Câu chuyện cũ ở Boston: Trung tâm công nghệ từng một thời của nước Mỹ đã suy tàn như thế nào?

Tuyển chọn TechFlowTuyển chọn TechFlow

Câu chuyện cũ ở Boston: Trung tâm công nghệ từng một thời của nước Mỹ đã suy tàn như thế nào?

Câu chuyện Boston cho thấy điều gì xảy ra khi các vòng phản hồi tiêu cực về văn hóa và quản lý tác động qua lại lẫn nhau.

Tác giả: Will Manidis

Biên dịch: TechFlow

Năm 2004, nếu bạn hỏi một nhà đầu tư công nghệ rằng đâu là nơi có những công ty phần mềm tốt nhất thế giới, họ sẽ đưa ra hai câu trả lời: Boston và San Francisco.

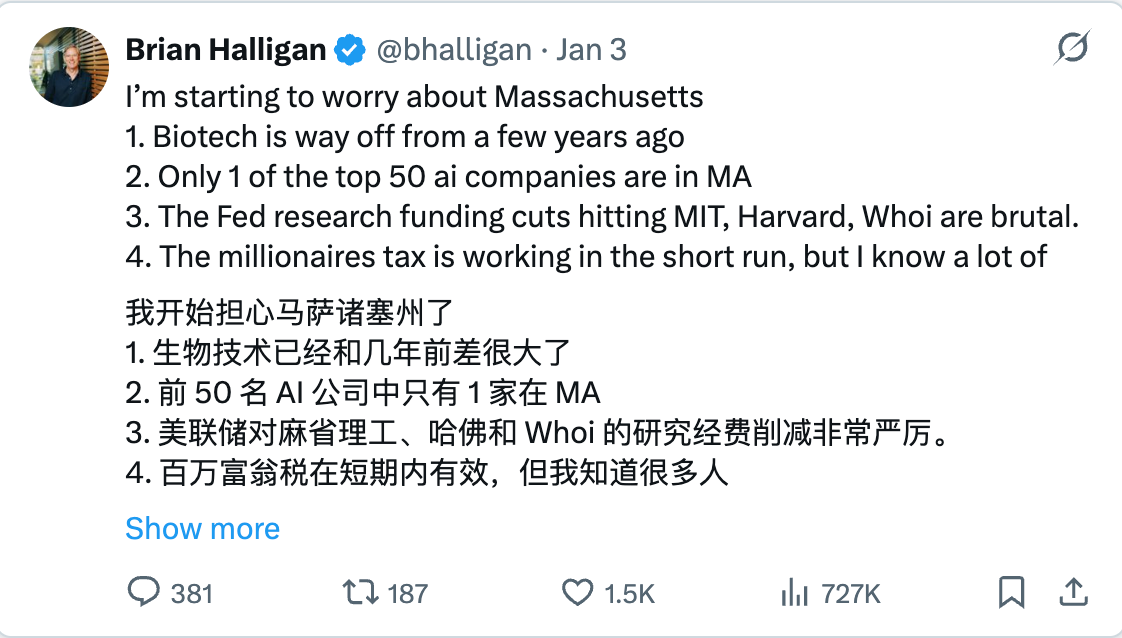

Rõ ràng, ngày nay tình hình đã hoàn toàn khác. Trong hai thập kỷ qua, San Francisco đã tạo ra giá trị doanh nghiệp lên tới 14 nghìn tỷ USD, trong khi Boston chỉ đóng góp 100 tỷ USD.

Nếu lúc đó bạn nói với nhà đầu tư ấy rằng New York – thành phố từng nổi tiếng với “vinh quang tài chính của cocaine và vest kẻ sọc xám” – sẽ thay thế Boston trở thành trung tâm công nghệ khu vực, chắc chắn họ sẽ cho rằng bạn điên rồi.

Vậy tại sao Boston lại đánh mất vị thế của mình? Đây là một câu hỏi đáng được nghiên cứu kỹ lưỡng.

