How to build a fake decentralized cross-chain protocol?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

How to build a fake decentralized cross-chain protocol?

"Great designs appear very simple, but the process of designing them is actually extremely complex."

Author: Kang Shuiyue, Founder of Fox Tech and Way Network, Chairman of Danyang Investment

Adam Back (leader of the Bitcoin Core development team and CEO of BlockStream) once said something that left a deep impression on me: "Great designs appear extremely simple, but the process of designing them is actually extremely complex." However, not every product design that appears simple can be considered great—LayerZero being a case in point.

Cross-chain protocols seem safe until an incident occurs—and when it does happen, it’s usually catastrophic. Looking at the financial losses caused by security incidents across various blockchains over the past two years, cross-chain protocols rank first in terms of total damage.

The importance and urgency of solving cross-chain protocol security issues surpass even Ethereum scaling solutions. Interoperability among cross-chain protocols is an intrinsic requirement for Web3 to form a true network. These protocols often raise substantial funding, and their TVL (Total Value Locked) and transaction volumes continue to grow under real demand. Yet due to low public awareness, users are unable to distinguish between different security levels of these cross-chain protocols.

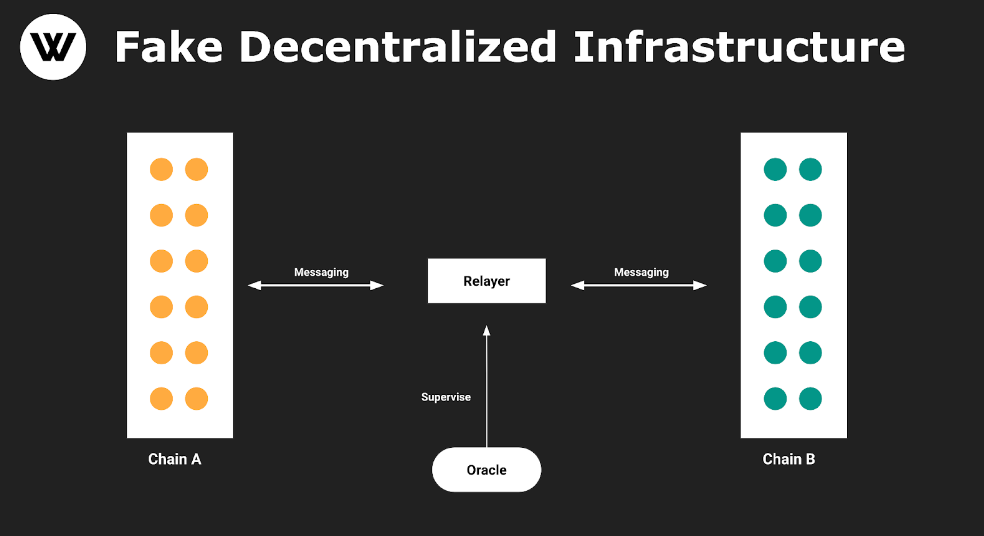

Let’s examine a product architecture: Communication between Chain A and Chain B is executed by a Relayer, with an Oracle overseeing the Relayer.

One advantage of this architecture is eliminating the need for traditional consensus algorithms and dozens of node validations via a third chain (which typically doesn’t host dApps). This enables end users to enjoy a “fast cross-chain” experience. Due to its lightweight structure and minimal codebase—with existing Oracle solutions like Chainlink readily available—projects based on this model can launch quickly. But they’re also easily replicated, meaning technical barriers are essentially zero.

Figure 1: Basic version of a pseudo-decentralized cross-chain protocol

This architecture has at least two critical flaws:

1. LayerZero reduces validation from dozens of nodes to just a single Oracle, significantly weakening security.

2. After simplifying to single-point verification, one must assume the Relayer and Oracle operate independently. However, this trust assumption cannot hold indefinitely. It’s not truly crypto-native and fails to prevent collusion between the two parties.

This is precisely the fundamental model adopted by LayerZero. As a so-called “ultra-light” cross-chain solution focused on independent security, it only handles message relaying and bears no responsibility—for either capability or liability—for application-level security.

