The Post-Merge Era: Ethereum's Rebirth Through a New Consensus

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Post-Merge Era: Ethereum's Rebirth Through a New Consensus

The Merge is merely the first step into the PoS era. Ethereum still faces significant challenges, including validator centralization, scalability, and the Lazy Validator Problem, all of which continue to constrain application proliferation and secure scaling of the Ethereum network.

By | Frank Fan @Arcane Labs

0xCryptolee @Arcane Labs

Edited by | Charles @Arcane Labs

Ethereum has undergone a historic upgrade, entering a new phase of development. After The Merge, Ethereum will continue advancing toward scalability and decentralization. The Merge is merely the first step into the PoS era. Ethereum still faces significant challenges—validator centralization, scalability, and the Lazy Validator Problem—that continue to constrain application growth and the secure scaling of Ethereum. This article begins with The Merge, analyzing the consensus algorithm adopted under PoS, focusing on how DVT technology can address single-point risks for validators. We aim to help industry practitioners analyze Ethereum’s current issues and future opportunities. Readers are advised to have a foundational understanding of Ethereum before reading this piece.

#1 The Merge

1.1 Background

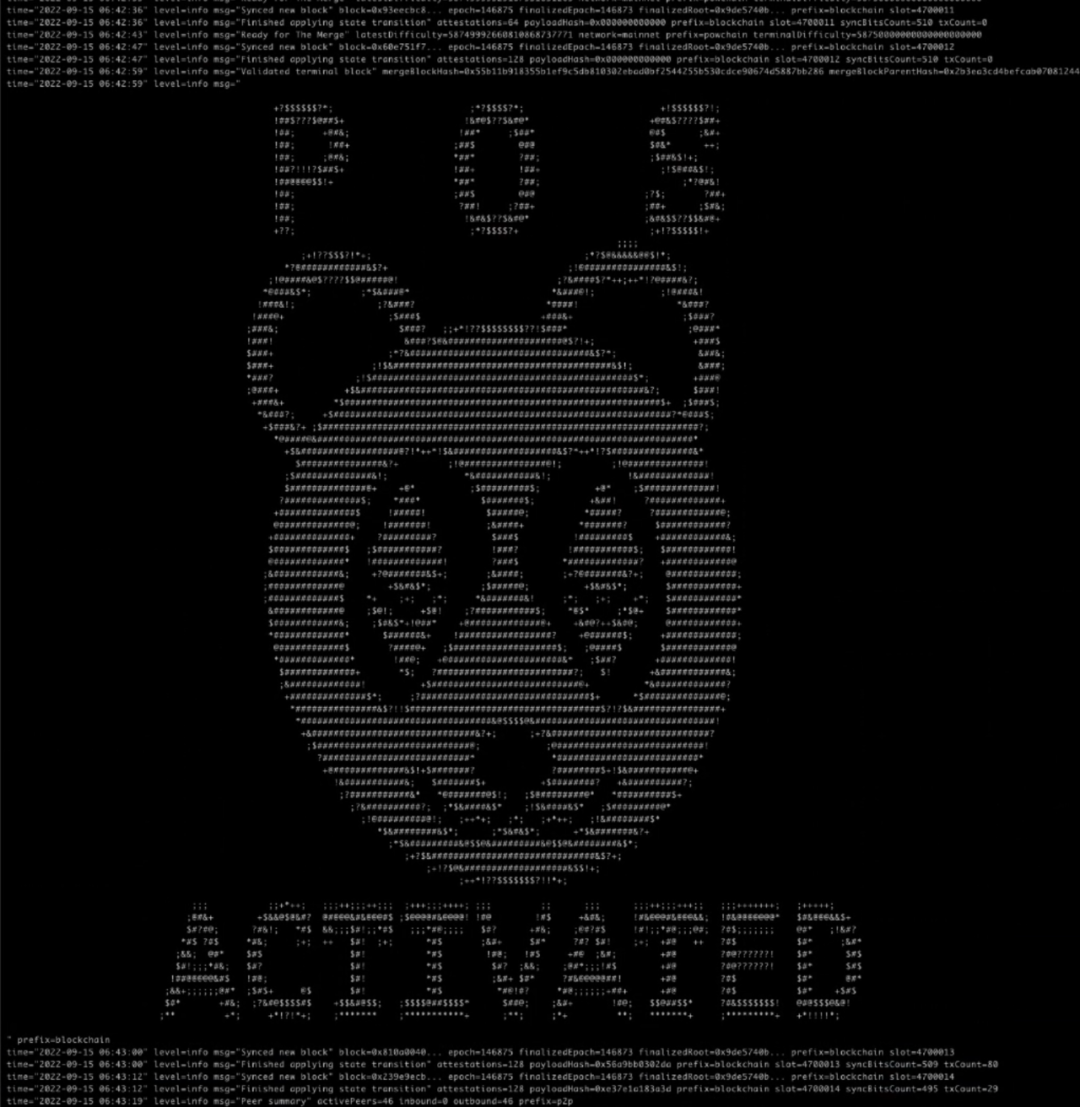

The Merge represents the largest technical upgrade in Ethereum’s history, successfully merging the Execution Layer and Consensus Layer on September 15, 2022. The most significant change was transitioning Ethereum’s consensus mechanism from PoW to PoS.

Figure 1: The Merge

In addition, post-merge, Ethereum’s energy consumption decreased by nearly 99.95%. According to Vitalik Buterin’s tweet, The Merge reduced global electricity usage by 0.2%.

