How Gyroscope solves the dilemma of decentralized stablecoins?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

How Gyroscope solves the dilemma of decentralized stablecoins?

Decentralized stablecoins are one of the best use cases for cryptocurrency.

Author: RainandCoffee

Translation: TechFlow

Preface

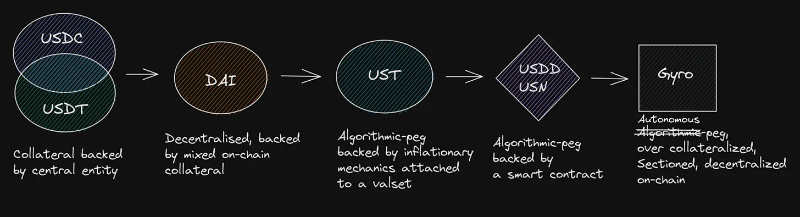

Recent months have shown that algorithmic stablecoins with varying degrees of collateral support are not scalable. Against this backdrop, we discovered Gyroscope—a fully collateralized and decentralized dynamic stablecoin protocol. We believe they are building an exceptionally resilient system capable of sustaining a decentralized stablecoin through diverse market conditions. Moreover, we believe decentralized stablecoins represent one of crypto’s strongest use cases.

History of Stablecoins

To understand how Gyroscope aims to revolutionize the current stablecoin paradigm, we must first explore how stablecoins have evolved over time and examine their key differences.

Let us begin with the history of stablecoins, then proceed to review existing types and some notorious death spirals.

What Is a Stablecoin?

A stablecoin is a cryptocurrency designed to maintain a stable value relative to an external asset—typically the US dollar—by minimizing price volatility through full collateralization or other mechanisms.

The primary purpose of stablecoins is to neutralize the speculative nature of cryptocurrencies and establish USD/token markets on DEXs.

The history of on-chain stablecoins began in June 2014 during a hot summer, when the first on-chain stablecoin was launched on the BitShares blockchain—bitUSD.

If you're a crypto veteran, you might remember some figures behind BitShares, such as Daniel Larimer of EOS.

How Did BitUSD Work?

Its mechanism was actually similar to some "algorithmic" stablecoins seen in recent years. Let me explain.

Users could mint and redeem BitUSD; however, the exchange rate was determined by the BitUSD/BitShares pair on a decentralized exchange, unrelated to the US dollar.

Thus, its price referenced itself and attempted to maintain its peg via arbitrage, much like what led to UST's collapse.

In this case, if the value of the collateral (here, BitShares) dropped, any BitUSD holder could redeem $1 worth of BitShares.

However, this assumed that BitUSD's market price remained at $1 and sufficient BitShares existed as collateral.

So, it wasn't exactly like LUNA/UST (where UST could always be redeemed for $1 worth of LUNA).

Nevertheless, the same fundamental issues that plagued UST had already existed—even as early as 2014.

USDT

USDT (Tether), one of the earliest stablecoins still maintaining its peg today, entered the market in 2015 via Bitfinex.

USDT is an on-chain stablecoin backed by off-chain collateral—real-world assets—and remains the most popular stablecoin in existence (with a market cap of approximately $67.5 billion).

Since its inception, Tether has weathered numerous events and controversies.

Yet despite these challenges, it has managed to retain its position, now standing alongside stablecoins like USDC.

While Tether excels at solving liquidity problems, it reintroduces a core issue that blockchains aim to solve: centralization.

DAI was created specifically to address this centralization problem (although it remains relatively centralized).

However, DAI brings its own unique challenges—during contractionary (and sometimes expansionary) market events (i.e., market volatility), when the collateral backing DAI (primarily ETH) gets liquidated, DAI may lose its dollar peg.

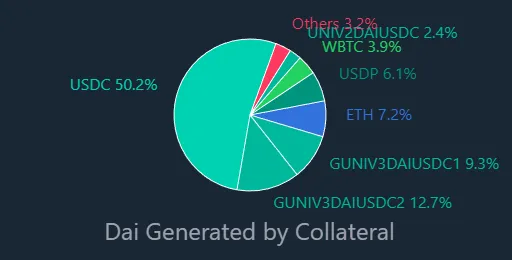

Currently, DAI is backed by about 75% USDC, along with some volatile assets (like ETH), making it essentially a decentralized derivative of USDC itself.