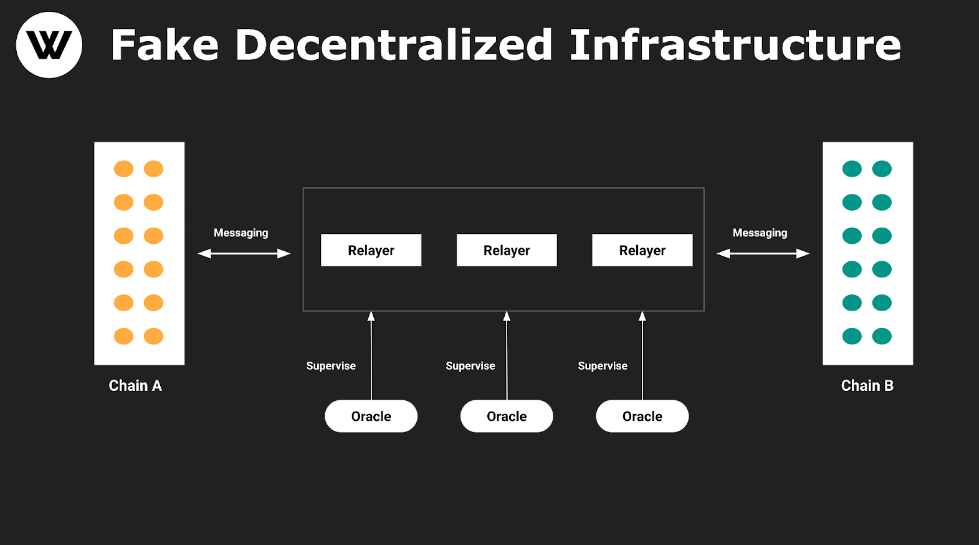

Then, what if we open up the Relayer role, allowing anyone to run a relay node—would that solve the above issues?

Figure 2 expands upon Figure 1 by increasing the number of participants. First, decentralization isn't defined merely by having more operators or permissionless access—that's called Permissionless. Demand-side openness has always been permissionless. Making the supply side permissionless isn't revolutionary—it reflects market dynamics rather than enhancing product security. In LayerZero, the Relayer is fundamentally just an intermediary forwarding messages, no different in essence from the Oracle—a Trusted Third Party. Attempting to improve cross-chain security by increasing trusted entities from one to thirty is futile. It doesn’t change the core nature of the product and introduces new risks.

Figure 2: Advanced version of a pseudo-decentralized cross-chain protocol

If a cross-chain token project allows modification of configured LayerZero nodes, attackers could replace them with their own malicious “LayerZero” nodes and forge arbitrary messages. Ultimately, projects using LayerZero face severe security vulnerabilities—and such problems become worse in more complex scenarios. In large systems, replacing just one component may trigger a chain reaction.

LayerZero itself lacks the capability to resolve this issue. In the event of a security breach, LayerZero naturally shifts responsibility onto external applications. End users must individually assess the safety of each project using LayerZero, which discourages user-centric projects from integrating with LayerZero to avoid contamination by malicious actors within the same ecosystem. As a result, building a healthy ecosystem becomes significantly harder.

If Layer0 cannot share security like Layer1 or Layer2, then it cannot be called Infrastructure. The reason infrastructure is “fundamental” is because it provides shared security. If a project claims to be Infrastructure, it should offer consistent security guarantees across all its ecosystem projects—meaning all ecosystem projects share the underlying infrastructure’s security.

Therefore, to be precise, LayerZero is not infrastructure, but middleware. Application developers integrating this Middleware SDK/API are indeed free to define their own security policies.

