Security Guide for Crypto Users: Start by Understanding How You Might Be Hacked

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Security Guide for Crypto Users: Start by Understanding How You Might Be Hacked

Most crypto attacks still begin by targeting individuals in non-technical ways, which also gives us the opportunity to prevent them.

Written by: Rick Maeda

Translated by: Golem

A fact is that most crypto users are not hacked through complex vulnerabilities, but rather through clicking, signing, or trusting the wrong things. This report will provide a detailed analysis of these everyday security attacks occurring around users.

From phishing toolkits and wallet drainers to malware and fake customer support scams, most attacks in the crypto industry directly target users rather than protocols, making common attacks center on human factors rather than code-level issues.

Therefore, this report outlines cryptocurrency vulnerabilities targeting individual users, covering not only a range of common vulnerabilities but also practical case studies and daily precautions users should be aware of.

Key Insight: You Are the Target

Cryptocurrency is inherently designed for self-custody. Yet this foundational feature and core industry value often makes you—the user—the single point of failure. In many cases of personal cryptocurrency fund loss, the issue isn't a protocol vulnerability, but a single click, a private message, or one signature. An apparently insignificant daily task, a moment of trust or carelessness, can completely alter someone's cryptocurrency experience.

Hence, this report does not focus on smart contract logic flaws, but instead on individual threat models—analyzing how users are exploited in practice and how to respond. The report focuses specifically on individual-level attack vectors: phishing, wallet authorization, social engineering, and malware. It will also briefly touch upon protocol-level risks to provide an overview of potential exploit types across the cryptocurrency landscape.

Breakdown of Vulnerabilities Facing Individuals

Transactions conducted in a permissionless environment are permanent and irreversible, typically without intermediary intervention. Combined with the need for individual users to interact via devices and browsers holding financial assets with anonymous counterparties, cryptocurrency becomes a prime hunting ground for hackers and other criminals.

Below are various types of vulnerabilities individuals may face. Readers should note that while this section covers most known attack types, it is not exhaustive. For those unfamiliar with cryptocurrency, this list of exploits might seem overwhelming, but a large portion consists of "conventional" cyberattacks that have existed throughout the internet era—not unique to the crypto industry.

Social Engineering Attacks

Attacks that rely on psychological manipulation to deceive users into compromising their own security.

-

Phishing: Fake emails, messages, or websites mimic legitimate platforms to steal credentials or recovery phrases.

-

Impersonation scams: Attackers pose as KOLs, project leads, or customer support staff to gain trust and steal funds or sensitive information.

-

Recovery phrase scams: Users are tricked into revealing their seed phrase through fake recovery tools or giveaways.

-

Fake airdrops: Free tokens lure users into unsafe wallet interactions or private key sharing.

-

Fraudulent job offers: Disguised as employment opportunities, but designed to install malware or steal sensitive data.

-

Pump-and-dump schemes: Using social media hype to sell tokens to unsuspecting retail investors.

Telecom and Account Takeover

Exploiting telecom infrastructure or account-level weaknesses to bypass authentication.

-

SIM swapping: Attackers hijack a victim’s phone number to intercept two-factor authentication (2FA) codes and reset account credentials.

-

Credential stuffing: Reusing leaked credentials to access wallets or exchange accounts.

-

Bypassing two-factor authentication: Exploiting weak or SMS-based 2FA to gain unauthorized access.

-

Session hijacking: Stealing browser sessions via malware or insecure networks to take over logged-in accounts.

Hackers once used SIM swapping to take control of the U.S. SEC Twitter account and post fake tweets

Malware and Device Vulnerabilities

Infiltrating user devices to gain wallet access or tamper with transactions.

-

Keyloggers: Record keystrokes to steal passwords, PINs, and recovery phrases.

-

Clipboard hijackers: Replace copied wallet addresses with attacker-controlled ones.

-

Remote Access Trojans (RATs): Allow attackers full control over a victim’s device, including wallets.

-

Malicious browser extensions: Compromised or counterfeit extensions steal data or manipulate transactions.