TerraUSD’s algorithmically-pegged stablecoin represented an algorithmic and fundamentally uncollateralized model, allowing real-time dynamic adjustments to market forces—similar to what was used in BitShares—but ultimately collapsed after several modifications.

Therefore, let’s summarize the existing types of stablecoins and map them out to better understand their differences.

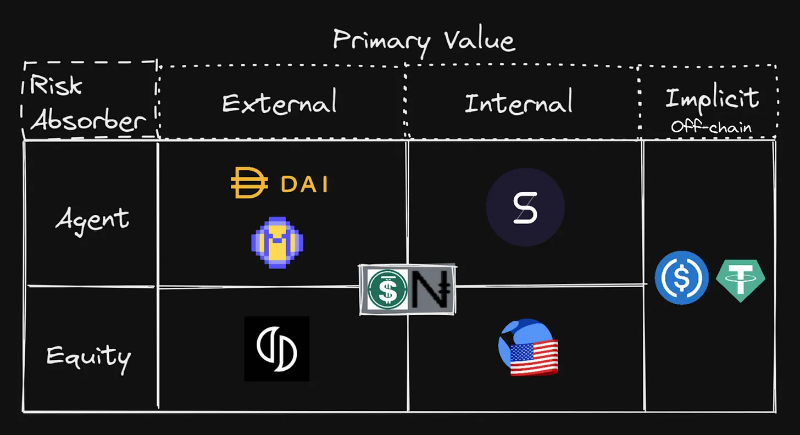

1. Off-Chain Collateralized

This category includes two of the most popular stablecoins—USDC and USDT—with a combined market cap of approximately $119 billion.

They are backed by real-world collateral held by centralized entities and, in some cases, verified by external auditors.

Keep in mind that these types of stablecoins are typically backed by fiat, commodities, and other financial instruments.

2. On-Chain Collateralized (+ Stablecoins Backed by Yield-Generating Assets)

These stablecoins are backed by other on-chain cryptocurrencies and, in some cases, partially by off-chain collateral (e.g., DAI).

The peg is enforced on-chain via smart contracts and maintained by arbitrageurs, while observers/liquidators clear positions when collateral thresholds are breached.

Some on-chain pegs are also supported by yield-generating assets, such as MIM and YUSD.

3. Uncollateralized/Algorithmic

These stablecoins use algorithms to control money supply, often by issuing assets held by the stablecoin entity.

You can think of this type as akin to a central bank printing and burning currency—but on-chain.

In most cases, there is no collateral (unless funds are raised to support the peg, like Luna or Tron’s reserves). The peg is protected on-chain through arbitrage-driven minting/burning mechanisms. In Luna’s case, internal assets were the primary shock absorbers, leading to hyperinflation during the death spiral.

To better understand how various stablecoins absorb risk and derive value, let’s visualize them in a table.

This clearly shows that the current market is dominated by stablecoins like USDT and USDC, both backed by centralized entities.

The only somewhat decentralized stablecoin close in scale is DAI, though it lags significantly behind, with a market cap of around $6.4 billion.

MakerDAO recently discussed shifting from USDC to more decentralized assets like ETH—an undoubtedly exciting development.

UST was the only decentralized stable asset approaching the market caps of the two major centralized players. However, this proved unsustainable.

Over the years, many failed stablecoins suffered from panic among investors—triggered by various market events—leading to “death spirals” where the stablecoin lost its peg and, consequently, trust.

Another good example is Basis Cash, which peaked at a market cap of just $30 million. As mentioned earlier, Basis Cash employed a seigniorage-style algorithm involving a stablecoin and a separate token to maintain the peg via minting and burning through arbitrage.

Other examples include attempts to enforce partially crypto-collateralized schemes, such as what occurred in UST’s final months. However, when the peg-enforcing token becomes overvalued and unable to absorb the growing market cap of the stablecoin, it inevitably leads to a death spiral—as seen with Luna and Iron.

