In-depth Analysis of Token Issuance: Comparative Study and Summary of Initial Distribution Methods

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

In-depth Analysis of Token Issuance: Comparative Study and Summary of Initial Distribution Methods

What You Need to Know About Token Issuance

Written by: @Fu Shaoqing @Economic Model Team

Edited by: @Hei Yu Xiaodou

Preface

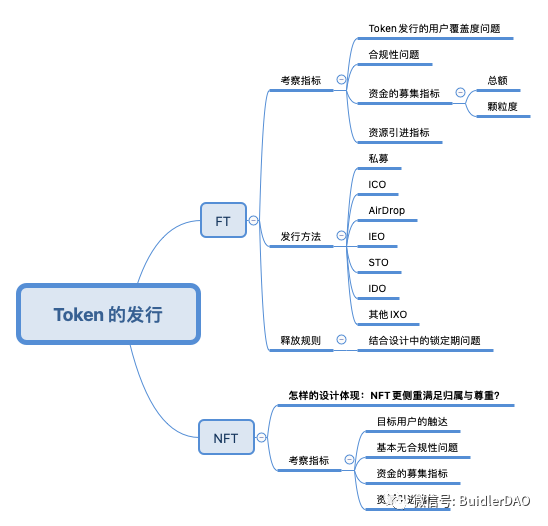

The Economic Model Team aims to study the overall process related to Tokens. This primarily includes several components: economic model design; Token issuance; and Token circulation management.

This article mainly discusses content related to Token issuance. With the development of blockchain and Web3 projects, many now include both FTs (Fungible Tokens) and NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens). Currently, academic research and practical applications have focused more on FT issuance, while studies and accumulated cases regarding the role and issuance of NFTs remain relatively limited. Dr. Xiao Feng from Wanxiang Blockchain published "Three-Token Model for Web3 Applications," which touches upon knowledge about NFTs. We also provide a brief analysis of NFT issuance in the final section of this article. The team will continue conducting in-depth research in this niche area in the future.

Token Issuance Fundamentals

Types of Tokens

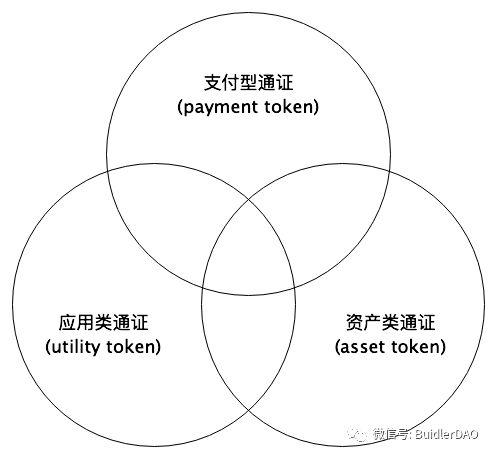

(1) Classification by Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA)

In 2018, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority classified tokens based on their potential economic functions. This classification method has gained significant international recognition. Following this relatively official and professional definition, tokens can be divided into three specific types:

-

Payment Tokens: These are used as a means of payment for goods or services, either currently or in the future—essentially functioning like money.

-

Utility Tokens: These exist digitally and are primarily used within blockchain-based applications or services, such as gas fees required for transactions.

-

Asset Tokens: These are backed by real-world assets, such as debt, equity, future company profits, or shares in asset flows. Economically, they resemble stocks, bonds, or derivatives. If fiat currency is considered an asset, stablecoins could also fall under this category.

These categories may overlap—some tokens exhibit characteristics of two or even all three types.

This classification aligns well with a financial and monetary perspective on tokens. In practice, project tokens often evolve over time: initially utility-focused, they gain monetary properties (as general equivalents) through application popularity, thus acquiring stronger payment functionality. Widely adopted tokens with high liquidity and value backing tend to further develop store-of-value attributes, making them more asset-like.

(2) Regulation-Oriented Classification: Utility vs. Security Tokens (also known as Application vs. Equity Tokens)

At its core, a token represents a carrier of value. By leveraging blockchain technology, value, rights, and physical assets can be tokenized. The underlying meaning of a token can represent rights such as dividends, ownership, or creditor claims; assets such as digitized real-world assets (corresponding to asset tokens); currencies such as BTC or USDT (payment tokens); or流通 tokens used within apps or services—many dApps issue their own tokens, falling into the utility token category. It can also represent anything of value, including creativity or attention.

