Understanding Rollup Bottlenecks and Optimization Approaches through Performance Differences between opBNB and Ethereum L2

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Understanding Rollup Bottlenecks and Optimization Approaches through Performance Differences between opBNB and Ethereum L2

This article briefly outlines the working principles and commercial significance of opBNB, highlighting BSC's important step toward modular blockchain architecture.

Author: Faust, Geek Web3

Introduction: If there were one keyword to summarize Web3 in 2023, most people might instinctively think of the "Summer of Layer2." While application-layer innovations have emerged one after another, few long-term trends have endured like Layer2. With Celestia successfully popularizing the concept of modular blockchains, Layer2 and modularity have almost become synonymous with infrastructure, making it difficult for monolithic chains to reclaim their former glory. As Coinbase, Bybit, and MetaMask successively launched their own dedicated Layer2 networks, the Layer2 battle has intensified, resembling the fierce competition among new public chains in earlier days.

In this Layer2 war led by exchanges, BNB Chain is naturally unwilling to fall behind. As early as last year, they launched the zkBNB testnet, but due to zkEVM's performance limitations for large-scale applications, opBNB—based on Optimistic Rollup—became a more optimal solution for a general-purpose Layer2. This article aims to briefly explain opBNB’s working principles and its commercial significance, outlining an important step BSC has taken in the era of modular blockchains.

BNB Chain's Path Toward Large Blocks

Like Solana and Heco—public chains supported by exchanges—BNB Smart Chain (BSC), the main chain of BNB Chain, has long pursued high performance. From its launch in 2020, BSC set the gas limit per block at 30 million, with a stable block time of 3 seconds. Under these parameters, BSC achieved an upper TPS limit of over 100 (a mix of various transaction types). In June 2021, BSC raised its block gas limit to 60 million, but in July that year, a blockchain game called CryptoBlades went viral on BSC, generating daily transaction volumes exceeding 8 million, causing fees to spike. This proved that BSC still faced significant efficiency bottlenecks at the time.

(Data source: BscScan)

To address network performance issues, BSC again increased the gas limit per block, eventually stabilizing around 80–85 million. In September 2022, BSC raised the gas limit to 120 million per block, increasing to 140 million by year-end—nearly five times the 2020 level. BSC had previously planned to raise the block gas capacity to 300 million, but likely due to concerns about excessive burden on validator nodes, this proposal for ultra-large blocks was never implemented.

(Data source: YCHARTS)

Later, BNB Chain appeared to shift focus toward modularization/Layer2, no longer obsessing over Layer1 scaling. From zkBNB launched in late 2022 to GreenField in early 2023, this intention became increasingly clear. Driven by strong interest in modular blockchains and Layer2, the author will use opBNB as a case study, revealing from its differences with Ethereum Layer2 the performance bottlenecks inherent in Rollups.

BSC’s High Throughput Boosts opBNB’s DA Layer

As widely known, Celestia outlines four key components of modular blockchains:

-

Execution Layer: The execution environment responsible for running contract code and state transitions;

-

Settlement Layer: Handles fraud proofs or validity proofs and bridges between L2 and L1.

-

Consensus Layer: Reaches agreement on transaction ordering.

-

Data Availability (DA) Layer: Publishes ledger data so validators can download it.

Among these, the DA and consensus layers are often coupled. For example, DA data in optimistic rollups contains a batch of transactions from several L2 blocks. When a full L2 node retrieves this DA data, it already knows the exact order of each transaction. (This is why the Ethereum community considers DA and consensus layers closely related when discussing rollup layering.)

However, for Ethereum Layer2, the DA layer (Ethereum itself) has become the biggest bottleneck limiting Rollup performance, because Ethereum’s current data throughput is too low. Rollups must suppress their own TPS to prevent overwhelming Ethereum with data.

Additionally, low data throughput causes many transactions on Ethereum to remain pending, pushing gas fees to extremely high levels and further increasing the cost of data publication for Layer2. As a result, many Layer2 networks resort to alternative DA layers like Celestia. In contrast, opBNB takes direct advantage of BSC’s high-throughput DA capability to overcome data publishing bottlenecks.

