Gavin's Web3 Utopia: The Evolution of Polkadot Smart Contracts and Virtual Machines

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Gavin's Web3 Utopia: The Evolution of Polkadot Smart Contracts and Virtual Machines

Gavin's vision is to build a new decentralized internet world.

Author: Guozi

Polkadot, a veteran blockchain project, is at least known by Web3 practitioners even if they haven't used its products.

Recently, Polkadot has been in the news constantly. The new JAM architecture caught people's attention, and the founder's demonstration of the DOOM game revealed a new landscape for Polkadot, sparking great research interest in me. Given the vast scope of the Polkadot project—including Polkadot chain, Substrate development framework, relay/parachains, etc.—this article focuses on the execution layer, specifically the virtual machine, to walk through its development history, current state, and related information.

Prelude

When Ethereum was first established, Gavin Wood, intrigued by Ethereum, joined its development team. At that time, Ethereum was merely a preliminary framework, and Gavin’s involvement enabled its technical realization. Here are his key contributions to Ethereum:

(1) Completed Ethereum's PoC-1 (Proof of Concept-1); (2) Almost single-handedly built Ethereum’s earliest C++ client; (3) Authored the Yellow Paper, Ethereum’s technical specification; (4) Invented Solidity, a high-level language for smart contract development.

For more historical details, readers can refer to "Everything is Connected: Ethereum and the Future of Digital Finance." Gavin Wood's legendary story is also easily searchable online, so we won’t elaborate here.

Let’s now focus on Solidity and EVM. First, consider this simple Solidity counter example:

pragma solidity ^0.8.3; contract Counter { uint public count; function get() public view returns (uint) { return count; } function inc() public { count += 1; } function dec() public { count -= 1; } }

This example declares a state variable count, which you can think of as a single slot in a database. You can query and modify it via code managing the database. In this case, the contract defines functions—inc, dec, and get—to modify or retrieve the variable value.

After being compiled by the Solidity compiler solc, this generates bytecode (shown below). Once deployed to a node via JSON-RPC, the execution layer reaches consensus before handing it off to the EVM for execution.

6080604052348015600e575f80fd5b506101d98061001c5f395ff3fe608060405234801561000f575f80fd5b506004361061004a575f3560e01c806306661abd1461004e578063371303c01461006c5780636d4ce63c14610076578063b3bcfa8214610094575b5f80fd5b61005661009e565b60405161006391906100f7565b60405180910390f35b6100746100a3565b005b61007e6100bd565b60405161008b91906100f7565b60405180910390f35b61009c6100c5565b005b5f5481565b60015f808282546100b4919061013d565b92505081905550565b5f8054905090565b60015f808282546100d69190610170565b92505081905550565b5f819050919050565b6100f1816100df565b82525050565b5f60208201905061010a5f8301846100e8565b92915050565b7f4e487b71000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000005f52601160045260245ffd5b5f610147826100df565b9150610152836100df565b925082820190508082111561016a57610169610110565b5b92915050565b5f61017a826100df565b9150610185836100df565b925082820390508181111561019d5761019c610110565b5b9291505056fea26469706673582212207b7edaa91dc37b9d0c1ea9627c0d65eb34996a5e3791fb8c6a42ddf0571ca98164736f6c634300081a0033

Let’s examine it again using assembly instructions:

PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH1 0xE JUMPI PUSH0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST POP PUSH2 0x1D9 DUP1 PUSH2 0x1C PUSH0 CODECOPY PUSH0 RETURN INVALID PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH2 0xF JUMPI PUSH0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST POP PUSH1 0x4 CALLDATASIZE LT PUSH2 0x4A JUMPI PUSH0 CALLDATALOAD PUSH1 0xE0 SHR DUP1 PUSH4 0x6661ABD EQ PUSH2 0x4E JUMPI DUP1 PUSH4 0x371303C0 EQ PUSH2 0x6C JUMPI DUP1 PUSH4 0x6D4CE63C EQ PUSH2 0x76 JUMPI DUP1 PUSH4 0xB3BCFA82 EQ PUSH2 0x94 JUMPI JUMPDEST PUSH0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST PUSH2 0x56 PUSH2 0x9E JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x40 MLOAD PUSH2 0x63 SWAP2 SWAP1 PUSH2 0xF7 JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x40 MLOAD DUP1 SWAP2 SUB SWAP1 RETURN JUMPDEST PUSH2 0x74 PUSH2 0xA3 JUMP JUMPDEST STOP JUMPDEST PUSH2 0x7E PUSH2 0xBD JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x40 MLOAD PUSH2 0x8B SWAP2 SWAP1 PUSH2 0xF7 JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x40 MLOAD DUP1 SWAP2 SUB SWAP1 RETURN JUMPDEST PUSH2 0x9C PUSH2 0xC5 JUMP JUMPDEST STOP JUMPDEST PUSH0 SLOAD DUP2 JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x1 PUSH0 DUP1 DUP3 DUP3 SLOAD PUSH2 0xB4 SWAP2 SWAP1 PUSH2 0x13D JUMP JUMPDEST SWAP3 POP POP DUP2 SWAP1 SSTORE POP JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH0 DUP1 SLOAD SWAP1 POP SWAP1 JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x1 PUSH0 DUP1 DUP3 DUP3 SLOAD PUSH2 0xD6 SWAP2 SWAP1 PUSH2 0x170 JUMP JUMPDEST SWAP3 POP POP DUP2 SWAP1 SSTORE POP JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH0 DUP2 SWAP1 POP SWAP2 SWAP1 POP JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH2 0xF1 DUP2 PUSH2 0xDF JUMP JUMPDEST DUP3 MSTORE POP POP JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH0 PUSH1 0x20 DUP3 ADD SWAP1 POP PUSH2 0x10A PUSH0 DUP4 ADD DUP5 PUSH2 0xE8 JUMP JUMPDEST SWAP3 SWAP2 POP POP JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH32 0x4E487B7100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 PUSH0 MSTORE PUSH1 0x11 PUSH1 0x4 MSTORE PUSH1 0x24 PUSH0 REVERT JUMPDEST PUSH0 PUSH2 0x147 DUP3 PUSH2 0xDF JUMP JUMPDEST SWAP2 POP PUSH2 0x152 DUP4 PUSH2 0xDF JUMP JUMPDEST SWAP3 POP DUP3 DUP3 ADD SWAP1 POP DUP1 DUP3 GT ISZERO PUSH2 0x16A JUMPI PUSH2 0x169 PUSH2 0x110 JUMP JUMPDEST JUMPDEST SWAP3 SWAP2 POP POP JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH0 PUSH2 0x17A DUP3 PUSH2 0xDF JUMP JUMPDEST SWAP2 POP PUSH2 0x185 DUP4 PUSH2 0xDF JUMP JUMPDEST SWAP3 POP DUP3 DUP3 SUB SWAP1 POP DUP2 DUP2 GT ISZERO PUSH2 0x19D JUMPI PUSH2 0x19C PUSH2 0x110 JUMP JUMPDEST JUMPDEST SWAP3 SWAP2 POP POP JUMP INVALID LOG2 PUSH5 0x6970667358 0x22 SLT KECCAK256 PUSH28 0x7EDAA91DC37B9D0C1EA9627C0D65EB34996A5E3791FB8C6A42DDF057 SHR 0xA9 DUP2 PUSH5 0x736F6C6343 STOP ADDMOD BYTE STOP CALLER

From a compiler theory perspective, the execution flow looks like this: Solidity source code -> lexer -> parser -> compilation -> bytecode -> VM -> interpretation.

Yes, it's just a new programming language in the computing industry, but back then, it was truly groundbreaking. Two years after joining Ethereum’s development, the network launched as planned. If Vitalik created Ethereum’s body, Gavin gave it its soul. Bitcoin is an electronic payment system, while Ethereum made blockchains programmable. With its slogan “World Computer,” everything changed.

Web 3.0

While still serving as co-founder and CTO of Ethereum, Gavin published an article titled “DApps: What Web 3.0 Looks Like”[1] on April 17, 2014, on his blog “Insights into a Modern World,” outlining his vision of Web3.0 and its four core components. The impact and popularity of the Web3.0 concept are evident to all. Gavin not only excelled technically but also demonstrated remarkable foresight. For background on the history and debates around Web3.0, see the Wikipedia entry [2]. American entrepreneur and venture capitalist Nova Spivack [3] suggests extending the definition of Web3.0 to reflect how various tech trends are maturing. Key aspects include:

• Ubiquitous connectivity: Broadband internet expansion and mobile device internet access (e.g., tablets).

