DeFi Fund Managers: Anonymous Gamblers in a Hundred Billion Dollar Market

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

DeFi Fund Managers: Anonymous Gamblers in a Hundred Billion Dollar Market

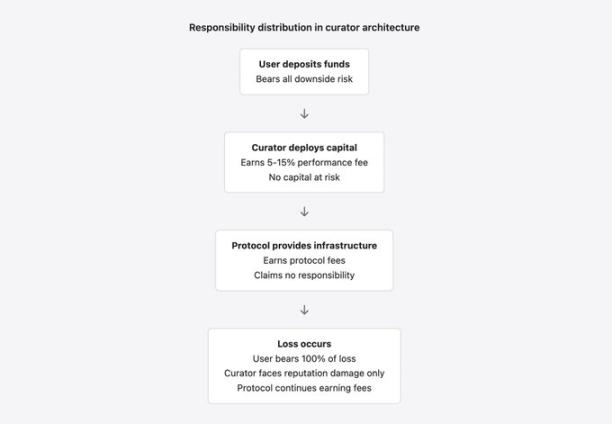

The currently implemented DeFi fund manager model creates an accountability vacuum, with billions of dollars in user funds managed by entities whose actions are effectively unconstrained and whose failures carry no real consequences.

Author: YQ

Translation: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

The Rise of DeFi Fund Managers

Over the past year and a half, a new type of financial intermediary has emerged in the DeFi space. These entities call themselves "risk managers," "treasury operators," or "strategy curators." They manage billions of dollars in user deposits on protocols such as Morpho (around $7.3 billion) and Euler (around $1.1 billion), responsible for setting risk parameters, selecting collateral types, and deploying yield strategies. They take 5% to 15% of generated returns as performance fees.

However, these entities operate without licenses, oversight, mandatory disclosure of qualifications or track records, and often conceal their true identities.

