and daily updates can now be instantly disseminated worldwide, significantly advancing human society.

However, the internet struggles with handling contract/instruction systems, particularly in contexts requiring authority and trustworthiness—such as corporate operations, government decisions, and military commands—where information credibility becomes critical. In such scenarios, relying solely on internet-transmitted information may lead to serious risks and losses due to insufficient credibility. This stems from the internet’s primary design focus on the first application scenario—rapid, extensive, and convenient information delivery—often neglecting information authenticity and accuracy.

Under these circumstances, people attempted to compensate via centralized decision-making and trusted third parties, making this the dominant method for achieving credible information transmission. However, centralized power structures lead to concentration and abuse of power, rendering information transmission opaque and unfair. Introducing third parties introduces further security vulnerabilities and trust crises, as these intermediaries themselves may become unreliable sources.

Thus, blockchain technology emerged as a novel solution for handling contract and instruction systems. Blockchain, as a decentralized, transparent, and immutable distributed ledger, ensures information authenticity and reliability—eliminating the need to rely on centralized institutions or third parties for trust establishment. This innovative technology offers fresh perspectives and solutions for information transmission problems in contract and instruction systems, guaranteeing authenticity, integrity, and consistency without requiring centralized validation.

If the internet represents a digital upgrade of text-paper technology in information dissemination, then blockchain is undoubtedly its digital evolution in supporting contracts/instructions. Therefore, we can narrowly define blockchain as a distributed system collectively maintained by multiple parties, supporting creation, verification, storage, transfer, execution, and other operations of digital contracts. Indeed, blockchain is the first effective technological means supporting digital contracts after the development of computers and networks. Hence, since blockchain is fundamentally a platform for digital contracts—and contracts are the basic form of assets[4]—tokens are the digital carriers of assets formed after contracts are established, making blockchain the ideal infrastructure for digital or tokenized asset expression.

Image source: https://www.defidaonews.com/article/653729

- Blockchain Satisfies Humanity’s Need for “Computation”

Blockchain provides infrastructure for asset tokenization, and smart contracts represent the most basic form of digital assets. Ethereum’s Turing completeness allows smart contracts to express various asset types, giving rise to token standards such as fungible tokens (FT), non-fungible tokens (NFT), semi-fungible tokens (SFT), etc.

One might ask: why can only blockchain achieve digital asset representation? Because blockchain solves the “computational” problem—ensuring “reproducible processes and verifiable results”—under conditions preventing manipulation. We consider “reproducible processes and verifiable results” as blockchain’s first principle, since blockchain operates precisely on this basis: after one node records a transaction, many others re-execute the recording process (process reproducibility); if declared results match independently verified results, it becomes an “established fact” permanently recorded in the blockchain world [5].

When examining what problems blockchain can solve, dividing issues into “computational systems” and “non-computational systems” helps us see more clearly. Blockchain addresses problems within “computational systems”—those based on “reproducible processes and verifiable results.” “Non-computational systems,” however, involve matters that cannot achieve “reproducible processes and verifiable results,” such as those influenced by human cognition. After all, if human cognition, thinking, and judgment were perfectly “reproducible and verifiable,” wouldn’t humans become robots reacting identically to identical stimuli?

Throughout history, humans have consistently demanded “reproducible processes and verifiable results.” Due to limited technological development, humans resorted to physical and cognitive simulations of this “computational” process—using stones for counting or knotting ropes for record-keeping as primitive tools. Ancient Chinese invented counting rods and abacuses to meet growing computational demands. But since humans make mistakes, they couldn’t effectively achieve “reproducible processes and verifiable results.” With the advent of computers, this process could be solidified in software programs. Continuous upgrades of tools satisfying “computational” needs drove qualitative leaps in productivity, becoming a vital force propelling scientific, technological, and societal advancement.

However, in centralized “computational systems” like the internet, when human subjectivity interferes with the system, “reproducible processes and verifiable results” fail. Hackers altering programs to produce different outputs compromise information reliability and authenticity, hindering trust transmission and construction.

