Financial Black Hole: Stablecoins Are Devouring Banks

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Financial Black Hole: Stablecoins Are Devouring Banks

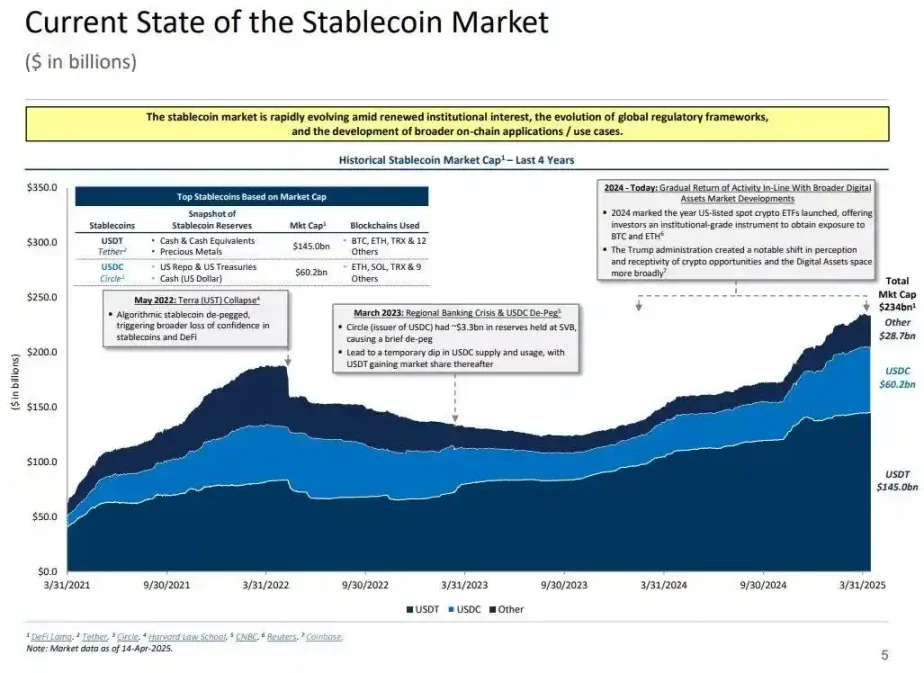

Stablecoins are consuming liquidity in the guise of "narrow banking," quietly reshaping the global financial architecture.

Author: @0x_Arcana

Translation: Peggy, BlockBeats

Stablecoins Resurrect "Narrow Banking"