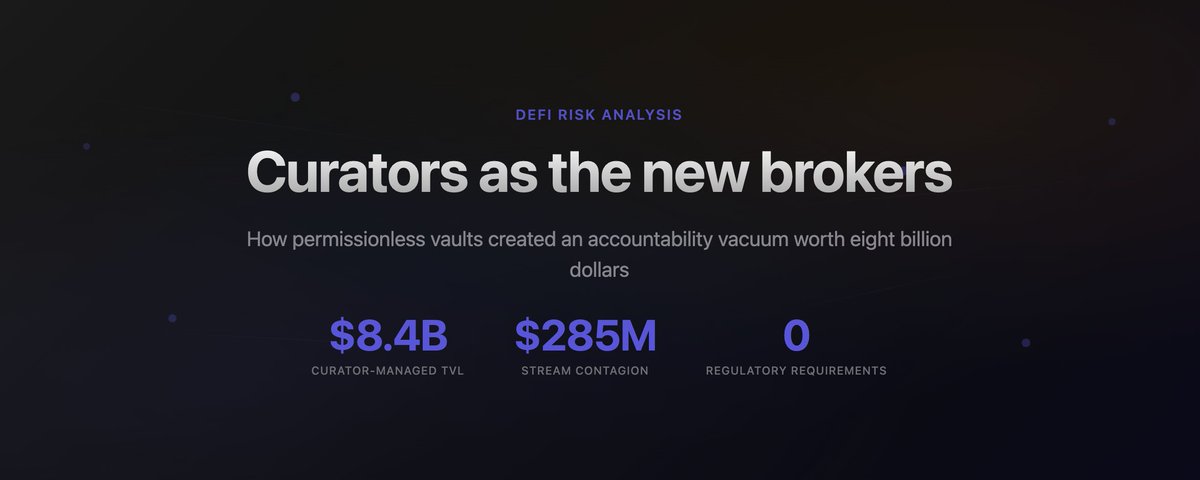

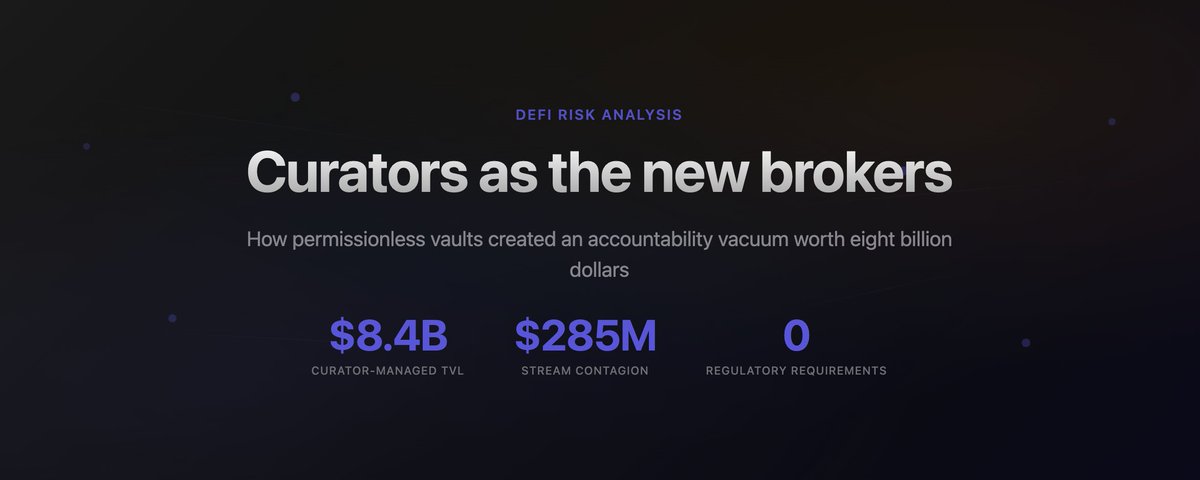

Stream Finance Collapse in November 2025

The collapse of Stream Finance in November 2025 fully exposed the fatal flaws of this architecture under stress. The incident triggered a chain reaction of losses totaling $285 million across the ecosystem.

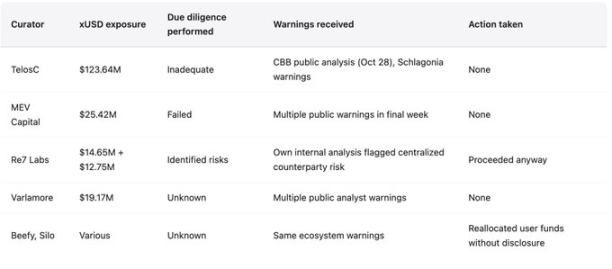

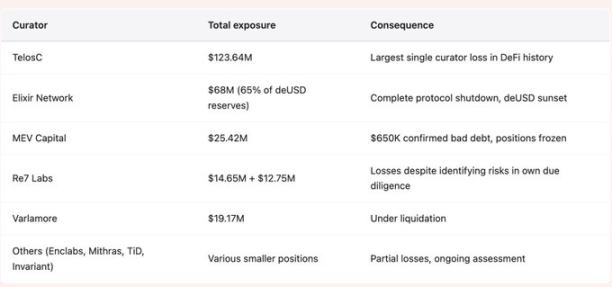

Multiple fund managers, including TelosC ($123.64 million), Elixir ($68 million), MEV Capital ($25.42 million), and Re7 Labs (two vaults totaling $27.4 million), had heavily concentrated user deposits with a single counterparty. That counterparty operated with 7.6x leverage using only $1.9 million in real collateral.

Warning signs were clear and specific. Crypto KOL CBB publicly disclosed its leverage ratio on October 28. Yearn Finance directly warned the Stream team 172 days before the collapse. Yet these warnings were ignored because the existing incentive structure actively encouraged such neglect.

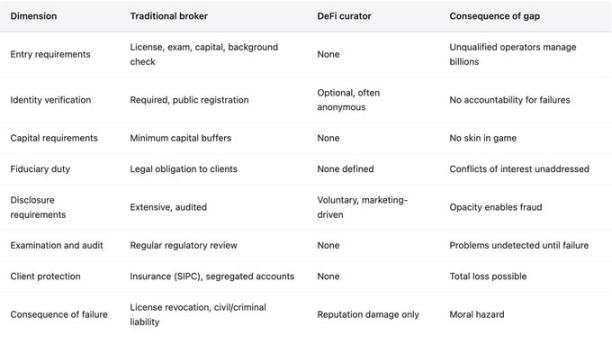

Comparison with Traditional Financial Intermediaries

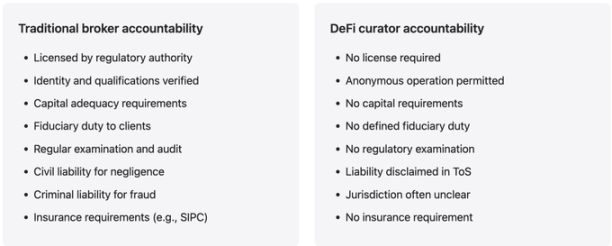

The DeFi fund manager model adopts patterns from traditional finance but discards accountability mechanisms built over centuries of painful lessons.