With blockchain’s emergence, a new tool satisfying “computational” demands arose: once blockchain achieves decentralization, human subjectivity finds it harder to interfere with the computational system. For example, to alter a smart contract’s output, hackers would likely need to control over 50% of the network’s nodes—an attack usually disproportionate in cost versus benefit. Thus, under normal conditions, blockchain effectively meets humanity’s demand for “computation.”

- DeFi as “Computational” Innovation in Finance

Since Ethereum and smart contracts emerged, blockchain has occupied a pivotal position in finance due to its inherent financial attributes, making finance one of its primary application areas. Thus, decentralized finance (DeFi) naturally evolved as the most widespread blockchain application.

DeFi is a new financial model relying on distributed ledger technology to offer financial services—lending, investing, or exchanging crypto assets—without depending on traditional centralized financial institutions. DeFi protocols implement these services via smart contracts—programs automating traditional financial logic. DeFi users don’t interact directly with counterparties but with programs aggregating other users’ assets, maintaining control over their funds [6].

Viewing blockchain as a “computational system,” we can regard DeFi—a financial system composed of smart contracts—as a “computational” innovation in finance. Smart contracts replace “computational” elements in traditional finance—steps in financial activities relying on humans or machines to “obtain deterministic results through repeated processes,” such as clearing, settlement, transfers, and repetitive tasks not dependent on human cognition. In short, DeFi enables smart contracts to fully execute time-consuming, manual steps in traditional finance, significantly reducing transaction costs, eliminating settlement delays, and enabling automation and programmability.

The counterpart to “computational systems” is “non-computational systems”—i.e., human cognition. Blockchain is purely computational—it solves computational problems but not cognitive ones. In finance, the cognitive system corresponds to the credit system—credit assessment and risk control in lending. Despite identical income and bank statements, different banks may assign varying credit limits.

For example, one customer might receive a $10,000 credit limit at one bank and $20,000 at another. Such differences aren’t based on repeatable, verifiable computational processes but stem deeply from human cognition, experience, and subjective judgment. Each bank has its risk control system, yet final credit decisions hinge decisively on human factors. These cognitive decisions possess irreproducibility and incompletely verifiability—they blend subjectivity and interpretation of gray-area issues.

Or take debt relationships: can putting debt contracts on-chain and automating repayments solve defaulting? To answer, we must first dissect debt itself. Debt isn’t merely a contract or form—it’s a relationship built on mutual recognition and trust between people. Fundamentally, establishing debt relationships depends less on contract formation and more on human cognition.

Blockchain technology can place the “entity” of a debt contract on-chain, setting rules via programming to automate repayment and debt transfer. This process is predictable and verifiable because it relies on fixed rules ensuring “process repeatability and result verifiability.” Yet, this system doesn’t engage the cognitive level.

While the “entity” of a debt contract is objectively confirmed and secured technically, the formation, modification, or termination of debt relationships rests on human cognition. Such cognition cannot be programmed or placed on-chain. Human cognition isn’t a “repeatable, verifiable” process—it changes with environment, emotions, and information. When a debtor’s cognition shifts, they may choose not to fulfill obligations—defaulting. Hence, on-chain solutions cannot resolve defaults, as this is a cognitive issue, not a computational one.

Some may ask: doesn’t DeFi lending protocols use smart contract liquidations to handle borrower defaults? Isn’t DeFi lending a form of credit? Jake Chervinsky, General Counsel at Compound, published an article arguing: “DeFi lending protocols don’t actually involve lending—they’re interest rate agreements.”[7] Simply put, DeFi lending generates no actual credit. Most DeFi lending protocols operate on the same basic mechanism: over-collateralization and liquidation. Borrowers must deposit collateral exceeding the loan amount—for example, pledging $100 worth of ETH to borrow $65 in USDT. This is essentially “computational leverage”—no credit is created; borrowers don’t rely on promises of future payments, trust, or reputation.

