The Most Sophisticated ZK Application: A Brief Analysis of Tornado Cash's Principles and Business Logic

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Most Sophisticated ZK Application: A Brief Analysis of Tornado Cash's Principles and Business Logic

Tornado Cash can obscure the link between withdrawers and depositors; in cases with a large number of users, it's like a busy downtown area where a suspect becomes hard to track after blending into the crowd.

Author: Faust, Geek web3

Introduction: Recently, Vitalik and several scholars co-authored a new paper mentioning how Tornado Cash could implement anti-money laundering solutions (essentially allowing withdrawers to prove their deposit records belong to a set that does not contain illicit funds). However, the paper lacks a detailed explanation of Tornado Cash's business logic and principles, leaving readers with only a vague understanding.

It is also worth noting that privacy projects represented by Tornado are among the few that truly leverage the zero-knowledge property of ZK-SNARKs. In contrast, most rollups touting "ZK" primarily use only the succinctness of ZK-SNARKs. People often confuse Validity Proofs with true Zero-Knowledge proofs, making Tornado an excellent case study for understanding real-world ZK applications.

The author previously wrote an article on the mechanics of Tornado in 2022 for Web3Caff Research. Today, we excerpt and expand upon parts of that piece to provide a systematic understanding of Tornado Cash.

The Mechanics of the "Tornado"

Tornado Cash is a mixer protocol leveraging zero-knowledge proofs. The old version launched in 2019, while the new version entered beta at the end of 2021. The legacy version of Tornado is largely decentralized—its on-chain contracts are open-source with no multi-sig control, and its frontend code is open-source and backed up on IPFS. Since the older version has a simpler and more intuitive architecture, this article will focus on analyzing that version.

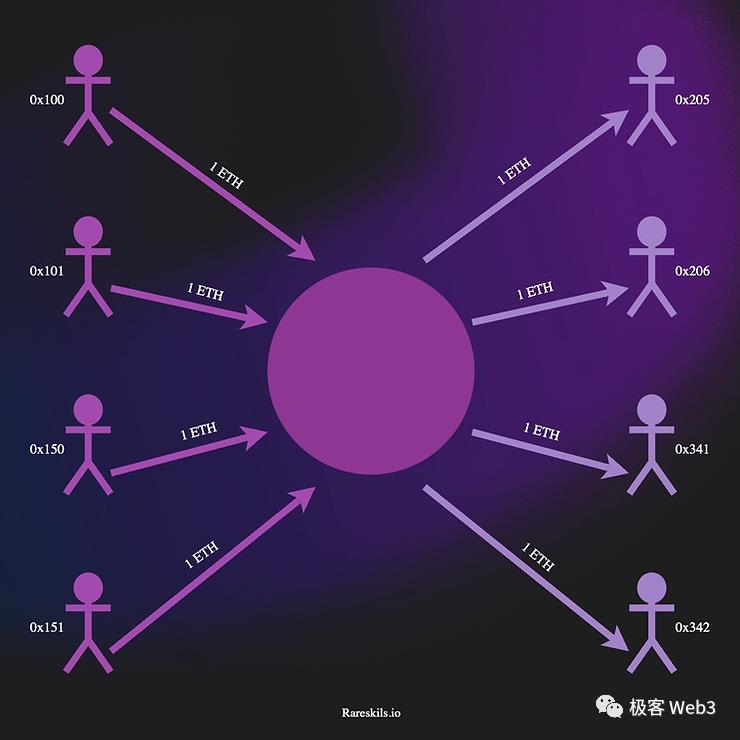

The core idea behind Tornado is: to mix numerous deposit and withdrawal actions together. After depositing tokens into Tornado, users present a ZK proof proving they made a deposit, then withdraw using a new address—thereby breaking any link between deposit and withdrawal addresses.

More concretely, Tornado operates like a glass box filled with coins deposited by many individuals. We can see who put the coins in, but since the coins are highly fungible, when a new person takes one out, it becomes difficult to determine whose original deposit it came from.

This scenario isn't entirely unfamiliar: when we swap ETH from a Uniswap pool, we have no way of knowing which liquidity provider’s ETH we received, as so many people have contributed. But the difference lies in the fact that each time you swap tokens via Uniswap, you must pay an equivalent cost in other tokens, and you cannot privately transfer funds to someone else. In contrast, a mixer only requires the withdrawer to present a deposit credential.

