Deep Decoding a16z: Why Do Top Founders Willingly "Sell" Themselves to This Firm?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Deep Decoding a16z: Why Do Top Founders Willingly "Sell" Themselves to This Firm?

a16z is working for the future.

Author: Packy

Translation: TechFlow

Hello friends,

Happy Friday! Today, let’s talk about a16z.

Today, a16z announced the closing of $15 billion in new funds.

To mark the occasion, I’ve decided to write a deep dive on this firm. I interviewed general partners (GPs) and limited partners (LPs) at a16z, founders from a portfolio managing around $200 billion in assets, reviewed documents and pitch decks, and analyzed fund return data since a16z’s inception (see disclosures in the appendix at the end).

The internet is full of critiques of a16z—chances are you’re already familiar with the controversies that have followed the firm since its founding.

But rather than dwell on those criticisms, I want to explore: what are these smart people who've correctly predicted the future actually doing now?

To be clear, I’m not a fully neutral observer. While I don’t have an a16z.com email address, my perspective is still subjective.

For over two years, I served as an advisor to a16z Crypto (I currently receive no compensation). Marc Andreessen and Chris Dixon are LPs in Not Boring Capital. I occasionally co-invest with a16z. I have friendly relationships with many at a16z and most members of their new media team. I collaborate with them, admire them, and respect them.

But we don’t need me to judge whether a16z’s current investment logic deserves backing. Professional institutional LPs have already answered that with $15 billion. It will take ten years to know if they were right—and neither I nor any critic can change that outcome, just as in the past.

What I hope to offer is a unique lens through which to understand what a16z truly is. I believe a16z is one of venture capital’s best marketers—not just because it tells stories, but because its actions align tightly with its narrative. What it says externally matches exactly what it teaches internally. Its pitch has remained consistent since its first fundraising memo. And you can evaluate it yourself via returns data.

There are many excellent venture firms and investors whose strategies and successes gradually become better understood.

But what a16z does is different—bigger, bolder. It doesn’t even feel like traditional venture capital. That’s partly because I don’t think a16z cares whether it’s doing “venture.” Its goal is to build the future and eat the world.

Let’s begin.

a16z: Power Broker

“Live in the future, now is the past,

My presence is a present, kiss my ass.” —Kanye West, “Monster”

Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) hears you.

You say it’s too loud and should “shut up and do its job” politically. You disagree with one or two recent investments. You think quoting the Pope in a tweet isn't appropriate. You think its fund sizes are so massive they can’t possibly deliver reasonable returns to LPs.

a16z has heard all this—for nearly two decades.

Just like when Tad Friend of The New Yorker sat down for breakfast with Marc Andreessen in 2015 while writing “Tomorrow’s Advance Man.” Friend had just heard from a competing VC that a16z’s funds were too large and ownership stakes too small—that to achieve 5–10x total returns on its first four funds, the portfolio would need to be worth between $240 billion and $480 billion.

“When I tried to discuss these numbers with Andreessen,” Friend wrote, “he waved his hand dismissively and said, ‘Bullshit, bullshit. We have all the models—we’re hunting elephants!’”

I want you to keep that image in mind as you brace for your likely reaction to the next paragraph.

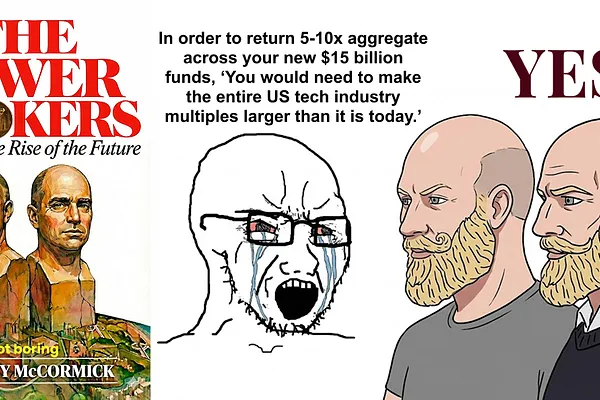

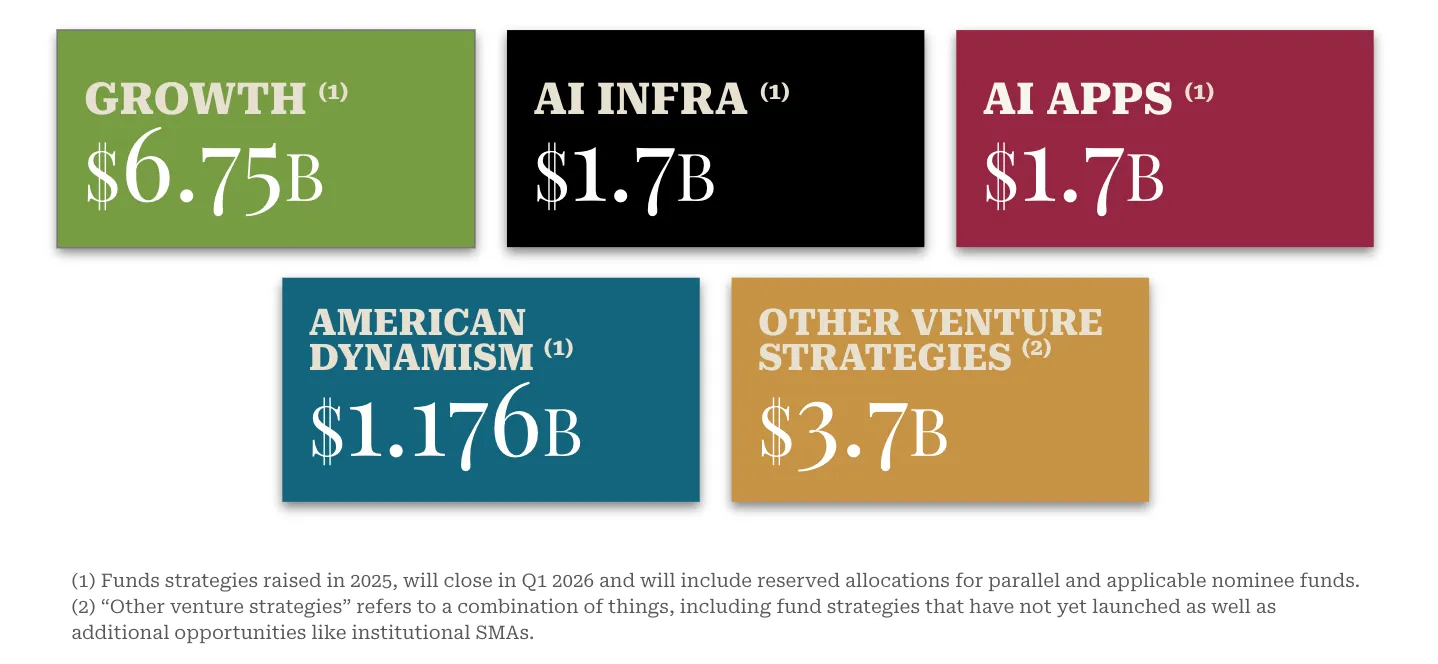

Today, a16z announced it has raised $15 billion across all its investment strategies, bringing its total regulatory AUM to over $90 billion.