• Network computing: “SaaS” business models, web service interoperability, distributed computing, grid computing, and utility computing (“cloud computing”).

• Open technologies: Open APIs and protocols, open data formats, open-source software platforms, and open data (e.g., Creative Commons, open data licenses).

• Open identity: OpenID, open reputation, cross-domain identity, and personal profiles.

• Smart networks: Semantic web technologies such as RDF, OWL, SWRL, SPARQL, semantic application platforms, and declarative data storage.

• Distributed databases: Worldwide Database (“World Wide Database”) realized through semantic web technologies.

• Intelligent applications: Natural language processing, machine learning, machine reasoning, autonomous agents.

By the end of 2015, Gavin left Ethereum.

He then founded Parity Technologies and developed an Ethereum client written in Rust, which briefly dominated the Ethereum wallet market. We don’t know Gavin’s exact reasons for leaving Ethereum, but what we do know is that his vision was to build a completely new decentralized internet world.

"Ethereum was an experiment for me—a prototype to test whether the technology was viable. Ethereum was my school, and I graduated. Now I want to try doing more."

"Actually, what I learned most from Ethereum wasn’t technical (Ethereum had a dedicated research team handling technical details), but social experience. Governance was one of them. I believe enhancing a system’s capabilities through governance is crucial—it would be a revolutionary new feature—and that’s precisely what Ethereum didn’t do."

During his time at Ethereum, Gavin was always a practitioner, not a designer, and he had long been brewing new innovations.

The Birth of Polkadot

A year later, Gavin solved a long-standing puzzle and released the Polkadot whitepaper in 2016. Many know that besides addressing scalability, Polkadot aims to enable communication among isolated blockchains—cross-chain interoperability. But when thinking about Polkadot, the key point to remember is: sharding. Because taken to the extreme, sharding essentially becomes Polkadot itself.

As Gavin himself put it:

"The design logic behind Polkadot wasn't directly inspired by interoperability. We were waiting for Ethereum’s sharding to launch. But sharding never materialized, and still hasn’t. So I decided to create a more scalable 'Ethereum,' pushing the concept of sharding to an extreme—why bother with shards? Just design independent chains. With this approach, different chains can exchange information, ultimately communicating via a shared consensus layer."

How should we understand sharding? Let’s start with Ethereum’s dilemma. Performance issues have long plagued Ethereum. In 2018, CryptoKitties caused severe congestion, increasing transaction times and fees. It’s like a bank with only one slow window—when too many customers arrive, long queues form.

But if the bank opens multiple windows, transactions could be processed simultaneously, eliminating lines. This is the basic logic of sharding: dividing network nodes into separate regions called shards, distributing massive transactions across them, greatly improving efficiency.

In Polkadot, each shard carries core logic and allows parallel transactions and data exchange, linking multiple blockchains into one network.

Polkadot isn’t just comparable to—or even surpassing—Ethereum 2.0; its true innovation lies in this: in Polkadot, there can be many Ethereums. It’s no longer just a single blockchain. “Polkadot wants to provide a truly open and free platform for various social innovations.”

This is the ideal of Web3, the ideal of Polkadot, and Gavin’s ideal.

Polkadot 1.0

The Polkadot relay chain itself doesn’t support smart contracts, but its connected parachains [4] can define their own state transition rules and thus offer smart contract functionality. Unlike other ecosystems, within Polkadot’s stack, parachains and smart contracts exist at different layers: smart contracts sit atop parachains. Parachains are typically described as Layer 1 blockchains—with the difference being they don’t need to build their own security and can upgrade and interoperate.