-

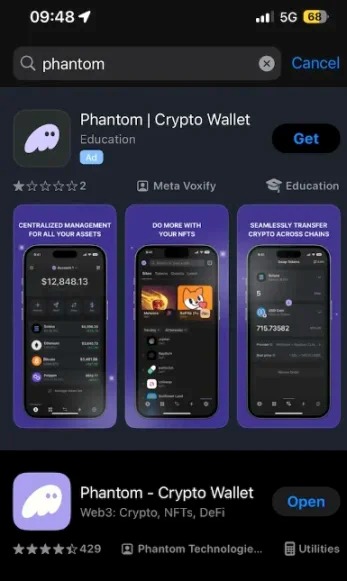

Fake wallets or apps: Counterfeit applications (apps or browsers) that steal funds when used.

-

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks: Intercept and modify communication between users and service providers, especially on insecure networks.

-

Insecure Wi-Fi attacks: Public or compromised Wi-Fi networks can intercept sensitive data during login or transmission.

Fake wallets are a common scam targeting cryptocurrency newcomers

Wallet-Level Vulnerabilities

Attacks targeting how users manage, interact with, or sign transactions from their wallets.

-

Misuse of malicious token approvals: Malicious smart contracts exploit prior token authorizations to drain tokens.

-

Blind signing attacks: Users sign ambiguous transaction terms, leading to fund loss (e.g., from hardware wallets).

-

Seed phrase theft: Recovery phrases leaked via malware, phishing, or poor storage practices.

-

Private key exposure: Insecure storage (e.g., cloud drives or plain text notes) leads to key leaks.

-

Compromised hardware wallets: Tampered or counterfeit devices leak private keys to attackers.

Smart Contract and Protocol-Level Risks

Risks arising from interacting with malicious or vulnerable on-chain code.

-

Rogue smart contracts: Hidden malicious logic triggers upon interaction, resulting in stolen funds.

-

Flash loan attacks: Use of uncollateralized loans to manipulate prices or protocol logic.

-

Oracle manipulation: Attackers alter price feeds to exploit protocols relying on incorrect data.

-

Liquidity exit scams: Creators design tokens/pools where only they can withdraw funds, trapping users.

-

Sybil attacks: Use of multiple fake identities to disrupt decentralized systems, especially governance or airdrop eligibility.

Project and Market Manipulation Scams

Scams related to tokens, DeFi projects, or NFTs.

-

Rug pulls: Project founders disappear after raising funds, leaving worthless tokens.

-

Fake projects: Fraudulent NFT collections trick users into scams or harmful transactions.

-

Dusting attacks: Tiny token transfers used to deanonymize wallets and identify phishing or scam targets.

Network and Infrastructure Attacks

Exploiting frontend or DNS-level infrastructure users depend on.

-

Frontend hijacking / DNS spoofing: Attackers redirect users to malicious interfaces to steal credentials or trigger unsafe transactions.

-

Cross-chain bridge vulnerabilities: User funds stolen during cross-chain transfers.

Physical Threats

Real-world risks including coercion, theft, or surveillance.

-

Physical coercion: Victims forced to transfer funds or reveal recovery phrases.

-

Physical theft: Devices or backups (e.g., hardware wallets, notebooks) stolen to gain access.

-

Shoulder surfing: Observing or recording users entering sensitive data in public or private settings.

Key Vulnerabilities to Watch

While there are many ways users get hacked, some vulnerabilities are more common. Below are the three most critical attack types individuals holding or using cryptocurrency should understand—and how to prevent them.

Phishing (including fake wallets and airdrops)

Phishing predates cryptocurrency by decades. The term emerged in the 1990s to describe attackers “fishing” for sensitive information (usually login credentials) via fake emails and websites. As cryptocurrency emerged as a parallel financial system, phishing naturally evolved to target recovery phrases, private keys, and wallet authorizations.

Crypto phishing is especially dangerous because it offers no recourse: no refunds, no fraud protection, and no customer service to reverse transactions. Once your keys are stolen, your funds are gone. It’s also important to remember that phishing can be just the first step in a broader attack. The real risk may not be the initial loss, but the cascade of damage that follows—for example, stolen credentials enabling attackers to impersonate victims and defraud others.

How Does Phishing Work?