In summary, blockchain, as a distributed system collectively maintained by multiple parties, supports creation, verification, storage, transfer, execution, and other operations of digital contracts, solving trust transmission. As a “computational system,” blockchain satisfies humanity’s demand for “reproducible processes and verifiable results.” Thus, DeFi becomes a “computational” innovation in finance, replacing the computational components of financial activities, achieving cost reduction and efficiency gains through automated execution while enabling programmability. However, it cannot replace “non-computational” aspects rooted in human cognition. Consequently, current DeFi does not encompass credit—unsecured lending based on credit remains unrealized. This stems from blockchain’s lack of relational identity systems and absence of legal frameworks protecting parties’ rights.

III. How Is Asset Tokenization Disruptive to Traditional Finance?

Financial services are built on trust and enabled by information. This trust relies on financial intermediaries maintaining the integrity of records covering ownership, liabilities, terms, and contracts. These records typically reside in independent systems or ledgers operated separately. Institutions maintain and verify financial data, allowing people to trust its accuracy and completeness.

Because each intermediary holds different pieces of the puzzle, the financial system requires extensive post-hoc reconciliation to settle transactions and ensure consistency across all relevant financial data. This is an extremely complex and time-consuming process. For example, in cross-border transactions, differing regulations and standards across countries, plus involvement of multiple financial institutions and platforms, make this process especially complicated. Settlement cycles often span one to four days, increasing transaction costs and reducing efficiency [8].

As a distributed ledger technology, blockchain shows great potential in addressing widespread inefficiencies in traditional finance. By providing a unified, shared ledger, it directly resolves information fragmentation caused by multiple independent ledgers, greatly enhancing transparency, consistency, and real-time updating capabilities. Smart contract applications further amplify this advantage, encoding transaction terms and conditions to execute automatically when specific criteria are met—significantly improving transaction efficiency, reducing settlement times and costs—especially in complex multi-party or cross-border transactions.

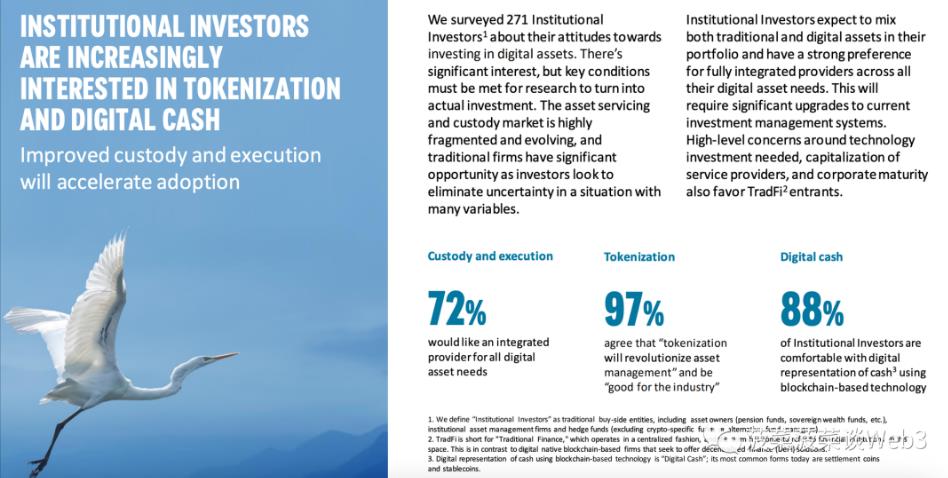

Thus, asset tokenization is increasingly accepted by traditional finance. According to a survey by BNY Mellon, 97% of the 271 financial institutions interviewed believe tokenization will bring a revolutionary transformation to asset management [9], fully demonstrating blockchain’s potential in finance.

Image source:

https://www.bnymellon.com/content/dam/bnymellon/documents/pdf/insights/migration-digital-assets-survey.pdf

Therefore, for traditional finance, Real World Asset Tokenization (RWA) means creating digital representations of real-world assets (stocks, derivatives, currencies, rights, etc.) on blockchain, extending the benefits of distributed ledger technology across diverse asset classes for exchange and settlement.