Figure 2: Vitalik’s View on Ethereum Energy Consumption Post-Merge

1.2 Changes Brought by The Merge

-

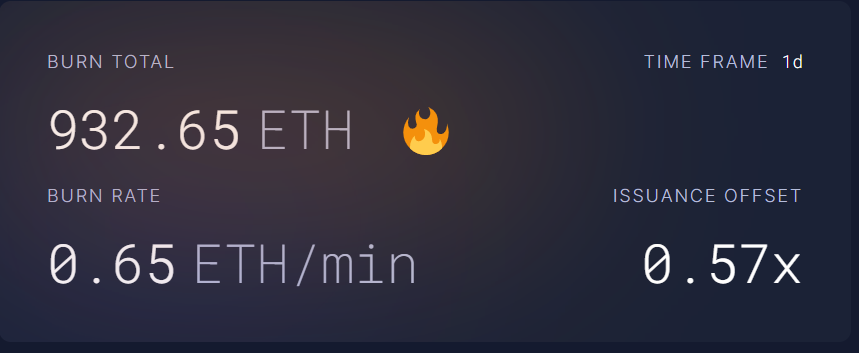

Token Issuance:ETH issuance under PoW has ceased. New ETH is now generated solely through PoS block production, reducing Ethereum’s inflation rate. When base fees exceed 15 gwei, Ethereum even enters deflationary mode.

Figure 3: Total Burn Post-Merge

-

Staking Rewards:Validator income from gas fees and MEV increases staking yield to 5–7% in ETH terms.

Figure 4: Rocket Pool Staking Yield

-

Withdrawals:Post-merge, staked ETH cannot be immediately withdrawn. Withdrawal functionality will be enabled via the Shanghai upgrade. To prevent mass withdrawals, limits on withdrawal amounts and frequency will apply. Thus, widespread selling upon withdrawal activation is unlikely. For details, see EIP-4895: Beacon chain push withdrawals as operations.

-

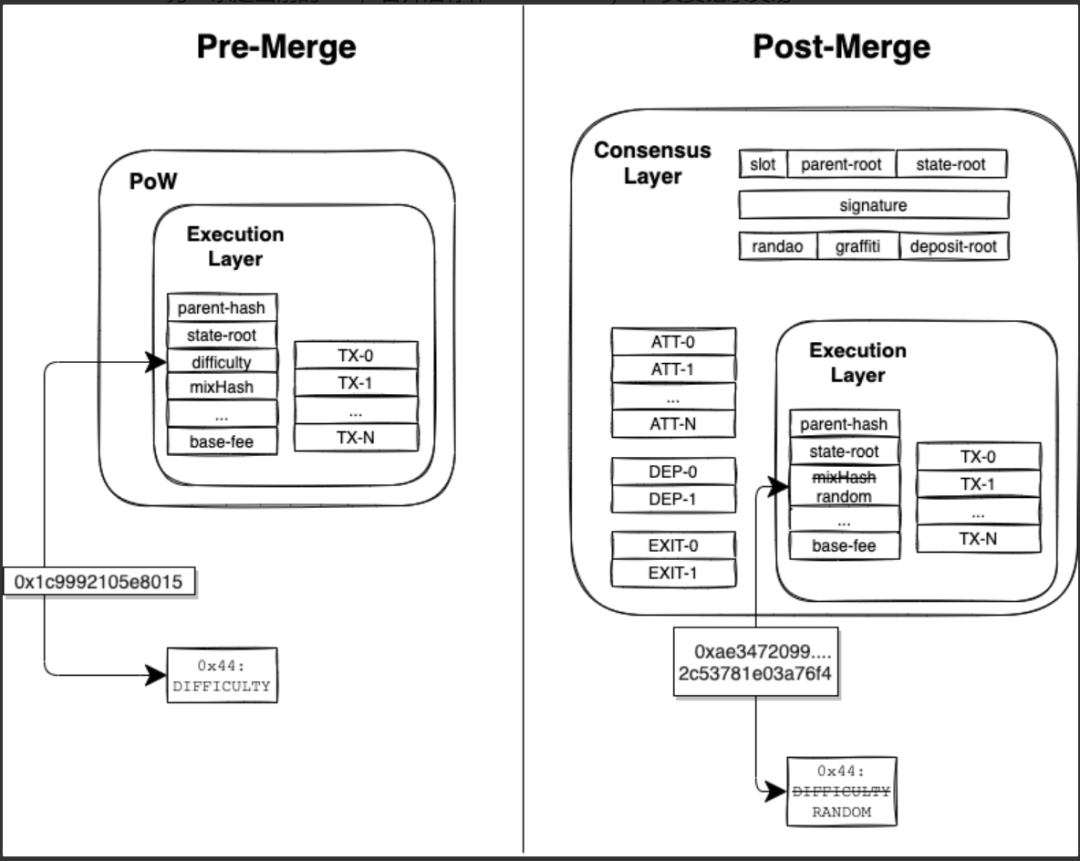

Data Structure Changes:Consensus Blocks now contain the hash of Execution Blocks. Parameters related to PoW in Execution Blocks are no longer valid. The mixHash field records Ethereum’s native RANDAO randomness, accessible by the EVM, allowing developers to directly use this random number in smart contracts.

Figure 5: Data Structure Changes Post-Merge

-

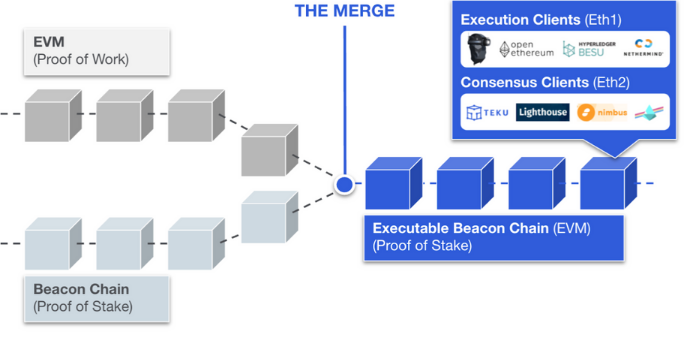

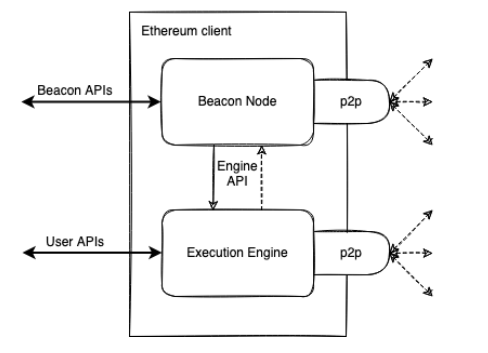

Consensus Replacement:PoW is replaced by PoS. Miners’ roles are taken over by validators. Two chains now coexist, requiring two client nodes to run simultaneously: Execution Layer Client (EL) and Consensus Layer Client (CL).