Polkadot offers developers flexibility in building smart contracts, supporting both EVM-executed Solidity contracts and Wasm-based contracts using ink!:

EVM-Compatible Contracts

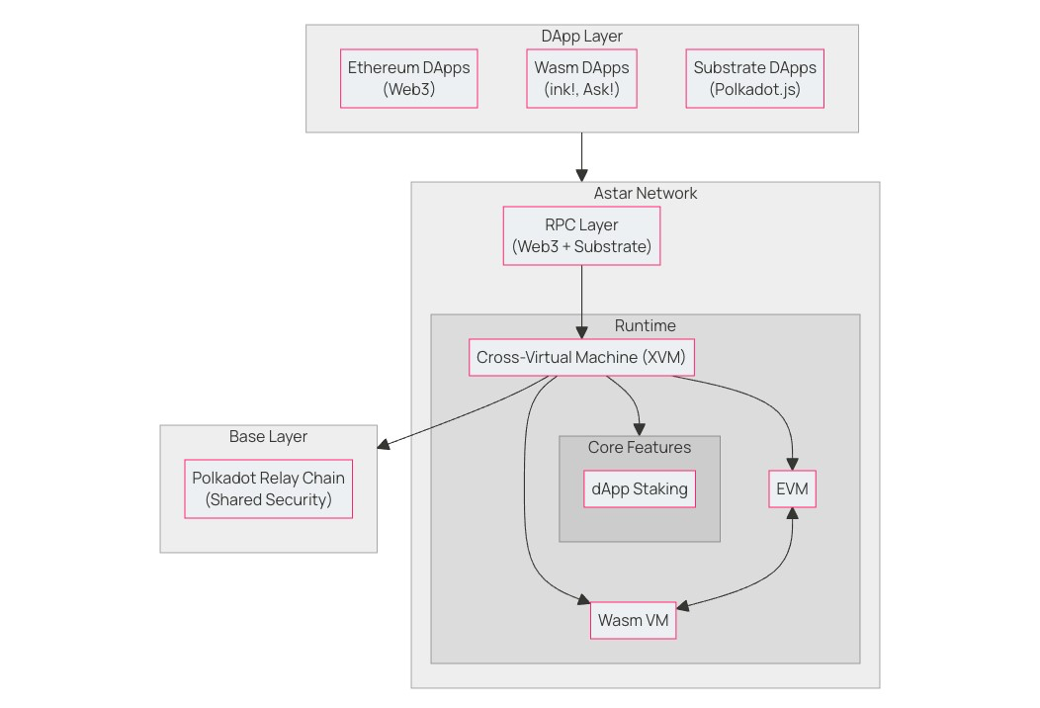

Polkadot’s ecosystem supports the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) thanks to Frontier [5], a toolkit. Frontier enables Substrate-based blockchains to natively run Ethereum smart contracts and interact seamlessly with the Ethereum ecosystem via Ethereum-compatible APIs/RPCs. Contracts are written in languages like Solidity or Vyper. EVM is widely standardized across blockchains, including Polkadot parachains like Astar, Moonbeam, and Acala. This compatibility allows contracts to be deployed across multiple networks with minimal modifications, benefiting from a mature and extensive developer ecosystem.

For example: Astar [6], a key smart contract platform on Polkadot, uses a unique multi-VM approach supporting both EVM and WebAssembly (Wasm) smart contracts. This dual VM support lets developers choose their preferred programming environment while maintaining full Ethereum compatibility. The platform’s runtime [7] is built on Substrate using FRAME, combining key components from the Polkadot-SDK and custom modules for its unique features.

These chains often use off-the-shelf contract modules and add extra innovations. Examples include: Phala [8]: Uses contract modules within trusted execution environments for confidential smart contract execution and interoperability. Aleph Zero [9]: Uses contract pallets in zero-knowledge environments. t3rn [10]: Uses contract modules as building blocks for multi-chain smart contract execution. See official documentation for more EVM-compatible parachains like Aster, Moonbeam, and Acala: Parachain Contracts [11]

Wasm (ink!) Contracts:

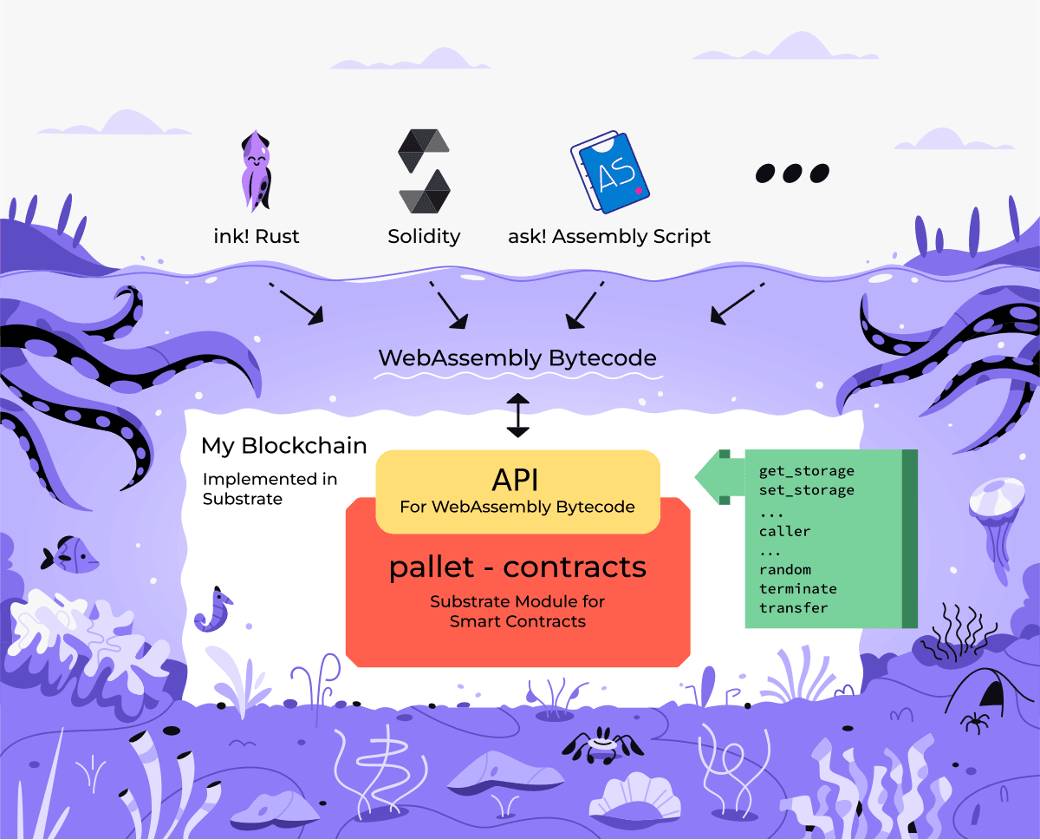

Polkadot provides the Contracts module [12] via the FRAME framework, using WebAssembly as the contract runtime. In theory, any language compilable to Wasm can be used for smart contract development, but for optimization and convenience, Parity introduced ink! [13] specifically.

Before discussing ink!, we must clarify Substrate [14] and its Contracts module (pallet-contracts). Substrate is a blockchain-building framework, capable of creating standalone blockchains or those connecting to Kusama [15] or Polkadot [16] as parachains.

Substrate includes many modules, called pallets in Substrate terminology. It comes with a set of pallets meeting common modern blockchain requirements—staking, fungible tokens, NFTs, governance, etc.

Substrate also includes a pallet for smart contracts called the Contracts pallet. If developing a parachain on Substrate, adding smart contract functionality is easy by including this pallet. This module acts as the execution environment, taking WebAssembly files as input. Smart contracts for this module must be compiled into WebAssembly (Wasm) target architecture.

Where does ink! come in? ink! is a programming language—in fact, an embedded domain-specific language (eDSL) based on the popular Rust programming language. This means you can use standard Rust syntax plus additional elements tailored for smart contracts. The Contracts pallet receives these ink! contracts and executes them securely. In short:

With ink!, you can write smart contracts in Rust for blockchains built with Substrate that include the Contracts pallet.

ink! doesn’t create a new language; it’s standard Rust with a defined “contract format” and special #[ink(...)] attribute macros. These macros tell the ink! compiler what each part of the Rust smart contract represents, enabling it to generate Wasm bytecode compatible with the Polkadot SDK. Since ink! contracts compile to Wasm, they execute via sandboxing, offering high speed, platform independence, and enhanced security.

Here’s a simple ink! contract. This contract stores a boolean value. Upon creation, it sets the value to true. It exposes two functions: one to read the current value (fn get()) and another to toggle it (fn flip()).