In 2025, where venture fundraising was dominated by a few big players, a16z’s raise exceeded the combined totals of Lightspeed ($9B) in second place and Founders Fund ($5.6B) in third.

In one of the worst venture fundraising markets in five years, a16z captured over 18% of U.S. venture fundraising in 2025. In a year when the average venture fund took 16 months to close, a16z did it in just over three months.

If broken out individually, each of a16z’s four separate funds would rank among the top ten largest raises of 2025: Late Stage Venture (LSV) V in second, Fund X AI Infra and Fund X AI Apps tied for seventh, American Dynamism (AD) II in tenth.

Some might say that’s way too much money for a venture firm—so large that expecting outsized returns seems impossible. To that, I imagine a collective a16z hand wave and “bullshit, bullshit”—because it’s still hunting elephants!

Today, across all funds, a16z is an investor in 10 of the 15 highest-valued private companies: OpenAI, SpaceX, xAI, Databricks, Stripe, Revolut, Waymo, Wiz, SSI, and Anduril.

Over the past decade, a16z invested in 56 unicorns through its funds—more than any other VC.

Its AI portfolio accounts for 44% of global AI unicorn enterprise value—again, more than any other firm.

From 2009 to 2025, a16z led 31 early rounds that ultimately reached $5B+ valuations—50% more deals than the next two closest competitors combined.

It has all the models—and now, it has the track record.

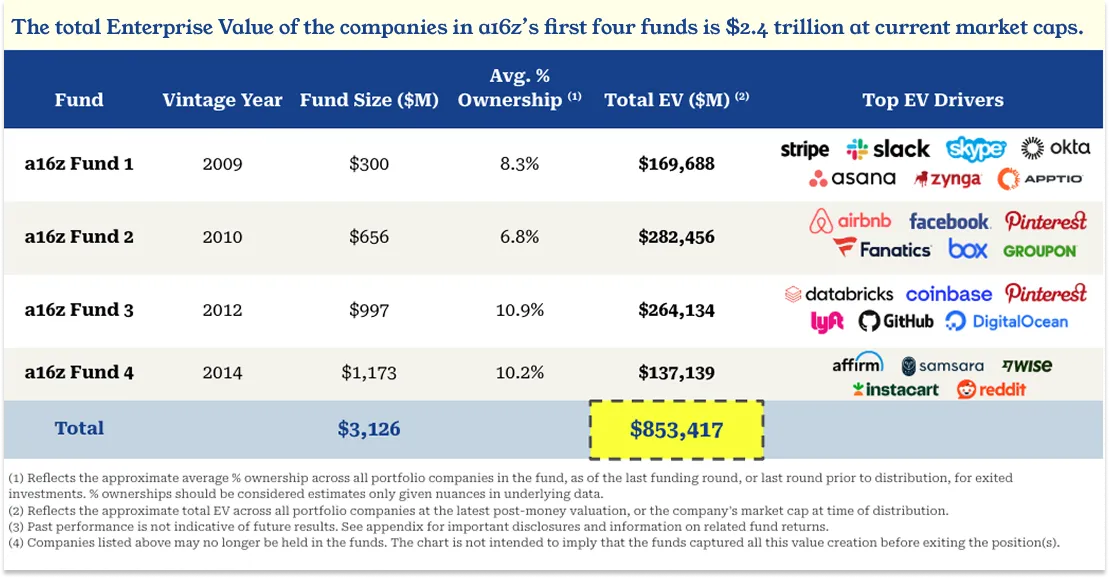

Here’s the total portfolio value of a16z’s first four funds—the same funds that rival VCs thought needed to reach $240B–$480B in value to break even. Ultimately, a16z Funds 1–4 achieved a total enterprise value of $853 billion at distribution or latest late-stage valuation.

And that was at distribution. Facebook alone has added over $1.5 trillion in market cap since then!

This pattern keeps repeating: a16z makes bold, seemingly “crazy bets” on the future, industry insiders mock the decisions as foolish—and a few years later, they turn out not to be foolish, but visionary.

In 2009, post-financial crisis, a16z raised a $300M first fund proposing to support founders via an operating platform. “We talked to a lot of our VC friends, and most thought it was a stupid idea and advised against it. They said it had been tried before and didn’t work,” Ben (Ben Horowitz) recalled. Today, nearly every major VC has its own platform team.

That same year, a16z used $65M from that fund, alongside Silver Lake and others, to buy Skype from eBay for $2.7B. “Everyone said the deal couldn’t close due to IP risk” (eBay was litigating with Skype’s founders over tech rights). Less than two years later, Microsoft bought Skype for $8.5B—proving a16z right.

In September 2010, Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz raised a $650M second fund (Fund II), making large late-stage bets on Facebook ($50M at $34B), Groupon ($40M at $5B), and Twitter ($48M at $4B), betting IPO markets would reopen. At the time, a Wall Street Journal article titled “A Venture-Capital Newbie Shakes Up Silicon Valley” noted rivals criticizing a16z’s strategy—private equity wasn’t supposed to be traditional VC work, and “secondary markets” weren’t even discussed. Benchmark partner Matt Cohler said: “You can make money investing in pork bellies and oil futures—but that’s not what we do.”

Time proved a16z right:

- November 2011: Groupon IPO’d at $17.8B valuation.

- May 2012: Facebook IPO’d at $104B valuation.

- November 2013: Twitter IPO’d at $31B valuation.

