When a father uses prediction markets to alleviate parenting anxiety

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

When a father uses prediction markets to alleviate parenting anxiety

Predictive market thinking ultimately offers not certainty, but clarity.

Author: Polyfactual

Translation: TechFlow

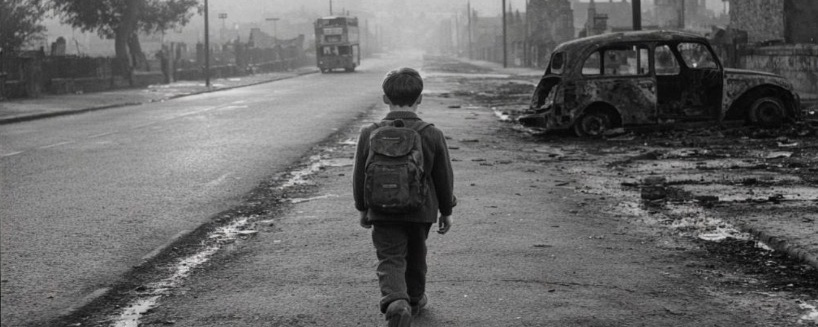

On Tuesday morning last week, I stood frozen in the pickup line at my son's elementary school, hand on his backpack. Another school shooting had dominated the news headlines over the weekend.

As he ran excitedly into the school building, I felt that familiar tightness in my chest—a heart-wrenching sensation that anything could happen as they grow more independent in this hostile world.