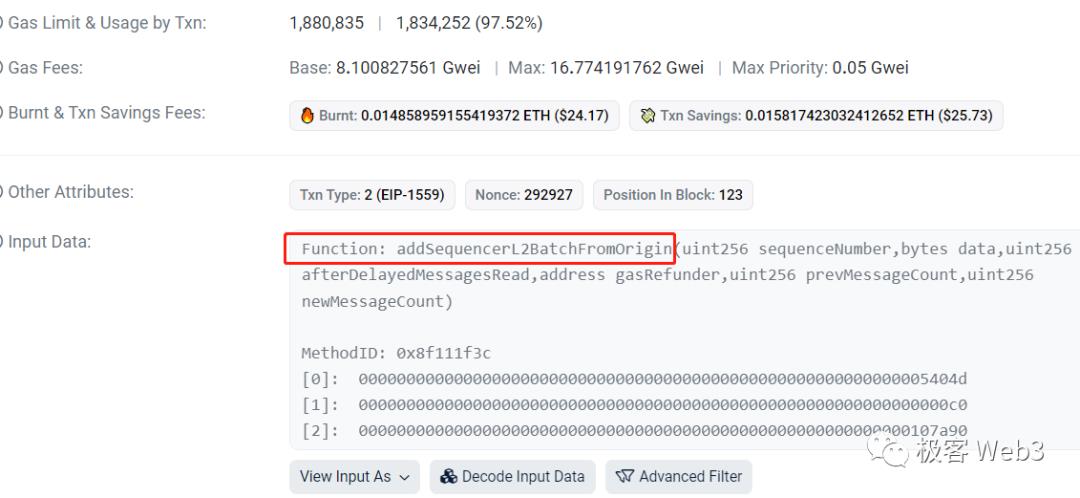

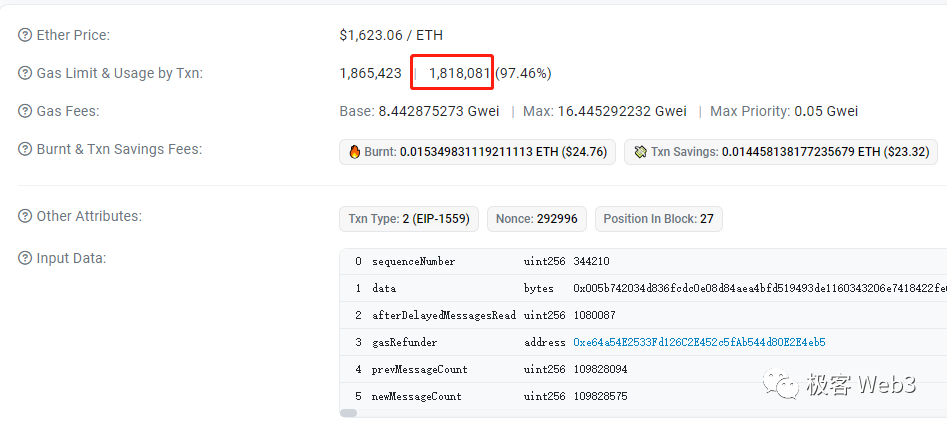

For clarity, let’s briefly review how Rollups publish DA data. Take Arbitrum as an example: an EOA address controlled by the Layer2 sequencer periodically sends a transaction to a designated contract on Ethereum. Within the input parameter calldata, it includes bundled transaction data, triggering corresponding on-chain events and leaving permanent logs in the contract.

Thus, Layer2 transaction data is permanently stored within Ethereum blocks. Anyone capable of running an L2 node can download and parse this data, though Ethereum nodes themselves do not execute these L2 transactions. Clearly, L2 only stores transaction data on Ethereum, incurring storage costs, while computational costs are borne by L2’s own nodes.

The above describes Arbitrum’s DA implementation. Optimism, on the other hand, uses an EOA address controlled by the sequencer to transfer funds to another designated EOA, carrying the latest batch of L2 transaction data in the attached data field. opBNB, built using the OP Stack, follows essentially the same DA data publishing method as Optimism.

Clearly, the DA layer’s throughput limits the size of data Rollups can publish per unit time, thereby capping TPS. Post-EIP1559, each Ethereum block maintains a gas capacity of 30 million, and post-merge, block intervals average ~12 seconds. Thus, Ethereum can process up to 2.5 million gas per second.

Most of the time, each byte in calldata used to store L2 transaction data consumes 16 gas, meaning Ethereum can handle only about 150 KB of calldata per second. In contrast, BSC can process up to approximately 2,910 KB of calldata per second—18.6 times more than Ethereum. The disparity between them as DA layers is evident.