In January 2012, Marc and Ben raised a $1B third fund (Fund III) and a $540M parallel opportunities fund. Now, criticism shifted to size. a16z’s fund represented 7.5% of total U.S. VC fundraising in 2012—a weak year for venture. Cambridge Associates showed average VC returns at 8.9%, far below the S&P 500’s 20.6%. Legendary VC Bill Draper said: “The general consensus in Silicon Valley is that too many funds are chasing too few really good companies.” Sounds familiar today.

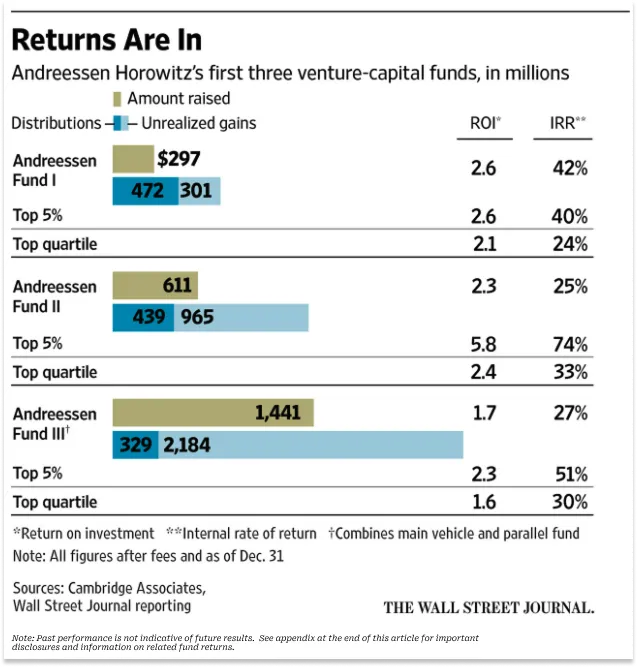

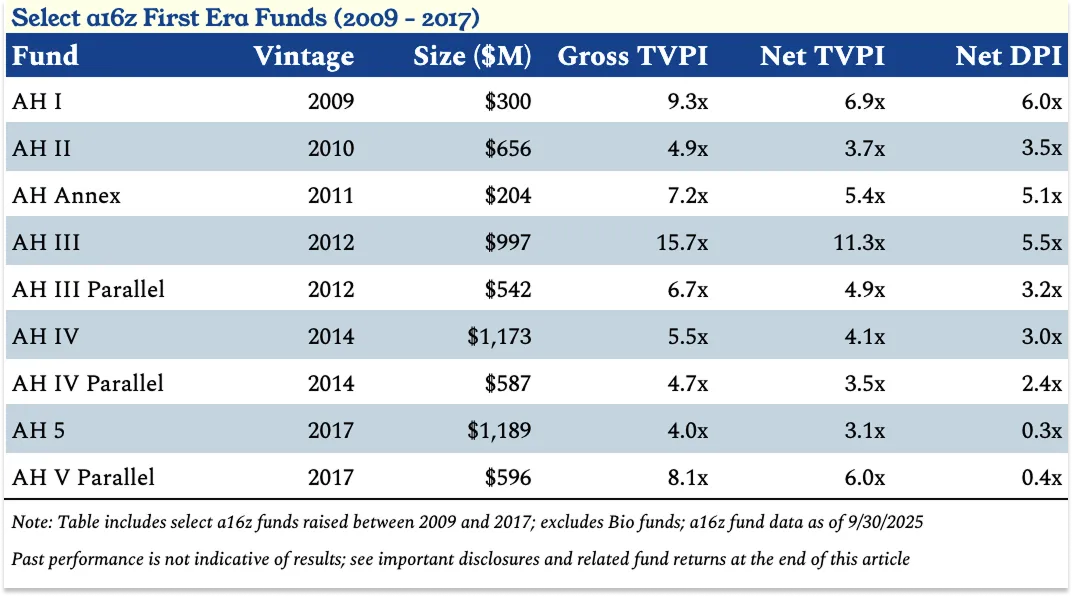

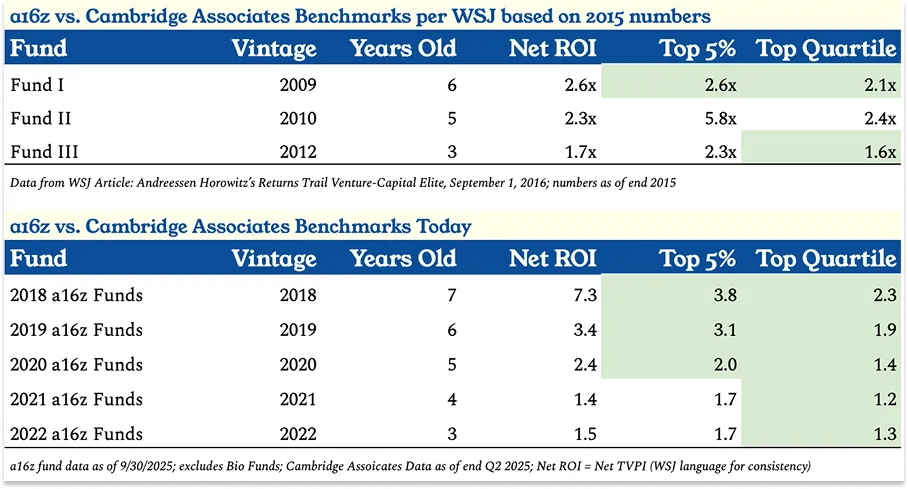

In 2016, The Wall Street Journal published “Andreessen Horowitz’s Returns Lag Behind VC Elite,” which Acquired’s David Rosenthal called “obviously a hit piece cooked up by rival VCs.” It noted a16z’s first three funds—aged 7, 6, and 4 years—had AH Fund I in the top 5%, AH II in the top quartile, and AH III slightly behind the top quartile.

In hindsight, that critique looks especially ironic—AH III is now a monster fund: as of September 30, 2025, net TVPI (total value to paid-in capital, after fees) was 11.3x, or 9.1x including parallel funds.

The fund includes Coinbase (delivering $7B in gross returns to a16z LPs), Databricks, Pinterest, GitHub, and Lyft (though it missed Uber, proving omission may hurt more than error). This could be one of the best-performing large VC funds ever.

