Blockchain Gaming Explained: Types, Development Models, XR, Open Economies, and F2O

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Blockchain Gaming Explained: Types, Development Models, XR, Open Economies, and F2O

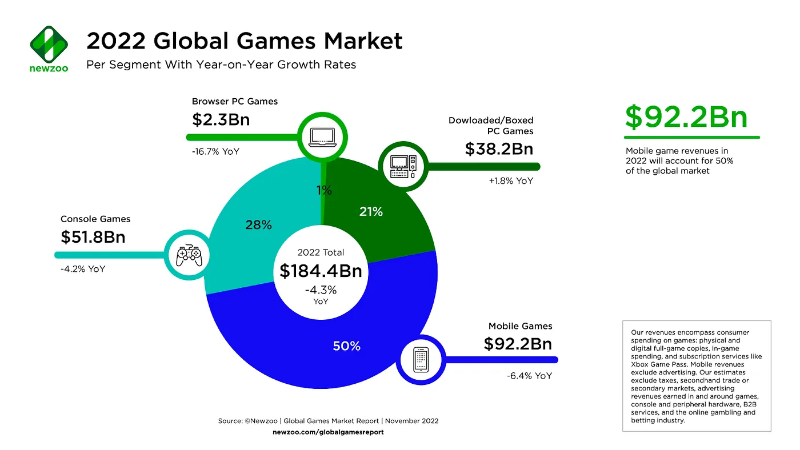

Since the invention of video games in 1958, the gaming industry has been growing steadily, with current market revenue reaching an impressive $185 billion annually.

Written by: Stanford Blockchain Review

Translated by: TechFlow

TechFlow is an official partner of the Stanford Blockchain Review and has been exclusively authorized to translate and republish this article.

Introduction

For me, gaming is a sustained injection of adrenaline and dopamine. Since the invention of video games in 1958, the gaming industry has steadily grown, with current market revenue reaching a staggering $185 billion annually.

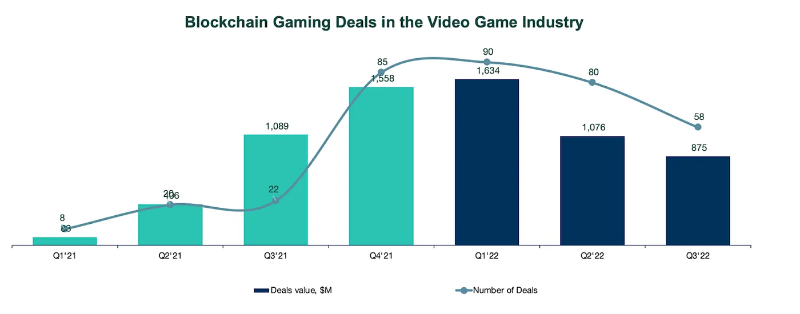

The gaming landscape is broad, encompassing arcade, console, browser-based, mobile, cloud, and augmented reality formats, giving players more diverse platform choices than ever. In recent years, we've also witnessed the rise of blockchain gaming. As of now, the blockchain gaming market is valued at approximately $4.6 billion, with projections indicating it could grow to $65.7 billion by 2027. This is a rapidly evolving category.

From Cryptokitties to Axie Infinity and the rollercoaster rise and fall of gaming guilds, capital floods in with trends and exits just as quickly when sentiment shifts.

Yet despite cycles of boom and bust, innovation inevitably emerges. I believe gaming can serve as a gateway for mass adoption of blockchain technology. There are still many unexplored frontiers ahead. In this article, I will analyze some of the key challenges and explore potential opportunities in developing new economic models for blockchain games, including content-driven/publisher-driven models, blockchain gaming XR, and the challenges of open economies.

Target Audience

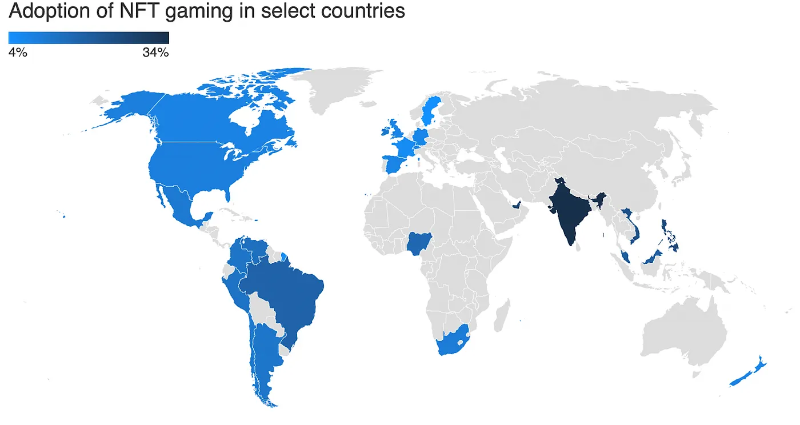

First, an important question: who exactly are "blockchain gamers"? While the industry is still nascent, the most active regions today are Southeast Asia, followed by Latin America and Africa.

