A Brief History of Airdrops and Anti-Witch Strategies: On the Tradition and Future of Farming Culture

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Brief History of Airdrops and Anti-Witch Strategies: On the Tradition and Future of Farming Culture

Know yourself and know your enemy, and you can fight a hundred battles without danger of defeat.

Author: DefiOasis

Introduction: This is an airdrop/farming history every yield farmer should read, and also a rather interesting科普 article on yield farming.

Understanding the history of a field allows one to better "know oneself and know the enemy, and a hundred battles will bring no danger of defeat."

The Origins of Airdrops

"Getting rewards at nearly zero cost." "Money isn't earned—it's blown in by the wind." These are voices left by airdrop farmers on social media in recent years. This form of free-grabbing has long been common in Web2's early cash-burning user subsidy—price war strategies. However, compared to that, Web3’s direct cash “subsidy” model is even more eye-catching. After a series of wealth creation myths fueled by ENS, DYDX, and other airdrops, the entire Web3 space fell into a gold-rush frenzy over airdrop farming.

The earliest known Web3 airdrop traces back to a programmer named Baldur Friggjar Odinsson, who issued AuroraCoin in 2014 and airdropped 31.8 tokens each to 330,000 citizens of Iceland.

However, Uniswap is widely recognized as the pioneer of modern airdrops. To counter Sushiswap’s vampire attack, Uniswap distributed at least 400 UNI tokens to every address—worth over $1,000 minimum. Witnessing Uniswap’s powerful user acquisition effect from its airdrop, major projects like 1inch and LON quickly followed suit, catalyzing the DeFi Summer of 2020 to some extent. As terms like Web3 and DAO gained popularity, airdrops became an unwritten tradition for decentralization among projects—an integral part of blockchain culture.

Interestingly, airdrop issuers can be divided into two categories: "VC-backed projects" and "community-driven projects." This article primarily focuses on VC-backed projects.

Key Purposes of Airdrops

1. Marketing and Promotion

In recent years, airdrops have become a standard component for most projects. A well-executed airdrop campaign can instantly amplify a project's visibility. For yield farmers, receiving an airdrop builds positive sentiment toward the project. Farmers voluntarily showcase their gains on social media, creating a chain reaction that further intensifies public attention.

Many projects aim to generate breakout effects through airdrops, attract new users, and strengthen engagement with early adopters. In sectors such as DeFi and NFTs, airdrop distribution has also become one of the key methods for capturing market share and launching “vampire attacks” against competitors.

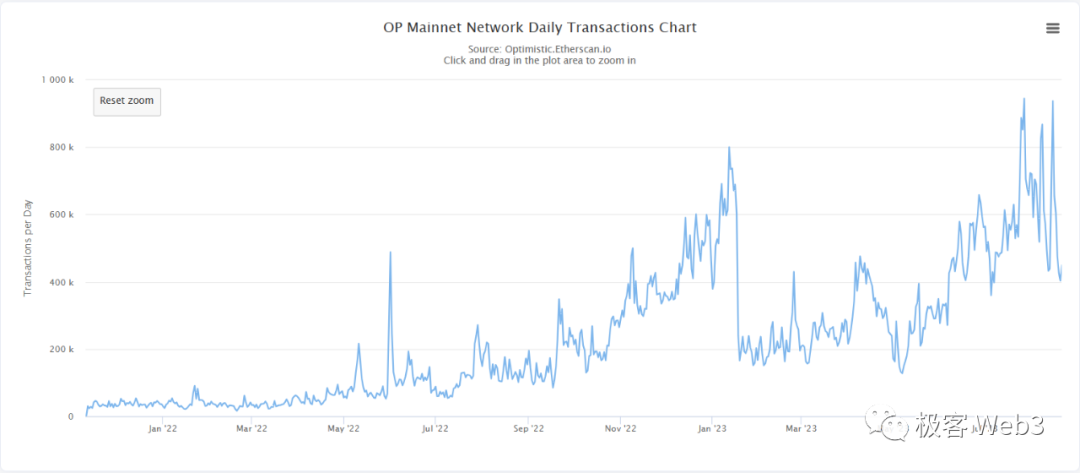

(Daily transaction count on OP chain remained high after the airdrop)