Since Q3 2025, Databricks (now a16z’s largest holding) hit a $134B valuation—making AH III look even better (assuming other holdings haven’t depreciated). a16z has distributed $7B in net proceeds from AH III and its parallel fund to LPs, with nearly as much unrealized upside remaining.

Most unrealized value comes from Databricks—a big data company. In 2016, when WSJ questioned a16z, Databricks was pre-$500M. Today, it represents 23% of a16z’s total NAV (net asset value) across all funds.

Inside a16z, you hear Databricks mentioned often. It’s not just a16z’s biggest holding—it’s one of the largest single positions in venture history. Databricks’ journey exemplifies a16z’s playbook.

The a16z Databricks Success Formula

Before diving into Databricks, here are key things to understand about a16z:

- Engineer Culture: Founders and leaders are engineers, shaping how the firm designs itself (around scale and network effects) and selects markets and companies.

- No Second Place: The cardinal sin at a16z is betting on #2. If you miss the early winner, you can catch up later—but betting on #2 risks missing the ultimate winner, even if it hasn’t emerged yet.

- Bet Big on Winners: Once a category winner is identified, a16z’s classic move is to write unexpectedly large checks—often mocked externally.

These principles were set from day one.

In the early 2010s, “big data” was hot in VC circles, centered on Hadoop. Hadoop used MapReduce (a Google-developed programming model) to distribute computing across cheap server clusters instead of expensive hardware. It “democratized big data,” spawning companies like Cloudera and Hortonworks. Yet despite the hype, a16z stayed away.

Ben Horowitz—the “z” in a16z—didn’t like Hadoop. Before becoming CEO of LoudCloud/OpsWare, Ben, a computer science grad, didn’t see Hadoop as the future architecture. Hadoop was notoriously hard to program and manage, and Ben believed it wouldn’t meet future needs: every step in a MapReduce workflow required writing intermediate results to disk, making iterative workflows like machine learning painfully slow.

So Ben sat out the Hadoopla craze. Marc wasn’t happy. As Jen Kha told me:

“Marc gave Ben a lot of shit back then because Hadoop was everywhere. He said, ‘We fucked up! We completely missed this wave! Huge mistake!’”

Ben replied: “I don’t think this is the next architectural shift.”

Only with Databricks did Ben change his mind. “This might be it,” he said—and went all-in.

Databricks emerged at the perfect time, rooted in UC Berkeley.

Ali Ghodsi’s story began in 1984 during the Iranian Revolution. He and his family fled Iran for Sweden. His parents bought him a Commodore 64, which Ali used to teach himself programming—eventually earning an invitation to UC Berkeley as a visiting scholar.

At Berkeley, Ali joined AMPLab (Algorithms, Machines, and People Lab), one of eight researchers—including mentors Scott Shenker and Ion Stoica—working to realize PhD student Matei Zaharia’s thesis and develop Spark, an open-source engine for big data processing.

Their goal: “recreate what big tech did with neural nets, but without the complex interface.” Spark set world records in data sorting, and Matei’s thesis won Best CS Dissertation. True to academic tradition, they released Spark’s code for free—but almost nobody used it.

So starting in 2012, the eight researchers met frequently and eventually decided to found a company based on Spark. They named it Databricks. Seven joined as co-founders; Shenker became an advisor.

Image: Databricks Cofounders - Ali Ghodsi seated front-middle, Forbes

The Databricks team initially thought they needed some funding—not much, just a little. As Ben recalled to Lenny Rachitsky:

“When I met them, they said, ‘We need to raise $200K.’ I knew they had something called Spark, and Hadoop was the competitor. Hadoop already had well-funded companies pushing it, and Spark was open-source—time was short.”

He also realized academics might lean toward modest outcomes. “Professors… if you start a company and make $50M, that’s huge. You’re a hero on campus,” he told Lenny.

Ben delivered bad news: “I won’t write you a $200K check.”

But good news: “I’ll write you a $10M check.”

His reasoning: “If you’re going to start a company, you need to really do it. Go big. Otherwise, stay in school.”

They dropped out. Ben increased the investment. a16z led Databricks’ Series A at a $44M post-money valuation, taking 24.9%.

This initial interaction—Databricks wanted $200K, a16z offered $10M—set a pattern: when a16z invests in you, it truly believes in you.

When I asked about a16z’s impact, Ali was blunt: “Without a16z, Databricks probably wouldn’t exist today. Especially Ben—I don’t think we’d have made it this far. They genuinely believed in us.”

In year three, Databricks had only $1.5M in revenue. “Success was far from certain,” Ali recalled. “The only person who truly believed we could do something big was Ben Horowitz. He believed more than we did. Honestly, more than I did. That’s on him.”

Belief is cool. But belief becomes more powerful when you can make it self-fulfilling.

Like in 2016, when Ali tried to secure a partnership with Microsoft. Given Azure’s strong demand, he assumed the deal was guaranteed. He asked several VCs to introduce him to Satya Nadella—introductions happened, but got “buried in assistant workflows.”

Then Ben formally introduced Ali to Satya. “I got an email from Satya saying, ‘We’re very interested in building a very deep partnership,’” Ali recalled. “He copied his deputies—and their deputies. Within hours, my inbox had over 20 emails from Microsoft employees I’d previously failed to reach. Now they were asking, ‘When can we meet?’ I knew then—this time it’s different. This will happen.’”