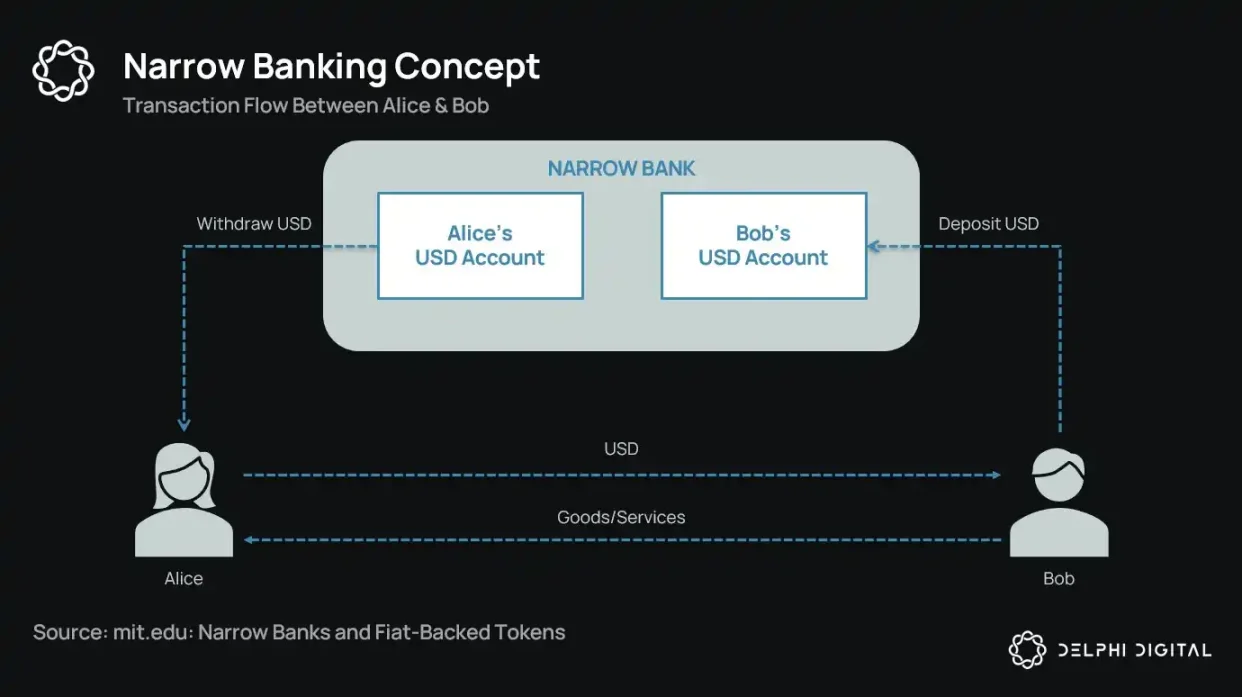

For over a century, monetary reformers have repeatedly proposed variations of "narrow banking"—financial institutions that issue money but do not provide credit. From the 1930s Chicago Plan to modern proposals like The Narrow Bank (TNB), the core idea is to prevent bank runs and systemic risk by requiring money-issuing entities to hold only safe, liquid assets such as government bonds.

Yet regulators have consistently rejected the implementation of narrow banking.

Why? Because despite their theoretical safety, narrow banks disrupt the core mechanism of the modern banking system—credit creation. They drain deposits from commercial banks, hoard risk-free collateral, and break the link between short-term liabilities and productive lending.

Ironically, the crypto industry has now resurrected the narrow banking model through fiat-backed stablecoins. Stablecoins behave almost identically to narrow bank liabilities: they are fully collateralized, instantly redeemable, and primarily backed by U.S. Treasuries.

After waves of bank failures during the Great Depression, economists from the Chicago School proposed separating money creation from credit risk entirely. Under the 1933 "Chicago Plan," banks would be required to hold 100% reserves against demand deposits, with loans funded only by time deposits or equity—not by deposits used for payments.

The goal was to eliminate bank runs and reduce financial instability. If banks cannot lend out deposits, they won't collapse due to liquidity mismatches.

In recent years, this idea has resurfaced as "narrow banking." Narrow banks accept deposits but invest only in safe, short-term government securities such as Treasury bills or reserves at the Federal Reserve. A recent example is The Narrow Bank (TNB), which applied in 2018 to access interest on excess reserves (IOER) at the Fed—but was denied. The Fed feared TNB would become a risk-free, high-yield deposit alternative that could "undermine the transmission mechanism of monetary policy."

What regulators truly fear is that if narrow banks succeed, they could weaken the commercial banking system by siphoning deposits away from traditional banks and stockpiling safe collateral. In essence, narrow banks create money-like instruments without supporting credit intermediation.

My personal "conspiracy theory" view: the modern banking system is essentially a leveraged illusion, operating under the assumption that no one will try to exit en masse. Narrow banking directly threatens this model. But upon reflection, it's not really a conspiracy—it simply exposes the fragility of the existing system.

Central banks don’t print money directly; instead, they indirectly control it through commercial banks—encouraging or restricting lending, providing support during crises, and maintaining sovereign debt liquidity by injecting reserves. In exchange, commercial banks gain zero-cost liquidity, regulatory leniency, and an implicit promise of bailouts during emergencies. Within this structure, traditional commercial banks aren’t neutral market participants—they are tools of state economic intervention.