Figure 6: Ethereum Clients Post-Merge

After switching to PoS, Ethereum’s algorithm changed from Ethash to Casper FFG (Gasper). Compared to previous algorithms, Gasper is more energy-efficient, eliminating the need for specialized mining hardware to compute difficulty. Instead, blocks are proposed randomly. Let’s dive deeper into Ethereum’s consensus mechanism and block production!

#2Gasper

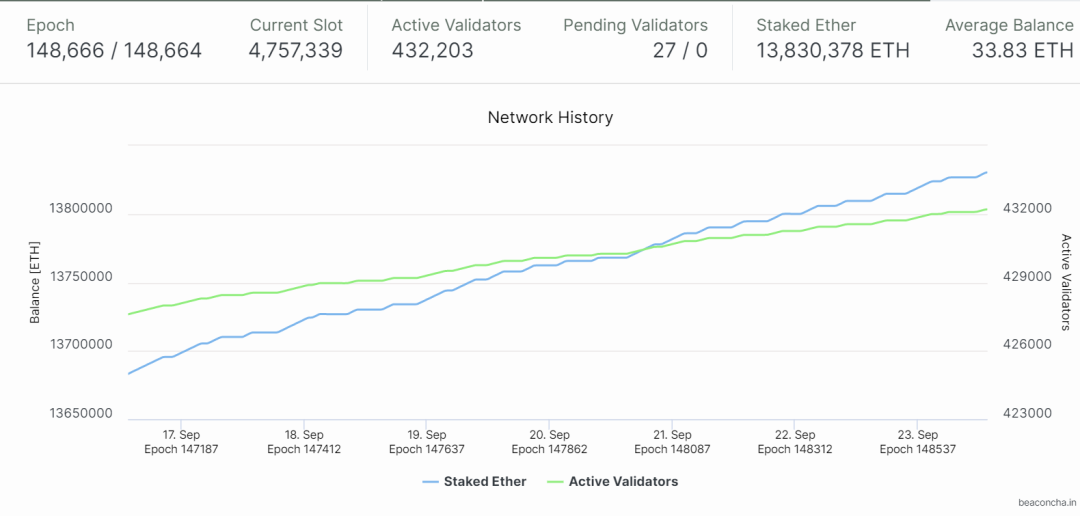

Currently, 13,830,378 ETH are staked on the beacon chain, with 432,203 active validators (as of September 23, 2022). Given PBFT characteristics, the large number of validators on the beacon chain results in high network communication overhead. Simple PBFT is no longer suitable for Ethereum’s network. Therefore, Ethereum improved its network architecture based on PBFT principles, adopting the Gasper algorithm.

Gasper serves as the finality gadget within the beacon chain protocol, determining which blocks participants should consider finalized and immutable. It also resolves forks by identifying the canonical chain. Gasper generalizes the concept from the paper “Casper Friendly Finality Gadget” (Casper FFG).

Figure 7: Staking and Validator Status

2.1 Concepts

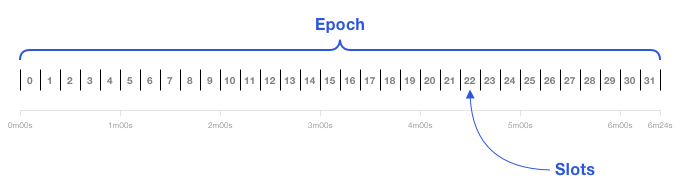

Figure 8: Epoch and Slot Diagram

-

Slot:Post-merge, one block is produced per slot. A committee is responsible for generating the block within a 12-second window.

-

Epoch:Every 32 slots constitute an epoch, lasting 384 seconds (6.4 minutes).

-

Committee:Each committee contains at least 128 validators. Validators perform Attestation on their assigned slot and one validator is randomly selected as the Proposer to produce the block.

-

Attestation:Validators in each slot’s committee must vote and sign the previous epoch, confirming they accept its transactions.

-

Validator:After The Merge, miners are replaced by validators under PoS. Validators stake 32 ETH to participate in block production and signing across epochs.

-

Proposer:Selected from the committee via RANDAO-generated randomness, the Proposer is responsible for packaging the slot’s block.

-

Beacon Chain:A PoS blockchain replacing PoW consensus. Beacon chain nodes support Data Blobs, providing additional storage space for Rollups.

2.2 Process

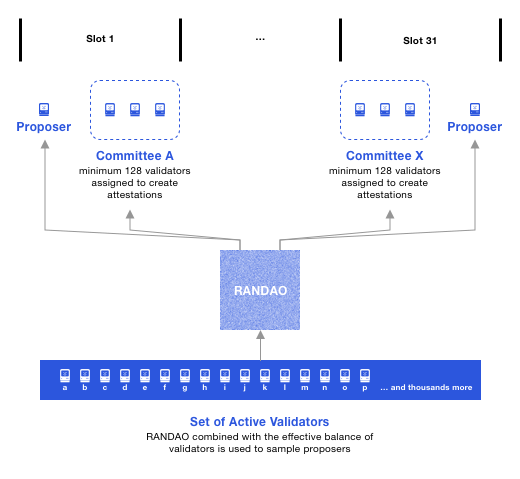

At the start of each epoch, RANDAO assigns a committee to each slot to attest to the previous epoch.

Multiple aggregators are assigned to collect attestations from the committee on the previous epoch and record them into the slot block.

RANDAO uses generated randomness to select the Proposer responsible for block production.