Financial institutions adopt DeFi technology to further improve efficiency, using smart contracts to replace “computational” segments in traditional finance, automatically executing various financial transactions according to predetermined rules and conditions, enhancing programmability. This not only lowers labor costs but also creates new possibilities for enterprises in specific contexts—particularly innovative financing solutions for SMEs—opening a door full of potential for the financial system.

To deeply explore tokenization’s transformative power in finance, this article presents a more profound analytical framework:

- Establishing Trusted Global Payment Platforms, Reducing Costs and Improving Efficiency

Clearing and settlement permeate human daily life, financial activities, and trade—serving as key mechanisms maintaining economic flow. Though common in everyday life, they often go unnoticed, yet they are the invisible forces ensuring smooth transactions.

In daily shopping, salary payments, splitting bills, etc., clearing and settlement occur constantly. Even splitting dinner costs with friends involves a simplified clearing and settlement process—calculating each person’s share and transferring funds. Similarly, when using Alipay or WeChat Pay, the payment platform undergoes a series of clearing procedures to confirm funds move accurately from your account to the merchant’s. For users, it’s just a simple payment action—but behind the scenes lie complex clearing and settlement workflows (see figure below [10]).

Image source: https://www.woshipm.com/pd/654045.html

According to the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS), clearing systems are defined as a set of arrangements enabling financial institutions to submit and exchange data and documents related to fund or securities transfers. This begins by establishing a “net position” among transaction participants—offsetting mutual debts, known as “netting” [11].

Clearing then refers to the exchange, negotiation, and confirmation of payment instructions or securities transfer instructions—occurring before settlement. Settlement involves the seller transferring securities or other financial instruments to the buyer and the buyer transferring funds to the seller—it’s the final step in the entire transaction. Settlement systems ensure smooth transfer of funds and financial instruments.

Simply put, clearing verifies and prepares transaction details, while settlement executes the actual asset transfer. Let’s illustrate this process with an example:

Clearing (Clearing)

Imagine you and friends dine out and decide to split the bill. Everyone declares their consumption amounts, then collectively calculates how much each should pay. In this scenario:

- Amount Determination: Each friend’s declared consumption amount resembles a payment instruction.

- Communication and Verification: Everyone shares and verifies their amounts—equivalent to sending, receiving, and confirming payment instructions during clearing.

- Total Calculation: After totaling the bill, each person’s payable amount is determined—equivalent to exchanging payment information and confirming the final settlement position (each person’s payable amount).

Thus, clearing is a “verification and preparation” step—parties confirm payable amounts and prepare for the next settlement phase.

Settlement (Settlement)

After everyone knows their share, the next step is actual payment. Each pays their portion, summing to the restaurant’s total. At this point:

- Payment: Each person’s actual payment resembles a funds transfer step.

- Verification: Everyone confirms whether payments were accurate, verifying each member paid correctly—similar to confirming correct funds transfer during settlement.

- Notification: If one friend collects all payments and pays the bill, they notify others once completed—similar to post-settlement notification procedures.

Thus, settlement refers to actual funds flowing from one party to another, confirming transaction completion.

Clearly, in traditional finance, clearing and settlement constitute a “computational” accounting and confirmation process. Parties reach consensus through constant verification and validation, then proceed with asset transfer. This requires collaboration among multiple financial departments and incurs high labor costs, along with risks of operational errors and credit exposure.

On June 28, 1974, a notorious bank collapse drew global financial attention—the demise of Herstatt Bank exposed cross-border payment credit risks and their potentially devastating impacts. That day, several German banks conducted Deutsche Mark-to-U.S. dollar foreign exchange trades, intending to send dollars to New York, with Herstatt Bank as the counterparty.

However, due to time zone differences between Germany and the U.S., the clearing process faced significant delays. This time gap caused dollars not to be transferred immediately to counterpart banks, instead “lingering” within Herstatt Bank. In short, expected dollar payments didn’t happen as planned. During those critical hours, Herstatt Bank received a winding-up order from German authorities.

