Will Web3 belong to Indians sooner or later?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Will Web3 belong to Indians sooner or later?

When an organization hires one Indian, a bunch of Indians will soon follow.

By: 0xmin

Recently, Indians have become stars on the global stage.

After dominating Silicon Valley, Indians have now taken over the UK. At 42, Sunak became the first Indian-origin Prime Minister of Britain, with ethnic Indian elites continuously breaking into mainstream circles. Once colonized by the British, India now sees its descendants leading the UK—fate has turned full circle, and 10 Downing Street is beginning to exude a strong aroma of curry.

Previously, Silicon Valley had already become an Indian stronghold, where top-tier Chinese workaholics once ruled Big Tech.

Besides Apple, CEOs of major giants including Alphabet (Google’s parent), Microsoft, IBM, PepsiCo, Adobe, and SoftBank Vision Fund are all Indians. Combined with their unique “clan culture,” where one brings in another, Indian immigrants have built extensive networks that now permeate across industries.

In the emerging field of Web3, Indian influence is also rapidly rising: Polygon—the shining star from India—has evolved from a Bangalore-based startup into a globally recognized L1/L2 chain, shedding its "curry flavor" along the way and leveraging powerful business development capabilities to rank among the world's top blockchain platforms.

Meanwhile, Indian diasporas are following in the footsteps of their Silicon Valley predecessors, clustering within top Web3 institutions. Kanav Kariya rose from intern to President at Jump Crypto; Dragonfly partner Haseeb Qureshi continues to expand his career footprint... In short, once there’s one Indian at an organization, more will quickly follow.

What advantages do Indians have in Web3, and how do they differ from Chinese entrepreneurs? To explore this question, we interviewed multiple VCs and founders about their views on the Indian market and people.

The Talent of Articulating What You’ve Done

In interviews, nearly every respondent mentioned Indians’ “performance skills.” They excel at self-promotion, use exaggerated expressions, and speak in highly persuasive ways, easily drawing listeners into their narratives. Or put simply, they’re great at “bragging”: when Chinese people achieve 100, they typically say they’ve done 70, while Indians can confidently claim they’ve achieved 200.

In fact, this isn’t necessarily a flaw—it’s a trait that Chinese professionals should learn. Whether climbing the corporate ladder or starting businesses, modesty and reserve aren’t always beneficial, especially in a narrative-driven ecosystem like Web3.

A woman who studied long-term in the UK noted that whether seeking partners or jobs, Indians tend to be bold and proactive—even rejection doesn’t faze them. They seem devoid of any sense of “shame.” In Yang Li’s words: “Why are they so ordinary, yet so confident?”

Chinese men, even when exceptionally talented, are generally low-key and reserved, carrying greater “shame” or self-consciousness. To some extent, this reflects deeper cultural differences between China and India. Under strong Confucian influence, East Asian cultures emphasize humility, harmony, and stability. By contrast, Indians display far greater confidence—even what might be called blind confidence.

A Key Tool for Bridging Cultural Gaps

Another fundamental yet often overlooked strength enabling Indians to break through: language advantage.

Although many perceive Indian English as heavily accented and hard to understand (“curry-flavored”), Americans generally view it as just a normal accent with no real communication barrier. Thus, whether entrepreneurs or executives, Indians can chat effortlessly with Americans and casually drop slang.

When Chinese entrepreneurs decide to go global, their first challenge is often “not fluent enough in English.” Even those confident in spoken English frequently face cultural gaps—conversations fail to connect, ending awkwardly. This has created a unique demand in the Chinese market: financial advisors (FAs). Chinese founders often need an intermediary to introduce them to VCs, ideally someone acting as an agent to handle all communications with U.S. investors. But to Silicon Valley, this seems strange.

From an internationalization standpoint, Indians possess inherent advantages in both educational traditions and cultural DNA.

Band Together, Then Band Together Again

Group solidarity is another defining trait of Indians.

Once one Indian rises to power, others soon follow—even if it means promoting relatives or allies, which they do without guilt. After all, shared ethnicity and cultural background reduce trust and communication costs, facilitating smoother operations.