Figure 9: Committee Block Production

During the current epoch, each slot performs attestation on the previous epoch’s checkpoint. Only after two consecutive checkpoints are attested does the prior checkpoint become finalized. Once all 32 slots complete their attestations, the epoch ends. At the beginning of the next epoch’s first slot, the previous epoch achieves finality—requiring two full epochs (because if conflicting checkpoints exist beyond two attested ones, at least 1/3 of validators must have acted maliciously, e.g., block heights 32, 64, 96; if 64 fails but 96 succeeds, then 32 becomes finalized), taking 12.8 minutes total. Transactions are thus confirmed on-chain—this is finality.

2.3 Features

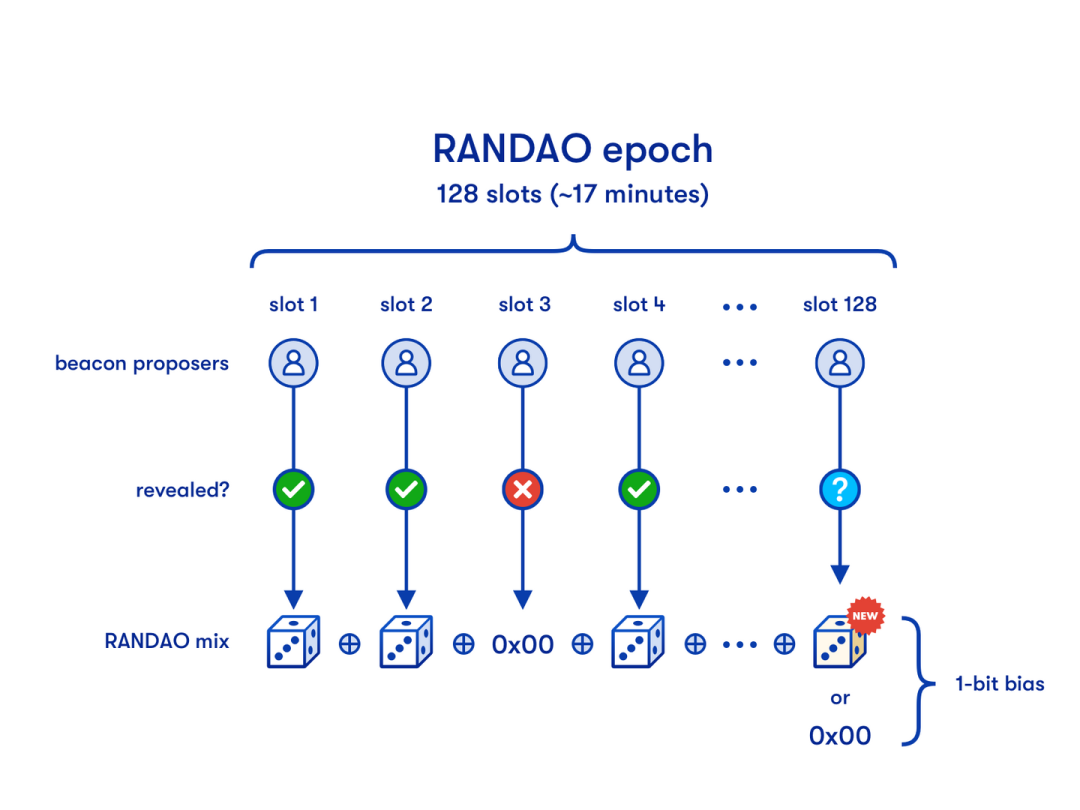

RANDAO provides on-chain randomness. The random number generated by RANDAO is embedded into the Execution Layer Block, enabling smart contracts to directly utilize it. With native on-chain randomness, new DeFi applications may emerge—such as gambling dApps that can trust and use RANDAO’s randomness.

Figure 10: RANDAO

2.4 Latest Message Driven GHOST (LMD-GHOST)

Ethereum’s new PoS consensus uses LMD-GHOST as the fork choice rule. During a fork, GHOST selects the subtree receiving more messages. The idea is to consider only each validator’s latest vote when calculating the chain head, ignoring past votes, thereby reducing computational load.

For further study, refer to: https://eprint.iacr.org/2013/881.pdf

2.5 Emerging Issues

-

Increased Communication and Verification Costs: Are more validators always better? Not necessarily. While increased validator count benefits data availability sampling (DAS) and decentralization, it also increases per-slot validator count, raising communication burden between aggregators and validators. Additionally, aggregated signature verification costs grow, increasing node operational overhead.

-

Long-Range Attacks: A long-range attack occurs when a validator, after withdrawing staked ETH from the beacon chain, uses old private keys to maliciously fork from a previously signed block—since they no longer have stake on-chain—and rapidly generate empty blocks up to current height, attacking the network. Ethereum mitigates this by voting on Pre-Epoch checkpoints, continuously advancing the initial state forward to prevent such attacks.

#3Ethereum Staking

3.1 Staking

Staking Threshold: Validators must deposit 32 ETH as collateral to fulfill their duties and participate in consensus block production.

Validator Responsibilities: Produce blocks and attestations within protocol-specified timeframes.

3.1.1 Staking Methods

-

Solo Staking:Solo stakers run their own validator node on a cloud server after self-funding 32 ETH. Alternatively, they can host servers at home. Cloud hosting offers greater stability, minimizing downtime penalties due to power outages or internet issues. Home setups reduce hardware and networking costs compared to cloud services. Stakers can choose their preferred hosting method.

-

Staking Pools:Since 32 ETH is a substantial sum for average users, staking pools emerged to allow small investors to participate. Lido dominates as a semi-decentralized, permissioned solution. Others like Rocket Pool and Swell offer higher decentralization. Aggregators like Unamano further support and develop the Ethereum staking ecosystem.

In node operations, Lido appoints professional operators to run nodes—a point of centralization. Operators hold signing private keys, so users partially trust Lido and its operators. For withdrawal keys, pre-July 2021, withdrawals went to a 6-of-11 multisig address managed by industry veterans. Post-July 2021, withdrawals go to an upgradeable contract managed by DAO. Rocket Pool takes a more decentralized approach—anyone with 16 ETH and proper hardware can operate a node. Though lowering entry barriers, Rocket Pool uses $RPL staking to deter operator misbehavior.