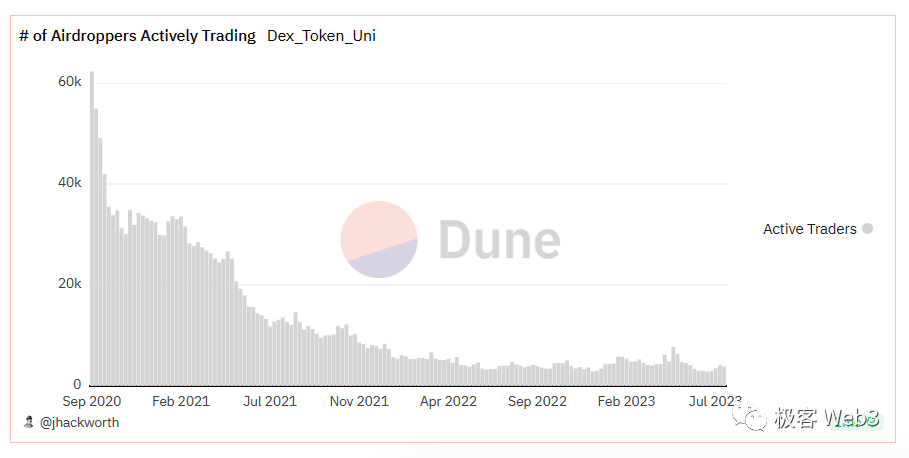

While airdrops drive user acquisition, evidence suggests they do little to improve actual user loyalty. According to Dune user @jhackworth’s Uniswap dashboard, only 6.2% of addresses that received the UNI airdrop still hold it, and those who remain active weekly represent less than 2% of Uniswap’s weekly active addresses, contributing only 1% of total trading volume.

Although this decline may partly result from growth in non-airdropped users, the sustained drop in weekly activity among airdropped addresses (as shown above) indicates that the UNI airdrop did not significantly enhance user stickiness as expected.

2. Token Decentralization

After completing early development, many projects transfer partial governance responsibilities by establishing DAOs to achieve decentralization. Most PoS public chains have stronger demands for token decentralization than DeFi projects, so they often distribute tokens via airdrops or public sales.

To reduce concentration of token holdings among early VCs and the founding team, most projects distribute portions of tokens to the community or early users. Community members then help redistribute these tokens further, spreading ownership across more individuals.

The Game Between Farmers and Projects

1. Witch Hunts – The Cat-and-Mouse Game

Sybil attacks were first proposed in 2002 by John R. Douceur of Microsoft Research, inspired by the 1973 novel *Sybil*, whose protagonist Sybil Dorsett suffered from dissociative identity disorder with 16 distinct personalities. In the digital world, a Sybil attack refers to creating numerous fake identities/accounts to appear as multiple separate entities, all controlled by a single actor aiming to gain power or profit.

Sybil attacks have existed since Web1. In the context of token airdrops, due to blockchain’s permissionless nature and lack of KYC mechanisms, combined with strong anonymity and low cost of creating on-chain addresses, attackers easily use one physical person to create thousands of addresses to claim multiple airdrop rewards.

Project teams usually intend to reward real users, aligning interests. While farming activities temporarily boost impressive user metrics for projects, Sybil addresses typically dump their rewards immediately and disappear afterward—clearly contradicting project goals.

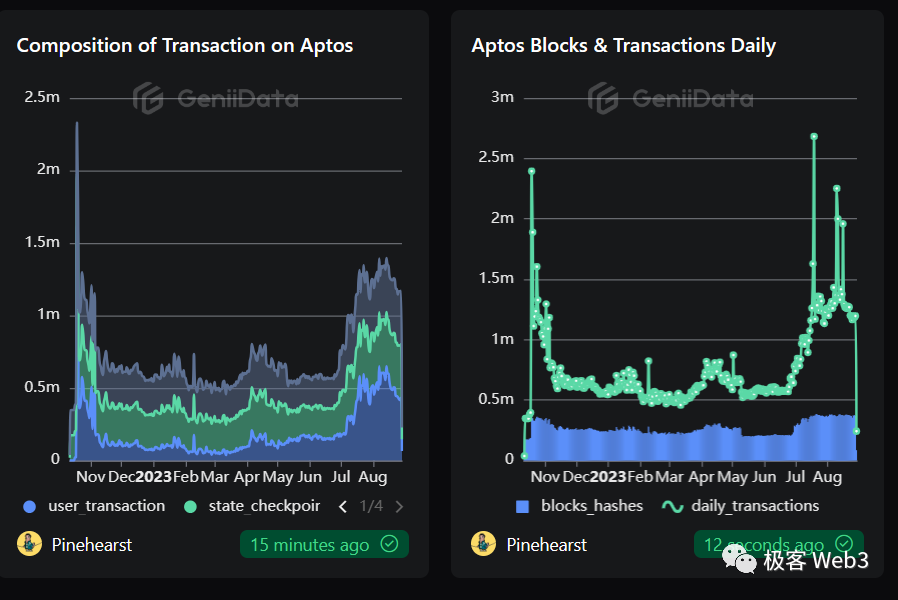

(Aptos, which didn’t implement anti-Sybil checks, saw transaction volume spike briefly during airdrop distribution, then remain depressed for long periods)

Thus, dedicated “witch hunts” became inevitable, and various anti-Sybil measures emerged:

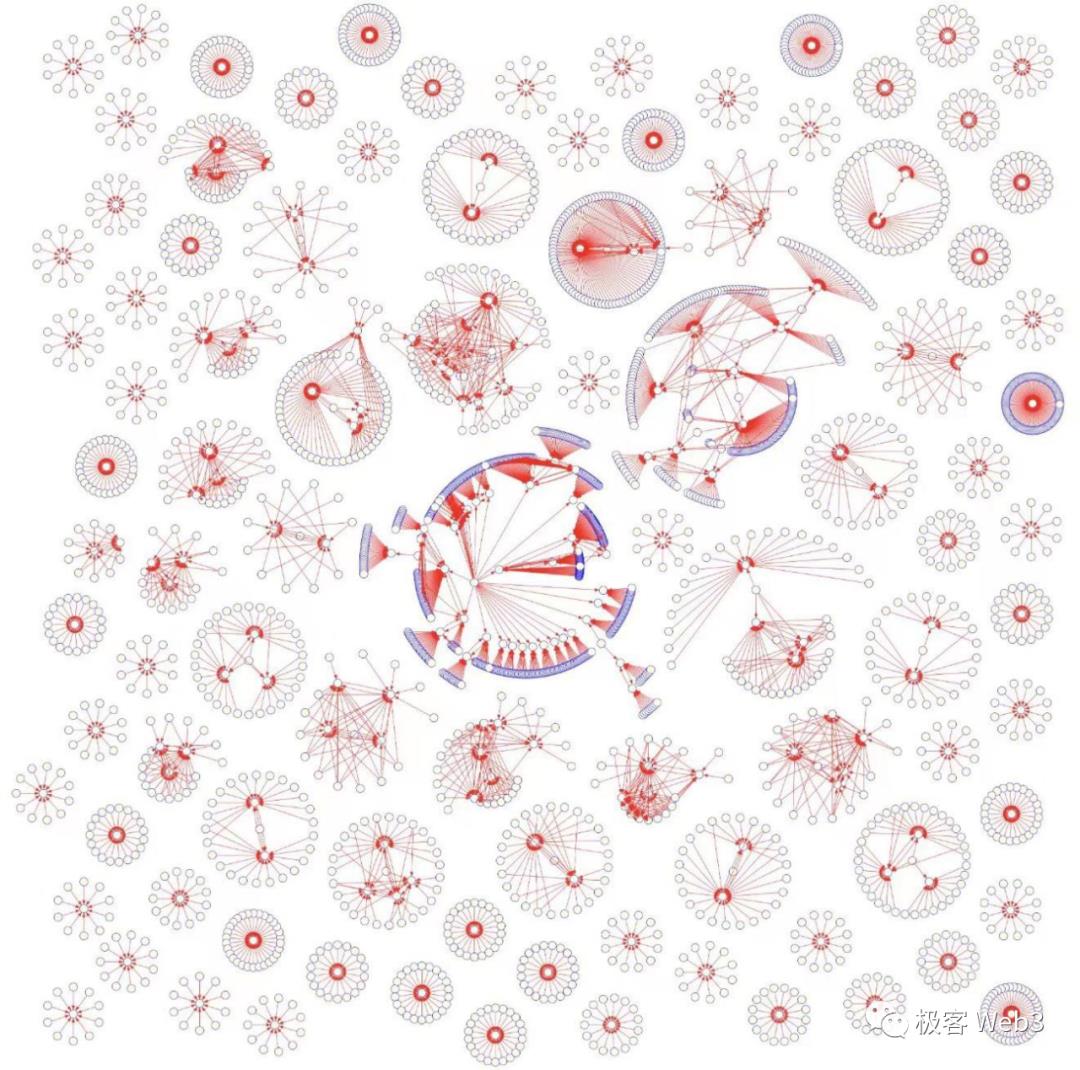

On-chain behavior analysis: This method relies heavily on analyzing on-chain data—such as fund connections between addresses (fund distribution or consolidation, transfer patterns), behavioral similarity (interacted smart contracts, transaction intervals, timing, active hours)—to filter suspicious addresses. It remains the most common screening approach.

Depending on project tolerance, generally up to 10–20 related addresses per individual are allowed. Some projects delegate enforcement to the community, rewarding contributors who report Sybil addresses with confiscated airdrop allocations. This encourages active reporting; notable examples include Hop Protocol and Connext. But as the saying goes, “for every inch of progress, the devil advances a foot.” Yield farmers continuously upgrade their sophistication, making advanced players highly resistant to detection.

(One of Connext community reports based on contributor submissions identifying Sybil addresses)

Reputation scoring: Reputation systems assess factors such as a user’s cross-chain activity (on-chain activity level, transaction volume, gas spent), identity verification on established apps (ENS, Lens, etc.), participation in on-chain governance (Snapshot, Tally), and NFT collection history. By combining multi-dimensional indicators, these systems evaluate an address’s credibility and likelihood of being bot-controlled.

This method mainly uses reputation scores to identify Sybil addresses, significantly increasing the cost of malicious behavior (similar in principle to Proof of Work). Gitcoin Passport, Phi, and Nomis are representative reputation-based projects. However, some platforms exhibit bias by giving higher score weights to users of their own products, or setting high capital thresholds to favor whales, sometimes requiring submission of Web2 account info (Twitter, Google, Facebook) to verify real human identities behind addresses.