In reality, some tokens are hybrid forms combining multiple types. For example, exchange-issued platform tokens may be partially backed by exchange profits (strong financial attributes), yet also offer various use cases (practical utility).

The concept of "token economics" emerged from these developments and is seen as highly promising. Its main features leverage inherent token properties to create superior ecosystems, better value models, larger user bases, and enable large-scale distributed value creation—echoing the essence of open-source collaboration.

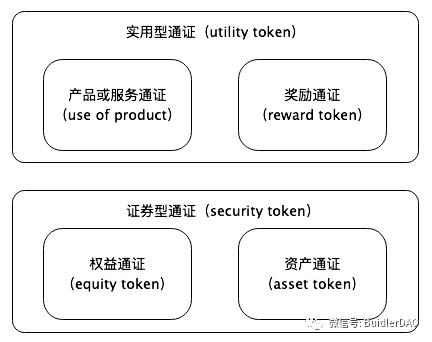

This regulation-oriented classification divides tokens into two major categories and four subcategories:

First Category: Utility Tokens

Product or Service Tokens (Use of Product): Represent access rights to a company's products or services.

Reward Tokens: Awarded to users based on certain behaviors or actions.

Second Category: Security Tokens

Equity Tokens: Analogous to corporate equity or bonds.

Asset Tokens: Correspond to real-world assets such as real estate or gold.

This categorization fits better with regulatory perspectives: Utility Tokens generally operate freely, while Security Tokens face strict oversight. However, if a Utility Token involves financial activities and exhibits securities-like features, it too becomes subject to regulation.

Note: Our previous article Four-Quadrant Token Economic Model (I): Dual FT Model provides detailed discussion on this topic.

Purposes of Token Issuance

Based on existing cases, Token issuance serves two primary purposes:

(1) Distribute Token to end users (to encourage application usage)

(2) Raise funds

Two types of Tokens: FT and NFT:

(1) FTs better reflect monetary characteristics, clearly fulfilling both objectives above. FT issuance requires finding individuals who recognize the FT’s value, which largely depends on the project’s future prospects.

(2) NFTs can also achieve these goals, but due to their unique nature and developmental history, there is less available material for analysis. (We discuss NFT issuance separately later.)

Evaluation Metrics for Token Issuance Methods

Based on the purpose of Token issuance, we summarize several preliminary evaluation metrics. Typically, compliance should rank first, but given the early-stage nature of the blockchain industry—where regulations and compliance frameworks are still evolving and unclear—we temporarily place compliance as the second criterion.

(1) User Coverage of Token Issuance: Targeting high-value Web3 users is common. Depending on the app’s characteristics, additional screening methods are needed to maximize coverage of target users. The ideal coverage varies per application.

(2) Compliance Issues: Based on the token’s nature and policies in major jurisdictions, compliant issuance methods or verification processes must be adopted.

(3) Fundraising Performance: Assuming compliance and adequate coverage, whether fundraising meets targets is a key metric. This includes both total amount raised and granularity (distribution across participants).

We consider lock-up periods for issued tokens part of design and post-issuance liquidity management, not an evaluation factor during the issuance phase.

Initial Token Issuance vs. Ongoing Project Token Issuance

In studying Token issuance cases, several standards emerge:

(1) Initial Total Supply (whether zero or non-zero)

(2) Fixed vs. Variable Total Supply (this dimension only affects later liquidity analysis and is beyond the scope of this article)