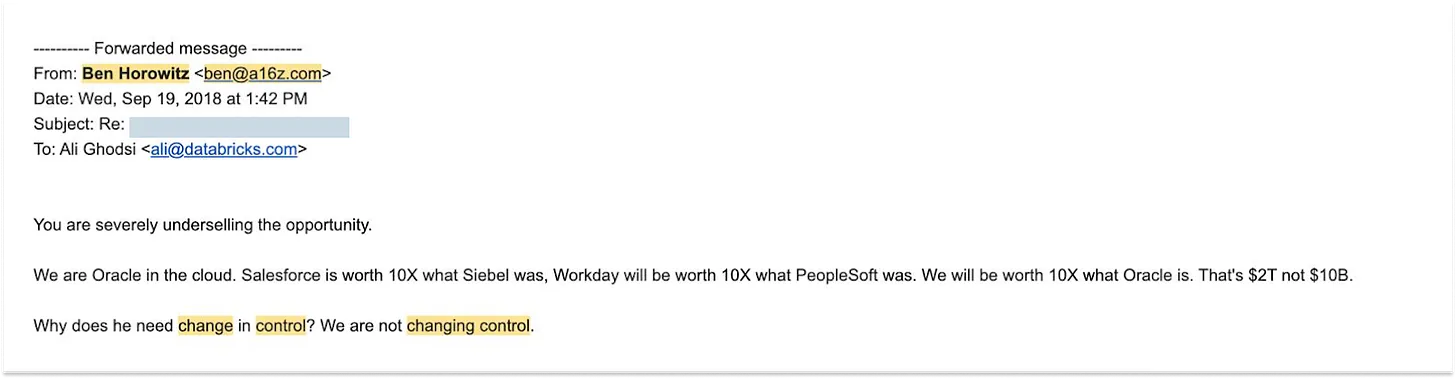

Or in 2017, when Ali wanted to hire a senior sales exec. The candidate requested a change-of-control clause—accelerated vesting upon acquisition.

This became critical, so Ali asked Ben to convince the executive that Databricks was “worth at least $10B.” After talking with him, Ben emailed Ali:

Image: Ben Horowitz Email to Ali Ghodsi, September 19, 2018 courtesy of Ali Ghodsi

“You're severely underestimating the opportunity.

We are Oracle in the cloud. Salesforce is 10x Siebel's market cap. Workday will be 10x PeopleSoft. Our market cap will be 10x Oracle's. This isn't $10B—it's $2T.

Why does he need change of control? We won't be changing control.”

Possibly one of the hardest business emails ever sent—especially given Databricks was then valued at $1B with $100M in annual revenue. Today, it’s worth $134B with over $4.8B in revenue.

“They saw the full potential,” Ali told me. “When you’re deep in the weeds, running the company daily, you see challenges—deals fall through, competitors beat you, cash runs low, no one knows you, employees leave—it’s hard to think that way. But they come into board meetings and say, ‘You’re going to conquer the world.’”

They were right—and their belief was rewarded. Overall, a16z participated in all 12 Databricks rounds and led four. The company was key to AH 3’s success and a major driver of returns in Late Stage Ventures Funds 1, 2, and 4.

“First, they really care about the mission. I don’t think Ben and Marc see it primarily as a financial return issue. That comes second,” Ali said. “They’re believers in technology, wanting to use it to change the world.”

If you don’t grasp Ali’s view of Marc and Ben, you can’t truly understand a16z.

What Is a16z?

a16z isn’t a traditional venture fund. Obvious, right? It just completed the largest VC raise since SoftBank’s $98B Vision Fund in 2017 and Vision Fund II in 2019. But even SoftBank’s Vision Fund is still one fund—while a16z is more than that.

Sure, a16z raises funds and generates returns for LPs. So far, it’s excelled at this. Later, I’ll share a16z’s fund return data.

But first—what exactly is a16z?

a16z is a “faith movement” around technology. Everything it does aims to advance better tech and create a better future. It believes “technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the vanguard of progress, the realization of potential.” From this faith, everything a16z does revolves around betting on the future.

a16z is a “firm,” not just a “fund.” It aims to grow stronger through scale. Unlike funds, which aim to maximize returns with minimal people and time, a firm seeks superior returns while building compounding competitive advantages. As a16z GP David Haber explained: “A fund wants to make the biggest return with the fewest people in the shortest time. A firm wants to deliver great returns while building sustainable competitive advantage. We ask: How do we get stronger as we grow, not weaker?”

a16z is run by engineers and entrepreneurs. Traditional capital managers try to claim bigger slices of a fixed pie; engineers and entrepreneurs expand the whole pie by building and scaling better systems.

a16z is a “temporal sovereign” for the future. At its most ambitious, a16z sees itself as a peer to top global financial institutions and governments. It once said its goal was to be the JP Morgan of the information age—but that may undersell its true ambition. If governments serve a geographic territory, a16z serves the temporal territory of the future. Venture capital is simply the way it discovered to exert maximum influence on the future—and the business model most aligned with that impact.

a16z’s mission is to create and transfer “power.” It builds power through scale, culture, network, organizational infrastructure, and success stories—then transfers it to portfolio startups via sales, marketing, hiring, and government relations. Founders often say a16z will do anything it can for its companies—and it seems capable of a lot.

If you were designing an institution—one that believes “technology is eating larger markets than ever,” that “everything is technology”—you’d build a company capable of giving hundreds or thousands of startups “the power to win.” That institution might look like a16z.

Firms that could become economic pillars often start small and fragile. They’re scattered, diverse, sometimes competing. Meanwhile, they face incumbent giants unwilling to cede market share.

A small company, no matter how promising, can’t afford to hire top recruiters to attract elite engineers and executives. It can’t advocate for fair policies or command attention to tell its story. It lacks legitimacy to sell to governments and enterprises.

For any single startup, spending billions to build these capabilities solely for itself makes no sense. But if these costs are shared across all potential companies and cover future trillions in market value, small startups can access big-company resources. Then, their success depends on product quality, not resource disparity. They gain the ability to bring the future forward as it should be.

What happens if you combine a startup’s agility and innovation with the power and influence of a “temporal sovereign”?

That’s what a16z has aimed for since it was a startup itself.

Why Marc and Ben Founded a16z: From Market Insight to Industry Disruption

In June 2007, Marc published “The Only Thing That Matters” on his Pmarca Guide to Startups blog. Ostensibly advice for tech startups, viewed today it reads more like a16z’s founding manifesto. Marc explored the three core elements of startup success—team, product, or market—and which mattered most.

Entrepreneurs and VCs say team. Engineers say product.

Marc chose the third: “I personally believe market is the single most important factor determining startup success.”

Why Market?

He wrote:

“In a great market—a large market with real customers—market pulls product out of startups...

Conversely, in a poor market, even the best product and strongest team won’t save you—you’re doomed...

In homage to Andy Rachleff of Benchmark Capital (who crystallized this insight), let me state the ‘Rachleff Theory of Startup Success’:

The number one cause of startup failure is lack of market.

Andy put it this way:

- When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins.

- When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins.

- When a great team meets a great market, magic happens.

I think Marc and Ben saw in venture capital a massive market (no one realized how big) filled with terrible teams (no one realized how bad).