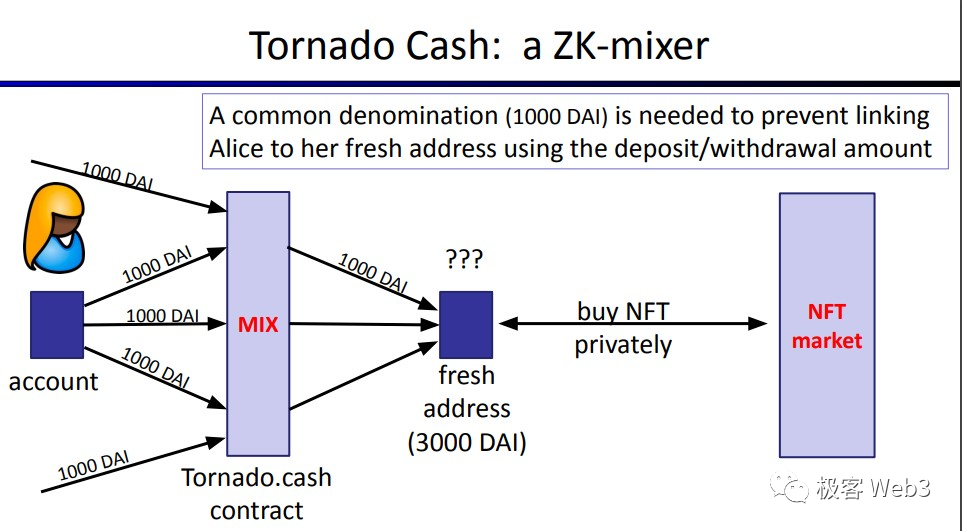

To make deposit and withdrawal actions appear homogeneous, every deposit into a given Tornado pool and every withdrawal from it involves the same amount. For example, in a pool with 100 depositors and 100 withdrawers, although all participants are publicly visible, there appears to be no connection between them—and each deposits and withdraws the exact same amount. This creates ambiguity, preventing linkage based on transaction amounts and thus severing traces of fund transfers. Clearly, this provides natural convenience for money laundering activities.

But here arises a critical question: How does a withdrawer prove they actually made a deposit? The withdrawal address bears no visible link to any deposit address—so how can withdrawal eligibility be verified? The most straightforward method would be for the withdrawer to disclose exactly which deposit record belongs to them, but that would directly expose their identity. This is where zero-knowledge proofs come into play.

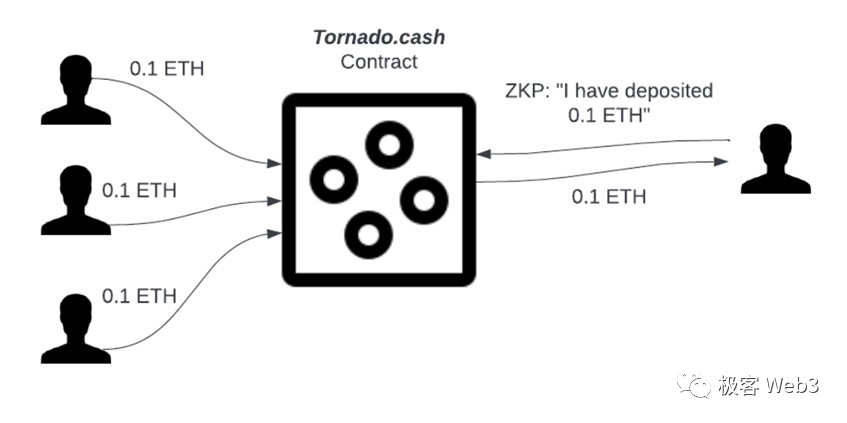

A withdrawer submits a ZK Proof demonstrating they have a deposit record within the Tornado contract and that the deposit hasn’t been withdrawn yet—enabling them to initiate a withdrawal. The zero-knowledge proof itself ensures privacy: outsiders know the withdrawer did deposit funds into the pool, but cannot determine which specific depositor they correspond to.

Proving “I deposited funds into Tornado” can be rephrased as “My deposit record exists within the Tornado contract.” If we denote a deposit record as Cn, the problem becomes:

Given the set of Tornado deposit records {C1, C2, ..., C100, ...}, withdrawer Bob proves he used his private key to generate one of these records Cn—but uses ZK techniques to hide which specific Cn it is.