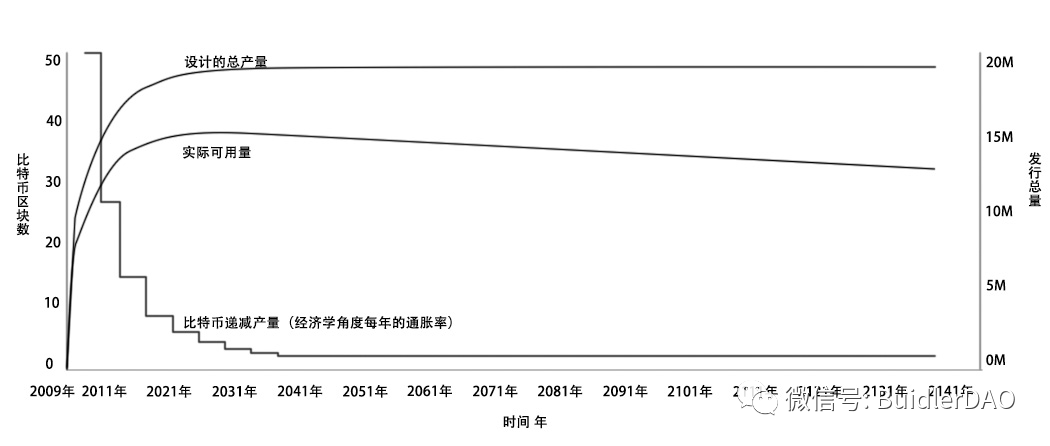

The diagram below illustrates an economic model with zero initial circulating supply (fixed total supply). Bitcoin exemplifies this type—there was no early token distribution. Later emissions via difficulty-adjusted mining mechanisms are outside this article’s scope and will be studied under post-issuance liquidity management.

Fixed-total token model (initial circulation = 0)

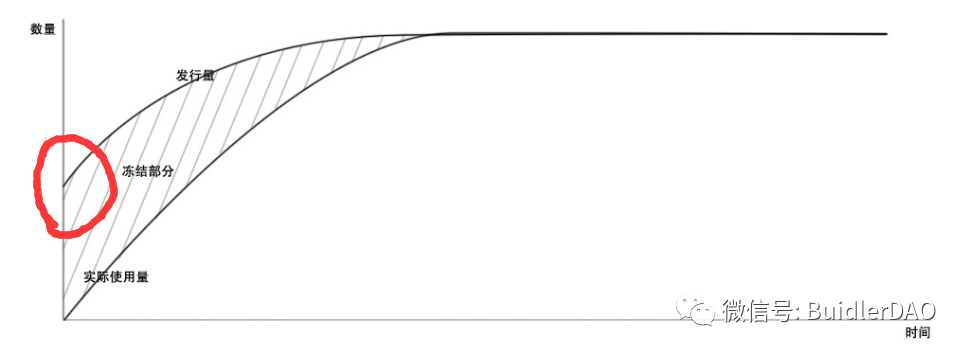

The next diagram shows models with non-zero initial supply, requiring issuance mechanisms to raise capital or precisely reach users. Ethereum is representative here—our focus is on public Token issuance methods like ICO, IEO, IDO, etc., covering the red circle area shown. Excess tokens beyond actual use require economic tools to freeze liquidity.

Fixed-total token model (initial circulation ≠ 0)

Tokens issued during project operation via PoW, PoS, or similar consensus mechanisms are considered part of post-launch liquidity management and are not discussed here.

Token Issuance Methods: IxO

In terms of Token issuance, there are two broad categories: private placement and public offering. This article focuses solely on public offerings; private placements do not involve the IxO methods discussed here.

Here’s a concise summary of common cryptocurrency issuance methods: Directly launching on a public chain is the original ICO; free distribution directly to user wallets is Airdrop; issuing via centralized crypto exchanges is IEO; cooperating with financial regulators is STO; launching on decentralized exchanges (DEXs) is IDO.

Private Placement

Private funds refer to investment funds that raise capital non-publicly from specific investors toward targeted investment goals. They rely on non-mass communication channels to pool funds from diverse, non-public entities.

In the Token space, private placements usually involve institutional or individual investors familiar with the field, typically arranged offline much like traditional financing. This evolved into SAFT (Simple Agreement for Future Tokens)—a mechanism where blockchain developers issue tokens to fund network development. Similar to futures contracts, SAFT grants investors the right to receive tokens once the blockchain network launches.

Due to strong compliance advantages, SAFT has been adopted by prominent projects such as Telegram and Filecoin. It is particularly suitable for utility tokens—though not securities upon launch, their fundraising for network construction constitutes an investment agreement, and SAFT clarifies compliance procedures.

According to our Token issuance evaluation metrics, here is a summary of private placement effectiveness:

(1) User Coverage: Poor—only investors participate, not actual users

(2) Compliance: Generally compliant

(3) Fundraising Performance: Usually effective in raising substantial amounts, though poor control over contribution granularity—all contributors are large-scale

ICO (Initial Coin Offering)

ICO (Initial Coin Offering) refers to the initial public issuance of digital tokens.

