Stablecoins will replace credit cards as the mainstream payment method in the United States

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Stablecoins will replace credit cards as the mainstream payment method in the United States

Stablecoins will follow the development path of credit cards, then replace them.

By: Daniel Barabander

Translated by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

There is currently intense discussion about stablecoins in the context of U.S. consumer payments. But most people view stablecoins as a "sustaining technology" rather than a "disruptive technology." They believe that while financial institutions may use stablecoins for more efficient settlements, the value proposition for most American consumers isn't strong enough to pull them away from dominant, high-stickiness payment methods like credit cards.

This article argues how stablecoins can become a mainstream payment method in the U.S., not just a settlement tool.

How Credit Cards Built Payment Networks

First, we must acknowledge that getting people to adopt a new payment method is extremely difficult. A new payment method only becomes valuable when enough people in the network use it, yet people only join when the network already holds value. Credit cards overcame this "cold start" problem through a two-step process and became the most widely used consumer payment method in the U.S. (accounting for 37%), surpassing previously dominant cash, checks, and early merchant-specific or industry-specific charge cards.

Step One: Leveraging Intrinsic Advantages That Don’t Require a Network

Credit cards initially expanded their market by solving pain points for a small segment of consumers and merchants across three dimensions: convenience, incentives, and sales growth. Take BankAmericard—the first mass-market bank credit card launched by Bank of America in 1958 (which later evolved into today’s Visa network)—as an example:

-

Convenience: BankAmericard allowed consumers to pay once at the end of the month instead of carrying cash or writing checks at checkout. While merchants previously offered similar deferred-payment charge cards, those were limited to individual stores or specific categories (like travel and entertainment). BankAmericard, however, could be used at any participating merchant, covering nearly all consumer needs.

-

Incentives: Bank of America drove adoption by mailing 65,000 unsolicited BankAmericard credit cards to residents of Fresno, each with a pre-approved flexible line of credit—an unprecedented move at the time. Cash and checks couldn’t offer such incentives, and while early charge cards provided short-term credit, they were typically restricted to high-income or existing customers and limited to certain merchants. BankAmericard’s broad credit access particularly appealed to lower-income consumers who had previously been excluded.

-

Sales Growth: BankAmericard helped merchants increase sales through credit-based spending. Cash and checks did not expand consumers’ purchasing power, and while early charge cards boosted sales, they required merchants to manage their own credit systems, customer onboarding, collections, and risk controls—operations too costly for all but large merchants or associations. BankAmericard gave small businesses access to credit-driven sales growth.

BankAmericard succeeded in Fresno and gradually expanded to other cities in California. However, due to regulations limiting Bank of America to operations within California, it quickly realized that “for a credit card to be truly useful, it must be accepted nationwide.” It then licensed the BankAmericard intellectual property to banks outside California for a $25,000 franchise fee plus transaction royalties. Each licensed bank used this IP to build its own local consumer and merchant networks.

Step Two: Expansion and Interconnection of Credit Card Payment Networks

At this stage, BankAmericard had evolved into a series of fragmented “territories,” where consumers and merchants used the card based on its intrinsic advantages. While each territory functioned well internally, the system as a whole couldn’t scale.

Operationally, interoperability between banks was a major issue: authorizing cross-bank transactions using BankAmericard IP required merchants to contact their acquiring bank, which then contacted the issuing bank to confirm authorization, leaving customers waiting in-store. This process could take up to 20 minutes, leading to fraud risks and poor customer experience. Clearing and settlement were equally complex: although acquiring banks received funds from issuers, they lacked incentives to promptly share transaction details so issuers could bill cardholders. Organizationally, the program was run by Bank of America—a competitor to the licensed banks—creating “fundamental distrust” among banks.

To solve these issues, the BankAmericard program spun off in 1970 into a non-stock, nonprofit membership association called National BankAmericard Inc. (NBI), later renamed Visa. Ownership and control shifted from Bank of America to the participating banks. Beyond governance changes, NBI established standardized rules, procedures, and dispute resolution mechanisms. Operationally, it built BASE (BankAmericard Authorization System Exchange), enabling a merchant’s bank to route authorization requests directly to the issuer’s system. Cross-bank authorization dropped to under one minute and supported 24/7 transactions, making it “competitive with cash and check payments” and removing a key adoption barrier. BASE later streamlined clearing and settlement by replacing paper processes with electronic records and shifting bilateral bank settlements to centralized netting via the BASE network. Processes that once took a week could now complete overnight.