Now imagine a bank saying: “We don’t want leverage—we just want to offer users safe money backed 1:1 by Treasuries or Fed reserves.” This would make the current fractional-reserve banking model obsolete and directly threaten the entire system.

The Fed’s rejection of TNB’s master account application exemplifies this threat. The concern isn’t that TNB might fail, but that it might actually succeed. If people can access a currency that is always liquid, free of credit risk, and earns interest, why would they keep money in traditional banks?

This is precisely where stablecoins come in.

Fiat-backed stablecoins replicate the narrow banking model almost exactly: issuing digital liabilities redeemable for dollars, backed 1:1 by safe, liquid off-chain reserves. Like narrow banks, stablecoin issuers do not use reserve funds for lending. While issuers like Tether currently don’t pay interest to users, that’s beyond the scope of this article. This piece focuses on the role of stablecoins within modern monetary architecture.

Assets are risk-free, liabilities are instantly redeemable and function as par-value money; there is no credit creation, no maturity mismatch, and no leverage.

While narrow banks were strangled at birth by regulators, stablecoins face no such constraints. Many stablecoin issuers operate outside the traditional banking system, and demand continues to grow—especially in high-inflation countries and emerging markets where access to dollar banking services is limited.

From this perspective, stablecoins have evolved into a "digitally native Eurodollar," circulating beyond the U.S. banking system.

But this raises a critical question: what happens to systemic liquidity when stablecoins absorb a significant portion of U.S. Treasuries?

The Liquidity Blackhole Thesis

As stablecoins grow in scale, they increasingly resemble global liquidity "islands": drawing in dollar inflows while locking up safe collateral within a closed loop that cannot re-enter traditional financial circuits.

This could lead to a "liquidity blackhole" in the U.S. Treasury market—where large volumes of Treasuries are absorbed by the stablecoin system but cannot circulate in traditional interbank markets, thereby affecting overall liquidity supply across the financial system.