Blockchain games are more popular in developing countries compared to developed ones, and their ARPU (average revenue per user) far exceeds that of traditional Web2 games (for example, Axie Infinity had >$100 ARPU).

According to a Newzoo report sampling the U.S., UK, and Indonesia, Indonesian players place greater emphasis on earning from games compared to players in other countries. I believe this reflects a fundamental difference between developed and developing nations—since income levels are generally higher in developed countries, the marginal utility of playing blockchain games for profit is likely lower there. This may also be one of the main reasons why blockchain gaming activity sharply declined during the bear market (as token prices fell, in-game earnings became less attractive than during bull markets).

In short, blockchain games currently appeal more to those seeking financial gain—by definition, value extractors—which puts pressure on game economies. To sustain these economies, we need more value creators than extractors. However, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa are not the largest gaming consumer markets. The top markets are the U.S., China, Japan, South Korea, and the UK.

It's worth considering that to attract players from these five major regions, games must be tailored accordingly, as they could help sustain in-game economies. In this sense, blockchain games need to shift focus toward fun and engagement. Although the U.S. and UK markets share similarities, China, Japan, and South Korea represent three entirely distinct gaming markets with different player behaviors and cultures, so localization may be a crucial strategy. I am excited about teams aiming to target these regions through customized marketing strategies.

For example, if targeting Japan, one might develop an anime-themed action RPG and focus marketing efforts on Twitter and Line; or if targeting India, prioritize mobile-based first-person shooters and collaborate primarily with YouTube influencers.

Types of Blockchain Games

Looking at the top 10 games by MAU (monthly active users), we see many collectible card games (CCGs) and strategy games. This trend may stem from four primary reasons:

-

These genres are more compatible with NFT trading and DeFi, attracting speculators—who have so far been the primary adopters of blockchain games.

-

They typically have shorter development cycles. Some early developers adopted a mindset of building lightweight/simple games first and leveraging experience to launch future titles.

-

These types suit browser-based platforms, often appealing to audiences less sensitive to time commitment—well aligned with CCGs and strategy games.

-

Current infrastructure limitations restrict playable categories (low throughput/high gas fees mean only assets with strong micro-management features are placed on-chain).

As infrastructure matures and talent flows into the industry, this trend may shift. The range of playable games could expand, and more portable device SDKs could bring blockchain games to mobile phones and consoles.

Greater choice in devices for playing blockchain games will lead to higher mass adoption. For most Web2 players, this could mean action RPGs (ARPGs), open-world games, hyper-casual games, and others taking center stage.

ARPGs usually require longer development cycles and more human resources to maintain patches and design engaging storylines. If properly designed, ARPGs can attract a core group of players with high time and monetary investment capacity. In short, ARPGs are genuinely fun (e.g., World of Warcraft) and inherently feature tradable equipment—making them ideal candidates for on-chain asset integration. Moreover, since many ARPGs already use gacha systems, moving these probabilistic events on-chain could increase transparency and eliminate opacity around "low drop rates."

Open-world games also tend to have long development cycles. By introducing nonlinear character progression and expansive exploration areas, they add extra layers of depth. These games are particularly popular in specific regions (e.g., more so in Asia than globally, especially in South Korea and Japan). Due to the presence of numerous probabilistic events (e.g., exploration zones, random enemy spawns), open-world games face even greater opacity issues—making them better suited than ARPGs for on-chain deployment.

My personal prediction is that hyper-casual games will become a popular blockchain gaming genre. Traditionally, these struggle with user retention due to shallow content. However, if fully deployed on-chain, blockchain’s composability enables potentially infinite UGC (user-generated content). Given the low development barriers typical of hyper-casual games, UGC would thrive here more than in other genres. Most importantly, stories could be created not only within a single game’s community but also by players from other communities entering or leaving the game.

However, it should be noted that commercial barriers exist for blockchain games expanding across devices (e.g., disputes over royalty splits with hardware providers, programmable smart contracts bypassing 30% app store fees), which are often overlooked.

I am excited about teams building open-world, ARPG, and hyper-casual games that focus on community and leverage crypto culture with potentially programmable royalties to reduce reliance on centralized marketplaces.