Biometric verification: Biometric traits such as iris, fingerprint, and facial features are unique and immutable, making them hard to forge. For airdrop issuers, biometric verification ensures rewards mostly go to real humans. However, this process is inefficient, and controversies surrounding Worldcoin’s iris scanning and Sei’s facial recognition highlight serious privacy concerns. There are also legal risks across different jurisdictions when collecting biometric data.

Other mainstream anti-Sybil approaches include KYC using government-issued IDs (driver’s license, passport, ID card), soulbound tokens (SBTs), POAPs awarded through in-person or online verification events, and Proof of Humanity.

In practice, reasonable witch hunts help maintain fairness in reward distribution. Yet overly strict Sybil checks risk penalizing legitimate users, and delegating review power to communities may damage trust and deepen divisions.

Regardless of the anti-Sybil method used, completely filtering out bad actors is unrealistic. When potential profits exceed costs, Sybil attacks become inevitable (even PoW and PoS cannot fully stop Sybil nodes, only deter them to large degrees). Thus, this cat-and-mouse game will persist indefinitely.

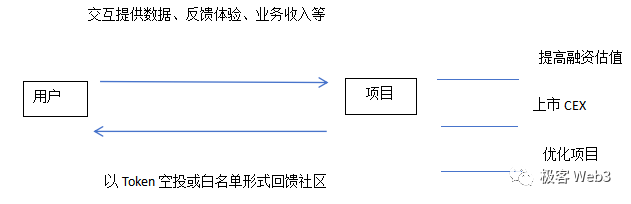

2. Shared Fate: Rise Together, Fall Together

Projects and users appear locked in strategic博弈, where opposition manifests not just in Sybil vs anti-Sybil dynamics, but also in how projects subtly signal future airdrops or launch Odyssey-style missions to manage farming expectations—essentially PUAing users into interactions. Without knowing whether an airdrop exists or how it will be allocated, farmers take on financial risk hoping for future rewards, thereby pressuring projects to issue airdrops or whitelist privileges.

Despite apparent conflict, both sides enjoy symbiotic, mutually beneficial relationships. On one hand, farming activity constitutes a significant portion of on-chain engagement metrics, helps uncover bugs early, improves product experience (effectively stress-testing infrastructure—both OP and ARB faced performance issues upon airdrop release), generates business revenue, and provides essential data for valuation or CEX listings. In a Web3 ecosystem historically driven by wealth creation narratives, many projects rely on “feeding farmers” to survive prolonged bear markets.

On the other hand, farmers stand to benefit from future token distributions. Together, they co-create a "illusory prosperity."

Evolution of Airdrop Policies

1. The Escalating Arms Race Among Airdrop Issuers

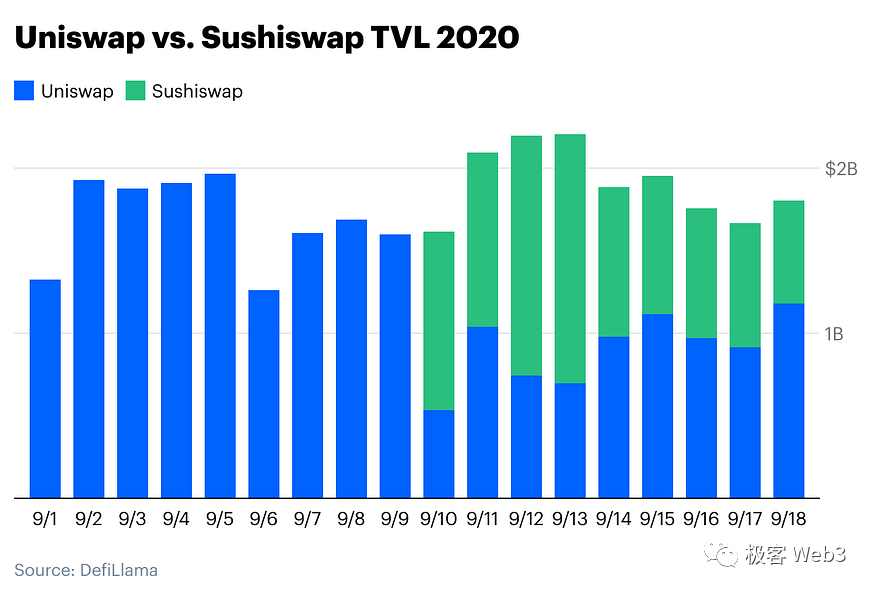

The story of competitive airdrop escalation begins with Uniswap. During the liquidity-is-king DeFi Summer of 2020, DeFi projects led by Sushi executed vampire attacks via liquidity mining incentives, siphoning off substantial user base and TVL from Uniswap (peaking at $1.2 billion). Under pressure, Uniswap made history by distributing massive amounts of UNI tokens and launching liquidity mining programs, successfully drawing users back and reclaiming its position as the leading DEX—a status it maintains today.