Originating from IPO (Initial Public Offering) in stock markets, ICO refers to blockchain projects issuing tokens to raise Bitcoin, Ethereum, or other mainstream cryptocurrencies. When a company seeks funding, it issues a fixed number of cryptographic tokens sold to participants. These tokens are typically exchanged for BTC, ETH, or sometimes fiat currencies.

ICO originated as a crowdfunding method unique to the blockchain sector. The first recorded ICO came from Mastercoin (now Omni), which announced a Bitcoin-denominated ICO on Bitcointalk in July 2013, distributing Mastercoin tokens to contributors. Essentially, this was a barter transaction—Bitcoin exchanged for project-specific tokens. Initially a community-driven activity among crypto enthusiasts, ICO gained broader acceptance as blockchain matured. Most ICOs were conducted using Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies.

ICO saw explosive growth after Ethereum enabled ERC20 token issuance on its platform. The largest ICO was EOS, which used a daily auction model over nearly a year to raise over $4 billion USD.

Advantages of ICO:

Provides a simple, convenient online fundraising method using cryptocurrencies. ICO effectively achieves both key objectives: fundraising and token distribution.

Problems with ICO:

Project Risk: Most ICO projects are in early stages, inherently risky and prone to failure. Like angel investing, ICOs expose investors to high early-stage risks and potential losses.

Financial Risks: Investors may face fraud or investment loss. Due to lack of regulation, some startups exploit market hype to fabricate projects and conduct fraudulent ICOs.

Regulatory and Legal Risks: Most ICOs collect BTC or ETH, operating in regulatory gray zones without clear legal frameworks. Since 2017, governments have increased scrutiny, but alternative IXO formats still serve similar functions.