Xét về các yếu tố đầu vào, thành phố này dường như có mọi điều kiện thuận lợi. Hai trường đại học hàng đầu thế giới tọa lạc tại đây (Đại học Harvard và Viện Công nghệ Massachusetts - MIT). Hatchery khởi nghiệp nổi tiếng Y Combinator cũng được thành lập ở đây. Không thể phủ nhận rằng đây là một trong những thành phố đẹp nhất nước Mỹ. Mark Zuckerberg (Mark Zuckerberg) từng học đại học tại đây. Các nhà sáng lập Stripe, các nhà sáng lập Cursor và Dropbox cũng từng theo học ở đây. Vậy vấn đề nằm ở đâu?

Để hiểu quy mô sự suy thoái của Boston, ta cần nhớ rằng trong nhiều thập kỷ, "đường cao tốc 128" (Route 128) của Boston từng là trung tâm của thế giới phần mềm. Công ty thiết bị số (DEC) từng là công ty máy tính lớn thứ hai toàn cầu, đỉnh cao có đến 140.000 nhân viên. Công ty Lotus phát triển ứng dụng then chốt giúp doanh nghiệp bước vào thời đại PC. Akamai xây dựng nền tảng cơ sở hạ tầng cho internet hiện đại. Vậy Boston đã sai ở điểm nào?

Đây là một câu hỏi đáng để bàn luận. Tuy nhiên, bất kỳ ai cố gắng trả lời thường đưa ra một trong hai câu trả lời:

- "Sự suy tàn của Boston bắt đầu từ việc Zuckerberg không thể huy động vốn ở đây, buộc phải chuyển sang bờ Tây."

- "Ai bảo Boston không còn hành động? Chúng tôi vừa dẫn đầu vòng gọi vốn Series F của TurboLogs với định giá 15 triệu USD."

Tất nhiên, cả hai lập luận trên đều chưa đủ để làm rõ câu chuyện. Việc tìm ra vấn đề thực sự của Boston không chỉ liên quan đến sự sống còn của chính Boston, mà còn là vấn đề then chốt đối với toàn bộ hệ sinh thái công nghệ Mỹ.

Câu trả lời của tôi rất đơn giản: Câu chuyện Boston cho thấy điều gì xảy ra khi các vòng phản hồi tiêu cực về văn hóa và quản lý tương tác lẫn nhau. Với tư cách là một hệ sinh thái công nghệ, sự suy giảm của thành phố này bắt nguồn từ ba lực lượng đơn giản:

1. Một hệ thống quản lý coi doanh nghiệp là phương tiện để chủ sở hữu bất động sản khai thác tiến bộ

Trong nhiều thập kỷ, bang Massachusetts từ chối tuân thủ Quy tắc Miễn trừ Cổ phiếu Doanh nghiệp Nhỏ Đủ Điều Kiện (QSBS) của liên bang. Bang này cuối cùng mới bắt đầu tuân thủ quy định này vào năm 2022. Tuy nhiên, cùng năm đó, họ lại thông qua "thuế triệu phú". Tại Massachusetts, một người sáng lập bán công ty với giá 10 triệu USD sẽ phải nộp 860.000 USD tiền thuế; trong khi người sáng lập tại Austin thì không phải trả đồng nào. Ngoài ra, Massachusetts đánh thuế bán hàng 6,25% lên doanh thu SaaS (phần mềm như dịch vụ), trong khi hầu hết các bang khác hoàn toàn miễn thuế phần mềm.

2. Văn hóa thanh giáo mắc kẹt sâu trong các tổ chức tinh hoa, thiếu khả năng tự giám sát

Sau năm 2010, hoạt động đầu tư mạo hiểm tại Boston chủ yếu không còn nhằm hỗ trợ phát triển doanh nghiệp, mà trở thành hành vi bóc lột các nhà sáng lập, thậm chí giống như vận hành một băng nhóm tội phạm có tổ chức. Những nền tảng văn hóa lẽ ra phải giám sát hành vi này – gồm các nhà tài trợ quỹ, các nhà đầu tư hạn chế (LPs) lớn, và các nhân vật nổi tiếng tham dự các buổi tiệc từ thiện – lại quá gắn bó với các bên gây hại và mạng lưới của họ, đến mức không ai dám lên tiếng. Hiện tượng này khiến môi trường kinh doanh tại Boston luôn chịu một loại "thuế tin cậy" vô hình.