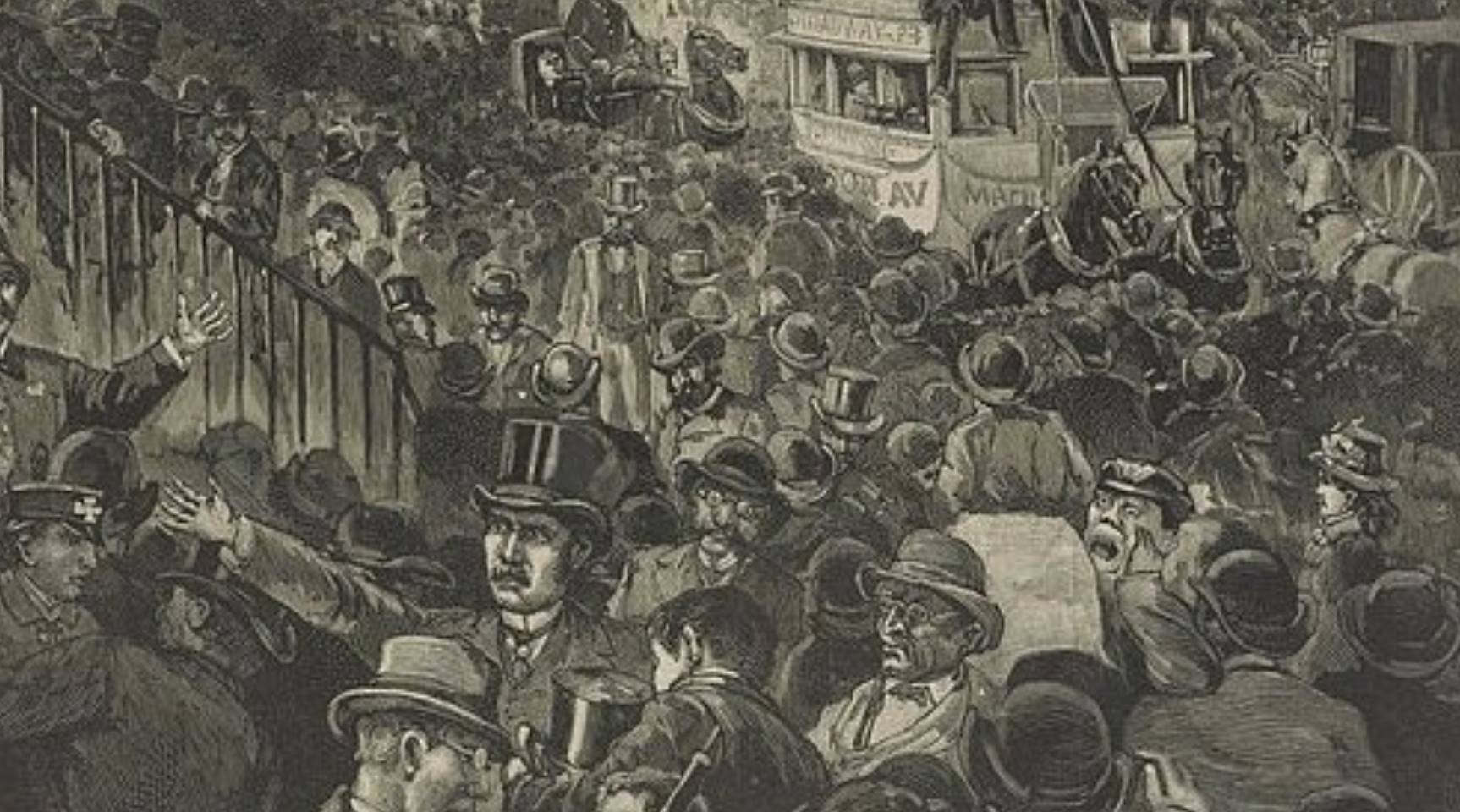

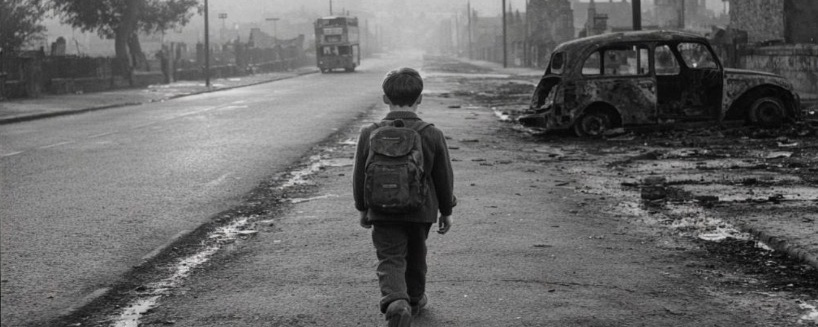

Driving to work, I played a long audiobook I’d been listening to: *Say Nothing*, a historical account of The Troubles in Northern Ireland—the three-decade-long period of anti-colonial violence from 1969 to the late 1990s, during which 1,860 children were killed.

At certain times, Northern Ireland was a genuine war zone, with streets filled with bombings, shootings, and military presence. The book details the horrific fates of innocent victims, most chillingly children who were accidentally harmed or killed. Yet when you actually crunch the numbers, you find that during the entire terrifying period, a child’s annual risk of being killed was about 1.2 per 100,000 children.

Participating in prediction markets has activated the analytical part of my brain, helping me process problems that once seemed unresolvable. I calculated the data on U.S. school shootings.

Currently, the annual risk of a K–12 student dying in a school shooting is about 0.06 per 100,000 students. My son—a public school student in 2025—faces a statistically lower risk than a child attending school in Belfast in 1975. In other words, during The Troubles in Northern Ireland, a child was about 20 times more likely to be violently killed than an American student today is to die in a school shooting.

This realization doesn’t make school shootings any less tragic. Each shooting is an absolute disaster, a failure of society to protect children. But it has an unexpected effect: it allows me to let my son live freely.

The Anxiety Trap

Here’s something no one tells you about parenting in the information age: your brain is fundamentally bad at assessing risk. Our brains are wired to respond to vivid, emotional threats—the kind accompanied by breaking news alerts and endless Twitter/X updates about tragic events. But we’re terrible at properly weighing these threats against base probabilities and statistical likelihoods.

This is where prediction market thinking comes in.

Prediction markets work by aggregating information from multiple sources and forcing people to put real stakes behind their beliefs. They excel at cutting through noise because they penalize emotional reasoning and reward accuracy.

You can’t sustain a position in a prediction market based solely on how you feel—you must think in terms of actual probabilities, detached from emotion. I’m not suggesting we all become cold, calculating machines indifferent to our children’s safety.

I am suggesting that adopting a probabilistic thinking framework—one rooted in the mental models that make prediction markets effective—can be a genuinely life-improving tool.

Deconstructing Probability

After dropping my child off that morning, I began applying this mindset to other anxieties—not to dismiss them, but to resize them appropriately.