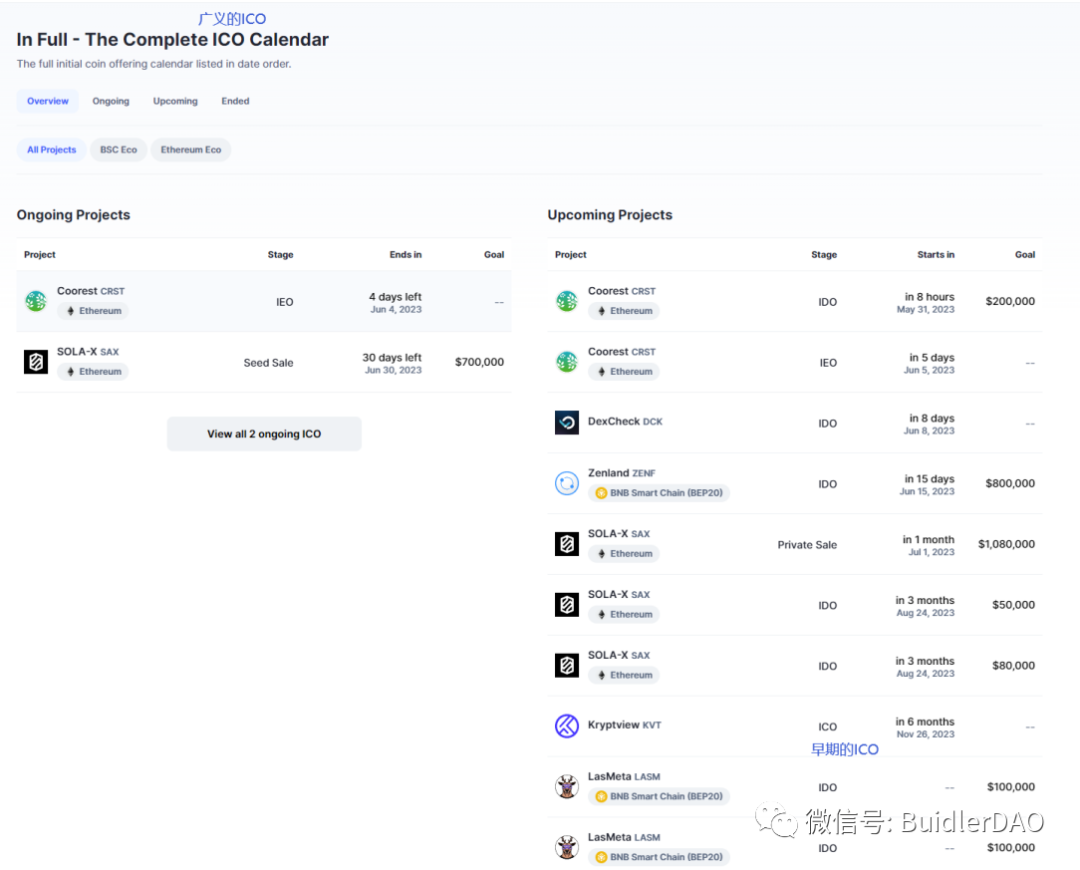

On CoinMarketCap today, ICO is broadly used to encompass all forms of initial token offerings, including IEO and IDO. As shown below: the top “ICO Calendar” is the broad sense of ICO, while “ICO” under Upcoming Projects refers specifically to the classic form described here.

Based on our evaluation metrics, here is a summary of ICO effectiveness:

(1) User Coverage: Broadest reach due to no entry barriers, but requires careful rule design to filter genuine users. Often attracts speculative investors rather than true product users. Combining with airdrops improves targeting.

(2) Compliance: Despite later adoption of KYC, ICOs are deemed illegal in most jurisdictions

(3) Fundraising Performance: Generally effective. If an ICO fails, other methods likely would too. Contribution size control remains poor—large contributions dominate.

Airdrop

Airdrop is a method of distributing digital tokens. Initially, Bitcoin mining was the sole way to obtain cryptocurrencies. Later, altcoins and forked coins began using airdrops—tokens sent freely to users’ addresses without requiring mining, purchase, or prior holdings. While unconditional giveaways occur, most airdrops follow specific rules—for instance, holding certain tokens. Rules are set by issuers, ranging from simple registration rewards to snapshot-based distributions.

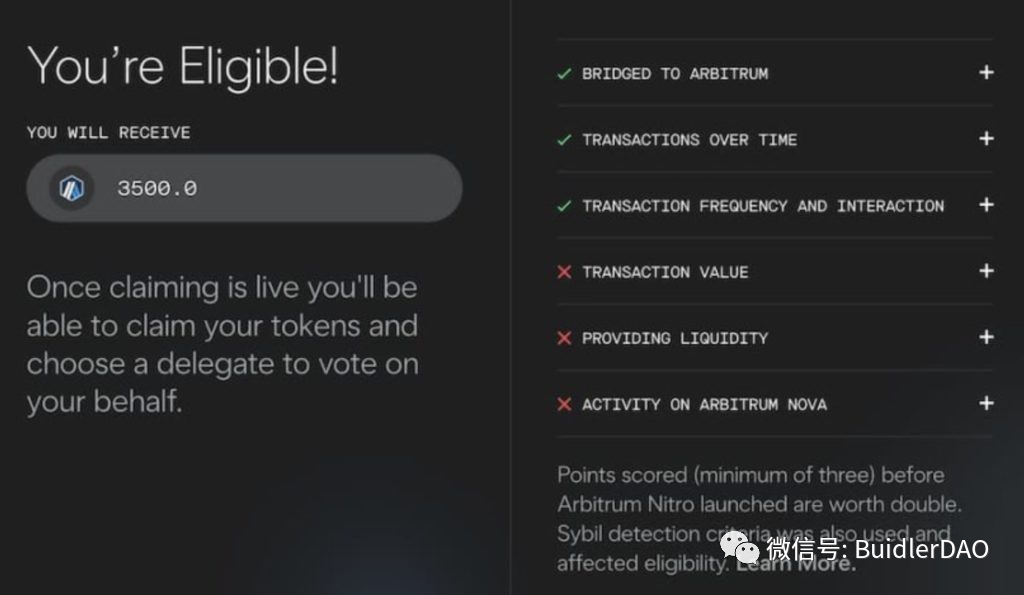

In early blockchain days, airdrop criteria were limited. But in the Web3 era, many projects conduct airdrops after achieving milestones, rewarding contributors or guiding users through tasks—e.g., Arbitrum’s airdrop design.

Advantages of Airdrop:

Distributes new tokens to desired user groups, promoting circulation and adoption. Since it doesn’t involve fundraising, airdrops typically avoid regulatory issues.

Enables targeted distribution to genuine users and incentivizes task completion.