But this phenomenon is rare among overseas Chinese communities. Li Kaifu, who long served as a senior executive in the U.S., deeply understands this issue.

In past interviews, Li Kaifu noted that Indians are more united and better at self-promotion (more outgoing and expressive), allowing them to integrate more smoothly into American culture. In contrast, Chinese employees in large U.S. companies lack unity, forming separate cliques that operate independently—even engaging in infighting among themselves.

Huang Zhengyu, former Managing Director at Intel, echoed this sentiment when asked why few Chinese in America reach executive roles: Chinese people have a small but persistent problem—factionalism.

Compared to “uniting against external threats,” Chinese seem to prefer “internal stability before external action.” Sometimes, internal politics take precedence over collective progress. After securing their seat at the table, many tend to shut the door behind them, ensuring they remain the last beneficiary—a classic case of “professionals belittle each other.”

Therefore, in the relatively underrepresented Chinese presence in crypto, we call for greater “unity,” especially among overseas Chinese who should support and collaborate with one another.

However, there’s also an objective factor: for Indians in developed countries like the U.S., there’s often no fallback option. They must push forward with unwavering determination—“not returning until victory is won.” As a result, many seasoned Indians appear intense and driven, with a fierce hunger for success, wealth, and promotion.

By comparison, Chinese have more fallback options—if the West fails, the East still shines. Overseas Chinese are adept at navigating both China and the U.S. simultaneously, capitalizing on arbitrage opportunities. For example, figures like Qi Lu and Ning Yan returned to China in pursuit of better opportunities, whereas Indians often cannot “return,” leaving them no choice but to press ahead in the U.S.

A friend building a startup in India remarked that India’s elite class and average citizens are almost different species. The Indian elite are both intelligent and hardworking, combining Eastern emotional subtlety with Western expressive ability. Their achievements abroad are hardly surprising—they place high value on business education, and their academic systems seamlessly align with Western standards, making them highly competitive.

Bright Future or Hidden Pitfalls?

When discussing emerging markets like India, Africa, and Latin America, public opinion often splits. That is, Silicon Valley investors who’ve never visited India or Africa endlessly cite data to argue these regions are the future, brimming with optimism; meanwhile, those actually operating on the ground tend to be more pessimistic, seeing less rosy prospects.

In terms of market potential, both Web2 and Web3 sectors regard India as a “hot investment thesis.” A Chinese entrepreneur active in the Indian market noted that while per-customer spending and willingness to pay are low, massive inflows of foreign capital have heated up the primary market: “Whether traditional internet or Web3, Indian startups aren’t cheap anymore”.