By connecting these fragmented payment networks, credit cards overcame the “cold start” problem through supply-demand aggregation. At this point, mainstream consumers and merchants joined because the network itself enabled access to additional users. For consumers, the network created a flywheel of convenience—each new merchant increased the card’s utility. For merchants, it brought incremental sales. Over time, the network leveraged interchange fees generated by interoperability to offer further incentives, accelerating adoption.

The Intrinsic Advantages of Stablecoins

Stablecoins can become mainstream by following the same strategy credit cards used to replace cash, checks, and early charge cards. Let’s analyze stablecoins’ intrinsic advantages across convenience, incentives, and sales growth.

Convenience

Currently, stablecoins aren’t convenient enough for most consumers, who must first convert fiat to cryptocurrency. User experience still needs significant improvement—for instance, even after providing sensitive information to your bank, you often have to repeat the process. You also need another token (like ETH for gas) to cover on-chain transaction fees and ensure the stablecoin matches the merchant’s blockchain (e.g., USDC on Base vs. USDC on Solana are different). From a consumer convenience standpoint, this is entirely unacceptable.

Nevertheless, I believe these issues will be resolved soon. During the Biden administration, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) banned banks from holding crypto (including stablecoins), but that rule was overturned months ago. This means banks will soon be able to custody stablecoins, vertically integrating fiat and crypto and fundamentally solving many current UX issues. Additionally, key technological advances like account abstraction, gas subsidies, and zero-knowledge proofs are improving user experience.

Merchant Incentives

Stablecoins offer merchants entirely new incentive models, especially through permissioned stablecoins.

Note: Permissioned stablecoins are issued not just by merchants but by a broader set of entities—such as fintech companies, exchanges, credit card networks, banks, and payment providers. This article focuses only on merchants.