Disadvantages of Airdrop:

Lacks fundraising capability—only facilitates token distribution.

Based on our evaluation metrics, here is a summary of Airdrop effectiveness:

-

User Coverage: Good reach when conditions are properly set

-

Compliance: Generally no compliance concerns

-

Fundraising Performance: Cannot raise funds, but allows precise allocation control

IEO (Initial Exchange Offering)

IEO – Initial Exchange Offering – Initial Cryptocurrency Exchange Launch

An IEO is a method for new projects to raise funds through cryptocurrency exchange platforms.

IEOs are typically supported by exchanges, so project teams must present robust proposals. In most cases, IEOs undergo rigorous review by the hosting exchange. In effect, the exchange backs approved IEOs with its commercial reputation.

With IEOs, potential investors can buy tokens before they’re listed. Registered users who complete KYC on the supporting exchange can purchase tokens ahead of public trading.

Advantages of IEO:

Compared to ICO, IEO offers clearer benefits. Tokens are immediately listed on exchanges, enhancing liquidity. Retail investors gain faster access. Project teams benefit from wider exposure—effectively reaching the entire exchange user base—expanding investor reach. For quality projects and early founders, IEO is not only a solid fundraising channel but also saves significant costs and effort associated with exchange listings, allowing focus on development and community building. For exchanges, IEO boosts trading volume and daily active users. Project fans bring new users and capital influx, some becoming long-term exchange customers. Such events prove more attractive than traditional marketing tactics like referral bonuses or trading competitions.

Disadvantages of IEO:

High issuance cost. Exchanges often charge listing fees, which can burden early-stage projects.

IEO imposes screening requirements, creating higher barriers for many projects.

Based on our evaluation metrics, here is a summary of IEO effectiveness:

-

User Coverage: Only reaches users interested in trading; struggles to attract true product angels. Best combined with airdrops.

-

Compliance: Typically ensured by the exchange

-

Fundraising Performance: Relatively strong—can raise substantial funds. However, pump-and-dump schemes and early exits by investors remain risks. Contribution size control is weak.

Compared to the original ICO, IEO expands the investor base and improves fundraising efficiency.

STO (Security Token Offering)

STO stands for Security Token Offering—issuing tokenized securities. A security is a valuable instrument representing ownership or creditor rights. The U.S. SEC considers any arrangement meeting the Howey Test as a security: "A contract, transaction or scheme whereby a person invests his money in a common enterprise and is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party." Broadly speaking, the SEC views any investment with profit expectations as a security.

STO transforms real-world financial assets or rights—such as company equity, debt, intellectual property, trust shares, or physical assets like gold and jewelry—into blockchain-based digital certificates. It digitizes real-world assets, rights, and services.

STO sits between IPO and ICO. Regulators aim to apply IPO-style oversight to digital token issuance. On one hand, STO acknowledges its securities nature and submits to national securities regulators. Though built on blockchain, technical updates allow alignment with regulatory frameworks. On the other hand, unlike the complex and time-consuming IPO process, STO leverages blockchain for efficient, streamlined issuance—similar to ICO.

Origins of STO

Persistent ICO failures shattered the blockchain myth, exposing scams, rug pulls, and Ponzi schemes. Fundamentally, these stemmed from ICOs lacking real assets or value—relying only on hype, visions, and meaningless consensus. Lack of direct regulation over ICOs and exchanges exacerbated the problem. STO, backed by real assets and embracing regulation, aims to break this cycle.

After observing blockchain-born tokens, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) decided to regulate them as securities—a move that initially seemed devastating to the crypto industry.

Yet the outcome was different: more countries followed suit, rolling out their own regulatory policies—even if definitions of STO varied. Markets gradually realized regulation wasn’t destruction but legitimization—enabling transparent, sustainable growth. Consequently, interest surged—from blockchain projects to traditional industries, from capital heavyweights to securities professionals and asset holders—all actively engaging or entering the space.

In a sense, amid identity confusion and controversy, regulatory intervention—like the sword of Damocles—has become a beacon cleansing reputational damage and guiding progress.

Initiated in the U.S., STO regulation has sparked global adoption, bringing clarity to an otherwise chaotic landscape.

Advantages of STO:

1. Intrinsic Value: STs are backed by real assets or revenue streams—e.g., company shares, profits, or real estate.

2. Automated Compliance & Instant Settlement: Approved by regulators, integrates automated KYC/AML, enabling real-time clearing and settlement.