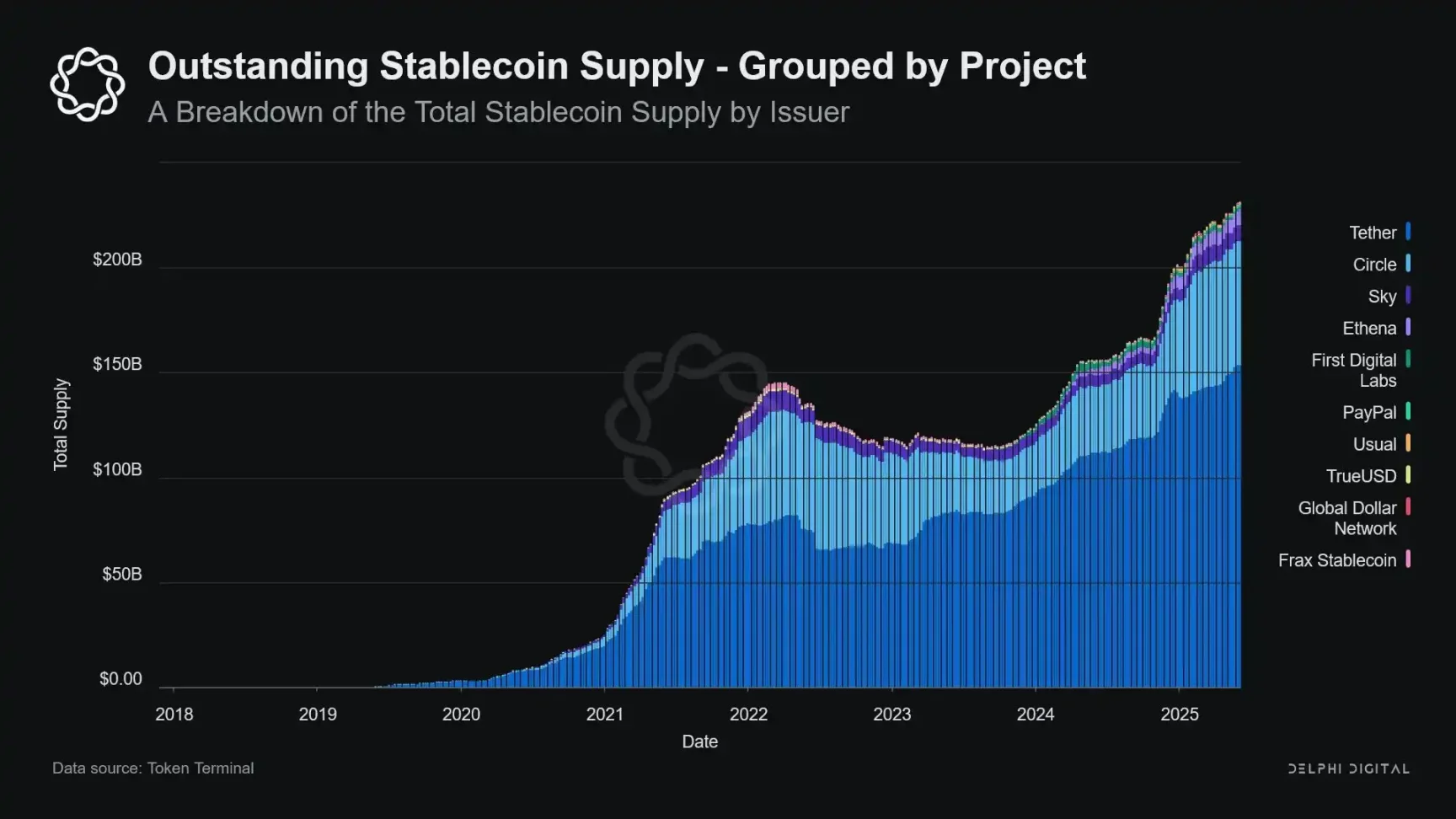

Stablecoin issuers are persistent net buyers of short-term U.S. Treasuries. For every dollar of stablecoin issued, an equivalent asset—typically Treasury bills or reverse repo positions—must appear on the balance sheet. Unlike traditional banks, however, stablecoin issuers do not sell these Treasuries to fund loans or shift into riskier assets.

As long as stablecoins remain in circulation, their reserves must be held indefinitely. Redemptions occur only when users exit the stablecoin ecosystem, which is rare—since on-chain users typically just swap between tokens or use stablecoins as long-term cash equivalents.

This turns stablecoin issuers into one-way liquidity "blackholes": they absorb Treasuries but rarely release them. Once locked in custodial reserve accounts, these Treasuries exit the traditional collateral chain—they cannot be rehypothecated or used in repo markets—and are effectively removed from the monetary circulation system.

This creates a "sterilization effect." Just as the Fed’s quantitative tightening (QT) tightens liquidity by removing high-quality collateral, stablecoins perform a similar function—but without policy coordination or macroeconomic intent.

More troubling is the concept of "shadow quantitative tightening" (Shadow QT) and its potential for self-reinforcing feedback loops. It is acyclical, unaffected by macroeconomic conditions, and expands solely with growing stablecoin demand. Moreover, because many stablecoin reserves are held offshore in jurisdictions with lower transparency, regulatory visibility and coordination become significantly harder.

Worse still, this mechanism may become procyclical under certain conditions. During periods of heightened market risk aversion, demand for on-chain dollars often rises, driving increased stablecoin issuance and pulling even more U.S. Treasuries out of circulation—precisely when the market needs liquidity most, amplifying the blackhole effect.

Although stablecoins are still much smaller than the Fed’s QT in scale, their mechanisms are strikingly similar, producing comparable macro effects: fewer Treasuries in circulation, tighter liquidity, and marginal upward pressure on interest rates.

And rather than slowing down, this growth trend has accelerated significantly over the past few years.