To summarize: Ethereum can carry roughly 150 KB of L2 transaction data per second. Even after EIP-4844 launches, this figure won’t change much—only the DA fee will drop. So, how many transactions can 150 KB per second hold?

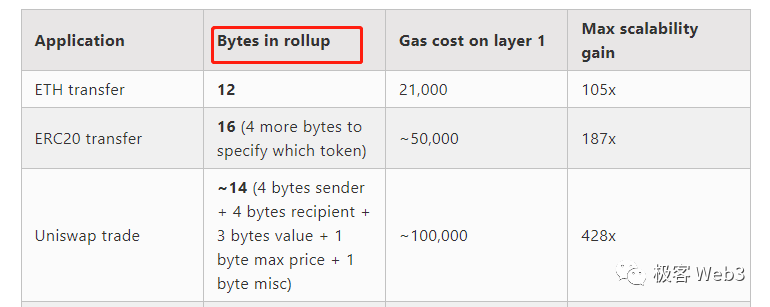

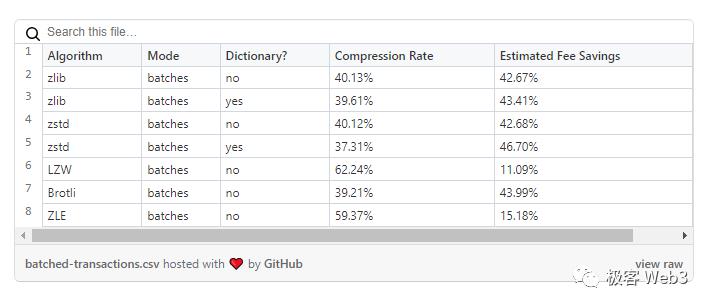

We need to understand Rollup data compression ratios. In 2021, Vitalik overly optimistically estimated that optimistic rollups could compress transaction data down to just 11% of original size. For instance, a basic ETH transfer originally taking 112 bytes could be compressed to 12 bytes; ERC-20 transfers to 16 bytes; Uniswap swaps to 14 bytes. Based on this, Ethereum could theoretically record up to ~10,000 L2 transactions per second (mixed types). However, according to Optimism’s official 2022 disclosure, real-world compression rates reach only about 37%, falling short of Vitalik’s estimate by a factor of 3.5.

(Vitalik’s estimate of Rollup scalability significantly deviates from reality)

(Compression ratios actually achieved by Optimism’s various algorithms)

Therefore, we can reasonably conclude that even at maximum throughput, the combined TPS of all optimistic Rollups on Ethereum cannot exceed 2,000. In other words, if every Ethereum block were fully dedicated to hosting optimistic Rollup data—divided among Arbitrum, Optimism, Base, Boba, etc.—their total TPS would still fall far short of 3,000, even under optimal compression. Moreover, post-EIP1559, each block on average carries only 50% of its maximum gas load, so the actual number should be halved. Even after EIP-4844 launches, although data publishing fees will drop significantly, Ethereum’s maximum block size won’t change much (to preserve mainnet security), so our estimates won’t improve substantially.

According to data from Arbiscan and Etherscan, an Arbitrum batch containing 1,115 transactions consumed 1.81 million gas on Ethereum. Extrapolating from this, if DA layer blocks were completely filled, Arbitrum’s theoretical TPS ceiling would be around 1,500. However, due to Ethereum’s block reorganization risks, Arbitrum cannot publish batches in every Ethereum block, so this figure remains theoretical for now.

Furthermore, once EIP-4337-based smart wallets gain widespread adoption, the DA problem will worsen. With EIP-4337, users can customize identity verification methods—such as uploading biometric data like fingerprints or iris scans—which increases the data footprint of regular transactions. Therefore, Ethereum’s low data throughput remains the primary bottleneck for Rollup efficiency, a problem unlikely to be resolved anytime soon.

On BSC—the main chain of BNB Chain—the maximum calldata size processed per second reaches ~2,910 KB, 18.6 times that of Ethereum. In other words, provided the execution layer keeps pace, the theoretical TPS ceiling for Layer2s within the BNB Chain ecosystem could be around 18 times higher than ARB or OP. This figure is calculated based on BNB Chain’s current max block gas limit of 140 million and 3-second block time.