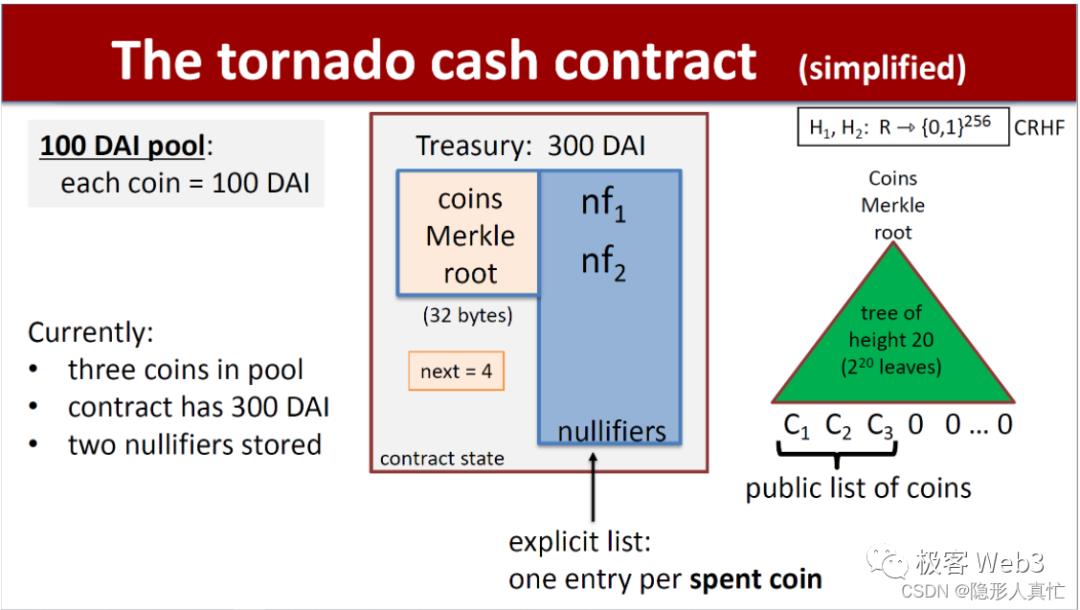

Here, we utilize a special property of Merkle Proofs. All Tornado deposit records are stored as leaf nodes at the bottom layer of a Merkle Tree constructed on-chain, with approximately 2^20 leaves—over a million—most of which remain empty (initialized with default values). Whenever a new deposit occurs, the contract writes the corresponding commitment value into one of the leaves and updates the Merkle Tree root.

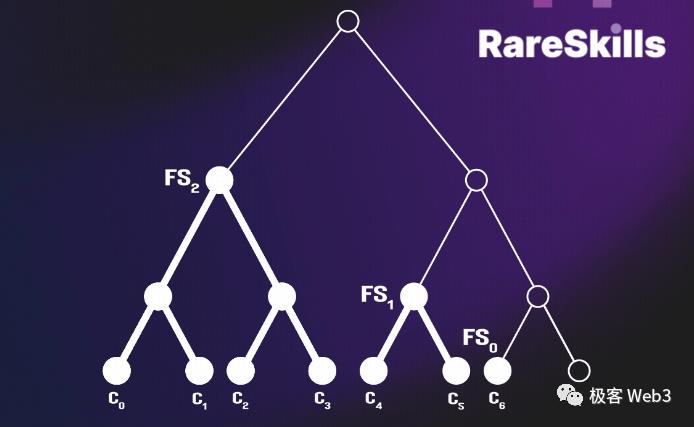

For instance, if Bob’s deposit is the 10,000th transaction ever made in Tornado, the associated commitment Cn will be written into the 10,000th leaf node—i.e., C10000 = Cn. The contract then automatically computes the new Root and updates it. (Note: To save computation, the Tornado contract caches data from previous batches of changed nodes, such as Fs1, Fs2, and Fs0 shown below.)