3. Coi tiến bộ công nghệ theo góc nhìn ưu tiên "đầu vào"

Chúng ta có những trường đại học tốt nhất thế giới, chúng ta xây dựng rất nhiều không gian phòng thí nghiệm (dù hiện nay 40% đang bỏ trống), chúng ta tập trung nhân tài xuất sắc nhất hành tinh. Vậy tại sao tất cả điều này lại không hiệu quả? Phải chăng chúng ta không thể tái tạo một trung tâm đổi mới? Liệu vùng đất của chúng ta đã mất đi phép màu?

Nếu ba giải thích trên nghe có vẻ quá đơn giản, thậm chí quen thuộc, thì đúng vậy – bởi vì đây chính xác là vấn đề chung mà toàn ngành công nghệ Mỹ đang đối mặt, và tôi nghi ngờ rằng nó có thể mang đến hậu quả chết người tương tự.

Hệ sinh thái công nghệ về bản chất là những mạng lưới mong manh, tạo ra hàng ngàn tỷ USD lợi ích thuế cho khu vực, nhưng các vật chủ ký sinh (chính quyền) lại không thể cưỡng lại cám dỗ giết con "vịt đẻ trứng vàng" mỗi vài thập kỷ một lần.

Hãy tưởng tượng điều gì xảy ra khi vật chủ từ chối hệ sinh thái:

Đầu tiên, mạng lưới nhân tài bắt đầu rạn nứt. Bạn cần tuyển một Phó Giám đốc Kỹ thuật từng mở rộng công ty từ 25 lên 500 người? Ở San Francisco có 600 ứng viên, ở Boston chỉ có 5 người, và nhanh chóng cả 5 người này cũng sẽ rời Boston đến San Francisco, nơi họ có thể đòi lương cao hơn và xác suất thành công lớn hơn. Với nhân tài cấp thấp hơn, các sinh viên mới ra trường cũng không còn ở lại địa phương – mỗi mùa hè, họ đều bay chuyến đầu tiên ra đi.