Content-Driven Studios vs Publisher Model

Historically, the highest-valued gaming companies have been publishers (e.g., Steam, Tencent)—and for good reason: content-driven games are often cyclical (e.g., Ubisoft), leading to unstable revenues because content is creativity-based. In the gaming industry, talent retention is also low (about 15.5% turnover rate), and given its creative nature, losing key designers from content studios can be devastating.

As companies grow and institutionalize, employees and shareholders typically prefer more predictable income streams, allowing publishers to scale more effectively. Yet while the publisher model appears strong on paper, it usually requires substantial startup capital and expertise in distribution channels, marketing, and partial community management—skills accumulated over years of industry experience. Distribution channels, network effects, and traffic moats built by publishers are significant, resulting in limited competition at the top tier of Web2 gaming publishing. (People don’t just go to Steam because their favorite games are released there—they buy games and discover new ones on Steam.)

In Web3, a clear dominant publishing platform has yet to emerge. Most studios self-publish, meaning the publishing space remains competitive but unsaturated. When deciding whether to allow permissionless listing of games, platforms must balance launch efficiency against content quality.

On the other hand, game development studios require less capital and can rely on distribution channels like Steam and Origin. However, raising funds before a prototype is built makes team background and track record critically important. This pushes many newcomers and less fundraising-capable talents toward the indie developer market—where development speed and quality are often slower/lower.

This is one area where AIGC can significantly improve things, helping developers save time and cost in designing game content (from graphics to NPC design to audio), thereby opening up investment opportunities. This is especially meaningful for Web3 game studios, most of which are small, single-digit teams.

In my view, visionary studios should aim to create blockbuster titles and eventually transition into publishers.

-

In Web2, Valve created hit games like Half-Life before launching Steam;

-

In Web3, Sky Mavis (with Ronin Chain aiming to attract other games beyond Axie) follows a similar path.

This requires studios to deeply understand games, design capabilities, and overcome challenges such as open economy design and blockchain selection—a significantly harder path.

However, with the rise of AIGC, I expect content creation costs to decrease dramatically over time, unleashing creativity among independent studios and small teams and injecting more content into the ecosystem. In recent years, true 0-to-1 innovation has been rare, as early-stage VCs favored fewer content studios. But with easier content creation methods emerging, this trend may reverse.

I’m excited about teams with strong marketing and business development backgrounds building publishing platforms and offering user-friendly onboarding features like easy wallet integration. As a clear winner emerges, leadership in this space may gradually erode. I'm equally excited about content studios committed to fully blockchain-native game development, where leadership advantages are less likely to decay.

Successful content development can build intellectual property (IP) tied to merchandise and accessories—potentially combinable with the XR concepts discussed below.

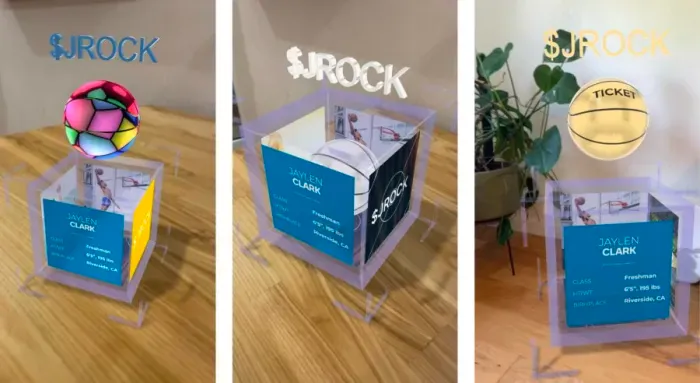

XR (Extended Reality) and Blockchain Game Decorations

This represents a fusion of virtual and physical experiences. Imagine your custom-designed NFT item from the metaverse now projected into real life via smartphone or smart glasses in 3D—you love it so much that after some thought, you decide to 3D print it.

Your 3D item's metadata is encrypted (e.g., using asymmetric encryption for angles, rotation, dimensions), hidden in the metaverse to prevent scraping, and only released when a printer verifies ownership (e.g., via wallet address). Each printed item is unique and belongs solely to you—even if others can view your NFT in the metaverse, they can never own the physical version like you do.

You could even maintain anonymous owner/artist identity by using zero-knowledge (ZK)-based ownership proofs (proving ownership without revealing identity) and validator networks to verify that manufacturing/printing was completed correctly.

If printing occurs remotely, decentralized tracking systems (e.g., VeChain’s solution) can monitor location to ensure proper delivery. You could even set up validator networks to ensure printing conditions are maintained throughout transit.