When traditional banks or brokers manage client funds, they face capital requirements, registration obligations, fiduciary duties, and regulatory scrutiny. In contrast, DeFi fund managers managing client funds are driven solely by market incentives—market incentives that favor asset accumulation and return maximization over risk management.

The protocols supporting these managers claim to be "neutral infrastructure," earning fees from activity while disclaiming responsibility for resulting risks. This position is fundamentally untenable. Traditional finance abandoned this idea decades ago after repeated disasters, having learned through bloodshed that fee-earning intermediaries cannot be fully absolved of liability.

The Double-Edged Sword of Permissionless Architecture

Morpho and Euler operate as permissionless lending infrastructures. Anyone can create vaults, set risk parameters, choose collateral, and begin accepting deposits. Protocols provide smart contract infrastructure and earn fees from usage.

This architecture has advantages:

-

Promotes innovation: Eliminates potential conflicts that might hinder new approaches due to unfamiliarity or competitive relationships.

-

Improves inclusivity: Provides services to participants excluded by traditional systems.

-

Enhances transparency: Creates an auditable record of all transactions on-chain.

But it also brings fundamental problems, clearly exposed during the November 2025 event:

-

No admission review: Cannot guarantee the quality of managers.

-

No registration requirement: No way to hold managers accountable when they fail.

-

No identity disclosure: Managers can accumulate losses under one name and then rebrand and restart.

-

No capital requirements: Managers have no skin in the game beyond reputation, which is easily discarded.

As BGD Labs founder Ernesto Boado put it bluntly: Managers are "freely selling your brand to gamblers." Protocols earn revenue, managers collect fees, and users bear all losses when inevitable failures occur.

Typical Failure Mode: Bad Drives Out Good

Stream Finance perfectly highlights the specific failure mode bred by permissionless architecture. Since anyone can create vaults, managers compete for deposits primarily by offering higher yields. Higher yields either come from genuine alpha (rare and hard to sustain) or from increased risk (common and catastrophic when realized).

Users see "18% annualized yield" and stop questioning, assuming experts called "risk managers" have done proper due diligence. Managers see opportunities for fee income and accept risks that prudent risk management should reject. Protocols see growing total value locked and fee revenue, so choose not to intervene, citing the principle that "permissionless" systems should not impose limits.

This competition creates a vicious cycle: conservative curators offer low yields, attract fewer deposits; aggressive curators offer high yields, attract more deposits, earn massive fees—until disaster strikes. Markets cannot distinguish sustainable returns from unsustainable gambles before failure occurs. When losses happen, all participants share the burden, while managers remain largely unaffected except for reputational damage easily discarded.

Conflict of Interest and Broken Incentives

The manager model contains inherent conflicts of interest, making failures like Stream Finance almost inevitable.

-

Goal misalignment: Users seek safety and reasonable returns; managers pursue fee income.

-

Risk mismatch: This goal divergence becomes most dangerous when profit opportunities require taking risks users would otherwise reject.

The RE7 Labs case is highly instructive. During due diligence prior to integrating xUSD, they correctly identified "centralized counterparty risk" as a concern. Stream concentrated risk through a single position managed by an anonymous external fund manager with completely opaque strategy. RE7 Labs understood the risk but proceeded anyway, citing "strong demand from users and the network." The lure of fee income outweighed concerns about user fund safety. When losses occurred, RE7 Labs suffered only reputational harm, while users bore 100% of the financial loss.

This incentive structure does not merely misalign—it actively penalizes prudence:

-

Managers who reject high-risk, high-yield opportunities lose deposits to competitors who accept them.

-

Prudent managers earn lower fees and appear underperforming.

-

Reckless managers earn high fees, attract more deposits, and keep their gains even after exposure.

Many managers allocated user funds into xUSD positions without adequate disclosure, exposing depositors unknowingly to Stream’s up to 7.6x leverage and off-chain opaque risks.

Asymmetric Fee Structures

Managers typically charge 5%-15% performance fees on profits. This seems reasonable but is highly asymmetric:

-

Profit sharing: Managers participate in upside gains.

-

No downside exposure: Managers bear no corresponding risk during losses.