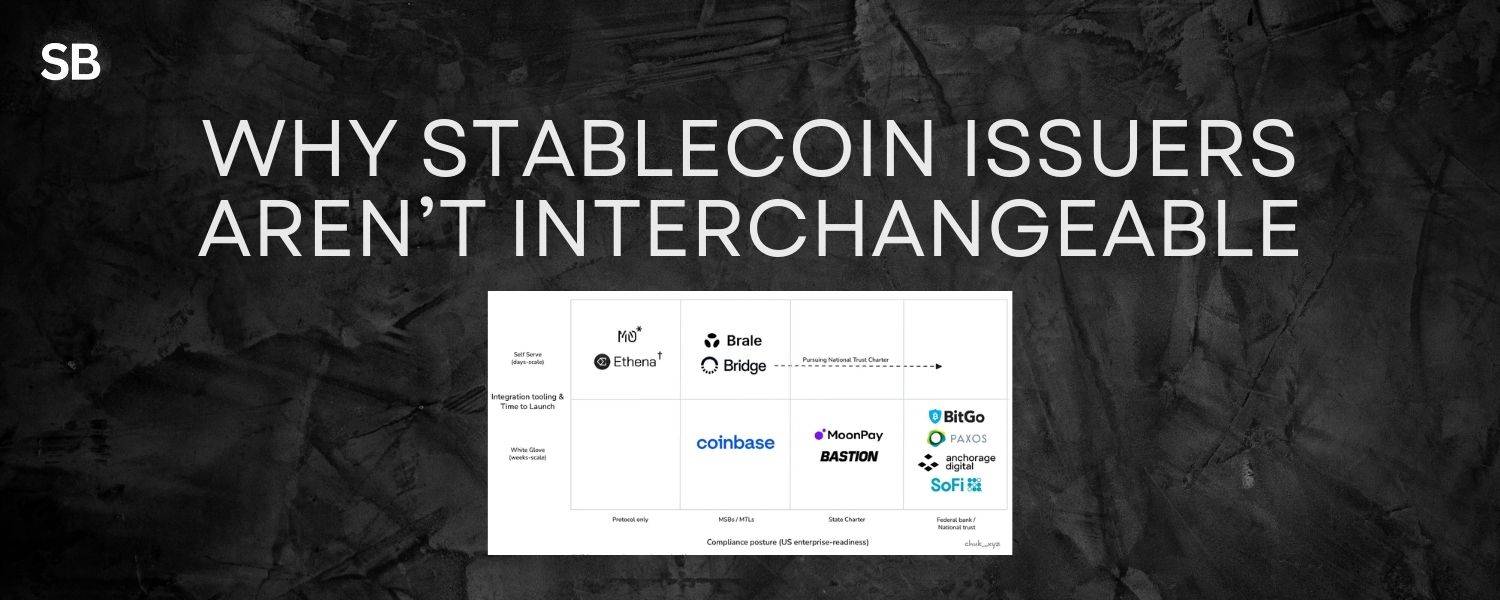

Regulated financial or infrastructure providers (e.g., Paxos, Bridge, M^0, BitGo, Agora, Brale) issue permissioned stablecoins, while another entity brands and distributes them. Brand partners (e.g., merchants) can earn yield from the float generated by these stablecoins.

Permissioned stablecoins resemble Starbucks Rewards programs. Both invest float in short-term instruments and retain the earned interest. Like Starbucks Rewards, permissioned stablecoins can be structured to offer customers points and rewards redeemable only within the merchant’s ecosystem.

Although structurally similar to prepaid loyalty programs, key differences make permissioned stablecoins more feasible for merchants than traditional prepaid programs.

First, as issuing permissioned stablecoins becomes commoditized, launching such programs will approach zero difficulty. The GENIUS Act provides a framework for stablecoin issuance in the U.S. and creates a new class of issuers (non-bank permitted payment stablecoin issuers) with lighter compliance burdens than banks. As a result, an ecosystem of supporting services will emerge. Providers will abstract away UX, consumer protection, and compliance functions. Merchants will launch branded digital dollars at minimal marginal cost. For influential merchants capable of temporarily “locking up” value, the question becomes: why not launch your own rewards program?

Second, unlike traditional rewards, these stablecoins can be used beyond the issuing merchant’s ecosystem. Consumers are more willing to lock up value knowing they can convert it back to fiat, transfer it to others, or eventually spend it at other merchants. While merchants could opt for custom non-transferable stablecoins, I believe they’ll realize transferability significantly increases adoption; permanently locking up value would inconvenience consumers and reduce uptake.

Consumer Incentives

Stablecoins offer a fundamentally different consumer reward model compared to credit cards. Merchants can indirectly use yield earned from permissioned stablecoins to provide targeted incentives—such as instant discounts, shipping credits, early access, or VIP queues. Although the GENIUS Act prohibits sharing yield solely for holding stablecoins, I expect such loyalty rewards to be acceptable.

Due to their programmability—unmatched by credit cards—stablecoins can natively access on-chain yield opportunities (specifically, fiat-backed stablecoins entering DeFi, not hedge funds disguised as stablecoins). Apps like Legend and YieldClub will encourage users to route their float into lending protocols like Morpho to earn yield. I see this as the key breakthrough in stablecoin rewards. Yield attracts users to convert fiat into stablecoins to participate in DeFi, and if spending within this experience is seamless, many will choose to transact directly with stablecoins.

If there’s one thing crypto excels at, it’s airdrops: incentivizing participation through instant, global value transfer. Stablecoin issuers can adopt similar strategies—airdropping free stablecoins (or other tokens)—to attract new users into crypto and encourage stablecoin spending.

Sales Growth

Like cash, stablecoins are bearer assets and don’t inherently stimulate spending like credit cards. However, just as credit card companies built credit on top of bank deposits, it’s easy to imagine providers building similar plans atop stablecoins. Moreover, an increasing number of companies are rethinking credit models, believing DeFi incentives can drive a new primitive for sales growth: “buy now, pay never.” In this model, spent stablecoins are held in custody, generate yield in DeFi, and part of that yield covers the purchase by month-end. Theoretically, this encourages consumers to spend more—something merchants would want to leverage.

Building the Stablecoin Network

We can summarize stablecoins’ intrinsic advantages as follows:

-

Stablecoins are currently neither convenient nor directly conducive to sales growth.

-

Stablecoins can offer meaningful incentives to both merchants and consumers.

The question is: how can stablecoins follow credit cards’ “two-step” strategy to build a new payment method?