Policy Tensions and Systemic Risk

Stablecoins occupy a unique intersection: they are neither banks, nor money market funds, nor traditional payment service providers. This identity ambiguity creates structural tension for policymakers: too small to be deemed a systemic risk and regulated accordingly; too important to be outright banned; too useful, yet too dangerous, to be allowed to grow unregulated.

A key function of traditional banks is transmitting monetary policy into the real economy. When the Fed raises rates, bank lending tightens, deposit rates adjust, and credit conditions shift. But since stablecoin issuers do not lend, they cannot transmit interest rate changes into broader credit markets. Instead, they absorb high-yielding U.S. Treasuries without offering credit or investment products—and many stablecoins don’t even pay interest to holders.

The reason the Fed rejected The Narrow Bank’s (TNB) application for a master account wasn’t due to credit risk concerns, but fear of financial disintermediation. The Fed worried that if a risk-free bank offered interest-bearing accounts backed by reserves, it would draw massive flows out of commercial banks, potentially destabilizing the banking system, squeezing credit availability, and concentrating monetary power within a "liquidity-sterilizing vault."

The systemic risks posed by stablecoins are similar—but this time, they don’t even need the Fed’s approval to operate.

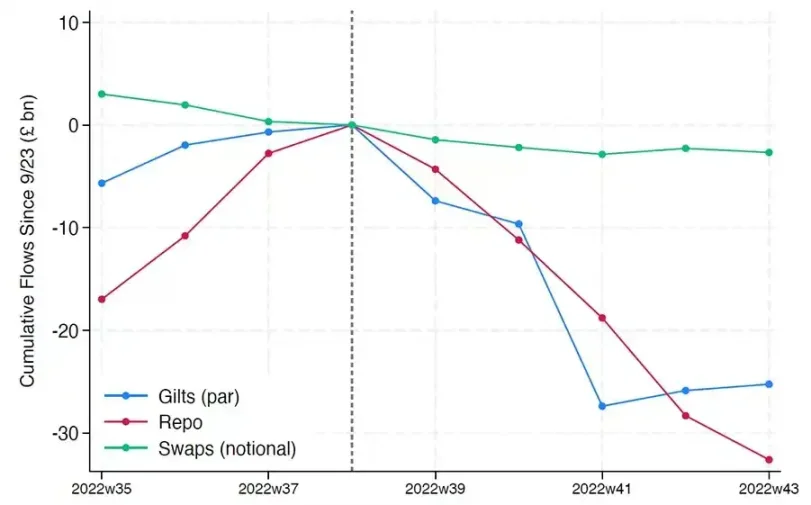

Beyond disintermediation, other risks remain. Even without offering yield, stablecoins face "run risk": if market confidence in reserve quality or regulatory stance erodes, mass redemptions could ensue. In such cases, issuers might be forced to dump Treasuries under market stress—similar to the 2008 money market fund crisis or the UK’s LDI crisis in 2022.

Unlike banks, stablecoin issuers have no "lender of last resort." Their shadow banking nature allows them to rapidly grow into systemic roles—but also to unravel just as quickly.

Then again, like Bitcoin, there’s also a small fraction of "lost seed phrases." In the context of stablecoins, this means some funds will remain permanently locked in U.S. Treasuries, unredeemable, effectively becoming permanent liquidity blackholes.

Originally a niche financial product within crypto trading venues, stablecoin issuance has now become a primary channel for dollar liquidity—flowing through exchanges, DeFi protocols, and extending into cross-border remittances and global commercial payments. Stablecoins are no longer peripheral infrastructure; they are gradually becoming the foundational layer for dollar transactions outside the banking system.

Their growth is "sterilizing" collateral, locking safe assets into cold storage. This represents a form of balance sheet contraction occurring outside central bank control—an "ambient quantitative tightening" (ambient QT).

And while policymakers and the traditional banking system struggle to maintain the old order, stablecoins are quietly reshaping it.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News