Staking pools enable ordinary users to deposit small ETH amounts and earn staking rewards, issuing liquid staking tokens like stETH and rETH. This enhances capital efficiency and strengthens Ethereum’s decentralization—a widely supported direction.

-

CEXs and Centralized Custodians:Beyond solo staking and pools, centralized exchanges and asset managers are major Ethereum staking participants. Coinbase and Binance offer staking services, pooling small ETH deposits for low-risk participation. Each method varies in decentralization and security—depending on whom stakers trust—but all capture funds and users, collectively securing Ethereum.

3.1.2 Risks and Concerns

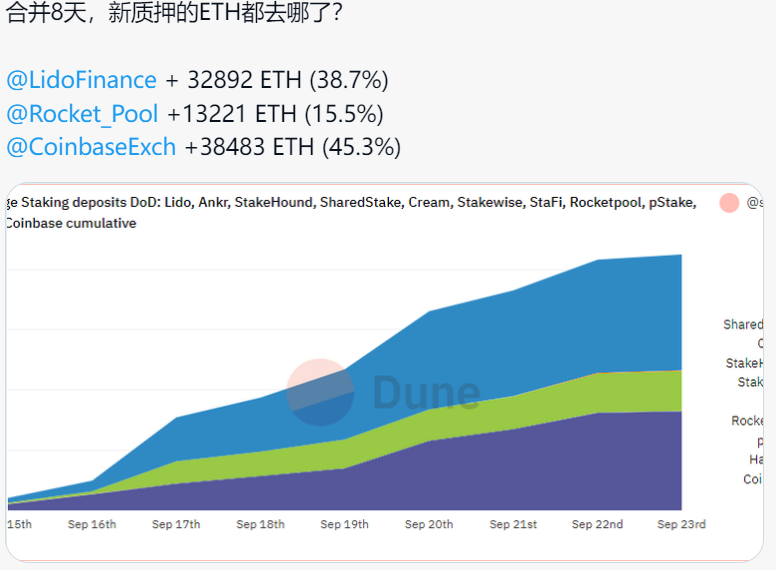

Is everything truly resolved post-merge? Probably not. Consider the following data showing potential outcomes once beacon chain withdrawal restrictions lift.

Figure 11: Post-Merge ETH Staking Distribution

Currently, most staked ETH is concentrated in Lido, Coinbase, and solo staking. Post-merge, new staking flows heavily favor centralized entities like Lido and Coinbase. Once withdrawals are enabled, I believe previously staked ETH will redistribute into these platforms. Over time, Lido and Coinbase could control a growing share of validators and staked ETH, posing serious threats to Ethereum’s decentralization. Once dominant, these pools could reject competing transactions—since they control inclusion—and newly minted ETH would accrue disproportionately to those already holding large stakes. This presents a new challenge to Ethereum’s decentralization—one we hope the community and core developers will address together.

3.1.3 Reward Types

-

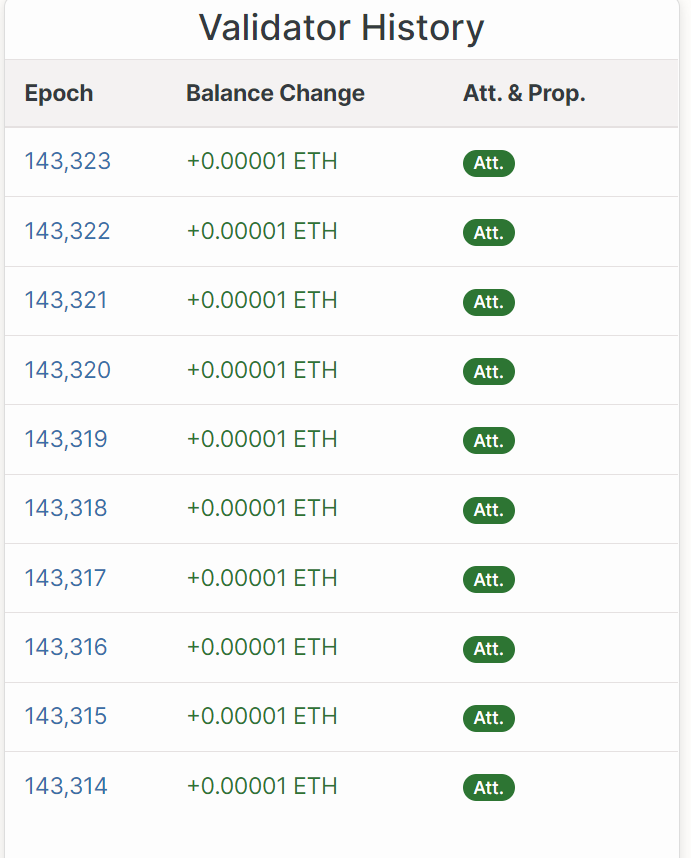

Attestation Rewards:Each slot’s committee must attest to the previous epoch’s checkpoint. Successful attestations yield rewards, forming part of validator income. (High probability, low reward)