#[ink::contract] mod flipper { #[ink(storage)] pub struct Flipper { value: bool, } impl Flipper { #[ink(constructor)] pub fn new(init_value: bool) -> Self { Self { value: init_value } } #[ink(message)] pub fn flip(&mut self) { self.value = !self.value; } #[ink(message)] pub fn get(&self) -> bool { self.value } }}

It offers similar capabilities to Solidity: Storage, Message, Errors, Events, etc. For developers, this means they can use ink! to write smart contracts or opt for other languages: Solang compiler [17] for Solidity and ask! [18] for AssemblyScript (below):

import { env, Pack } from "ask-lang";import { FlipEvent, Flipper } from "./storage";@contractexport class Contract { _data: Pack<Flipper>; constructor() { this._data = instantiate<Pack<Flipper>>(new Flipper(false)); } get data(): Flipper { return this._data.unwrap(); } set data(data: Flipper) { this._data = new Pack(data); } @constructor() default(flag: bool): void { this.data.flag = flag; } @message({ mutates: true }) flip(): void { this.data.flag = !this.data.flag; let event = new FlipEvent(this.data.flag); // @ts-ignore env().emitEvent(event); } @message() get(): bool { return this.data.flag; }}

Adding new languages isn’t hard—just need a WebAssembly-capable language compiler, then implement the Contracts pallet API.

Currently, this API includes about 15–20 functions covering anything a smart contract might need: storage access, cryptographic functions, environmental info (like block number), functions for random numbers or self-termination, etc. Not all need implementation—ink!’s “Hello, World!” requires only six API functions. The following diagram illustrates this relationship:

Choosing ink! and the Contracts pallet over EVM offers several advantages. Here are some detailed in this article:

• ink! is just Rust—you can use all standard Rust tools: clippy, crates.io [19], IDEs, etc.

• Rust incorporates decades of language research, making it safe and fast. It also learns from older smart contract languages like Solidity, incorporating better defaults—for instance, overflow checks disabled by default, functions private by default.

• Rust is an amazing language, ranked the most loved programming language on StackOverflow for seven consecutive years (source [20]).

• If you're a company hiring smart contract developers, you can draw from the much larger Rust ecosystem compared to Solidity’s niche market.

• ink! is native to Substrate, using similar primitives and the same type system.

• Migration path from contracts to parachains is clear. Since both ink! and Substrate use Rust, developers can reuse most code, tests, front-end, and client code.

• WebAssembly is an industry standard, continuously improved by major companies like Google, Apple, Microsoft, Mozilla, and Facebook.

• WebAssembly expands the language options for smart contract developers—Rust, C/C++, C#, TypeScript, Haxe, Kotlin, etc. You can use any familiar language. This design is more forward-looking than tight coupling between language and execution architecture.

For more on this section, read “What is Parity’s ink!?” [21].

Polkadot 2.0 / JAM

On February 28, Gavin Wood publicly demoed running the DOOM game on JAM during the JAM Tour Shanghai stop—an historic moment for blockchain. JAM transforms blockchain from just a network into a powerful supercomputing platform capable of running conventional software like DOOM, delivering strong computational power and low latency.

Setting aside other aspects, let’s focus on the virtual machine. Based on my recent reading of PolkaVM’s source code, this is real—the key is that PolkaVM runs a host that exposes interfaces upward, then executes a guest RISC-V version of DOOM inside the VM.

Source code here:

https://github.com/paritytech/polkavm/tree/master/examples/doom

Let’s examine the key components of this new smart contract solution:

Revive Pallet

The Revive Pallet [22] adds runtime functionality to deploy and execute PolkaVM smart contracts. It’s a heavily modified fork of pallet_contracts. These contracts can be written in any language compilable to RISC-V. Currently, only Solidity (via revive [23]) and Rust (see Rust examples in the fixtures directory) are officially supported.

At the contract language level, it’s Ethereum-compatible: write contracts in Solidity and interact with nodes using Ethereum JSON RPC and wallets like MetaMask. Under the hood, contracts are recompiled from YUL to RISC-V to run on PolkaVM instead of EVM. To simplify, a customized REMIX [24] web frontend can compile contracts into RISC-V and deploy them to the Westend Asset Hub Parachain [25].