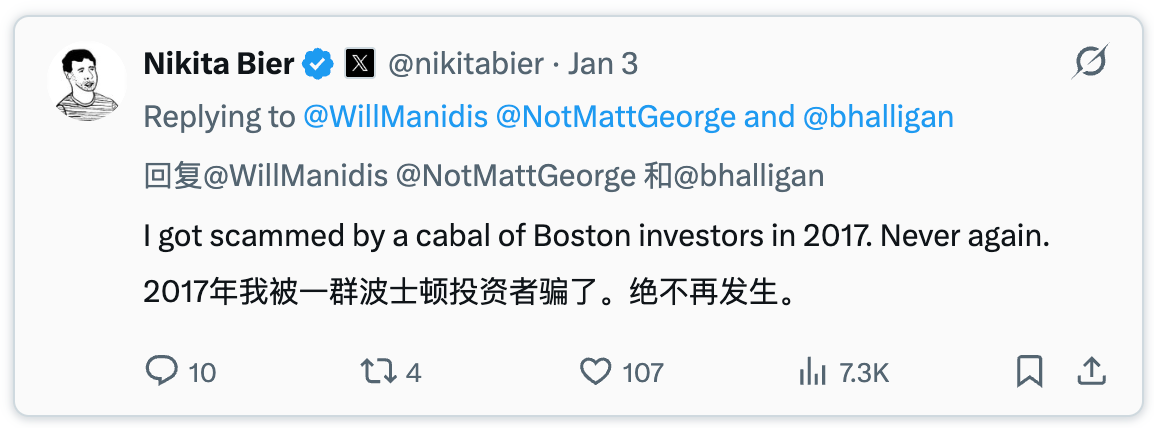

Khi mạng lưới tan rã, chính quyền bang càng siết chặt hơn, cố gắng vắt kiệt cùng một mức lợi nhuận từ những người còn sót lại. Cùng với sự sụp đổ của hệ sinh thái, một số đối tượng thị trường xấu bắt đầu kiếm lợi bằng nhiều cách: ví dụ như định giá ưu đãi ("Ai sẽ bay đến Boston để gọi vốn hạt giống chứ? Được rồi, vậy chúng ta chấp nhận định giá 10 triệu USD"), hoặc bằng những cách tệ hại hơn, chẳng hạn như tống tiền các nhà sáng lập bằng các phương thức phi thị trường hoặc thậm chí bất hợp pháp (có thể tham khảo một số câu chuyện hợp pháp nhưng được công khai trên Twitter từ Nikita và những người khác). Thậm chí một số công ty khởi nghiệp từ Boston khi chuyển đến bờ Tây vẫn duy trì mức độ hành vi "tội phạm có tổ chức" nhất định (trừ Matrix, họ là người tốt).

Những vấn đề này phức tạp, liên quan đến bản chất con người và thực tế. Chúng không chỉ phá hủy thành phố và cuộc sống con người, mà còn khiến hàng ngàn tỷ USD giá trị doanh nghiệp thất thoát – tất cả chỉ vì hành vi thiển cận của chính quyền bang.

Tệ nhất là: Sự mất mát này là không thể đảo ngược.

Dù tôi rất cảm thông với những người kêu gọi phục hưng Boston thành một hệ sinh thái công nghệ vĩ đại – bản thân tôi cũng muốn搬 về, tránh cảnh hỗn loạn ở New York – nhưng tôi khó hình dung phần còn lại của hệ sinh thái sẽ không sụp đổ hoàn toàn.

Bạn không thể cứu một mạng lưới đang sụp đổ bằng luật pháp, cũng không thể khởi động lại một mạng lưới đã tự co lại.

Tuy nhiên, dù là San Francisco hay toàn bộ hệ sinh thái công nghệ Mỹ, dường như đều đang đi theo cùng một con đường: một hệ thống quản lý coi công nghệ như "cây tiền mặt". Ví dụ như Đề xuất M (Prop M – đạo luật hạn chế phát triển bất động sản thương mại), thuế trống văn phòng, v.v.

Đồng thời, một nền văn hóa mắc kẹt trong mạng lưới tinh hoa cũng khó tự giám sát. Trí tuệ nhân tạo (AI) thu hút nhiều đối tượng hành xử xấu vào hệ sinh thái, và sự cứng nhắc mà Boston từng không thể dọn sạch trước đây giờ đang bắt rễ tại đây.

Thêm vào đó là quan điểm tiến bộ kiểu "ưu tiên đầu vào": Chúng ta có phòng thí nghiệm AI tốt nhất, chúng ta có nhiều GPU (bộ xử lý đồ họa) nhất, thậm chí tổng thống còn mua vài chiếc GPU cho chúng ta. Chúng ta có các mô hình tiên tiến nhất. Vậy tại sao lại có vấn đề?

Điểm khác biệt nằm ở cái giá phải trả. Sự sụp đổ của Boston khiến Mỹ mất đi hàng trăm tỷ USD giá trị doanh nghiệp, còn sự suy tàn của San Francisco sẽ xóa sổ một phần ba tăng trưởng GDP của Mỹ trong thập kỷ qua.

Nhưng vấn đề không chỉ là thất bại kinh tế. Đây là một thất bại về sự tồn vong.

Ngành công nghệ của chúng ta đã không thể đưa ra một lý do rõ ràng về sự tồn tại của chính mình ở cấp độ quốc gia. Nếu vấn đề này không được giải quyết, năm 2028 sẽ trở thành một cuộc trưng cầu dân ý về "giam giữ, phá hủy và cướp bóc ngành công nghệ", với ngòi nổ là các cáo buộc về nước và năng lượng.