Another critical factor in maintaining a stablecoin’s peg is trust, as exemplified by Tron’s USDD. Technically, USDD is overcollateralized by BTC and USDC/T reserves. At the time of writing, USDD trades at $0.98 (July), reflecting market distrust in the system and limited public participation in arbitrage opportunities.

Now that we’ve covered the history of stablecoins—including both successes and failures—let’s turn to events that can positively impact stablecoin prices, such as asset appreciation, before moving on to Gyroscope.

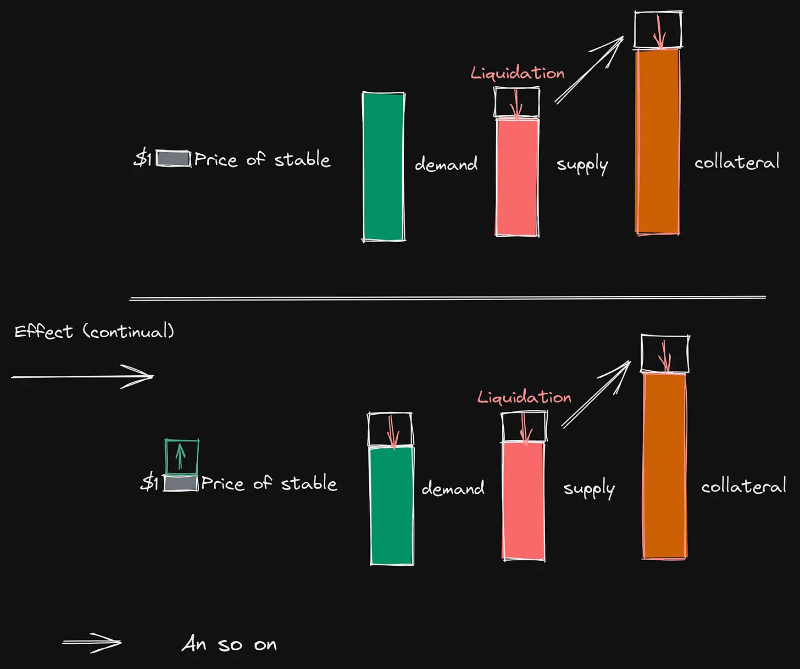

Deleveraging spirals are one way stablecoin prices can rise rather than remain pegged purely through arbitrage. During collateral shocks, faster collateral withdrawals may occur.

When speculative liquidations begin—for example, in DAI—they are either automatically executed by the protocol or involve voluntary deleveraging, using collateral to buy back the stablecoin and reduce supply.

In elastic markets, this can have adverse effects, causing supply-demand imbalances.

To counter reduced demand, the stablecoin price must increase to suppress demand further—amplifying the problem.

Under continuous liquidation, rising stablecoin prices require more collateral to reduce supply by the same amount as before.

Once shocks reach collateral value or expected volatility levels, higher anticipated liquidation costs make speculators more likely to increase collateralization.

Hence, DAI maintains very high collateral ratios, typically between 2.5x and 5x, even though the actual required ratio is 1.5x.

Gyroscope

Having reviewed the history of stablecoins, the current market landscape, and how deleveraging spirals occur, let’s now dive deeper into how Gyroscope aims to change this status quo.

At its core, Gyroscope is a protocol enabling the minting of a meta-stablecoin. A meta-stablecoin is composed of a basket of other assets—such as other stablecoins, yield-generating instruments, or volatile assets—which can then generate additional returns.

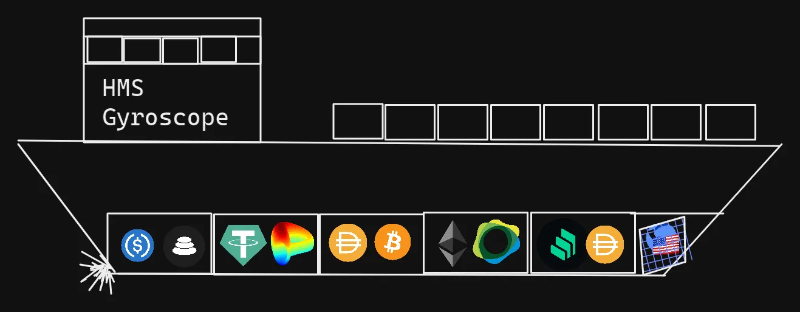

What makes Gyroscope unique is that it is both collateralized and features a distinctive defense mechanism to restore its peg when reserve asset prices decline. This is achieved through a method similar to how ships operate: if a ship springs a leak, flooding is contained within one section, preventing the entire vessel from sinking. Similarly, Gyroscope’s tiered reserves function in the same way—let’s try to illustrate this visually.