Revive

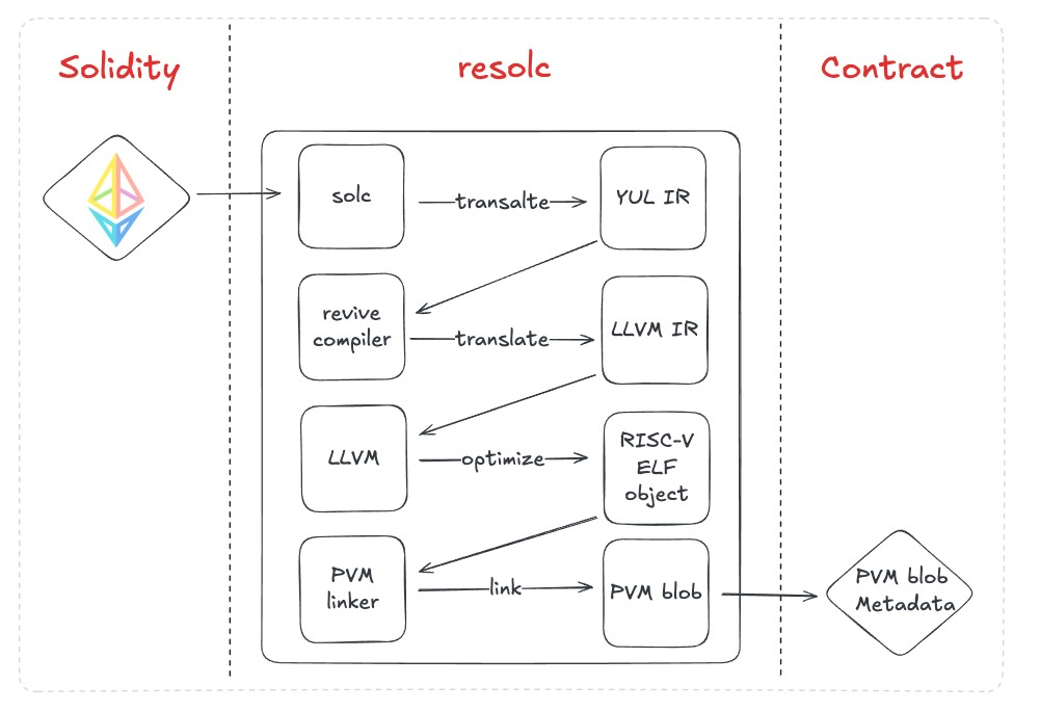

Revive [26] is the umbrella term for the “Solidity to PolkaVM” compiler project, encompassing multiple components (e.g., YUL frontend and the resolc executable). resolc is the name of the single-entry-point binary frontend, transparently using all revive components to generate compiled contract artifacts. It compiles Solidity contracts into RISC-V code executable by PolkaVM, enabling Solidity contracts to run on Polkadot.

This requires a compiler. Its workflow uses the original solc compiler, then recompiles its intermediate representation (YUL) into RISC-V. LLVM [27], a popular and powerful compiler framework, serves as the backend, handling optimization and RISC-V code generation. revive primarily handles lowering the generated YUL IR from solc to LLVM IR.

This approach strikes a good balance between high Ethereum compatibility, solid contract performance, and feasible engineering effort. Compared to building a full Solidity compiler, this task is significantly smaller. By choosing this method, all quirks and oddities across Solidity versions are supported.