Figure 12: Attestation Rewards

-

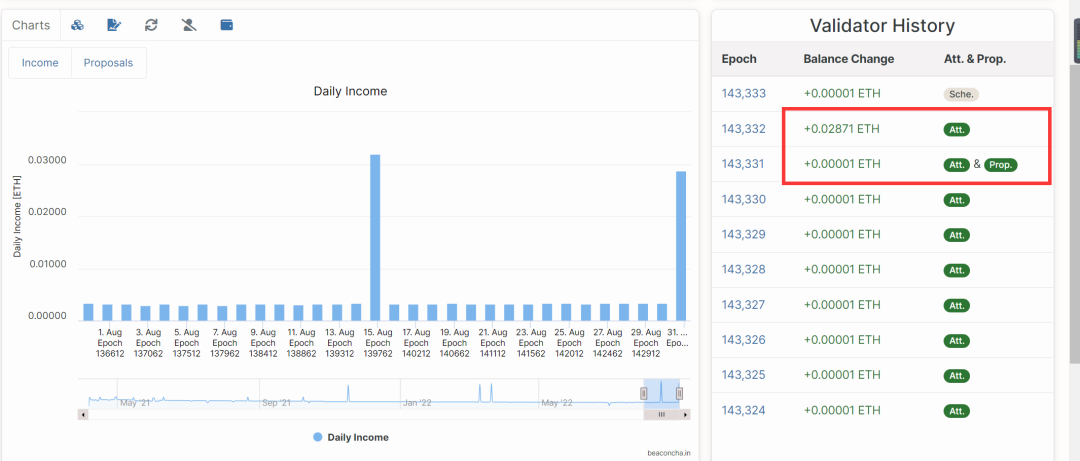

Block Proposal Rewards: One validator per slot is selected as proposer to package the block. Selected proposers receive proposal rewards. (Low probability, high reward)

Figure 13: Proposal Rewards

-

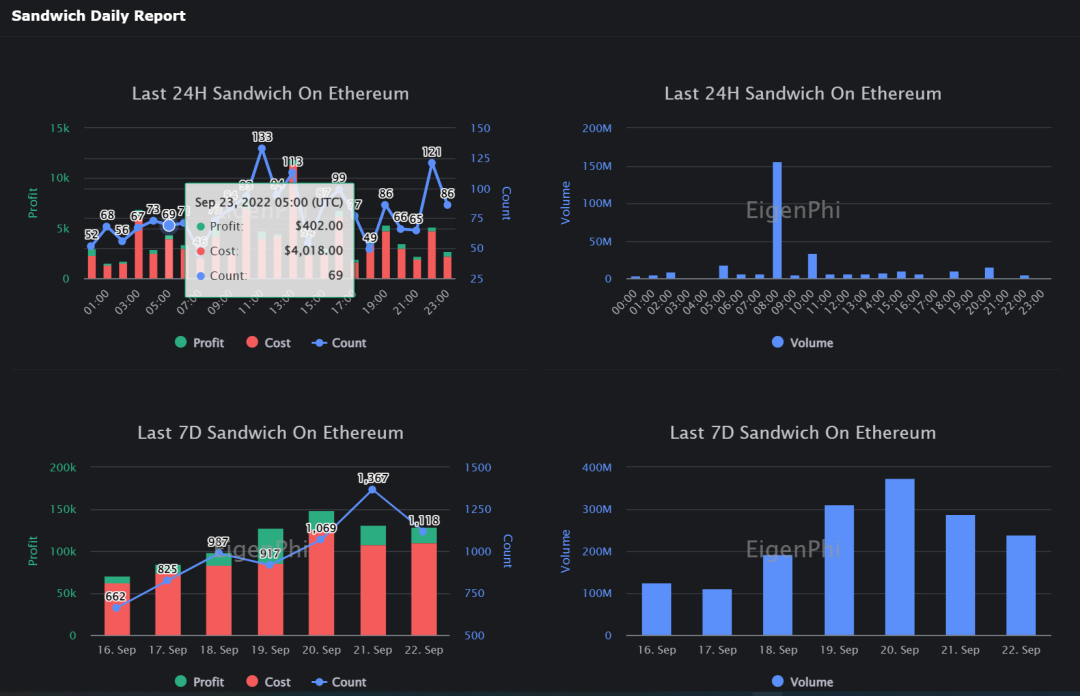

MEV (Maximal Extractable Value) Income:MEV includes gas fee revenue and profits from strategies like sandwich attacks. According to EigenPhi, weekly sandwich attack volumes exceed $100M, peaking near $400M. MEV has become a key component of validator income.

Figure 14: MEV Post-Merge

3.1.4 Penalty Types

-

Downtime Penalties:Failure to produce blocks or attest within expected timeframes.

-

Slashing for Malicious Behavior:Producing two blocks or submitting two attestations within a single slot;Violating Casper FFG rules by proposing invalid blocks.

3.2 Private Key Types

-

Signing Key:Used by validators to sign messages during duty fulfillment, including attesting and proposing blocks. This key is used once every 6.4 minutes (every epoch).

-

Withdrawal Key:Used to withdraw staked assets and block rewards. Must be stored offline. After the Shanghai fork, withdrawal keys enable access to staked ETH and rewards.

3.3 ETH2 Staking Risks

-

Private Key Theft:Compromise of ETH2 signing or withdrawal private keys.

-

Single Point of Failure / Validator Reliability:Currently, validators operate as single machines or nodes. Protocol rules strictly prohibit redundancy—running the same validator on multiple nodes risks slashing. If using staking services, keys reside on cloud servers (e.g., AWS). Any failure halts validation, leading to penalties.

#4Distributed Validator Technology (DVT)

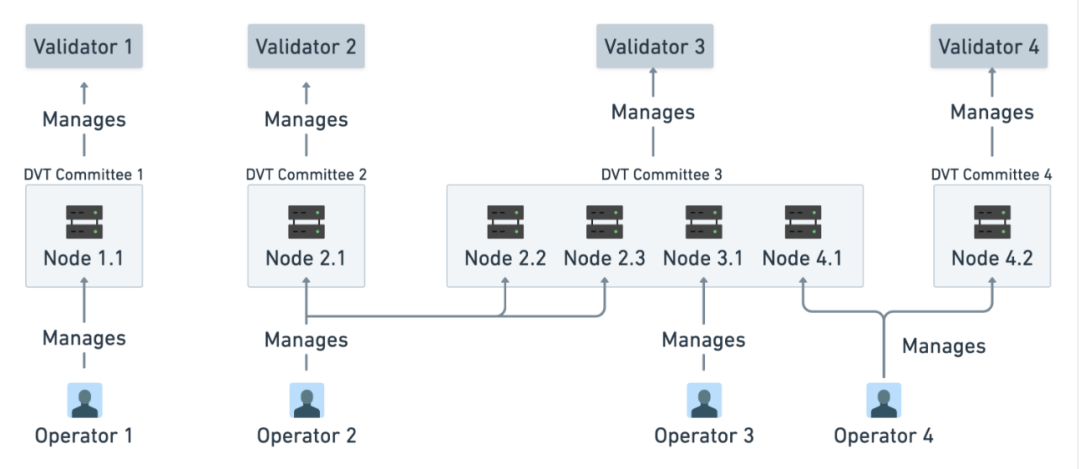

At the staking layer, although decentralized solutions lower entry barriers and improve service decentralization, at the validator level, single points of failure persist. Individual validators run multiple clients; network issues, power outages, or hardware failures cause downtime penalties and failed signature collection. Redundant validator operation isn’t feasible—it creates signature conflicts interpreted as network attacks. However, splitting the signing key via DVT technology reduces single-point failure risks. It also allows node upgrades without causing widespread outages during network upgrades. Let’s explore further!