Gyroscope is a fully backed stablecoin, aiming for a long-term reserve ratio of 100%. Beyond this, it offers several unique features: all-weather reserves and autonomous price constraints to ensure maximum price stability.

What are all-weather reserves? All-weather reserves refer to the basket of assets backing Gyro. Initially, these will mostly consist of other stablecoins, but over time, the reserve will diversify to include other tokens. This diversification spreads risk across all potential scenarios. Autonomous price constraints mean that the minting and redemption prices of the stablecoin are set algorithmically to balance the goal of tight dollar pegging—especially crucial during crises.

Arbitrage Loop

Like most stablecoins, Gyroscope operates with what we call an arbitrage loop. Unlike most centralized stablecoins, however, this process is permissionless because the stablecoin can be minted using $1 worth of assets.

For instance, when the price rises above the peg, more stablecoins can be minted and sold on the market for profit. These profits can also be used to grow Gyro’s underlying reserves.

When the stablecoin price drops below the peg, units can be bought on the market and redeemed for $1 worth of reserve assets.

The combination of the arbitrage loop and all-weather reserves forms the first line of defense in maintaining Gyro’s peg. This must happen permissionlessly; otherwise, the peg cannot be reliably arbitraged—just look at USDD!

Additionally, the peg cannot be restored solely using endogenous assets—it must also have exogenous asset support. Hence, Gyroscope employs all-weather reserves.

If larger events occur and the reserves are impacted, additional defense layers kick in to maintain the peg and ensure stability.

Tiered Reserves

As previously mentioned, multiple defense layers exist to maintain the stablecoin’s peg—the first being the one described above.

The second layer—tiered reserves—stores all issuance profits and diversifies DeFi risks.

This reserve aims to maintain full collateralization at all times.

Initially, it will consist mainly of stablecoins, but as illustrated with the ship analogy, it will eventually hold other assets as well.

These assets will start fully backed, but if the underlying asset values decline, they may become undercollateralized.

However, when leveraged loans exist within the system, they are overcollateralized.

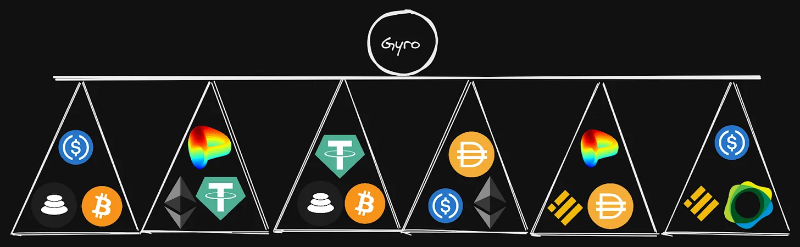

These vaults are designed to provide controlled risk exposure, with minimal overlap between them.

This means if one vault fails, it won’t affect the others.

Even if one vault fails, the system will continue enforcing autonomous price constraints using unaffected reserves to maintain stability.

These reserves also help earn yield on assets, ultimately helping restore the reserve to its original strength.

The reason for this design is to isolate risks as much as possible so that if one component fails, it doesn’t infect the rest.

This means Gyroscope’s reserves are split into vaults (triangles) that help contain risk.

Thus, if one vault fails, it won’t compromise the others.

If a vault collapses, the dynamically priced constraint backed by the remaining reserves activates to help maintain the peg.

Further Measures

The third line of defense, which I just mentioned, is dynamic pricing. When stablecoin units become undercollateralized, the redemption curve begins reducing redemption quotes—acting as a circuit breaker to preserve stability. This mechanism is unlikely to be used frequently, except during extreme market events.

Reducing redemption quotes deters bank runs and attacks on the peg. It also rewards users who wait for market recovery.