Step One: Leverage Intrinsic Advantages That Don’t Require a Network

Stablecoins can focus on niche scenarios where:

(1) Stablecoins are more convenient for consumers than existing payment methods, driving sales growth;

(2) Merchants have incentives to offer stablecoins to consumers willing to sacrifice convenience for rewards.

Niche One: Relative Convenience and Sales Growth

While stablecoins aren’t convenient for most people today, they may be superior for consumers underserved by existing payment methods. These consumers are willing to overcome entry barriers, and merchants will accept stablecoins to reach previously unreachable customers.

A classic example is transactions between U.S. merchants and non-U.S. consumers. Consumers in certain regions—especially Latin America—face extreme difficulty or high costs accessing U.S. dollars to buy goods and services from U.S. merchants. In Mexico, only those living within 20 km of the U.S. border can open dollar accounts; in Colombia and Brazil, dollar banking is fully prohibited; in Argentina, dollar accounts exist but are tightly controlled, quota-limited, and usually offered at official exchange rates far below market rates. This means U.S. merchants lose these sales opportunities.

Stablecoins provide non-U.S. consumers unprecedented access to dollars, enabling them to purchase these goods and services. For these users, stablecoins are relatively convenient because they often lack reasonable alternatives for dollar-denominated consumption. For merchants, stablecoins represent a new sales channel, reaching consumers previously inaccessible. Many U.S. merchants (e.g., AI service providers) have significant demand from non-U.S. consumers and will accept stablecoins to acquire them.

Niche Two: Incentive-Driven Adoption

Many industries have customers willing to sacrifice convenience for rewards. My favorite restaurant offers a 3% discount for cash payments, so I go out of my way to withdraw cash despite the hassle.

Merchants will have incentives to launch branded white-label stablecoins as a way to fund loyalty programs, offering consumers discounts and privileges to drive sales growth. Some consumers will tolerate the friction of entering the crypto world and converting value into white-label stablecoins—especially when incentives are strong and the product is something they love or frequently use. The logic is simple: if I love a product, know I’ll use the balance, and get meaningful returns, I’m willing to endure a poor experience—even hold the funds.

Ideal candidates for white-label stablecoins include merchants with at least one of the following traits:

-

Dedicated fan bases. For example, if Taylor Swift required fans to use “TaylorUSD” to buy concert tickets, fans would comply. She could incentivize holding TaylorUSD with priority access to future tickets or merchandise discounts. Other merchants might also accept TaylorUSD for promotions.

-

High-frequency in-platform usage. For example, in 2019, 48% of sellers on secondhand marketplace Poshmark reinvested part of their earnings into platform purchases. If Poshmark sellers began accepting “PoshUSD,” many would retain the stablecoin to use as buyers trading with other sellers.

Step Two: Connecting Stablecoin Payment Networks

Because the above scenarios are niche, stablecoin usage will be temporary and fragmented. Parties in the ecosystem will define their own rules and standards. Additionally, stablecoins will be issued across multiple blockchains, increasing technical complexity for acceptance. Many stablecoins will be white-labeled and accepted by only a limited number of merchants. The result will be a fragmented payment landscape—each network sustainable within its local niche but lacking standardization and interoperability.

They need a completely neutral and open network to connect them. This network would establish rules, compliance and consumer protection standards, and technical interoperability. The open, permissionless nature of stablecoins makes aggregating this fragmented supply and demand possible. To solve coordination, the network must be open and collectively owned by participants—not vertically integrated with other parts of the payment stack. Turning users into owners enables large-scale scalability.

By aggregating these isolated supply-demand relationships, the stablecoin payment network will solve the “cold start” problem for new payment methods. Just as consumers today tolerate one-time friction to sign up for credit cards, the value of joining a stablecoin network will eventually outweigh the inconvenience of entering the stablecoin world. At that point, stablecoins will enter mainstream adoption in U.S. consumer payments.

Conclusion

Stablecoins won’t directly compete with credit cards in the mainstream market and replace them outright. Instead, they’ll infiltrate from the edges. By solving real pain points in niche markets, stablecoins can achieve sustainable adoption based on relative convenience or superior incentives. The critical breakthrough lies in aggregating these fragmented use cases into an open, standardized, participant-owned network—to coordinate supply and demand and enable scalable growth. If achieved, the rise of stablecoins in U.S. consumer payments will be unstoppable.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News