(In 2020, Sushi launched a vampire attack, capturing market share from Uniswap)

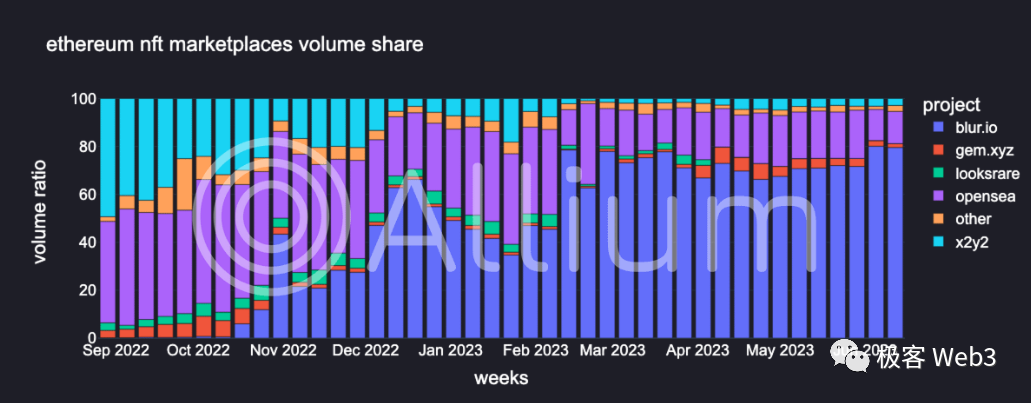

Today, airdrops have become standard weapons in intra-sector competition, used routinely to execute “vampire attacks” and capture users. Projects employ creative tactics to retain users. In the fiercely competitive Layer2 space, OP conducted multiple rounds of airdrops to pressure rivals. Recently, however, such airdrop-driven attacks have become more evident in the NFT sector. Before Blur maximized NFT liquidity, platforms like LooksRare and X2Y2 attempted to capture users via airdrops, yet lacked meaningful differentiation. Once expected returns dried up, user interest faded, volumes plummeted, and OpenSea’s dominance remained unshaken.

(Blur gradually eroding OpenSea’s established market advantage)

These cases serve as cautionary tales: utility and genuine demand remain key to user retention. Strong products build moats; airdrops merely complement them.

Today, Uniswap V4 remains the DEX benchmark; Blur alleviated NFT illiquidity during the bear market; Optimism provides solid infrastructure for Ethereum users as a top-tier Layer2. While airdrops brought temporary hype, projects lacking utility or real demand have been buried by history.

2. Farmers’ Own Internal Competition

From simple actions like leaving an email or joining a group chat, to deep, sustained involvement required for potential rewards, the airdrop landscape has transformed dramatically within just a few years. With too many users (and infinite addresses) chasing too few quality projects, the balance of power has shifted from users to project teams. Projects now manipulate farming expectations, launching “Odyssey” campaigns alone or with platforms like Galxe, Layer3, and Rabbithole to PUA users. The dynamic has flipped—from projects begging users to users begging for drops. Yield farmers, in turn, have developed their own “street smarts.”