3. Finer Ownership Division: Enables fractional ownership, lowering entry barriers for high-value investments like real estate or fine art.

4. Democratizing Venture Capital: Expands fundraising avenues.

5. Asset Interoperability: Standardized protocols simplify cross-asset and cross-currency transfers.

6. Enhanced Liquidity & Market Depth: Allows investment in illiquid assets without redemption worries. Market depth increases through:

-

Rising digital asset prices generating billions in new wealth reinvested into markets

-

Programmed market makers like Bancor improving liquidity for long-tail STs

-

Interoperability protocols facilitating cross-border asset flows

7. Reduced regulatory risk with enhanced due diligence. Supports regulatory exemptions, embedding KYC/AML rules into smart contracts for programmable compliance.

8. Potential reduction in asset circulation costs—lowering friction via smart-contract-based compliance and fund aggregation, on-chain accounting data, improved divisibility, and T+0 settlement.

9. Regulated by SEC under securities law—compliant and safer.

10. 24/7 trading availability.

Challenges of STO:

1. Strict transfer and sale restrictions. Unlike ERC-20 tokens—which anyone can freely send—security tokens cannot. Standards like Polymath’s ST-20 ensure tokens circulate only among KYC-verified individuals, limiting the tradable user base.

2. Cannot function as platform payment methods like utility tokens.

3. Significant regulatory hurdles exist for cross-platform ST circulation.

4. Excessive liquidity may cause extreme price volatility. STO could turn startups into de facto public companies overnight, with numerous token holders. Given the uncertainty and fluctuations typical of startups, such signals could trigger severe price swings.

5. STO innovation might merely shift risks to tail events.

6. Competition with traditional finance:

-

Competes with traditional financial products. From an investor’s view, despite greater transparency, being a security token (ST) doesn't automatically make it safer than utility tokens—it depends on the quality of the underlying asset, growth prospects, and financial health.

-

Competes for traditional financial capital. High-quality assets currently access far larger pools of capital and investors in traditional markets than in STO.

-

Competes with traditional financial institutions. Platforms offering securities fundraising for qualified investors already exist in the U.S.—from equity crowdfunding to real estate investment. For example, Fundrise allows accredited investors partial returns on real estate projects without tokens. Sharepost enables purchases of pre-IPO equity in startups using conventional tech infrastructure.

-

Competes with traditional financial environments. Traditional finance enjoys far more mature regulation and legal systems than STO.

7. Institutional investors make more rational decisions. Without retail participation in secondary markets, liquidity should be discounted, not premium—valuations generally unlikely to be higher.

8. Security tokens rely on financial intermediaries for risk assessment and pricing to better match assets with capital. STs require off-chain asset ownership and information to be linked on-chain, circulating as tokens under regulatory frameworks. Currently, ST value does not derive from on-chain activity or decentralized networks—it's merely regulated tokens mapping equity or debt, with little connection to DLT fundamentals.

STO attempts to manage cryptocurrency issuance using traditional IPO and securities regulation—but this poses great difficulty and challenges, as cryptocurrencies differ fundamentally from traditional securities. Regulatory policies must adapt accordingly.

Based on our evaluation metrics, here is a summary of STO effectiveness:

-

User Coverage: Restricted to users meeting regulatory criteria—fails to reach genuine product angels. Even crypto holders may be excluded.

-

Compliance: Compliant

-

Fundraising Performance: Generally weak due to restrictions. Poor control over contribution granularity.

Other IxO Models

IFO (Initial Fork Offering) – Initial Cryptocurrency Fork Launch

An IFO typically involves forking from major cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. The forked coin splits from the original blockchain following different rules—e.g., Bitcoin’s first fork created BCH (Bitcoin Cash). The fork inherits most of Bitcoin’s code and pre-fork data.

Forks are often paired with airdrops—distributing new coins to existing users, rewarding loyalty and accelerating new coin adoption.

How many fork-based models have succeeded? Ultimately, project sustainability depends on the team’s ongoing development. Teams using IFO often act speculatively, struggling to sustain long-term success.

IMO (Initial Miner Offering) – Initial Mining Machine Launch

IMO, or Initial Miner Offering, issues tokens through dedicated mining hardware.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News