Between 2007 and 2009, Marc and Ben pondered their next move. As wildly successful tech entrepreneurs, they were wealthy and driven. Their success gave them freedom to choose their path.

But how?

As entrepreneurs and angel investors, they’d encountered “bad VCs” and found competing against them potentially fun.

“For Marc, from my perspective, this wasn’t about money,” a16z GP David Haber told me. “He’s been rich since he was 20. At first, it was more about ‘fucking up Benchmark or Sequoia’s faces.’”

Yet venture had another advantage, rarely appreciated during the 2008 financial crisis recession: it might be the greatest market of all. That mattered deeply to Marc.

Not all VCs performed poorly. The two firms Marc wanted to “f*ck up”—Sequoia and Benchmark—were actually excellent (Marc even quoted Andy Rachleff!). But they tended to strip founders of control. For founders wanting to retain control, Peter Thiel founded Founders Fund in 2005 and launched FF II in 2007, which ultimately returned $18.60 in cash for every $1 invested (DPI).

Still, compared to today, venture overall felt sluggish, closed-off—a craft guild.

Marc loves telling a story from 2009 when he and Ben considered founding a16z. He met a top VC GP who compared startup investing to grabbing sushi off a rotating conveyor belt. Marc recalled the GP saying:

Venture capital is like going to a sushi boat restaurant. You just sit on Sand Hill Road in Silicon Valley, and startups come to you. If you miss one, no problem—another boat is coming. You just sit, watch the plates go by, and occasionally grab one.

That works fine if ambitions are limited, Marc explained in an interview with Jack Altman on Uncapped: “As long as the industry’s ambitions are capped, that model holds.”

But Marc and Ben’s ambitions were never capped. In their world, the greatest “sin” was “missing an opportunity”—not investing in a great company. This was crucial because they saw tech giants growing larger with market expansion.

“Ten years ago, there were roughly 50 million internet users, few with broadband,” Ben and Marc wrote in April 2009 in the Andreessen Horowitz Fund I fundraising memo. “Now, about 1.5 billion people are online, many with broadband. Thus, both consumer and infrastructure winners can be vastly larger than previous-generation tech companies.”

Meanwhile, launching a company had become dramatically cheaper and easier—meaning many more would emerge.

They wrote to potential LPs: “The cost to develop a new tech product and at least test it has plummeted. Now typically $500K–$1.5M, versus $5M–$15M over a decade ago.”

Finally, as companies evolved from tools to direct competitors with traditional businesses, their ambitions grew. Every industry would become a tech industry—and thus larger.

Why Was the Market So Good Then?

Marc continued:

“From the 1960s to 2010, venture had a fixed playbook… companies were basically toolmakers, right? Pick and shovel makers. Mainframes, desktops, smartphones, laptops, internet access software, SaaS, databases, routers, switches, disk drives, word processors—all tools.

But by 2010, the industry permanently changed… tech’s biggest winners increasingly cut directly into traditional industries.”

Was a16z paying too much for startups back then—or pricing them reasonably relative to future potential?

Hindsight shows the latter was clearly correct. Impressively, a16z saw this early.

As they wrote, roughly 15 tech companies annually reach $100M in revenue, typically capturing 97% of that year’s cohort’s public market value—today’s “Power Law.” Thus, a16z must fight to participate in as many potential winners as possible and double or triple down on them.

To do this, a16z needed to rethink how to build a firm, not just a fund—with only two investing partners.

When sharing basic terms for AH I Fund (target $250M, GPs committing $15M), Ben and Marc summarized their firm strategy in one paragraph.

This strategy remains active—even as a16z has far surpassed two partners and the original “top five” goal.

The Three Eras of a16z

Since its first fund, a16z’s core competitive advantage has been extraordinary conviction and asymmetric confidence in the future. This belief isn’t just a differentiator—it’s the source of all other advantages.

As a16z’s ambition, resources, fund size, and influence grew, so did how it applied this advantage and its differentiation strategy.

Era One (2009–~2017)

In a16z’s first era (2009–~2017), the core insight was: if “software is eating the world,” the best software companies would be worth far more than market valuations suggested.

This belief enabled three strategies to leap from newcomer to “top five”:

- Bet at High Prices

As mentioned, a16z made early trades seen by many as overpriced or non-traditional VC. On the Acquired podcast, Ben Gilbert noted: “The common critique was they overpaid to get into winning deals—or to buy fame.” But he added it was rational then. “Does anyone today think any of their 2009–2015 investments were overvalued? Absolutely not.” As Ben Horowitz explained in a 2014 Harvard Business School case study: “Even billion-dollar valuations may still undervalue a company’s potential.” That’s a16z’s edge.

- Build Operating Infrastructure Seen as ‘Wasteful’

a16z built full-service teams, recruiting partners, corporate briefing centers—extras that looked like fund manager luxuries. But if you believe portfolio companies will define categories and need enterprise-grade resources to land Fortune 500 deals, such spending makes sense. They were preparing for a future where startups must look like real big companies.

- Treat Technical Founders as Scarce Resources

a16z bet that as companies became cheaper and easier to launch, technically gifted founders without traditional management experience would launch more important companies. So a16z went all-out to attract and support these founders, importing CAA’s (Creative Artists Agency) model to venture. “Founder-friendly” is now industry-wide—but back then, it was novel.

In Era One, the main goal was picking the right companies and profiting from their expected success. Though focused on helping founders, they mainly exploited arbitrage opportunities in the market.

AH III stood out for Coinbase and Databricks—but more notable was its sustained performance.

David Clark, CIO at VenCap, said: “As LPs, we’re happy with consistent [net] 3x [TVPI] returns and occasional [net] 5x+. That’s exactly what a16z delivered. Few firms scale while consistently delivering this.” Data bears this out.

If Era One’s high-price investing was a long-term return strategy, it seemed to carry little short-term cost.