I drive more frequently than average, so I looked up the data: the annual risk of an American dying in a car crash is about 12 per 100,000. That’s indeed a major cause of death, and the risk is clearly substantial. But something I hadn’t considered before: when I adjusted for being a focused driver who doesn’t livestream on TikTok while driving, my personal risk dropped significantly.

There were more factors: I don’t drink and drive, I always wear my seatbelt rigorously, I never text while driving, and my car has modern safety features unavailable to my parents’ generation. Each factor further reduces the risk.

By running the numbers, I realized that while driving does carry risk, my specific risk profile is far lower than what the news implies. More importantly, it helped clarify what truly matters: the behavioral factors I can control. I can’t eliminate risk entirely, but I can be deliberate.

Prediction market thinking poses a key question: among all available information, what should I actually pay attention to?

Decision-Making Under Uncertainty

This mindset is especially powerful for major life decisions. Should we move for a job opportunity? Should our child skip a grade? Should I try experimental ketamine therapy?

Traditional advice is to list pros and cons or “follow your gut.” But prediction market thinking offers a more structured approach: estimate the probabilities of different outcomes, assign rough values to them, then see what the expected value calculation suggests.

When my wife considered switching to a lower-paying but potentially more fulfilling job, we were stuck.

Then we started breaking it down:

⇨ What’s the probability she’ll be happier? (We estimated 70%)

⇨ How much happier would she be? Measured on a rough quantifiable scale.

⇨ What’s the probability financial stress will cause serious issues? (We estimated 20%) • How severe would those issues be?

Just going through this analysis—even before reaching a conclusion—immediately clarified our thinking. We realized we were over-weighting financial risk because it felt concrete, while under-valuing fulfillment because it felt vague.

Prediction market thinking forced us to make our assumptions explicit. We made the change—sometimes difficult, but the right choice.

Limits of the Framework

I need to be clear: this isn’t about reducing life to a spreadsheet. Many of our struggles stem from threats we exaggerate or opportunities we overlook due to miscalibrated risk perception.

Probabilistic thinking doesn’t mean detachment or cold calculation—it means honesty about what we actually know versus what we fear. It means distinguishing between “this feels scary” and “this is actually dangerous.”

Everyday Prediction Markets

Here’s how it works in practice:

Before making a decision: Don’t ask “What should I do?” Ask “What are the possible outcomes? What’s the probability of each?” Write them down with rough percentages. You might discover where your thinking lacks clarity.

When feeling anxious: Ask yourself what evidence would change your assessment. If no evidence could change it (e.g., you’d worry equally whether the risk was 0.001% or 10%), then you’re not dealing with calibrated concern, but generalized anxiety that needs a different approach.

For recurring worries: Track them. I started logging every specific scenario I worried about regarding my child. A week later, none of the vivid scenarios I feared had occurred—but things I hadn’t worried about did happen (like injuries on the playground or an unexpected new behavioral issue). This didn’t stop me from worrying completely, but it did help me see the world more objectively.

During conflicts with a partner: Instead of arguing that something is “too risky” or “perfectly safe,” assign numbers. For example: What are the outcomes of clinical ketamine therapy? How many people in study groups had bad experiences, and how many experienced full psychological rebirth and relief from mental health issues? Gather data, then decide.

Living in the Distribution

The deepest insight from this mindset isn’t about any single decision, but accepting that we live in a probabilistic universe. As James Clerk Maxwell said: “The true logic of this world is the calculus of probabilities.”

Bad things happen. Good things happen. Most things fall somewhere in between. You can’t optimize your way to zero risk, and trying to do so may cause you to miss the full texture of life.

Thinking about parents during The Troubles in Northern Ireland, sending their children to school every day amid real violence, I don’t see negligence. They made a rational choice: life must go on, and the alternative—locking their children away at home out of fear—is a different kind of tragedy.

Prediction market thinking ultimately offers not certainty, but clarity. Not fearlessness, but targeted concern. Not risk elimination, but wise discernment about which dangers should change our behavior and which shouldn’t.

I still feel worry when I drop my son off at school—and probably always will. But now, when my chest tightens, I can pause and ask myself: Is this fear proportionate to the actual risk, or is my brain doing what it usually does—catastrophizing, scanning for threats, trying to protect what I love most?

It’s usually the latter. And I’m slowly learning to let him walk easily through the school doors—and to let my own mind follow.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News