That is, the aggregate TPS ceiling for all Rollups under BNB Chain is currently 18.6 times that of Ethereum (even including ZKRollups). This helps explain why so many Layer2 projects choose non-Ethereum DA layers—because the difference is obvious.

However, the issue isn't that simple. Beyond data throughput, the stability of the Layer1 itself also impacts Layer2. Most Rollups publish transaction batches to Ethereum only every few minutes, accounting for possible L1 block reorganizations. If an L1 block is reorganized, it affects the L2 ledger. Hence, after publishing a batch, the sequencer waits for several new L1 blocks to be confirmed—significantly reducing rollback probability—before publishing the next batch. This delays finality of L2 blocks and slows confirmation for large transactions (which require irreversible outcomes for security).

In brief, a Layer2 transaction becomes irreversible only after being published into a DA block and after a sufficient number of subsequent DA blocks are created—this is a major constraint on Rollup performance. Ethereum produces a block every 12 seconds. Assuming a Rollup publishes a batch every 15 blocks, there’s a 3-minute gap between batches. Each batch then requires waiting for multiple additional L1 blocks before becoming irreversible (assuming no challenges). Clearly, transactions on Ethereum L2s face long wait times from initiation to finality, resulting in slow settlement. In contrast, BNB Chain produces a block every 3 seconds, achieving irreversibility in just 45 seconds (after 15 new blocks).

Based on current parameters, under equal L2 transaction volume and considering L1 block finality, opBNB can publish transaction data up to 8.53 times more frequently than Arbitrum (every 45 seconds vs. every 6.4 minutes). Clearly, opBNB settles large transactions much faster than Ethereum L2s. Meanwhile, the maximum data size opBNB can publish per batch is 4.66 times larger than Ethereum L2s (with L1 gas limits of 140 million vs. 30 million).

8.53 × 4.66 = 39.74—this represents the current practical TPS gap between opBNB and Arbitrum. (Currently, ARB appears to voluntarily cap its TPS for safety, but theoretically, even if pushed, it would still lag far behind opBNB.)

(Arbitrum’s sequencer publishes a batch every 6–7 minutes)

(opBNB’s sequencer publishes a batch every 1–2 minutes, as fast as every 45 seconds)

Another critical factor is DA layer gas fees. Each time an L2 publishes a transaction batch, there’s a fixed cost unrelated to calldata size: 21,000 gas—a non-trivial expense. If DA layer/L1 fees are high, keeping the fixed cost of publishing batches elevated, the sequencer may reduce publication frequency. Also, when analyzing L2 fees, execution layer costs are negligible; most of the fee is driven by DA costs.

In summary, publishing the same-sized calldata on Ethereum versus BNB Chain consumes identical gas, but Ethereum’s gas price is roughly 10 to dozens of times higher than BNB Chain’s. Translating to user fees, Ethereum Layer2 users currently pay about 10 to dozens of times more than opBNB users. Overall, the difference between opBNB and Ethereum-based optimistic Rollups is significant.

(A 150k-gas transaction on Optimism costs $0.21)

(A 130k-gas transaction on opBNB costs $0.004)

However, increasing DA layer throughput can boost overall Layer2 system throughput, but benefits for individual Rollups remain limited—execution layer processing speed is often insufficient. Even if DA layer constraints are negligible, the execution layer becomes the next bottleneck. If the Layer2 execution layer is slow, overflowed transaction demand spreads to other Layer2s, ultimately fragmenting liquidity. Therefore, improving execution layer performance is crucial—it’s the next hurdle beyond the DA layer.

opBNB’s Execution Layer Advantage: Cache Optimization

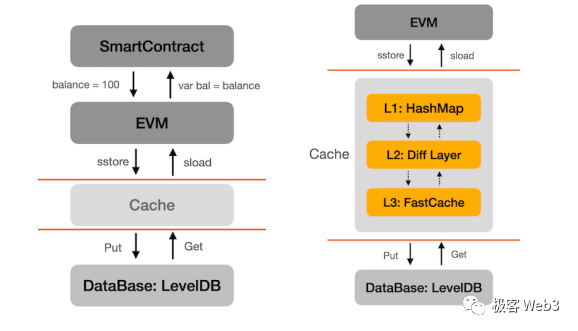

When discussing blockchain execution layer bottlenecks, two common points arise: EVM’s single-threaded sequential execution fails to fully utilize CPU resources, and Ethereum’s Merkle Patricia Trie offers inefficient data lookup—both are critical execution layer constraints. Essentially, scaling the execution layer boils down to better CPU utilization and faster data access. Optimizations targeting EVM’s sequential execution and Merkle Patricia Trees are complex and hard to implement, whereas higher ROI efforts often focus on cache optimization.