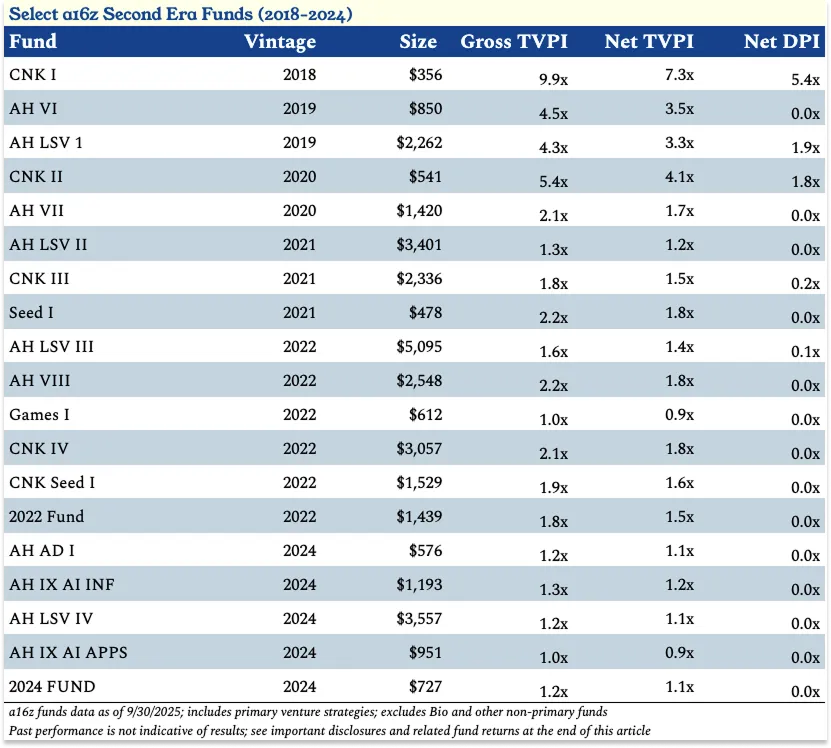

Era Two (2018–2024): From Top 5 to Industry Leader

In a16z’s second era (2018–2024), the core belief was: tech winners would be bigger than anyone expected, stay private longer, and tech would eat more industries—realizations not yet fully grasped.

This belief enabled three moves to jump from “Top 5 VC” to industry leader:

Raise Larger Funds

In Era One, a16z raised $6.2B across nine funds. In Era Two, in just five years, it raised $32.9B across 19 funds. Conventional VC wisdom says larger funds suffer lower returns. a16z disagreed: if the biggest returns are growing, you need more capital to maintain meaningful ownership across multiple rounds. Marc often says: “You can lose at most 1x your money, but your upside is nearly infinite.”

Break the Single-Fund Model, Embrace Diversification

In Era One, a16z raised core funds and late-stage follow-on funds, with all GPs investing from the same fund (though focusing on different areas). It also raised a dedicated bio fund, as biotech was distinct.

In Era Two, a16z decentralized.

- 2018: Launched first crypto-dedicated fund CNK I, led by Chris Dixon.

- 2019: Recruited David George to lead Late Stage Ventures (LSV) fund, raising LSV I ($2.26B)—nearly twice any prior a16z fund.

- During this period, a16z raised new funds across core, crypto, bio, and LSV strategies, launched a seed fund (AH Seed I, $478M) in 2021 and a games fund (Games I, $612M). In 2022, it debuted a cross-strategy fund ($1.4B 2022 Fund), letting LPs proportionally invest across that year’s funds.

Though funds leveraged centralized resources (like IR teams), each built dedicated platform teams tailored to vertical needs—marketing, operations, finance, events, policy.

Hold Top Company Stakes Longer

In Era Two, leading companies stayed private longer, raising more in private markets—both for growth (primary rounds) and liquidity for employees and early investors (secondaries).

Matt Cohler once likened a16z buying Facebook secondary shares to “investing in pork bellies”—but this became standard. Companies like Stripe, SpaceX, WeWork, and Uber gained public-market-like liquidity in private markets.

This challenged the industry: LPs lacked easy liquidity, disrupting capital allocation cycles. But for firms believing tech would grow larger and willing to hold long-term, it was a godsend. It allowed heavier investment in high-quality private companies, pulling public-market-like returns into private markets earlier. I believe this shift is key to how firms like a16z maintained high returns while scaling.

To adapt, a16z:

- Became a registered investment advisor (RIA), enabling free investment in crypto, public stocks, and secondaries.

- Launched the aforementioned LSV I fund under David George. In Era Two, LSV funds accounted for $14.3B of a16z’s $32.9B raised.

- Split crypto funds in fourth fund into seed ($1.5B) and late-stage ($3B) vehicles.

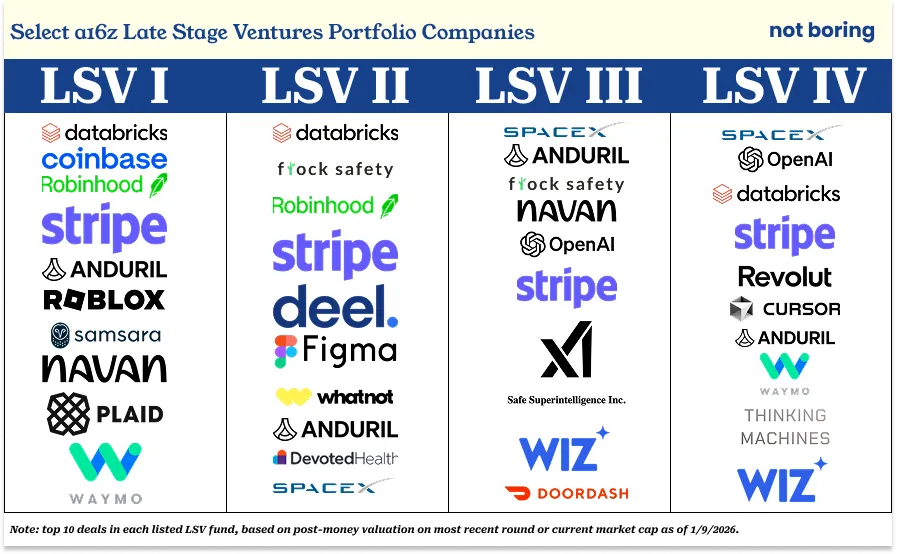

Below are the top ten investments per LSV fund based on latest post-money valuations or current market caps:

LSV I: Coinbase, Roblox, Robinhood, Anduril, Databricks, Navan, Plaid, Stripe, Waymo, Samsara.

LSV II: Databricks, Flock Safety, Robinhood (exited publicly, reinvested gains into more Databricks), Stripe, Deel, Figma, WhatNot, Anduril, Devoted Health, SpaceX.