Example: A vault with $100 million in deposits generating 10% return earns the manager $1 million (at 10% performance fee). If the manager doubles the risk to achieve 20% return, they earn $2 million. If the risk materializes and users lose 50% ($50 million) of principal, the manager only loses future income from that vault—the previously earned fees remain theirs.

Protocol Conflicts of Interest

Protocols themselves face conflicts of interest when dealing with manager failures. Morpho and Euler earn fees from vault activities and thus have an incentive to maximize volume—meaning allowing high-yield (high-risk) vaults that attract deposits. They claim neutrality, arguing permissionless systems shouldn't impose limits. But they are not neutral—they profit from the very activities they enable.

Traditional financial regulation recognized centuries ago that entities profiting from intermediary activities cannot be fully absolved of responsibility for the risks those activities generate. Commission-earning brokers owe duties to their clients—a principle DeFi protocols have yet to accept.

Accountability Vacuum

-

Traditional finance: Losing client funds may trigger regulatory investigations, license revocation, civil liability, or even criminal prosecution. This deters reckless behavior ex ante.

-

DeFi fund managers: Losing client funds results only in reputational damage, often escapable via rebranding. No regulatory jurisdiction, unclear legal standing of fiduciary duty, no civil liability (due to unknown identity +免责 terms in service).

March 2024 Morpho incident: Approximately $33,000 lost due to oracle price deviation. When users sought accountability, the protocol, manager, and oracle provider blamed each other—no one took responsibility or offered compensation. Though small, this established a precedent: "losses occur, no one is held accountable."

This accountability vacuum is by design, not accident. Protocols avoid liability through disclaimers in terms of service, emphasizing "permissionless means no behavioral control," and placing governance under foundations/DAOs in lightly regulated jurisdictions. This benefits protocols legally but creates a moral hazard environment where entities manage billions in user funds without accountability: privatizing gains, socializing losses.

Anonymity and Accountability

Many managers operate anonymously or pseudonymously, justified by security and privacy—but this directly undermines accountability:

-

No ability to pursue legal liability.

-

No mechanism to ban operators based on failure history.

-

No way to enforce professional or reputational sanctions tied to real identities.

In traditional finance, even without regulation, those who destroy client funds still face civil liability and reputational tracking—neither exists for DeFi fund managers.

Black-Box Strategies and Blind Trust in Authority

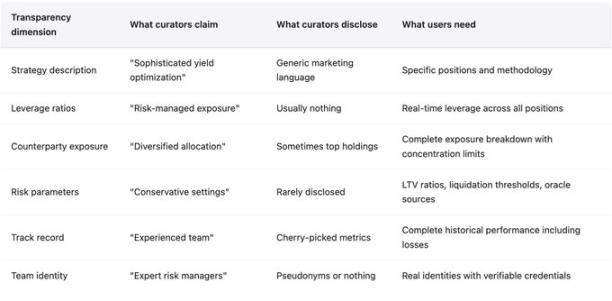

Managers present themselves as risk management experts, but November 2025 revealed many lack necessary infrastructure, expertise, or even willingness.

-

Traditional institutions: 1-5% of staff dedicated to risk management, with independent committees, oversight teams, stress tests, and scenario analysis requirements.

-

DeFi fund managers: Often small teams or individuals focused primarily on yield generation and asset accumulation.

Strategy details are rarely meaningfully disclosed. Terms like "delta-neutral trading" or "hedged market making" sound sophisticated but reveal nothing about actual positions, leverage, counterparty risks, or risk parameters. Opacity justified as "protecting strategy" actually breeds fraud and recklessness until collapse.

Stream Finance reached catastrophic levels of opacity: claiming $500 million in total value locked, only $200 million was verifiable on-chain. The remaining $300 million resided with an "external fund manager" whose identity, credentials, strategy, and risk controls were entirely undisclosed. Actual positions and leverage behind the jargon remained unknown. Post-mortem analysis revealed synthetic expansion of 7.6x via recursive borrowing backed by only $1.9 million in real collateral—depositors were completely unaware their "stablecoin" was supported by infinitely recursive borrowed assets rather than real reserves.

The danger of blind trust in authority lies in users abandoning independent judgment. The RE7 Labs case shows that even when due diligence identifies risks, commercial incentives override correct conclusions. This is worse than incompetence—it's the ability to identify risk but choosing to ignore it due to incentives.