At its core, phishing exploits human trust by presenting fraudulent interfaces or impersonating authority figures to trick users into voluntarily surrendering sensitive information or approving malicious actions. Key distribution methods include:

-

Phishing websites

-

Fake versions of wallets (e.g., MetaMask, Phantom), exchanges (e.g., Binance), or dApps

-

Often promoted via Google ads or shared in Discord/X groups, designed to appear identical to legitimate sites

-

Users prompted to “import wallet” or “recover funds,” leading to theft of recovery phrases or private keys

-

Phishing emails and messages

-

Fake official communications (e.g., “urgent security update” or “account compromised”)

-

Contain links to fake login portals or prompt interaction with malicious tokens or smart contracts

-

Some phishing sites even allow deposits, only for funds to be drained minutes later

-

Airdrop scams: Sending fake token airdrops to wallets (especially on EVM chains)

-

Clicking or trading these tokens triggers malicious contract interactions

-

Secretly request unlimited token approvals or steal native tokens via signed payloads

Phishing Case Study

In June 2023, North Korea’s Lazarus Group attacked Atomic Wallet—one of the most destructive pure phishing attacks in cryptocurrency history. The breach compromised over 5,500 non-custodial wallets, resulting in over $100 million in stolen cryptocurrency—without requiring users to sign any malicious transactions or interact with smart contracts. The attack relied solely on deceptive interfaces and malware extracting recovery phrases and private keys—a textbook case of credential theft via phishing.

Atomic Wallet is a multi-chain, non-custodial wallet supporting over 500 cryptocurrencies. In this incident, attackers launched a coordinated phishing campaign exploiting user trust in the wallet’s support infrastructure, update process, and brand identity. Victims were lured by emails, fake websites, and Trojanized software updates—all mimicking legitimate Atomic Wallet communications.

Tactics used by the hackers included:

-

Fake emails impersonating Atomic Wallet customer support or security alerts, urging immediate action

-

Deceptive websites mimicking wallet recovery or airdrop claim pages (e.g., `atomic-wallet[.]co`)

-

Distribution of malicious updates via Discord, email, and infected forums—redirecting users to phishing pages or extracting login credentials via local malware

Once users entered their 12- or 24-word recovery phrase into these fraudulent interfaces, attackers gained full access to their wallets. This exploit required no on-chain interaction from victims: no wallet connections, no signature requests, no smart contract involvement. Instead, it relied entirely on social engineering and the user’s willingness to restore or verify their wallet on what appeared to be a trusted platform.

Wallet Drainers and Malicious Authorizations

Wallet drainers are malicious smart contracts or dApps designed to extract assets from user wallets—not by stealing private keys, but by tricking users into granting access to tokens or signing dangerous transactions. Unlike phishing attacks that steal credentials, wallet drainers exploit permissions—the very foundation of Web3’s trust model.

As DeFi and Web3 applications became mainstream, wallets like MetaMask and Phantom popularized the concept of “connecting” to dApps. While convenient, this introduced significant attack surface. Between 2021 and 2023, NFT mints, fake airdrops, and certain dApps began embedding malicious contracts within otherwise familiar interfaces. Excited or distracted users would connect their wallets and click “approve,” unaware of what they were authorizing.

Attack Mechanism

Malicious authorizations exploit permission systems in blockchain standards (e.g., ERC-20, ERC-721/ERC-1155). They trick users into granting attackers ongoing access to their assets.

For example, the approve(address spender, uint256 amount) function in ERC-20 tokens allows a “spender” (e.g., a dApp or attacker) to transfer a specified amount from the user’s wallet. Similarly, setApprovalForAll(address operator, bool approved) in NFTs grants an “operator” full rights to transfer all NFTs in a collection.

These approvals are standard for dApps (e.g., Uniswap needs approval to swap tokens), but attackers abuse them maliciously.

How Attackers Gain Authorization

Deceptive prompts: Phishing sites or compromised dApps prompt users to sign a transaction labeled “wallet connection,” “token swap,” or “NFT claim.” In reality, the transaction calls approve or setApprovalForAll with the attacker’s address.

Unlimited approvals: Attackers often request infinite token approvals (e.g., uint256.max) or setApprovalForAll(true), giving them complete control over the user’s tokens or NFTs.

Blind signing: Some dApps require signatures on opaque data, hiding malicious intent. Even hardware wallets like Ledger may display seemingly harmless details (e.g., “approve token”) while concealing the attacker’s true purpose.

After gaining authorization, attackers may immediately drain assets or wait (sometimes weeks or months) to reduce suspicion before acting.