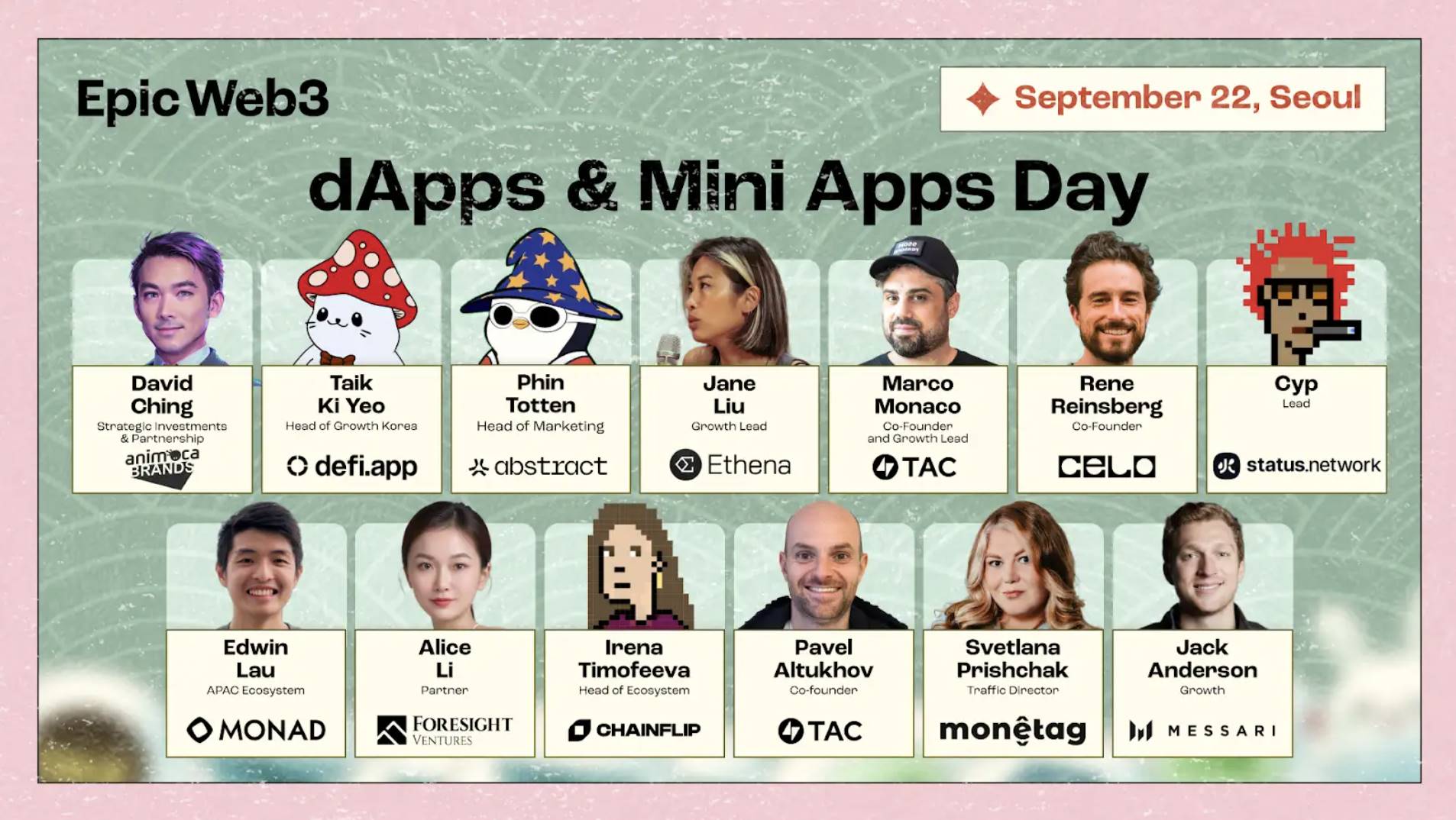

In Web3, Sequoia Capital, Lightspeed, Sino Global, Binance Labs, Cypher Capital, Coinbase Ventures, and others have expressed strong interest and placed bets on India. Massive population, engineering talent dividend, user demand driven by foreign exchange controls… all contribute.

We acknowledge India’s potential to become a Web3 hotspot, but the key risk remains policy stability and continuity. The Reserve Bank of India has voiced opposition to crypto; India’s reputation as the “graveyard of multinational corporations”; and cases of frozen accounts—all raise concerns. Previously, India investigated Chinese firms like VIVO and Xiaomi over alleged tax evasion and froze bank accounts of several companies.

Data shows that over the past eight years, more than 2,000 multinational corporations have exited India. Honor announced its withdrawal due to various reasons. Foreign enterprises including UK telecom giant Vodafone, IBM from the U.S., and French spirits producer Pernod Ricard faced sanctions and ultimately left the Indian market.

Considering all factors, some investors now adopt a stance of “cautious optimism”: “Beyond breakout projects like Polygon, India itself lacks many high-quality startups. However, I believe in Indians and the Indian diaspora—they’ll shine in Web3 as top-tier professionals.”

Overall, whether in Web2 or Web3, Indians have emerged as a force to be reckoned with—one that Chinese going global should study. Their racial advantages and innate traits may be deeply ingrained, but Chinese strengths are equally real and tangible. For Chinese people, becoming more confident, more united, and more open remains an enduring mission we must relentlessly pursue.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News