IOSG: Pouring cold water on prediction markets

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

IOSG: Pouring cold water on prediction markets

Prediction markets rely on finite and discrete real-world events, making them low-frequency compared to trading.

Author: Jiawei

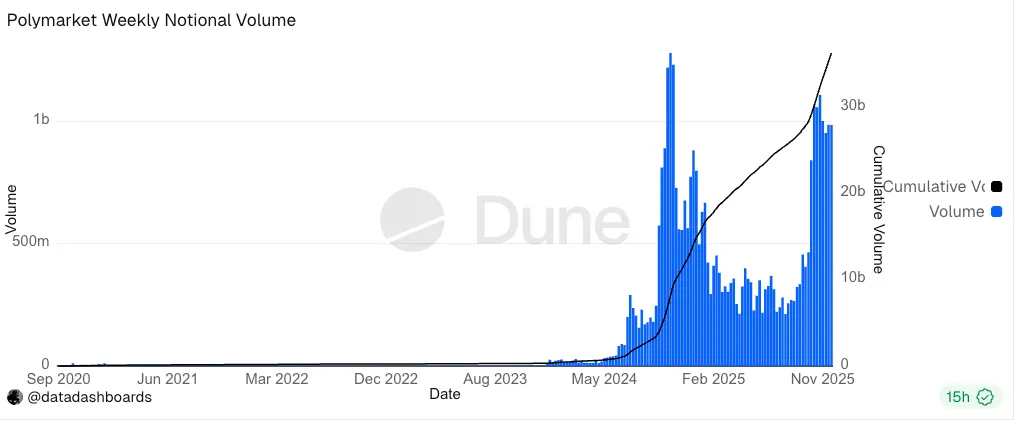

Prediction markets are undoubtedly one of the most watched sectors in the crypto industry. Leading project Polymarket has seen over $36 billion in cumulative trading volume and recently completed a strategic funding round at a $9 billion valuation. At the same time, platforms including Kalshi (valued at $1.1 billion) have also attracted substantial capital investment.

Source: Dune

However, behind the continuous influx of capital and impressive data growth, we find that as a trading product, prediction markets still face many challenges.

In this article, I aim to set aside mainstream optimism and offer some alternative perspectives.

Predictions are event-based—events are inherently non-continuous and non-replicable. Unlike asset prices such as stocks or foreign exchange that change continuously over time, prediction markets rely on finite and discrete real-world events. Compared to trading, they are low-frequency by nature.

In the real world, there are very few events that have broad public attention, clear outcomes, and settlement within a reasonable timeframe—presidential elections occur every four years, the World Cup every four years, the Oscars annually, and so on.

Most social, political, economic, and technological events do not generate sustained trading demand. The number of such events each year is limited and their frequency too low to build a stable trading ecosystem.

In other words, the low-frequency nature of prediction markets cannot be easily altered by product design or incentive mechanisms. This fundamental characteristic means that without major events, trading volume will inevitably remain low.

Prediction markets do not have fundamentals like stock markets: the value in stock markets comes from intrinsic company value, including future cash flows, profitability, assets, etc. In contrast, prediction markets ultimately point toward a single outcome, relying entirely on users’ interest in the event result itself.

(Of course, here we discuss only the original intent of the product, excluding objective arbitrage and speculation factors; even in stock markets, there are many speculators who may not care about the underlying asset’s essence)

Under this context, the amount people are willing to bet correlates strongly with the importance of the event, market attention, and time horizon: rare, high-attention events such as finals and presidential elections attract significant capital and attention.

Naturally, an average fan is far more likely to place a large bet on the annual championship final than on regular-season games.

On Polymarket, the 2024 U.S. presidential election accounted for over 70% of the platform’s total open interest. Meanwhile, the vast majority of events remain in a state of low liquidity and high bid-ask spreads. From this perspective, it is difficult for prediction markets to scale exponentially.

Prediction markets inherently possess gambling-like characteristics but struggle to achieve the same level of user retention and expansion as traditional gambling.

We all know that the real addiction mechanism in gambling lies in instant feedback—slot machines deliver results every few seconds, Texas Hold’em hands take minutes, and contract and memecoin trades shift second by second.

Prediction markets, however, have long feedback cycles; most events require weeks or even months to resolve. Events with faster resolution often aren’t interesting enough to justify large bets.

Immediate positive feedback significantly increases dopamine release frequency, reinforcing user habits. Delayed feedback fails to create stable user retention.

In certain types of events, information asymmetry among participants is extremely high.

For sports-related events, beyond team strength on paper, outcomes heavily depend on athletes’ real-time performance, thus retaining considerable uncertainty.

But for political events, internal information, channels, and connections form a black box process, giving insiders a massive informational advantage and much higher certainty when placing bets.

For example, vote counting procedures, internal polling data, and organizational conditions in key regions are largely inaccessible to outside participants. Currently, no regulatory body has clearly defined "insider trading" within prediction markets, leaving this area in a gray zone.

Overall, parties at an information disadvantage are easily drained of liquidity in such cases.

Due to linguistic ambiguity and definitional vagueness, events in prediction markets can hardly be completely objective.

For instance, whether "Russia and Ukraine cease fire in 2025" depends on which statistical standard is used; whether a "crypto ETF is approved at a given moment" involves nuances such as full approval, partial approval, or conditional approval. This leads to issues of "social consensus"—when two sides are evenly matched, the losing party may refuse to accept the outcome.

This ambiguity necessitates dispute resolution mechanisms on platforms. Once prediction markets confront linguistic vagueness and dispute resolution, they can no longer fully rely on automation or objectivity, creating room for human manipulation and corruption.

The primary value proposition touted for prediction markets is "the wisdom of the crowd"—given low trust in media and mainstream narratives, prediction markets supposedly aggregate the best global information to reach collective consensus.

Yet before achieving massive adoption, such "information sampling" will inevitably be partial and insufficiently diverse. Users on prediction market platforms may be highly homogenous.

For example, in its early stages, a prediction market is likely dominated by cryptocurrency users whose views on political, social, and economic events may be highly aligned, forming echo chambers.

In such cases, the market reflects the collective bias of a specific subgroup, falling short of true "wisdom of the crowd."

Conclusion

The core intention of this article is not to discredit prediction markets, but to encourage maintaining clarity amid heightened FOMO, especially after experiencing the rise and fall of popular narratives such as ZK and GameFi.

Overreliance on special events like elections, short-term social media sentiment, and airdrop incentives often inflates surface-level data, which is insufficient to support long-term growth projections.

Nevertheless, from the standpoint of user education and onboarding, prediction markets will continue to hold an important position over the next three to five years. Similar to on-chain yield-bearing savings products, they feature intuitive interfaces and low learning curves, making them better positioned than on-chain trading protocols to attract users from outside the crypto space. For this reason, prediction markets are likely to further develop and may become gateway products into the crypto ecosystem.

Future prediction markets may also dominate specific verticals such as sports and politics. They will continue to exist and expand, but lack the foundational conditions for exponential growth in the near term. We should therefore adopt a cautiously optimistic lens when considering investments in prediction markets.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News