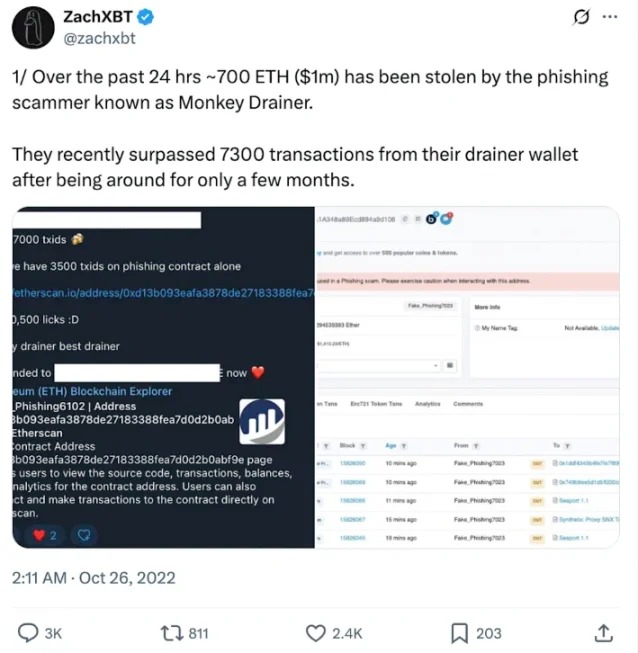

Wallet Drainer / Malicious Authorization Case Study

The Monkey Drainer scam, active primarily in 2022 and early 2023, was a notorious “drainer-as-a-service” phishing toolkit responsible for stealing millions in cryptocurrency—including NFTs—via fake websites and malicious smart contracts. Unlike traditional phishing that relies on stealing recovery phrases or passwords, Monkey Drainer operated through malicious transaction signatures and smart contract abuse, allowing attackers to extract tokens and NFTs without directly stealing credentials. By tricking users into signing dangerous on-chain approvals, Monkey Drainer stole over $4.3 million across hundreds of wallets before shutting down in early 2023.

Noted on-chain detective ZachXBT exposed the Monkey Drainer scam

The toolkit gained popularity among low-skill attackers and was heavily promoted in underground Telegram and dark web communities. It allowed affiliates to clone fake minting websites, impersonate real projects, and configure backends to forward signed transactions to centralized withdrawal contracts. These contracts exploited token allowances, using functions like setApprovalForAll() (NFTs) or permit() (ERC-20 tokens) to grant attacker addresses access to user assets via signed messages—all without the user realizing it.

Notably, the interaction avoided direct phishing—victims were never asked for private keys or recovery phrases. Instead, they interacted with seemingly legitimate dApps, often on minting pages with countdown timers or branding from popular projects. After connecting, users were prompted to sign a transaction they didn’t fully understand, often obscured by generic authorization language or confusing wallet UIs. These signatures did not directly transfer funds but authorized attackers to do so at any time. Once granted, the drainer contract could execute bulk withdrawals within a single block.

A key feature of the Monkey Drainer method was delayed execution—stolen assets were often withdrawn hours or days later to avoid detection and maximize profits. This made it particularly effective against users with high-value wallets or active trading histories, as their approvals blended into normal usage patterns. Notable victims included NFT collectors from projects such as CloneX, Bored Apes, and Azuki.

Although Monkey Drainer ceased operations in 2023—reportedly to “lay low”—the era of wallet drainers continues to evolve, posing an ongoing threat to users who misunderstand or underestimate the power of blind on-chain approvals.

Malware and Device Vulnerabilities

Finally, “malware and device vulnerabilities” refers to a broad and diverse set of attacks using various distribution methods to compromise users’ computers, phones, or browsers by tricking them into installing malicious software. The goal is typically to steal sensitive information (e.g., recovery phrases, private keys), intercept wallet interactions, or give attackers remote control over the victim’s device. In the cryptocurrency space, these attacks often begin with social engineering—such as fake job offers, counterfeit app updates, or files sent via Discord—but quickly escalate into full system compromises.

Malware has existed since the dawn of personal computing. Traditionally, it was used to steal credit card details, harvest login credentials, or hijack systems for spam or ransomware. With the rise of cryptocurrency, attackers shifted focus—from online banking to stealing irreversible crypto assets.

Most malware is not spread randomly—it requires the victim to be tricked into executing it. This is where social engineering comes in. Common distribution methods were listed earlier in this report.

Malware and Device Vulnerability Case Study: 2022 Axie Infinity Recruitment Scam

The 2022 Axie Infinity recruitment scam led to the massive Ronin Bridge hack—a classic example of malware and device exploitation in the crypto world, underpinned by sophisticated social engineering. Attributed to the North Korean hacker group Lazarus, the attack resulted in approximately $620 million in stolen cryptocurrency, making it one of the largest DeFi hacks in history.