Due to insufficient payment capacity, it failed to transfer corresponding dollar funds to New York, ultimately collapsing. This sudden bankruptcy sent shockwaves, causing varying degrees of losses to multiple German and American banks involved in forex trading. This incident promoted wider adoption of real-time gross settlement systems in cross-border payments and led to the establishment of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision [12], highlighting the importance of clearing and settlement in international financial markets.

Leveraging its distributed ledger properties, data immutability, and traceability, blockchain enables atomic settlement through smart contracts, where when one party pays an asset, the other simultaneously receives the corresponding asset—eliminating settlement risks and costs while enabling real-time settlement and dramatically boosting transaction efficiency.

By integrating blockchain into cross-border payment settlements, we uncover its profound significance: it builds an efficient peer-to-peer payment network, alleviating the prolonged clearing times typical of traditional cross-border payment methods. By removing third-party intermediaries, it enables 24/7 payments, instant receipts, easy withdrawals, and seamlessly meets the convenience demands of cross-border e-commerce payment settlements. Furthermore, it establishes a low-cost, globally integrated cross-border payment trust platform, reducing financial risks from cross-border payment fraud [13].

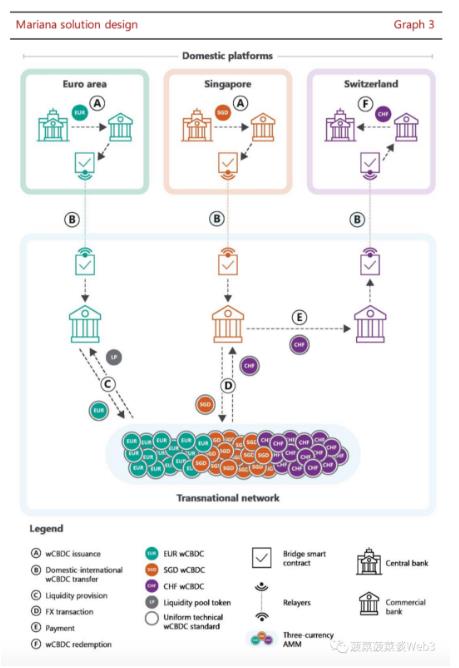

Projeto Mariana—a collaborative effort by the BIS Innovation Hub (BISIH), Banque de France, Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), and Swiss National Bank—released its test report on September 28, 2023. The project successfully validated the technical feasibility of using automated market makers (AMMs) for international cross-border transactions and settlements of tokenized CBDCs [14].

Image source: https://www.bis.org/publ/othp75.htm

Overall, traditional financial payments involve cumbersome clearing and settlement processes, generating extra costs, inefficient due to delayed settlement, and vulnerable to human error, credit risk, and strict time constraints. Blockchain and DeFi technologies offer effective solutions.

Blockchain technology optimizes transaction workflows, eliminates intermediaries, and drastically reduces associated costs. It avoids the lengthy settlement waits of traditional finance, enabling truly 24/7 market operation—especially accelerating speed and accuracy in cross-border payments. More importantly, reduced transaction costs may indirectly boost profits far beyond direct savings, thereby stimulating broader financial market vitality and efficiency.

- Programmability and Transparency

For traditional finance, the programmability and transparency of real-world asset tokenization will bring transformative change—we can illustrate this using financial derivatives as an example. Financial derivatives represent an enormous market in traditional finance, estimated nominal value exceeding hundreds of billions of dollars [15]. This market includes diverse, complex instruments across equities, fixed income, FX, credit, rates, commodities, and more—options (vanilla calls/puts and exotics), warrants, futures, forwards, swaps, etc.

It is precisely the massive potential of financial derivatives’ leverage effect that enables them to create asset scales dozens of times greater than underlying assets. The 2008 financial crisis stands as a classic case of financial derivatives triggering a global disaster. Banks bundled mortgage loans into special financial products—Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)—sold to investors. For banks, this transferred original loan risks, generated cash flow by selling packaged mortgages, and earned interest spreads. Effectively, each loan originated became pure profit—creating immense risk.