Proof of Reserves: Technically Mature, Rarely Implemented

Verifiable proof-of-reserves cryptography (e.g., Merkle trees, zero-knowledge proofs) has been mature for decades—efficient and privacy-preserving. Stream Finance’s failure to implement any proof-of-reserves wasn’t due to technical limitations but a deliberate choice of opacity, allowing fraud to persist for months despite multiple public warnings. Protocols should require managers handling large deposits to provide proof of reserves. Lack of proof should be treated like a bank refusing external audit.

Evidence from the November 2025 Event

The Stream Finance collapse is a complete case study of manager model failure, embodying all issues: inadequate due diligence, conflict of interest, ignored warnings, opacity, and lack of accountability.

Failure Timeline

-

172 days before collapse: Schlagonia analyzed and directly warned that Stream’s structure was doomed. A five-minute analysis uncovered fatal flaws: $170 million in on-chain collateral backing $530 million in loans (4.1x leverage), strategy involving recursive borrowing creating circular dependencies, and another $330 million in total value locked completely off-chain and opaque.

-

October 28, 2025: CBB issued a public, specific warning listing leverage and liquidity risks, calling it "degenerate gambling." Other analysts followed.

-

Warnings ignored: Managers such as TelosC, MEV Capital, and Re7 Labs maintained large exposures and continued attracting deposits. Acting on warnings would mean reducing positions and fee income, making them appear underperforming in competition.

-

November 4, 2025: Stream announced its external fund manager lost ~$93 million. Withdrawals paused, xUSD dropped 77%, Elixir’s deUSD (65% of reserves lent to Stream) plunged 98%. Total contagion risk reached $285 million, Euler’s bad debt ~$137 million, over $160 million in funds frozen.

DeFi Fund Managers vs. Traditional Brokers

This comparison aims to highlight missing accountability mechanisms in the manager model—not to claim traditional finance is perfect or its regulations should be copied wholesale. Traditional finance has flaws, but the accountability mechanisms developed through costly lessons have been explicitly discarded by the curator model.

Technical Recommendations

The manager model does have benefits: improving capital efficiency through expert parameter setting; enabling experimentation and innovation; lowering barriers and increasing inclusivity. These benefits can be preserved while addressing accountability issues. Recommendations based on five years of DeFi failure experience:

-

Mandatory identity disclosure: Managers handling large deposits (e.g., over $10 million) must disclose real identities to the protocol or an independent registry. Not requiring full public detail, but ensuring traceability for fraud or gross negligence. Anonymous operation is incompatible with managing large-scale user funds.

-

Capital requirements: Managers must hold risk capital that is at risk if vault losses exceed thresholds (e.g., 5% of deposits). This aligns their interests with users—for example, by posting collateral or holding junior tranches in proprietary vaults absorbing first losses. Current structures with no skin in the game create moral hazard.

-

Mandatory disclosure: Managers must disclose strategies, leverage, counterparty risks, and risk parameters in standardized formats. "Protecting proprietary strategy" is often an excuse—most strategies are known yield farming variants. Real-time disclosure of leverage and concentration doesn’t harm alpha but helps users understand risk.

-

Proof of reserves: Protocols should require curators managing large deposits to provide proof of reserves. Mature cryptographic techniques can verify solvency and reserve ratios without revealing strategies. Managers without proof should be disqualified. This would have prevented Stream from operating with $300 million in unverifiable off-chain positions.

-

Concentration limits: Protocols should enforce concentration caps at the smart contract level (e.g., max 10–20% exposure to a single counterparty) to prevent excessive concentration. Elixir lending 65% of its reserves to Stream and suffering inevitable fallout serves as a lesson.

-

Protocol accountability: Protocols earning fees from manager activities should bear partial responsibility. For example, allocating part of protocol fees to an insurance fund compensating user losses, or maintaining whitelists excluding managers with poor track records or insufficient disclosure. The current model—earning fees while bearing zero liability—is economically unreasonable.

Conclusion

The currently implemented manager model is an accountability vacuum, where billions in user funds are managed by entities facing no real constraints on behavior and no real consequences for failure. This is not to reject the model itself—capital efficiency and professional risk management do have value. Rather, it emphasizes that the model needs to incorporate the accountability mechanisms that traditional finance developed through painful experience.

DeFi can develop mechanisms suited to its nature, but it cannot simply discard accountability and expect better outcomes than pre-accountability traditional finance. The current structure ensures failures will repeat. Failures will continue until the industry accepts: fee-earning intermediaries cannot be fully absolved of responsibility for the risks they create.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News