LSV III: SpaceX, Anduril, Flock Safety, Navan, OpenAI, Stripe, xAI, Safe Superintelligence, Wiz, DoorDash.

LSV IV: SpaceX, Databricks, OpenAI, Stripe, Revolut, Cursor, Anduril, Waymo, Thinking Machine Labs, Wiz.

If a16z was once criticized for “overpaying for marquee logos,” its chosen logos aren’t inferior to anyone’s. According to Cambridge Associates Q2 2025 data, LSV I ranked in the top 5% for its vintage year, LSV II and LSV III in the top quartile for theirs.

As of September 30, 2025, LSV I had a net TVPI of 3.3x, LSV II 1.2x net TVPI (likely higher post recent Databricks and SpaceX rounds), LSV III 1.4x net TVPI (also likely higher after SpaceX’s major secondary at $800B valuation).

By firmly believing top private tech companies’ potential far exceeded most expectations (though not all—e.g., Founders Fund on SpaceX, Thrive on Stripe), a16z could deploy more capital into them.

More importantly, a16z began proving growth-stage funds could achieve venture-like returns under the right conditions. Per analysis by an a16z LP, firms with strong early investment skills, by continuing to invest at growth stages, can achieve not just VC-like multiples but higher IRRs. Plus, deeper relationships boost a16z’s influence.

In Era Two, a16z’s core belief was holding large stakes in winners. Early investment insights plus specialized late-stage funds made doubling down or correcting early misses easier (though still not controlling stakes like other asset classes).

This strategy was essentially arbitrage—but I believe in this era, a16z worked harder to help its portfolio succeed.

Though second-era returns are early, they already outperform first-era funds at similar stages. While first-era funds underperformed early (per WSJ), second-era funds shine:

- 2018 fund: 7.3x net TVPI

- 2019 fund: 3.4x net TVPI

- 2020 fund: 2.4x net TVPI

- 2021 fund: 1.4x net TVPI

- 2022 fund: 1.5x net TVPI

Notably, crypto funds (CNK 1–4 and CNK Seed 1) performed exceptionally. CNK I delivered 5.4x net DPI (distributions to paid-in capital) to LPs.

More surprisingly, despite criticism that a16z’s $3B raise for CNK IV in 2022 was too large and ill-timed, it has achieved a 1.8x net TVPI so far.

The two highlights of Era Two—LSV and crypto funds—reflect a16z’s dual beliefs: LSV responded to longer private lifecycles and greater private-market capital needs. Crypto funds embodied innovation and returns emerging from entirely new domains, not traditional investing.

These highlights also reflected a16z’s expanding role in creating value for portfolio companies and the broader industry. To help late-stage companies thrive, a16z needed to recreate some public-market advantages in private markets. To ensure crypto’s survival in the U.S. and fair competition for all emerging tech against entrenched interests, a16z needed to go to Washington.

a16z’s third-era core belief: emerging tech companies won’t just reshape every industry—they’ll dominate, if given the chance. And a16z must lead the industry and nation in the right direction.

This belief again changed a16z’s essence. With scale (the $15B fund as symbolic inflection), merely “picking winners” wasn’t enough.

a16z must create winners by shaping the competitive landscape.

As Ben said: “It’s time to lead.”

a16z’s Third Era: Time to Lead the Future

In this phase, you can imagine a rival VC analyst texting journalist Tad Friend: “To generate 5–10x total returns on your new $15B fund, the entire U.S. tech sector would need to be several times larger than today.”

And Marc and Ben’s reply, you can imagine: “Exactly.”

This is a16z’s explicit plan, logically structured:

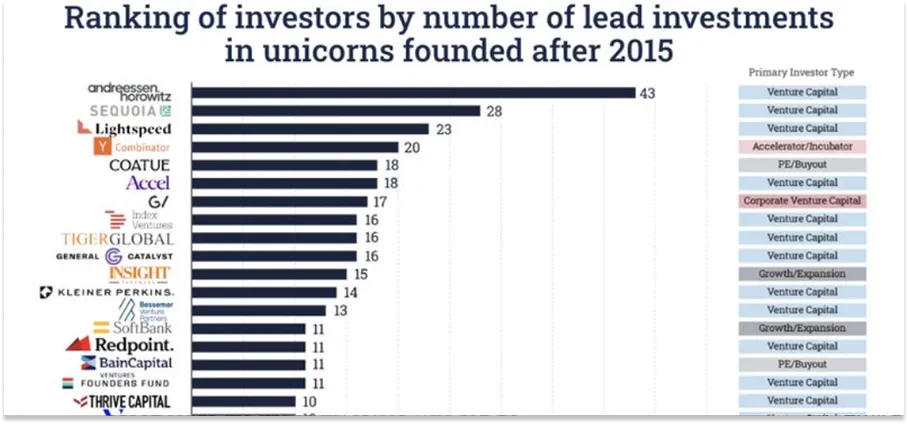

Since 2015, a16z has backed more early-stage unicorns than any other investor—its gap over second-place Sequoia equals Sequoia’s gap over 12th place.

Source: Stanford Professor Ilya Strebulaev

Judging “best VC” by “number of early-stage companies invested in that became unicorns” is a specific, a16z-favorable metric. More common metrics include return multiples, IRR, or total cash distributed to LPs. Others focus on hit rate or consistency. Many ways to slice VC rankings.

Yet this metric seems aligned with a16z’s worldview. In conversations with a16z’s crypto team, I repeatedly heard: betting on a domain because many smart founders explore it—even if wrong—is fine. But picking the wrong company within a domain, or missing the ultimate winner for any reason, is unacceptable. As Ben said:

“We know building a company is inherently risky, so if we followed the right process and assessed risk properly, we don’t worry about losing investments. But if we misjudged whether a founder was the best in her field, we’d be deeply concerned.

If we misjudged an emerging domain, that’s okay. But if we picked the wrong founder, that’s a big problem. And if we missed the right founder, that’s a big problem. Losing a transformative company due to conflict or missed opportunity is far worse than investing in the best founder in a domain we misjudged.”

By a16z’s own measure of “the only thing that matters,” it has become the venture industry leader.

“So what now?” Ben asks. “What does leading an industry mean?”

In the X post announcing the $15B raise, he

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News