3. Direction Matters More Than Effort

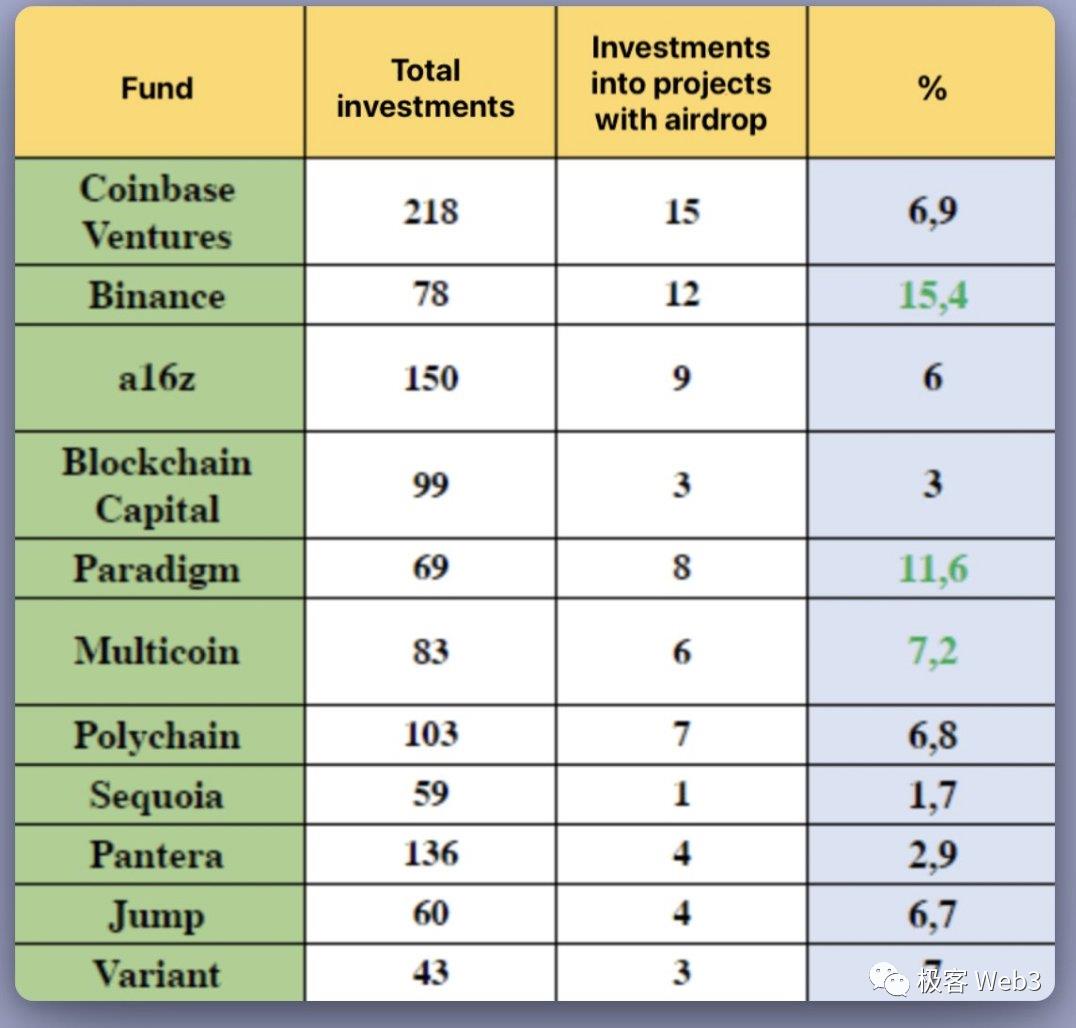

Many yield farmers closely follow projects backed by renowned firms such as A16Z, Paradigm, and Coinbase. They trust these investors' judgment for higher future token valuations and believe such projects have greater chances of conducting airdrops.

According to data compiled by airdrop analyst @ardizor, among prominent VCs, Binance, Paradigm, and Multicoin have the highest rates of investing in projects that later conduct airdrops, at 15.4%, 11.6%, and 7.2% respectively.

(Airdrop rates of selected famous VCs. Source: @ardizor)

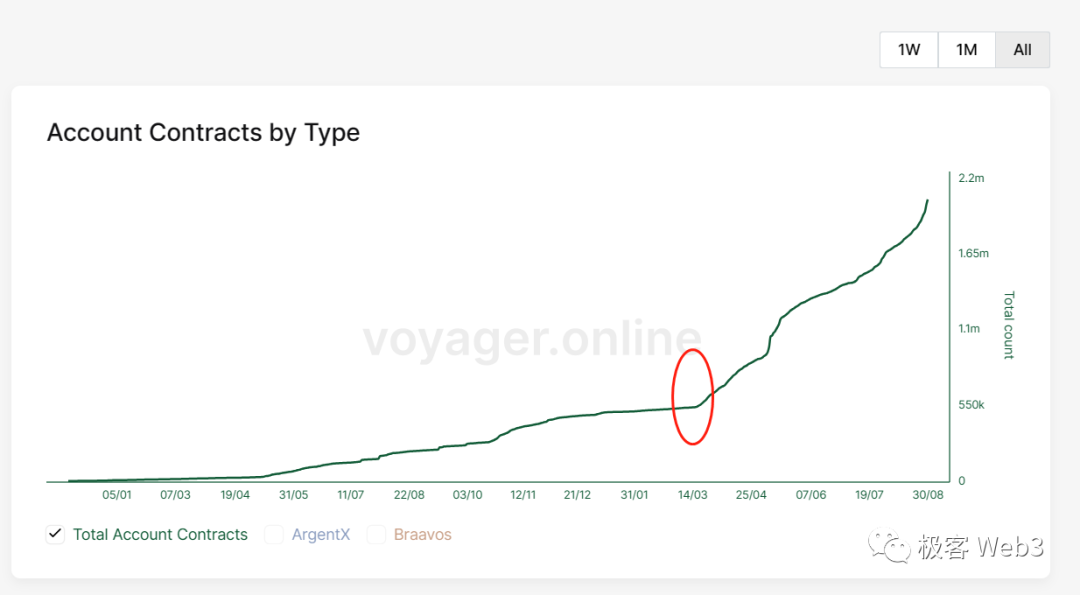

Among VC-backed projects, farmers also favor those with large funding rounds. High funding implies stronger cash flow and brighter prospects, suggesting more generous future airdrops. When backed by reputable VCs and large funding, the odds of valuable airdrops increase, prompting farmers to vote with their wallets—betting on high-profile, well-funded, yet-to-launch-token projects such as zkSync, Starknet, Aleo, Aztec, and LayerZero. Currently, zkSync (~4 million active addresses), Starknet (~2 million), and LayerZero (~3 million) are the most densely farmed ecosystems.