Importantly, while holders can still exit their stable positions, there’s now greater incentive to “bet” on the peg returning to its target. Over time, as redemption prices autonomously return to the peg, outflows will halt—or reserves will recover via yield generation.

Other stabilization mechanisms also exist to support the peg.

One resembles Maker’s Peg Stability Module.

However, it has distinct features. While Gyroscope allows exchanging $1 worth of assets for its stablecoin, it also enables diversification of the reserve supporting the stablecoin.

Moreover, in the long run, it won’t primarily rely on custodied stablecoins (unlike DAI, which is ~70% backed by USDC).

It also offers flexibility to survive decoupling events, even amid reserve fluctuations.

This is enabled via leveraged loan mechanisms when reserves are undercollateralized. If the stablecoin price falls significantly below the peg (e.g., during a market crash), leveraged loan holders can deleverage their positions at a discount.

This reduces stable asset supply and helps push the price back toward $1 (similar to how MIM operates).

Last Resort

Gyroscope’s last resort is only used when all else fails. This mechanism involves recapitalizing reserves through auctions of governance tokens or commitments to future protocol-derived revenues from reserves or transaction fees.

This works similarly to Maker’s support mechanism and would only occur as an absolute last resort.

Oracle Feeds

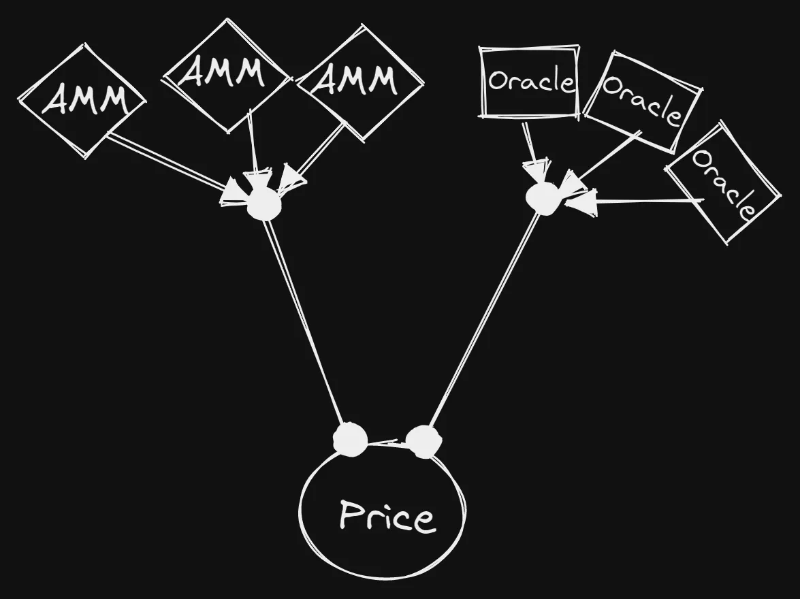

Gyro’s oracle mechanism differs significantly from other protocols. It relies on multiple on-chain consistency checks, circuit breakers, and anti-manipulation methods to price LP and vault equity.

Accurate price feeds are particularly important when stablecoins are used in DeFi.

A prime example is the UST collapse, during which several protocols were exploited due to incorrect UST price data from their oracles.

This allowed attackers to borrow large sums based on inaccurate pricing. The recent Inverse Finance vulnerability followed a similar pattern, exploiting oracle flaws.

Tiered price feeds involve obtaining on-chain references from AMMs, then cross-referencing those prices with multiple oracles.

By layering prices from different sources, discrepancies and anomalies can be easily detected on-chain.

This also means price manipulation would require massive capital across multiple platforms.

If discrepancies are detected, the system can pause trading until the issue is resolved. Most projects rely on a single oracle, making them easier to exploit.

Dynamic Pricing and More

Before discussing Gyroscope’s unique governance mechanism, let’s delve deeper into its dynamic pricing module and the functionalities it enables for the protocol.

Gyroscope utilizes two distinct automated market-making mechanisms:

- The first is the Dynamic Stability Mechanism (DSM), which quotes minting and redemption prices for the stablecoin while supporting shock absorption for the reserve assets.