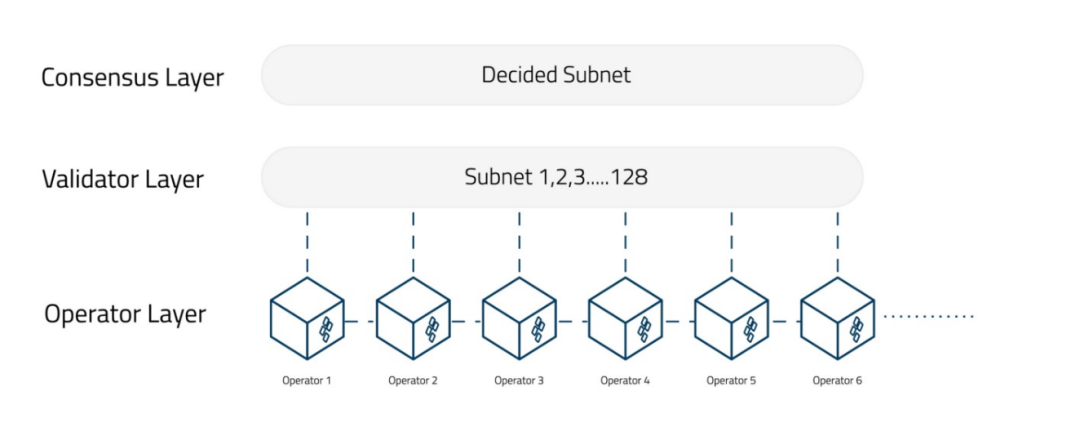

4.1 Concept

-

Operator:An individual or entity running one (or more) nodes.

-

Operator Node:Hardware and software performing Ethereum validator tasks. These tasks can be executed independently or collaboratively using DVT tools.

-

Distributed Validator Technology:A technique distributing a single Ethereum validator’s workload across a group of decentralized nodes. Compared to running a validator client on a single machine, DVT provides enhanced security and decentralization.

Figure 15: Relationship Between Validators, Nodes, Committees, and Operators

4.2 Components Required for Distributed Validator Nodes

-

Ethereum Execution Layer Client

-

Ethereum Consensus Layer Client

-

Ethereum Distributed Validator Client

-

Ethereum Validator Client

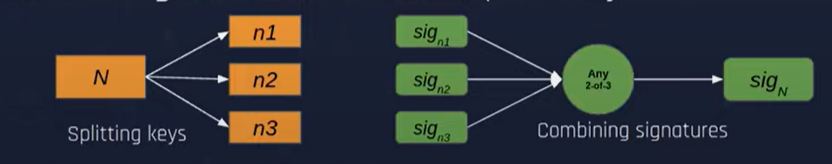

4.3 How DVT Mitigates ETH2 Staking Risks

-

Private Key Theft

-

Threshold signature schemes (m-of-n) prevent private key theft

-

A full validator key is split into multiple partial keys

-

Partial keys are aggregated to produce a complete signature

Figure 16: Key Splitting and Aggregate Signatures

-

Node Downtime

-

Crash Faults:

Cause: Crashes due to power loss, network disconnection, hardware failure, or software bugs;

Mitigation: Redundant backup deployment across multiple locations prevents node disconnection;

-

Byzantine Faults:

Cause: Caused by software bugs or network attacks;

Mitigation: Multiple participating nodes reach consensus—no single node can act unilaterally.

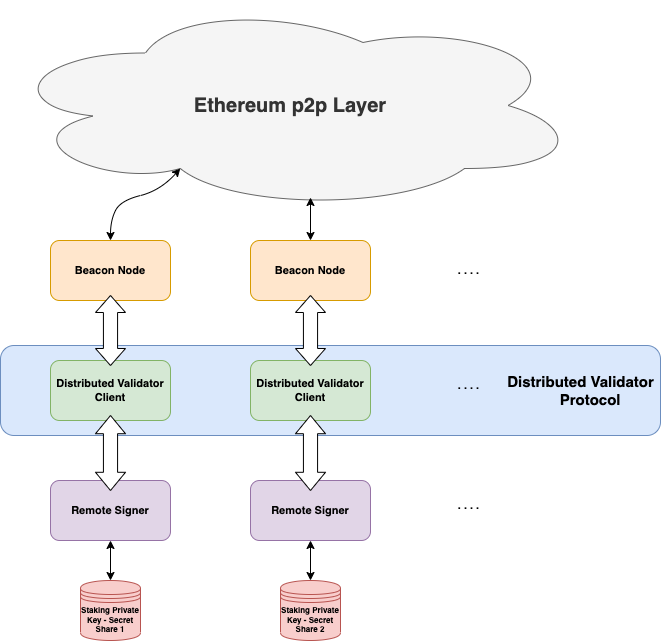

4.4 Overall Architecture

Figure 17: DVT Overall Architecture

-

Distributed validators remotely sign messages using secret-shared private keys

-

Within the distributed validator client, aggregate signatures combine individual validator signatures. Once threshold is met, the block is signed.