Cache optimization revisits classic topics often discussed in traditional Web2 systems and computer science textbooks.

Typically, CPU reads data from memory hundreds of times faster than from disk. For example, retrieving a piece of data may take 0.1 seconds from memory but 10 seconds from disk. Therefore, reducing disk I/O overhead—i.e., cache optimization—is essential for improving blockchain execution performance.

In Ethereum and most public chains, the database storing on-chain address states resides entirely on disk. The so-called World State trie serves merely as an index or directory for this database. Every time EVM executes a contract, it needs relevant address states. If data must be fetched individually from the disk-resident database, transaction execution speed plummets. Hence, introducing caches beyond the database/disk is a necessary acceleration technique.

opBNB directly adopts the cache optimization approach used by BNB Chain. According to information disclosed by opBNB partner NodeReal, early BSC introduced three layers of caching between the EVM and the LevelDB state database, following a design similar to traditional multi-level CPU caches—placing frequently accessed data into faster cache layers so the CPU can retrieve it quickly. With sufficiently high cache hit rates, the CPU relies less on disk, dramatically speeding up execution.

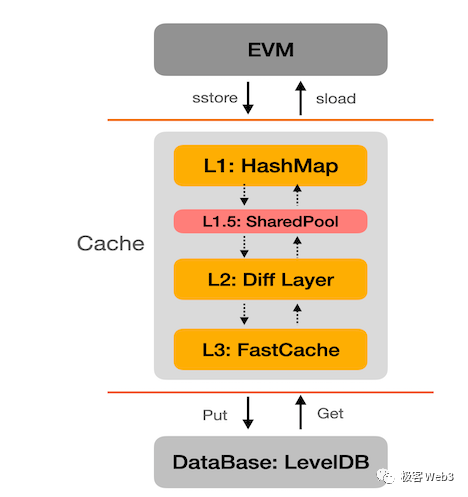

Later, NodeReal added a feature leveraging idle CPU cores not used by EVM to pre-fetch data expected to be needed in upcoming transactions from the database into cache, enabling EVM to access required data directly from cache. This feature is known as “state prefetching.”

The principle behind state prefetching is straightforward: Blockchain nodes have multi-core CPUs, while EVM operates in single-threaded sequential mode, using only one core—leaving others underutilized. These unused cores can help by analyzing the queue of unprocessed transactions to predict which data EVM will need next. Then, they proactively fetch that data from the database into cache, reducing EVM’s data-fetching overhead and accelerating execution.

After thorough cache optimization and paired with adequate hardware, opBNB has effectively pushed node execution performance close to the EVM limit: handling up to 100 million gas per second. One hundred million gas is essentially the performance ceiling for unmodified EVM (based on experimental data from a leading public chain).

To be specific, opBNB can process up to 4,761 simple transfers per second, 1,500–3,000 ERC20 transfers, or about 500–1,000 swap operations (data derived from block explorer records). Based on current parameters, opBNB’s TPS limit is 40 times that of Ethereum, over twice that of BNB Chain, and over six times that of Optimism.

Of course, Ethereum Layer2s are severely constrained by their DA layer, preventing the execution layer from performing at full capacity. Factoring in DA layer block times, stability, and other previously mentioned elements, Ethereum Layer2s’ real-world performance is drastically lower than their theoretical execution limits. In contrast, for high-throughput DA layers like BNB Chain, an execution layer scaling multiplier of over 2x makes opBNB highly valuable—and BNB Chain can host multiple such scaling solutions.

It is foreseeable that BNB Chain has already incorporated Layer2 solutions like opBNB into its strategic roadmap, planning to integrate more modular blockchain projects in the future—including introducing ZK proofs into opBNB and combining it with complementary infrastructure like GreenField to offer highly available DA layers—aiming to compete or collaborate with the Ethereum Layer2 ecosystem. In this era where layered scaling has become a dominant trend, whether other public chains will follow BNB Chain’s lead in nurturing their own Layer2 projects remains to be seen. But undoubtedly, the infrastructure paradigm shift toward modular blockchains is already underway and unfolding.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News