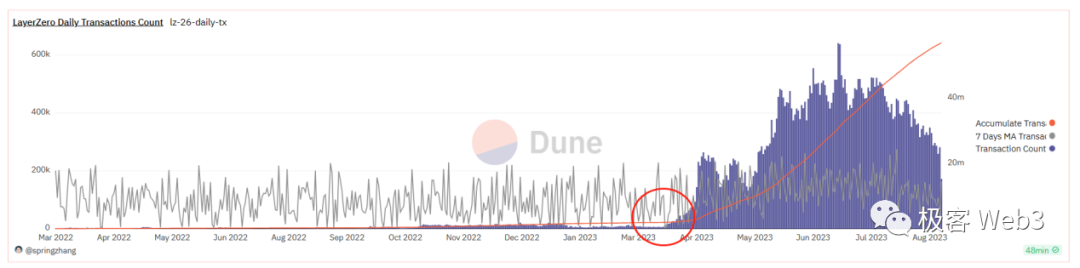

(After Arbitrum's airdrop, address counts and daily active users surged sharply for three projects—LayerZero and Starknet—with over $100M in funding. ZkSync Era grew by at least 5,000 new active addresses daily since its mainnet launch in March)

4. The Harder You Work, the Luckier You Get

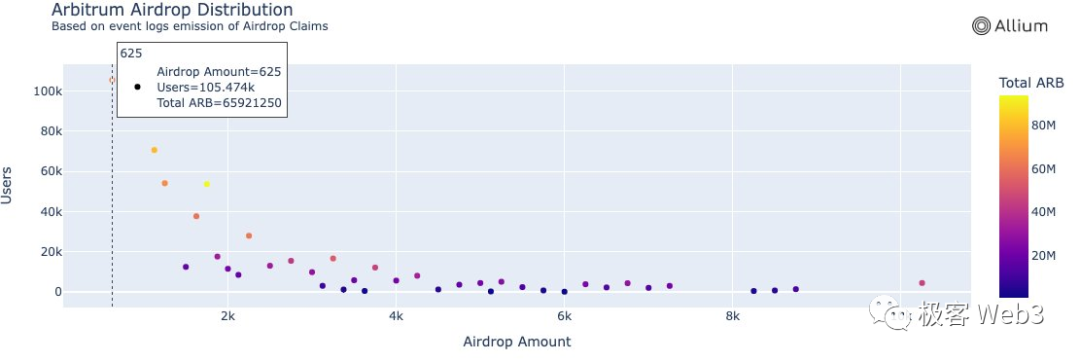

Excluding variable-supply airdrops like Worldcoin, Arbitrum’s February airdrop had the largest snapshot address count to date—nearly 2.3 million. As more farmers join and fixed airdrop pools remain unchanged, projects must narrow eligible recipients. Rather than intensifying Sybil scrutiny and risking backlash, many opt to raise eligibility barriers—filtering for high-quality users and distributing rewards more precisely. This has become standard practice.

Tiga from quant and venture firm W3.Hitchhiker identified general airdrop allocation patterns:

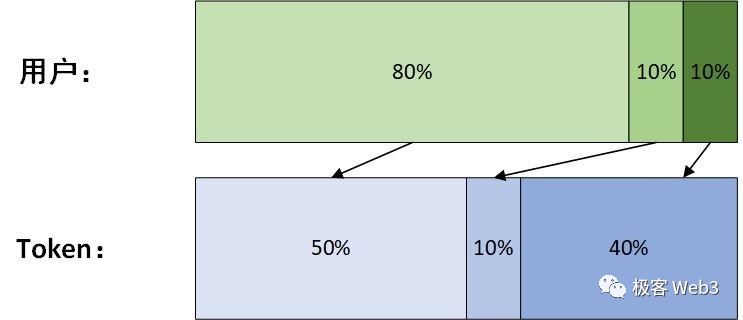

Base tier: ~50% of tokens allocated to bottom 80% of users (rank 0%–80%).

Mid tier: ~10% of tokens allocated to next 10% of users (rank 80%–90%).

Top tier: ~40% of tokens allocated to top 10% of users.

(The 80/20 rule applies to airdrops. Source: Tiga, W3.Hitchhiker)

This tiered system better stratifies users, disperses tokens widely among qualified participants to satisfy casual farmers, while rewarding major contributors generously. It creates a win-win scenario where everyone gets something suited to their contribution level, enhancing reputations within respective communities.

Currently, the most typical tiered models are “airdrop point systems,” which come in explicit and implicit forms.

Explicit point systems: Represented by mintfun, Blur, Arkham—projects openly announce airdrops but with uncertain value (partially estimable via valuation). Essentially, these are trade-mining or interaction-mining schemes using airdrops as bait. They tacitly allow some degree of Sybil activity, leveraging airdrop anticipation to maintain user loyalty.