Ngày nay, hình ảnh của cơn sốt AI trong tâm trí công chúng không hề mơ hồ. Khảo sát gần đây cho thấy người Mỹ bình thường cho rằng trí tuệ nhân tạo là thứ lãng phí tài nguyên nước, đẩy chi phí năng lượng lên cao,换来 lại là lừa đảo người già, truyền bá nội dung tình dục xấu cho trẻ em, quảng bá cá cược thể thao và vô số tội ác khác.

Nếu câu trả lời tốt nhất của chúng ta cho câu hỏi "Tại sao không nên giam giữ các CEO công nghệ, đốt trung tâm dữ liệu và phá hủy ngành công nghệ Mỹ" là: "Để chúng tôi có thể xây dựng chatbot tốt hơn cho cá cược thể thao của bạn", thì cử tri sẽ không do dự khi bỏ phiếu ủng hộ những hành động đó.

Trong một thế giới trò chơi zero-sum, cử tri sẽ không nghĩ đến lợi ích dài hạn; họ sẽ cảm thấy ghen tị trước, rồi bắt đầu cướp bóc. Chúng ta sẽ không cướp hệ thống xử lý nước thải hay lưới điện, bởi vì chúng ta biết đó là hàng rào ngăn hỗn loạn. Chúng ta chấp nhận chi phí của chúng, vì chúng ngăn chặn sự lan tràn của hỗn loạn. Vậy cử tri bình thường có xem công nghệ với vai trò tương tự như vậy không?

Công nghệ là con đường duy nhất giúp chúng ta thoát khỏi bẫy Malthus. Tuy nhiên, vì chúng ta quá hèn nhát để diễn đạt rõ điều này, vì chúng ta thay thế lý thuyết tiến bộ rõ ràng bằng "chủ nghĩa duy lý" và "trí tuệ nhân tạo phổ quát" (AGI), nên nhà nước mới coi ngành công nghệ như một ký sinh trùng có thể tùy ý vắt kiệt.

Nếu chúng ta không thể làm rõ vì sao đổi mới là điều cần thiết về mặt đạo đức, thì chúng ta sẽ chỉ có thể chứng kiến toàn bộ ngành công nghệ đi theo vết xe đổ của Boston: bị đánh thuế trước, rồi bị cướp bóc, và cuối cùng bị kiệt quệ. Đến lúc đó, chúng ta sẽ chỉ có thể thắc mắc đầy bối rối: Tất cả đã đi đâu mất rồi?

Trong một thế giới trò chơi zero-sum, cử tri sẽ không nghĩ đến lợi ích dài hạn; họ sẽ cảm thấy ghen tị trước, rồi bắt đầu cướp bóc. Chúng ta sẽ không cướp hệ thống xử lý nước thải hay lưới điện, bởi vì chúng ta biết đó là hàng rào ngăn hỗn loạn. Chúng ta chấp nhận chi phí của chúng, vì chúng ngăn chặn sự lan tràn của hỗn loạn. Vậy cử tri bình thường có xem công nghệ với vai trò tương tự như vậy không?

Công nghệ là con đường duy nhất giúp chúng ta thoát khỏi bẫy Malthus. Tuy nhiên, vì chúng ta quá hèn nhát để diễn đạt rõ điều này, vì chúng ta thay thế lý thuyết tiến bộ rõ ràng bằng "chủ nghĩa duy lý" và "trí tuệ nhân tạo phổ quát" (AGI), nên nhà nước mới coi ngành công nghệ như một ký sinh trùng có thể tùy ý vắt kiệt.

Nếu chúng ta không thể làm rõ vì sao đổi mới là điều cần thiết về mặt đạo đức, thì chúng ta sẽ chỉ có thể chứng kiến toàn bộ ngành công nghệ đi theo vết xe đổ của Boston: bị đánh thuế trước, rồi bị cướp bóc, và cuối cùng bị kiệt quệ. Và chúng ta sẽ thắc mắc đầy bối rối: Tất cả đã đi đâu mất rồi?

Chào mừng tham gia cộng đồng chính thức TechFlow

Nhóm Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

Tài khoản Twitter chính thức:https://x.com/TechFlowPost

Tài khoản Twitter tiếng Anh:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News