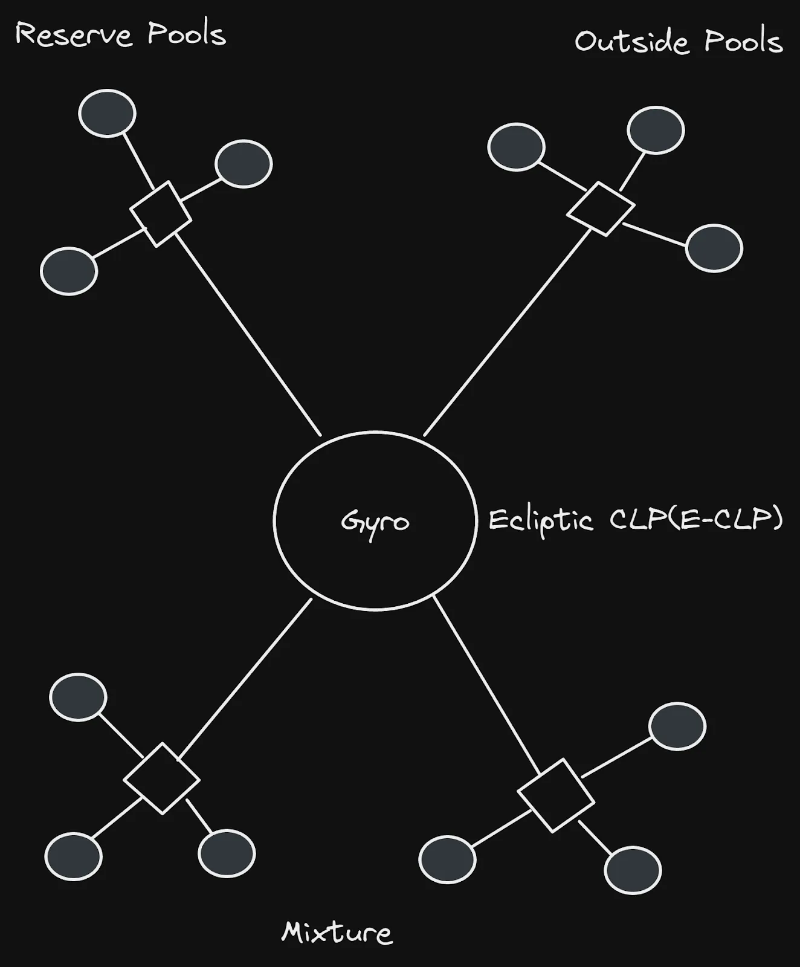

- The second pricing module is the Concentrated Liquidity Pool (CLP), which uses customized Balancer v2 pools to concentrate liquidity within specific price ranges. This is made possible through collaboration with Balancer, enabling the necessary logic for custom AMMs.

The CLP concentrates liquidity based on information provided by the DSM regarding the stablecoin pairs backed by Gyroscope’s reserve assets.

The CLP functions similarly to Uniswap v3 but on Balancer, specifically optimized for the highest-volume trading ranges.

This ensures that Gyro’s stablecoin will have efficient entry and exit paths.

Furthermore, the CLP is isolated, meaning—like the tiered reserves—any failure won’t impact the rest of the system.

These pricing modules enable some remarkably unique designs beyond Gyroscope’s core protocol mechanics.

It allows building a DEX capable of withstanding asset failures—such as what Osmosis effectively utilized during the UST collapse.

This design allows secondary markets to act as AMMs, reserve pools, etc., operating as efficiently as possible. From an overview perspective, the various pools would look like this:

Once Gyroscope accumulates a robust reserve as its stablecoin gains widespread adoption, it can remain stable at $1 under any market condition.

During extreme events, the peg might shift temporarily, but the system is designed to make such occurrences highly improbable. Even during short-term decoupling, tiered reserves and yield mechanisms will help restore the stablecoin to its peg.

Governance

Gyroscope also innovates in governance by implementing a new system called Optimistic Approval.

Optimistic Approval aims to align protocol governors with the long-term interests of the protocol itself.

Thus, Gyroscope’s governance focuses not on short-term, quick ideas, but on maximizing the protocol’s long-term health.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News