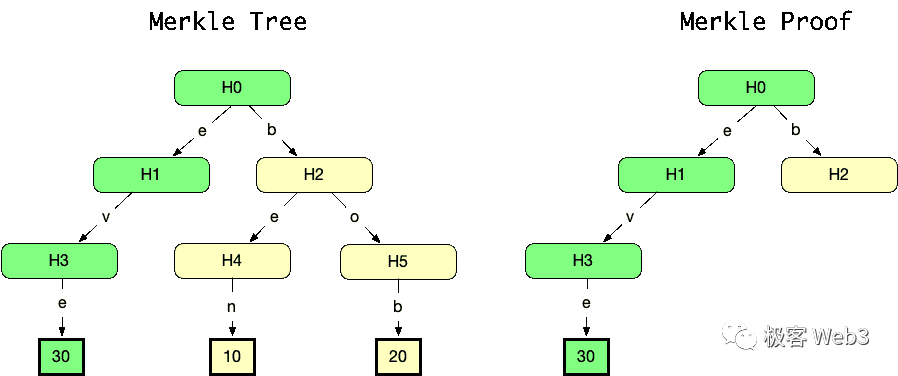

Merkle Proofs are inherently concise and lightweight, leveraging the efficiency of tree structures during retrieval and verification. To prove that a certain transaction TD exists within the Merkle Tree, one only needs to provide the corresponding Merkle Proof (as shown on the right side of the image below), which remains extremely compact. Even if the Merkle Tree contains 2^20 leaves—over a million entries—the Merkle Proof requires just 21 node values, remaining very short.

To prove that a particular hash H3 is indeed included in the Merkle Tree, one demonstrates that combining H3 with certain auxiliary data from the tree allows reconstruction of the Root. That auxiliary data—including Td—constitutes the Merkle Proof.

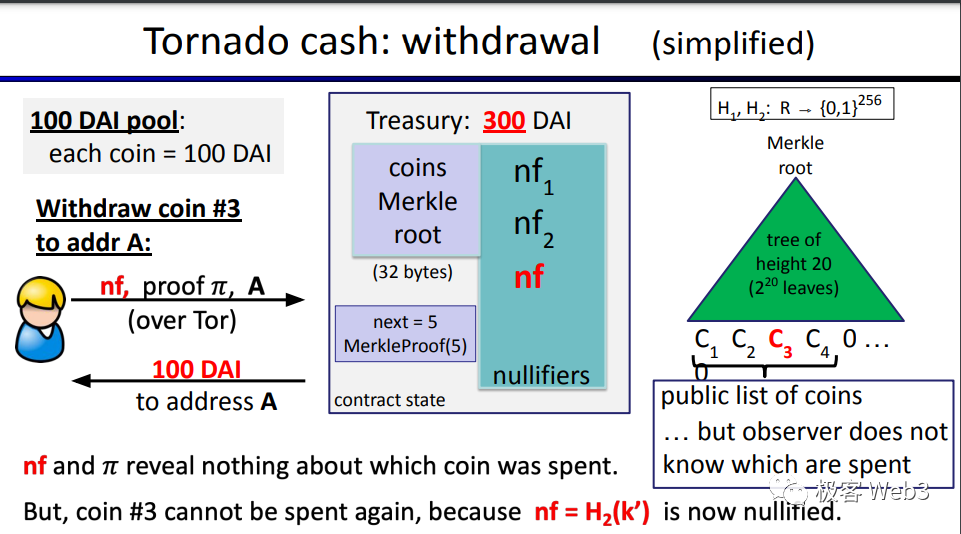

When Bob withdraws, he must prove his credentials correspond to some recorded deposit hash Cn in the Merkle Tree. Specifically, he must prove two things:

· Cn exists within the Merkle Tree stored in the on-chain Tornado contract—this can be proven by constructing a Merkle Proof containing Cn;

· Cn is linked to Bob’s deposit credentials.

Detailed Breakdown of Tornado’s Business Logic

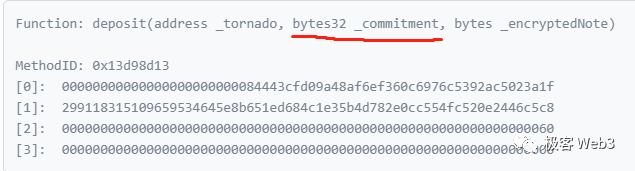

The frontend interface of Tornado Cash comes with pre-implemented functionality. When a user opens the Tornado Cash website and clicks the deposit button, the bundled program in the frontend code generates two random numbers K and r locally, computes Cn = Hash(K, r), and sends Cn (known as the commitment, seen in the diagram below) to the Tornado contract, inserting it into the Merkle Tree maintained by the contract. Essentially, K and r act as private keys. They are crucial, and users are prompted to store them securely, as they will be needed again during withdrawal.