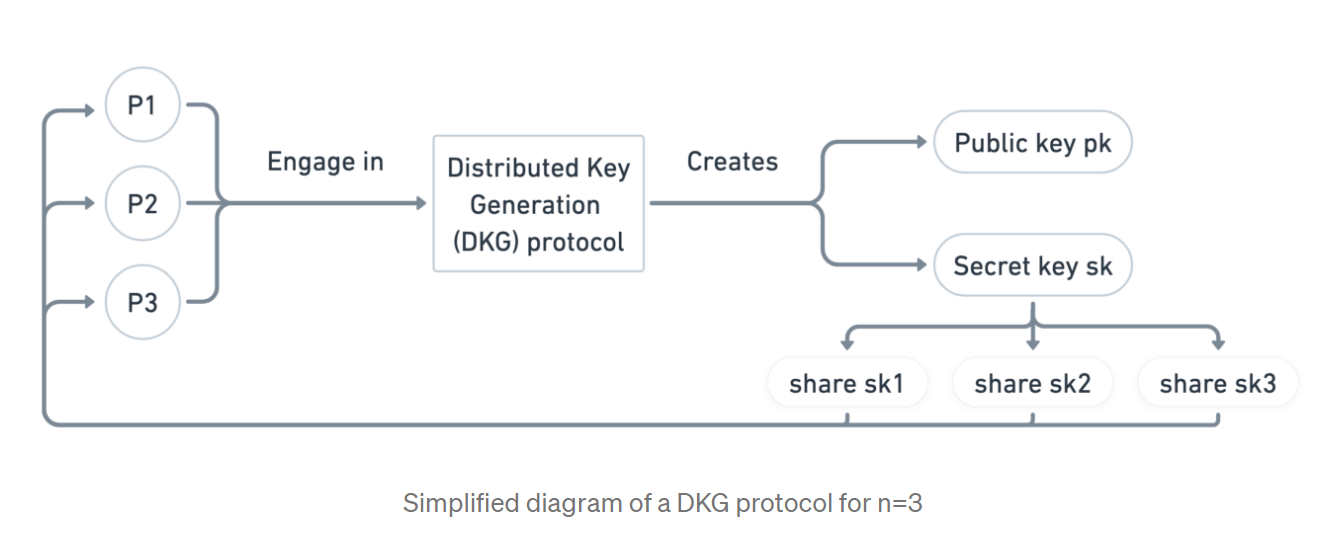

4.5 Two Approaches to Implementing DVT

-

DVT Using SSS:An entity staking 32 ETH creates a signing key pair (sk, pk) and withdrawal key, then runs a Secret Sharing Scheme program to securely distribute shares of sk among committee nodes.

-

DVT Using a DKG Protocol:In the DKG approach, no single entity distributes key shares. Instead, a group of validator committee nodes jointly run the DKG protocol. A secret-public key pair (sk, pk) and n shares sk_1,...,sk_n are created, with the i-th node holding share sk_i (i=1,...,n).

Figure 18: DKG Protocol

4.6 Threshold Signature Schemes (TSS)

When validators agree on a block requiring a signature, BLS threshold signatures are used. This scheme allows N validators to jointly sign data, producing a complete signature if t+1 (0

#5DVT Through Leading Projects

5.1 SSV

On the surface, SSV offers a robust, decentralized pathway into Ethereum staking. Digging deeper, SSV functions as a complex multi-signature wallet with a consensus layer, acting as a buffer between beacon chain nodes and validator clients.

5.1.1 Key Configuration Components

-

Distributed Key Generation:Operators run the SSV program to compute a shared public-private key set. Each operator holds only a portion of the private key, ensuring no single operator can unilaterally control or influence decisions.

-

Shamir Secret Sharing:This mechanism reconstructs the validator key using a predefined threshold of KeyShares. Individual KeyShares cannot sign messages alone. SSV leverages BLS technology to aggregate signatures, creating a complete validator key signature. Combining Shamir and BLS, the validator’s private key is sliced, shared, and re-aggregated when signing is required.

-

Multi-Party Computation:Applying secure multi-party computation (MPC) to secret sharing enables SSV’s KeyShares to be securely distributed among operators and allows decentralized computation of validator duties without reconstructing the full validator key on any single device.

-

Istanbul Byzantine Fault Tolerance Consensus:Binding it all together is SSV’s consensus layer, based on the Istanbul Byzantine Fault Tolerance (IBFT) algorithm. This algorithm randomly selects a validator node (KeyShare) to propose blocks and share information with other participants. Once the predetermined KeyShare threshold validates the block, it is added to the chain. Thus, consensus can be reached even if some operators (up to the threshold) are faulty or offline.

Figure 19: SSV V2 Network Topology

5.1.2 Three Participant Types in the SSV Ecosystem

-

Stakers: Exchanges, service providers, or individual ETH holders utilizing SSV/DVT technology to maximize validator effectiveness, security, and decentralization. Stakers pay operators in SSV tokens for validator management.

-

Operators: Operators provide hardware infrastructure, run the SSV protocol, and maintain overall health of validators and the ssv.network. Operators set service fees in SSV tokens and charge validators for operational and maintenance costs.

-

DAO (SSV Token Holders): The ssv.network DAO decentralizes ownership and governance of the ssv.network protocol and treasury. SSV is the network’s native token. Anyone holding SSV tokens can participate in the DAO, voting on proposals and other matters requiring approval. The amount of SSV held determines voting power on network-affecting decisions.

5.1.3 Responsibilities of the ssv.network DAO:

-

Operator Scoring:ssv.network relies on operators and applies a 0–100% decentralized, transparent scoring system for their quality, experience, and services. The DAO also reviews "Verified Operators" (VOs) and maintains the VO list. Stakers can view and use these rankings to select operators managing their validators.

-

Network Fees:To use ssv.network, stakers pay network fees. A fixed fee per validator is added to operator fees. Network fees flow directly into the DAO treasury, funding further development of the SSV ecosystem and activities approved via DAO voting.

-

Treasury:Network fees paid by stakers fund the DAO treasury, supporting projects developing the

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News