The Axie Infinity breach covered by traditional financial media

This hack was a multi-stage operation combining social engineering, malware deployment, and exploitation of blockchain infrastructure vulnerabilities.

Attackers posed as recruiters from a fictitious company, targeting employees of Sky Mavis—the operator of the Ronin Network—via LinkedIn. Ronin Network is an Ethereum-linked sidechain supporting the popular “play-to-earn” blockchain game Axie Infinity. At the time, Ronin and Axie Infinity had market valuations of around $300 million and $4 billion, respectively.

Multiple employees were contacted, but the primary target was a senior engineer. To build trust, attackers conducted multiple rounds of fake job interviews, offering extremely lucrative compensation. They sent the engineer a PDF document disguised as an official job offer. Believing it part of the hiring process, the engineer downloaded and opened the file on a company computer. The PDF contained a RAT (Remote Access Trojan), which, once executed, gave hackers access to Sky Mavis’s internal systems—providing the entry point needed to attack Ronin’s infrastructure.

The breach led to the theft of $620 million (173,600 ETH and $25.5 million USDC), with only $30 million recovered.

How Can We Protect Ourselves?

Although attacks are becoming increasingly sophisticated, they still rely on recognizable red flags. Common warning signs include:

-

“Import your wallet to claim X”: No legitimate service will ever ask for your recovery phrase.

-

Unsolicited direct messages: Especially those offering support, funds, or solutions to problems you didn’t raise.

-

Slight domain misspellings: e.g., metamusk.io vs. metarnask.io.

-

Google ads: Phishing links often appear above legitimate results in search engines.

-

Too-good-to-be-true offers: e.g., “Claim 5 ETH” or “Double your tokens” promotions.

-

Urgency or fear tactics: “Your account is locked,” “Claim now or lose funds.”

-

Infinite token approvals: Users should always specify exact amounts.

-

Blind signature requests: Hex payloads lacking readable explanations.

-

Unverified or obscure contracts: If a token or dApp is new, inspect what you're approving.

-

Urgent UI prompts: Classic pressure tactics like “You must sign now or miss out.”

-

Unexpected MetaMask signature popups: Especially unclear requests, zero-gas transactions, or functions you don’t understand.

Personal Protection Rules

To protect yourself, follow these golden rules:

-

Never share your recovery phrase with anyone, for any reason.

-

Bookmark official websites: Always navigate directly; never search for wallets or exchanges via search engines.

-

Don’t click random airdropped tokens: Especially from projects you didn’t participate in.

-

Avoid unsolicited DMs: Legitimate projects rarely initiate contact… (unless they actually do).

-

Use hardware wallets: They reduce blind signing risks and prevent key exposure.

-

Enable phishing protection tools: Use extensions like PhishFort, Revoke.cash, and ad blockers.

-

Use read-only tools: Services like Etherscan Token Approvals or Revoke.cash show which permissions your wallet holds.

-

Use disposable wallets: Create a new wallet with little or no funds to test mints or links—minimizing potential losses.

-

Diversify holdings: Don’t keep all assets in one wallet.

If you’re already an experienced crypto user, consider these advanced rules:

-

Use dedicated devices or browser profiles for crypto activities, and separate ones for opening links and DMs.

-

Check Etherscan’s token warning labels—many scam tokens are flagged.

-

Cross-verify contract addresses with official project announcements.

-

Inspect URLs carefully: Especially in emails and chats, subtle typos are common. Many messaging apps—and websites—allow hyperlinks, letting someone click www.google.com directly.

-

Pay attention to signatures: Always decode transactions before confirming (e.g., via MetaMask, Rabby, or simulators).

Conclusion

Most users believe vulnerabilities in cryptocurrency are technical and unavoidable—especially those new to the space. While complex attacks may indeed involve novel techniques, the initial steps are often non-technical and targeted at individuals, meaning subsequent breaches could have been prevented.

The vast majority of personal losses in this space do not stem from obscure code bugs or arcane protocol flaws, but from people signing things without reading, importing wallets into fake apps, or trusting a seemingly plausible DM. The tools may be new, but the tricks are ancient: deception, urgency, misdirection.

Self-custody and permissionless access are strengths of cryptocurrency, but users must remember—they also increase risk. In traditional finance, if you’re scammed, you can call the bank. In cryptocurrency, if you’re scammed, the game is likely over.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News