(The encryptedNote feature is optional, allowing users to encrypt and store their credentials K and r on-chain to prevent loss.)

Notably, all of the above happens off-chain: neither the Tornado contract nor external observers know K or r. If K and r are leaked, it is akin to having your wallet’s private key stolen.

Once the Tornado contract receives the user’s deposit and the submitted Cn = Hash(K, r), it inserts Cn as a new leaf node at the bottom of the Merkle Tree and updates the Root value. Thus, Cn is uniquely tied to the deposit action. Outsiders can observe which user corresponds to each Cn, seeing who has deposited tokens into the mixer and knowing each depositor’s associated record Cn.

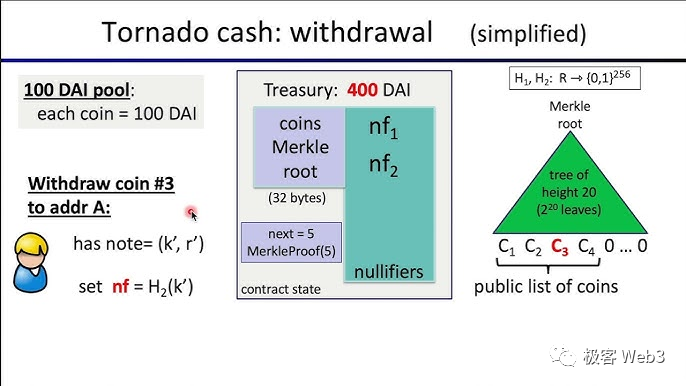

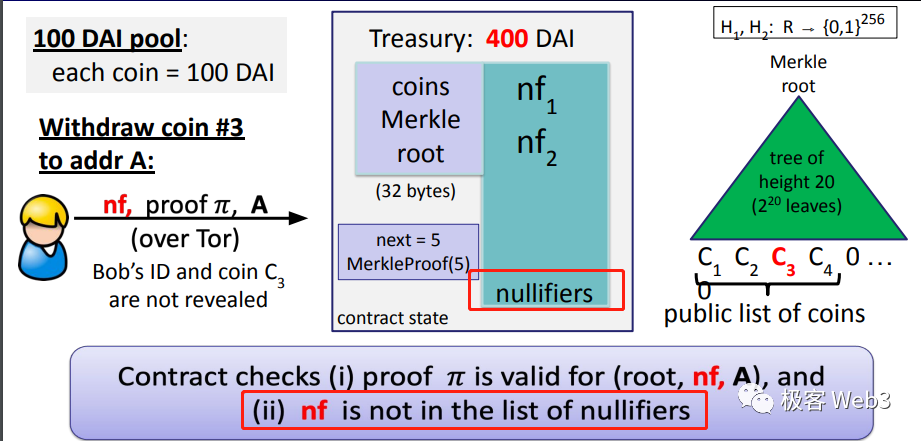

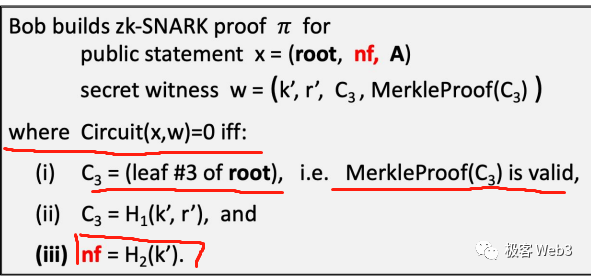

During withdrawal, the user inputs their credentials/private keys (the random numbers K and r generated during deposit) into the frontend. The Tornado Cash frontend program then uses K and r, Cn = Hash(K, r), and the Merkle Proof corresponding to Cn as input parameters to generate a ZK Proof, proving that Cn is a valid deposit record in the Merkle Tree and that K and r are the correct credentials for that record.

This step effectively proves: I know the secret key corresponding to some deposit record stored in the Merkle Tree. When the ZK Proof is submitted to the Tornado contract, these four parameters remain hidden—neither the public nor the contract learns them—thus preserving privacy.

Additional parameters involved in generating the ZK Proof include: the current Merkle Tree root in the Tornado contract at withdrawal time, a custom recipient address A, and a replay-prevention identifier nf (explained later). These three parameters are published publicly on-chain and are visible to all, but do not compromise privacy.