Implicit point systems: Exemplified by Connext and Arbitrum—users don’t know if an airdrop exists beforehand. Implicit systems assign extra points for rare interactions or apply multipliers for specific behaviors, while deducting points for suspected bot-like actions.

As tiered airdrops grow common, disparities between smallest and largest rewards can exceed 10x. To maximize payouts, users must not only pick the right projects but also work harder. Hence, the concept of “premium accounts” emerged in farming circles—addresses meticulously crafted to mimic real users through targeted interactions across chains and similar projects. Based on research, farmers anticipate airdrop criteria and carefully calibrate time and money investment to barely meet “fully optimized” thresholds, appearing as deeply engaged users.

Yet whether through raised entry barriers or stricter Sybil checks, the ultimate cost falls on genuine users’ potential earnings.

(The harder you work, the luckier you get: Arbitrum widened the gap between light participants and major ecosystem contributors)

Has the Airdrop Space Turned Red Ocean?

Airdrops draw particular attention from Web3 users in economically disadvantaged developing countries. Driven by dollar purchasing power, low-cost/high-return incentives, and multi-address profit motives, most airdrop farms originate in these lower-income regions. After experiencing several major airdrops, farming studios now enjoy better cash flow to scale operations and are becoming increasingly professional—employing randomized interaction scripts, distributed independent IPs, and sophisticated anti-detection techniques to avoid wallet linking.

(Google Trends shows airdrop-related searches concentrated in low- and middle-income developing nations)

While some studios shut down due to cash flow or long airdrop cycles, most mature ones mitigate risks by offering farming-as-a-service, selling tools, maintaining thousands of interactive addresses. The sheer volume of addresses pressures projects—some, like Lens Protocol, impose access barriers, while most respond by raising airdrop thresholds, resulting in “active Sybils, zombie users” across the farming landscape.

Beyond this, following Arbitrum’s airdrop, multi-address-per-user behavior has become normalized, and an entire industry around airdrops is emerging: KOLs writing farming guides, identity verification providers for Sybil attackers, IP isolation and automation tool vendors, anti-Sybil agencies, and even hackers targeting farmers themselves—all reflecting the maturation of the airdrop ecosystem.

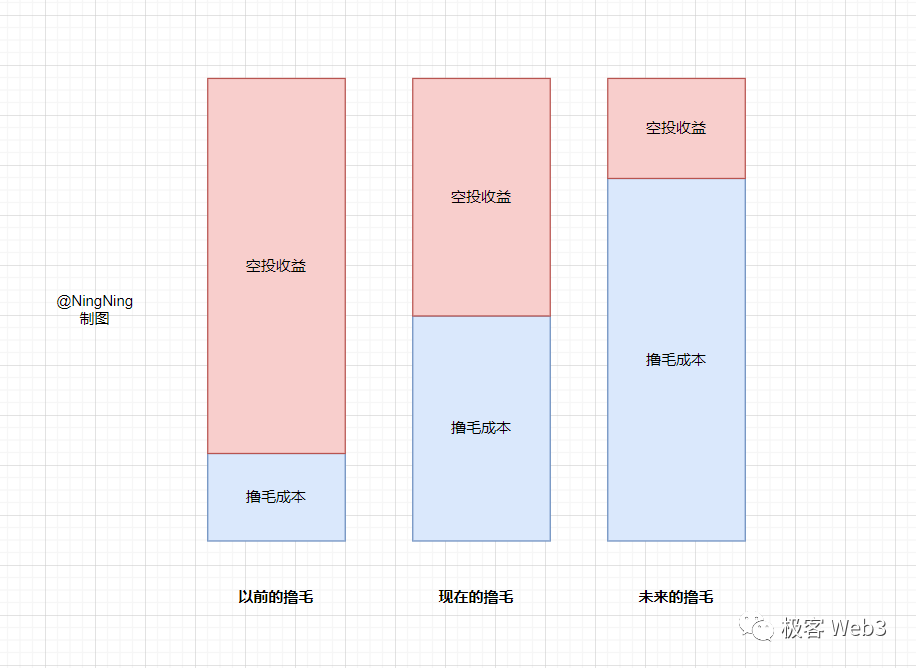

(Declining marginal returns of airdrops. Source: @0xNingNing)

Overall, in its early stages, the airdrop space offered risk-averse users seeking high returns a favorable “gambling” opportunity. As competition intensifies, expected returns inevitably decrease. If users treat airdropping—as sacrificing capital liquidity with uncertain payoff timelines—as an investment, then under rising anti-farming measures, Sybil risks, and shrinking yields, final returns might not even match simply dollar-cost averaging into spot assets during bear markets. From low-cost bets for outsized gains to costly “arbitrage,” the evolution of airdrops mirrors the broader transformation of crypto’s primary market.

Historically, CoinList-born 100x coins and GameFi’s play-to-earn models all cooled down as yield farmers flooded in. Everyone knows high-return models aren’t sustainable—the farmers merely accelerate their lifecycle.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News