Challenges of Open Economies

Game economy determines game longevity. Achieving sustainable economics is inherently difficult, requiring a balance between value extractors and creators to maintain economic health. Guilds like Yield Guild Games ("YGG") are nothing new—in 2004, large guilds in RPGs like MIR3 were already collecting gear, putting strain on in-game economies.

In Web2, game designers typically act as both government and central bank, regulating the economy to keep in-game items fluctuating within healthy price ranges and improving player retention. Studios can control the economy because Web2 games operate in closed loops—each game functions like an isolated nation with little cross-trade.

However, Web3 is inherently open, meaning studios can only function as central banks and governments within their own games—not the entire world. With multiple interacting game economies (e.g., capital flowing from Decentraland to Sandbox), we may need to consider additional “foreign exchange” systems—how items trade between different economies. Just as gold served under the Bretton Woods system, ETH/stablecoins have become mediums for most game asset transactions. Will we ever see direct game-to-game asset swaps? I think this is unlikely, as increasing on-chain game assets may exacerbate liquidity fragmentation.

Game studios now need to account for additional factors like lending (outflows), borrowing (inflows), and leverage (e.g., leveraged purchases of in-game items), all of which could destabilize game economies. Designers must therefore spend more effort adapting in-game economies to external flows occurring in Web3.

The dual-token model (governance + utility tokens) is currently popular in blockchain games, but careful attention must be paid to where sinks and faucets exist in the economy—especially utility tokens. Sinks impact value creation similarly to how faucets affect value extraction. Overall, the more sinks a game has, the stronger its economy is likely to remain.

Teams should also consider taking a stronger central bank role in early game stages (when player count is below N), directly or indirectly influencing token issuance through policy, then gradually transferring power to DAOs as player numbers grow. Algorithmic policies (e.g., increasing incentives for player participation when outflows are excessive) should also be considered under community proposals.

Pre-minted NFTs represent another single point of failure. Many studios use them for funding, but they create early-holder problems that can affect game development. You end up with a mixed audience—one group eager to extract maximum value upon launch or positive news, and another genuinely interested in trying and supporting the game. This makes stakeholder alignment extremely challenging, lowering overall player retention (similar issues occur with platform launches).

I’m excited about teams building scalable stress-testing analytics software capable of ingesting and analyzing common on-chain and off-chain data. While each game economy differs, many core metrics should remain consistent across games (e.g., active player inflows/outflows, fiat-denominated fund flows). In other cases, studios may require specialized economic advisors/designers/asset managers. Additionally, minimizing tradable assets early on may be wise—more assets mean more economic layers, making control harder.

F2O Game Economy?

This term originated from Limit Break, whose Digi Daigaku Genesis airdrop garnered massive attention across platforms. Digi Daigaku opted for a stealth launch with free minting on August 9, revealing no information—a stark contrast to traditional NFT launches. Limit Break is the company behind Digi Daigaku. On August 29, Limit Break announced a $200 million funding round. With this news, Digi Daigaku’s floor price surpassed 15 ETH.

Genesis holders receive future airdrops, enabling a gacha-like system. If subsequent airdrops unlock content, unique powers, or special items, this helps boost user retention. Users worry less about rug pulls, are more likely to engage emotionally with the game rather than calculating returns, reach broader audiences more easily, and are more inclined to continue development (as royalties may remain a primary revenue stream for studios).

However, if future airdrops hold zero value, Genesis theoretically becomes worthless too. High royalty rates could also hinder NFT circulation. Smaller studios lacking Limit Break’s funding may struggle to gain visibility due to limited marketing budgets, thus failing to benefit from the F2O model. Conversely, if the number of F2O games increases in the market, user acquisition costs could drop to near-zero.

So far, F2O resembles the F2P market, but I don’t believe the two will converge. Because Genesis NFT collections have limited supply, restricting game testing to specific NFT holders may give F2O an advantage in controlling the pace of player base expansion. How game designers select participants for free mints (based on community activity, skill levels in similar games, etc.) is also a critical decision.

Overall, F2O seems better suited for well-funded studios planning to implement gacha mechanics and with clear monetization strategies for traditional players. But the concept is rapidly evolving, and more suitable use cases may soon emerge. For now, I remain cautiously neutral, having not yet seen F2O as the definitive solution for blockchain game economies.

Conclusion

Web3 game economies are complex, yet full of potential. Before creating stakeholder conflicts, developers should carefully consider their target audience and monetization methods, and boldly experiment with new incentive models—because the risk/reward ratio is asymmetric.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News