The film *The Big Short* vividly illustrates this: when a home loan equals immediate profit and risk is detached from the bank, banks tend to endlessly generate mortgage contracts. Once prime borrowers are exhausted, banks seek subprime individuals to continue the game—even someone with no collateral could get a loan in their dog’s name. These poor-quality “subprime loans”[16] became the fuse for the subsequent financial tsunami.

Amid continuously rising U.S. real estate prices and loose monetary policy with low interest rates, banks kept issuing subprime loans, while Wall Street invented various derivatives—Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs), bundling MBS; synthetic CDOs combining CDOs and Credit Default Swaps (CDS), etc.

Eventually, a proliferation of intricate financial derivatives flooded the market, making it impossible to trace which real assets backed them. Combined with massive subprime loans rated as “low-risk,” distorted ratings meant high-risk assets paid minimal premiums. Layer upon layer, these packaged derivatives were sold to brokers and investors worldwide, causing the entire financial system’s leverage ratio to skyrocket, becoming perilously unstable.

Subsequently, the U.S. raised interest rates, increasing loan interest and causing mass borrower defaults—first visible in the subprime market. But since subprime loans were packaged into ABS, MBS, even CDOs, the problem rapidly spread throughout the financial system. Numerous seemingly high-grade, low-risk derivatives suddenly exposed massive default risks, while investors remained largely unaware of actual risks. Market confidence plummeted, triggering massive sell-offs—a key trigger for the 2008 financial crisis. All this stemmed from chaos, opacity, and excessive complexity in the financial system.

Thus, transparency is crucial for complex financial derivatives. Imagine if tokenization had been adopted before 2008—investors could easily penetrate to underlying assets, perhaps avoiding such a crisis. Moreover, tokenizing derivatives could improve efficiency across multiple stages of securitization—servicing, financing, structuring (tranching) [17].

For example, using semi-fungible token standard ERC-3525 to package assets during securitization—ERC-3525’s digital container feature can bundle non-standard assets into divisible, combinable standardized assets, using smart contracts to tranche (senior/mezzanine/subordinate) and program cash flows—reducing operational and third-party costs, greatly enhancing asset transparency and settlement certainty.

When using blockchain, regulatory monitoring can partly shift to the platform. When key information—seller-submitted documents, historical records, updates—is visible to all key stakeholders on the blockchain platform—single-party governance becomes multi-party governance. Any party can analyze data and detect anomalies—timely disclosure reduces financial market transaction costs [17].

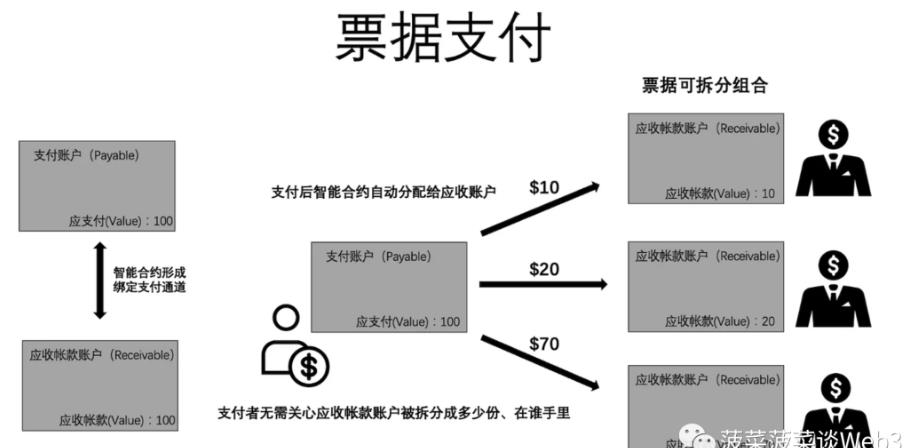

To better understand the benefits of programmability and transparency, Australian startup Unizon’s selection into Australia’s central bank CBDC pilot project—its ERC-3525-based “digital invoice tokenization” initiative—is an excellent case study [18]. In supply chain finance, accounts receivable factoring is a common business model. It allows companies to sell receivables at a discount to third parties (usually factoring firms) to secure financing and improve cash flow.