On January 5, 2023, the L2BEAT team published an article titled *Circumventing Layer Zero: Why Isolated Security is No Security*, arguing that assuming app owners (or private key holders) won’t act maliciously is incorrect. For example, “Bad Bob” gains access to LayerZero configuration and changes the default Oracle and Relayer components to ones he controls, tricking a smart contract on Ethereum into transferring all of “Good Alice”’s tokens to him. Original link

On January 31, 2023, the Nomad team pointed out that LayerZero’s Relayer has two critical vulnerabilities. Currently operating under a two-party multisig setup, these flaws can only be exploited by insiders or known team members. The first allows sending fraudulent messages from the LayerZero multisig; the second allows modifying messages after both the Oracle and multisig have signed them—both leading to potential theft of all user funds. Original link

When dazzled by flashy appearances, try returning to first principles.

On October 31, 2008, the Bitcoin whitepaper was released. On January 3, 2009, the BTC genesis block was mined. The abstract of the whitepaper “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” reads:

Abstract. A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. The network timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain of hash-based proof-of-work, forming a record that cannot be changed without redoing the proof-of-work. The longest chain not only serves as proof of the sequence of events witnessed, but proof that it came from the largest pool of CPU power. As long as a majority of CPU power is controlled by nodes that are not cooperating to attack the network, they'll generate the longest chain and outpace attackers. The network itself requires minimal structure. Messages are broadcast on a best effort basis, and nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone.

Chinese translation of the abstract:

A purely peer-to-peer electronic cash system would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still needed to prevent double spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. The network timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain of hash-based proof-of-work, forming a record that cannot be changed unless the proof-of-work is redone. The longest chain not only serves as evidence of the sequence of events observed, but also proves it originated from the largest pool of CPU power. As long as most CPU power is controlled by nodes that aren't colluding to attack the network, they will generate the longest chain and outpace attackers. The network itself requires minimal structure. Messages are broadcast on a best-effort basis, and nodes can freely leave and rejoin the network, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof of what occurred during their absence.

From this historically significant paper—especially from this abstract—people later distilled what became widely known as the “Satoshi Consensus,” whose core principle is eliminating any Trusted Third Party, achieving trustlessness and decentralization. Here, the term “center” refers precisely to a Trusted Third Party. Cross-chain communication protocols are, at their essence, peer-to-peer systems—enabling direct transfers from one party on Chain A to another on Chain B, without relying on any trusted intermediary.

The “Satoshi Consensus” with Decentralized and Trustless characteristics has become the shared goal for all subsequent infrastructure developers. Indeed, any cross-chain protocol failing to meet the criteria of “Satoshi Consensus” is a pseudo-decentralized cross-chain protocol and should not use advanced terms like Decentralized or Trustless to describe its features. Yet LayerZero markets itself as an omnichain communication, interoperability, decentralized infrastructure. According to its official description: "LayerZero is an omnichain interoperability protocol designed for lightweight message passing across chains. LayerZero provides authentic and guaranteed message delivery with configurable trustlessness."

In reality, LayerZero requires both the Relayer and Oracle to not collude maliciously, demands users trust the developers building applications on LayerZero as trusted third parties, and pre-designates privileged entities involved in the “multisig.” Meanwhile, throughout its entire cross-chain process, no fraud proofs or validity proofs are generated, let alone posted on-chain for verification. Therefore, LayerZero fundamentally fails to satisfy the “Satoshi Consensus” and is neither Decentralized nor Trustless.

After the L2BEAT and Nomad teams published well-intentioned critiques from a vulnerability-discovery perspective, LayerZero responded with denial—followed by further denial. Many digital currencies existed before Bitcoin, yet they all failed because they couldn’t achieve decentralization, resistance to attacks, and intrinsic value. The same applies to cross-chain protocols: no matter how much funding they raise, how much traffic they attract, or how “pure” their pedigree appears—if the product cannot deliver Real Decentralized Security, it will likely collapse due to insufficient resilience against attacks.

Once, a friend whose position should have aligned closely with LayerZero asked me: “If LayerZero wanted to upgrade their cross-chain protocol using zero-knowledge proofs like Way Network does, how difficult would that be, and what obstacles might they face?” It’s an intriguing question—the crux being they don’t believe they have a problem.

As for how to build a truly decentralized cross-chain protocol, please refer to my previous article: “Why Use Zero-Knowledge Proofs to Develop Cross-Chain Protocols?”

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News