An important detail: Two random numbers K and r are used to generate Cn instead of just one. This is because using a single random number is less secure and risks collision—two different depositors might accidentally pick the same random number, resulting in identical Cn values.

Regarding A in the diagram, it represents the address receiving the withdrawal, filled in by the withdrawer themselves. nf is a replay attack prevention identifier, calculated as nf = Hash(K), where K is one of the two random numbers used during deposit (K and r). As such, nf becomes linked to Cn—each Cn has a unique corresponding nf, forming a one-to-one mapping.

Why prevent replay attacks? Due to the design of mixers, during withdrawal it's impossible to know which leaf node Cn the withdrawn coin corresponds to, nor which depositors are linked to the withdrawer—making it unclear how many times the user may have deposited. A malicious actor could exploit this to repeatedly withdraw, launching a replay attack and draining the entire pool.

Here, the role of the nf identifier is similar to the nonce used in every Ethereum account, both designed to prevent transaction replays. During a withdrawal, the user must submit an nf, which the system checks against a record of previously used nf values. If already used, the withdrawal is invalid. If unused, the withdrawal proceeds, and the nf is recorded. Any future attempt to reuse this nf will be rejected.

Can someone fabricate an arbitrary nf not recorded by the contract? No—they cannot. Because when generating the ZK Proof, the withdrawer must ensure nf = Hash(K), and K is tied to the original deposit record Cn. Therefore, nf is cryptographically bound to a legitimate deposit. A fabricated nf would fail to match any existing deposit, making it impossible to generate a valid ZK Proof—rendering the entire withdrawal process unsuccessful.

One might ask: Is nf even necessary? Since the withdrawer must submit a ZK Proof linking them to a Cn, couldn't we simply check whether that ZK Proof has already been submitted on-chain?

In practice, this would be too costly. The Tornado Cash contract does not permanently store past ZK Proofs, as doing so would waste significant storage space. It is far more efficient to use a small identifier like nf and store it permanently rather than comparing every newly submitted ZK Proof against all historical ones.

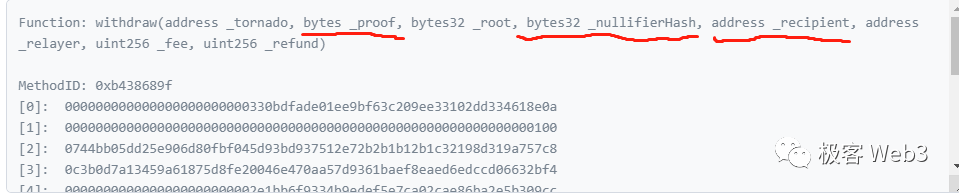

The withdrawal function, illustrated in code, requires the following parameters and follows this logic:

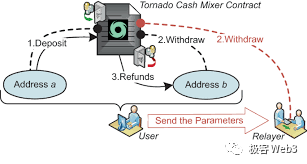

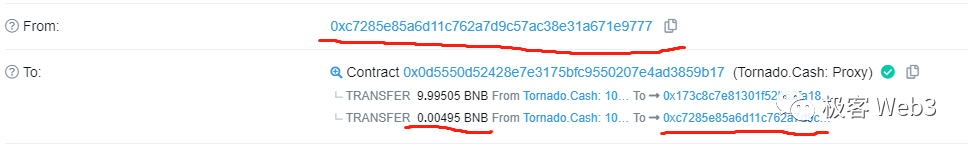

The user submits the ZK Proof, nf (NullifierHash) = Hash(K), and specifies a recipient address. The ZK Proof hides the values of Cn, K, and r, preventing outsiders from identifying the user. The recipient address is typically a fresh, clean address that reveals no personal information.

However, there is a minor issue: to avoid traceability, users often initiate withdrawals from newly created addresses, which usually lack ETH to pay gas fees. Therefore, when initiating a withdrawal, the user must explicitly declare a relayer to cover the gas fee. The mixer contract then deducts a portion of the withdrawn amount and forwards it to the relayer as compensation.

In summary, TornadoCash successfully conceals the link between depositors and withdrawers. With a large user base, it resembles a crowded urban area where a suspect can vanish into the crowd, evading detection. The withdrawal process relies on ZK-SNARKs, with the witness data—containing sensitive user information—kept hidden. This is the most crucial aspect of the entire mixing mechanism. Currently, Tornado stands as one of the most ingenious application-layer projects leveraging zero-knowledge technology.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News