But due to invoice authentication difficulties, SMEs generally lack sufficient credit support, making investor risk assessment impractical. This leads to widespread SME financing difficulties—if SMEs can’t accept delayed payments, they struggle to win large enterprise orders; but accepting such orders strains working capital, increasing cash flow disruption risks.

By tokenizing invoices, we can add a confirmation step during issuance using private key signatures. Once confirmed, the invoice is generated with both parties’ confirmation signatures—ensuring it’s created in a mutually confirmed state. Considering late payments effectively function as interest-free loans from sellers to buyers, solving invoice authenticity would allow sellers to leverage buyer credit to sell receivables at a discount to factoring institutions for discounted proceeds.

Thanks to ERC-3525’s programmable cash flow capabilities, tokenizing payment invoices in the “digital invoice tokenization” scenario. Create a pair of accounts via ERC-3525: a Payable account and a Receivable account. These accounts form a kind of quantum-entangled, mutually bound payment channel—whenever the buyer sends funds to the Payable account, smart contracts automatically distribute them to the Receivable account. This means regardless of how receivables are split or ultimately held, funds always transfer to the Receivable account per preset ratios—a costly and difficult feat in traditional finance. Using tokenization greatly enhances liquidity, composability, and reduces operating costs in supply chain factoring.

Image source:

https://mirror.xyz/bocaibocai.eth/q3s_DhjFj6DETb5xX1NRirr7St1e2xha6uG9x3V2D-A

In summary, the programmability and transparency of tokenization profoundly impact traditional finance. Transparency provided by blockchain platforms reduces financial risks and information asymmetry in traditional finance, while tokenization’s programmability opens doors to previously impossible operations—greatly reducing manual intervention and third-party involvement. This vastly enhances financial service liquidity and composability, fostering innovation and enabling unprecedented financial product types.

IV. What Is Needed for Mass Adoption of Asset Tokenization?

Tokenization undoubtedly brings revolutionary innovation to traditional finance, but applying this innovation to real-world scenarios still faces many challenges. Below are key factors required for mass adoption of asset tokenization:

- Robust Legal Frameworks and Permissioned Chains

Blockchain, as a purely “computational system,” can only satisfy humanity’s demands for “computational” matters (reduced friction costs, programmability, traceability, etc.), while demands for rights confirmation, judgment, and rights protection require a non-computational system based on cognition—such as robust legal and regulatory frameworks. Legal systems cannot rely on fixed programs; enforcement, adjudication, and risk assessment depend on human cognition. This is precisely what public blockchains fail to deliver. Beyond rampant hacking and frequent security breaches in public chain ecosystems, when a user’s wallet is stolen, assets are nearly unrecoverable and rights unenforceable. Public chains’ openness and anonymity make regulation and law enforcement extremely difficult.

Real-world asset tokenization in traditional finance involves extensive asset issuance and trading operations. For institutions holding core assets, compliance and security are top priorities. Imagine a financial institution issuing hundreds of millions in tokenized financial assets on a public chain, only to have all assets stolen by a North Korean hacker group. In such cases, neither asset recovery nor legal prosecution is possible—clearly unacceptable.

Thus, the financial industry needs a series of legal safeguards to protect investors from fraud and abuse, combat financial crime and cyber offenses, protect investor privacy, ensure participants meet minimum standards, and provide recourse mechanisms when issues arise. Only permissioned chains can simultaneously satisfy “computational” and “non-computational” demands. We can envision each country or region having its own legal and regulatory system, with compliant permissioned chains hosting tokenized real-world assets.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News

Add to FavoritesShare to Social Media