PolkaVM

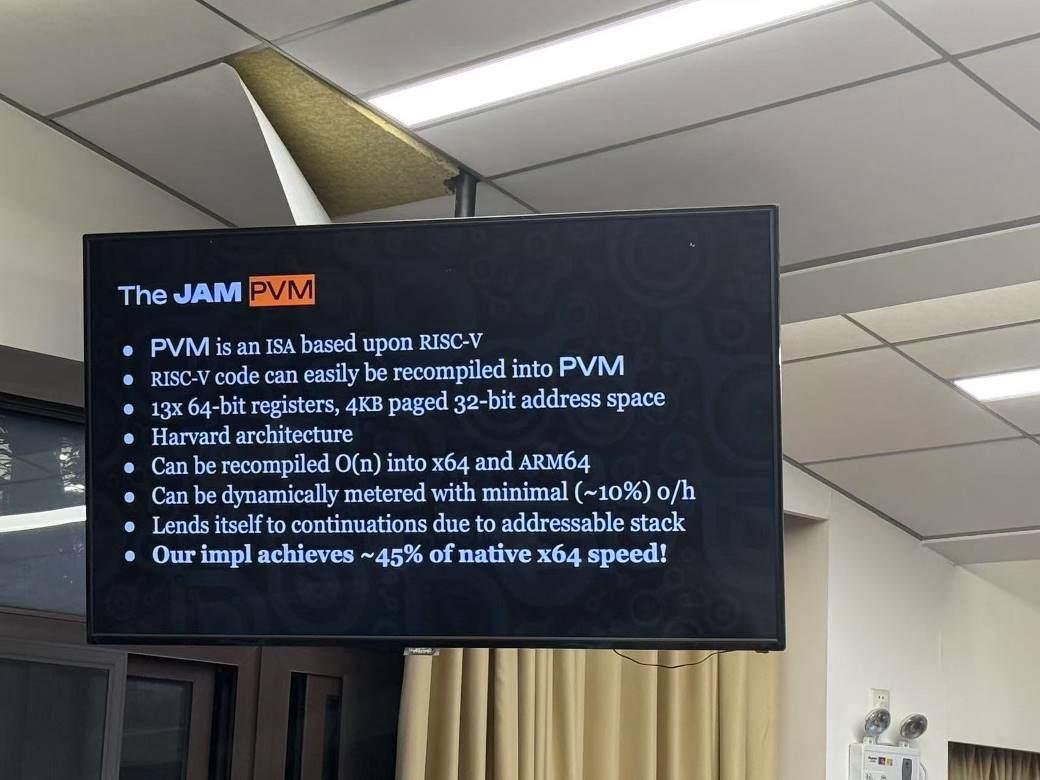

PolkaVM [28] is a general-purpose user-level VM based on RISC-V—the most obvious departure from competing technologies. Instead of EVM, a new custom VM executes contracts. Currently, a PolkaVM interpreter is included within the runtime. Future updates will include a full PolkaVM JIT running inside the client.

• Secure and sandboxed by default. Code running in the VM should operate in a separate process and cannot access the host system—even if an attacker gains full remote code execution inside the VM.

• Fast execution. Runtime performance should rival top-tier WebAssembly VMs, at least within the same order of magnitude.

• Fast compilation, ensuring O(n) single-pass compilation. Loading new code into the VM should be nearly instantaneous.

• Low memory footprint. Baseline memory overhead per concurrent VM instance should not exceed 128KB.

• Small binaries. Programs compiled for this VM should occupy minimal space.

• No wasted virtual address space. The VM shouldn’t pre-allocate GBs of virtual address space for sandboxing.

• Fully deterministic. Given identical inputs and code, execution must always produce identical outputs.

• High-performance asynchronous gas metering. Gas metering should be cheap, deterministic, and reasonably accurate.

• Simple. A programmer should be able to write a fully compatible interpreter for this VM in under a week.

• Versioned operational semantics. Any future changes to observable semantics for client programs will be versioned and require explicit opt-in.

• Standardized. There should be a complete specification describing the customer-visible operational semantics of this VM.

• Cross-platform. On unsupported OSes and platforms, the VM will run in interpreted mode.

• Minimal external dependencies. The VM should be largely independent, compile quickly, and resist supply-chain attacks.

• Built-in tools for debugging and profiling.

Two fundamental differences from EVM:

• Register machine – EVM is a stack machine, meaning function arguments are passed on an infinite stack. PolkaVM, based on RISC-V, is a register machine, passing parameters through a finite set of registers. This main benefit makes hardware translation more efficient. The number of registers is carefully chosen—fewer than the notoriously register-starved x86-64 ISA. Reducing the NP-hard register allocation problem to a simple 1-to-1 mapping is the secret behind PolkaVM’s fast compilation times.

• Reduced word size – EVM uses 256-bit words, meaning every arithmetic operation must handle these large numbers, making meaningful operations very slow as they translate into many native instructions. PolkaVM uses 64-bit words, natively supported by underlying hardware. When converting Solidity contracts via YUL (#Revive), 256-bit arithmetic is still used because YUL is too low-level to automatically convert integer types. However, you can write contracts in other languages and call them seamlessly from Solidity—imagine a system where business logic is in Solidity but core infrastructure is in a faster language, akin to Python relying on C modules for heavy lifting.

Summary

Smart Contract Programming Languages

The number of smart contract languages grows yearly. Choosing the first language can be challenging, especially for beginners. The choice mainly depends on your preferred ecosystem, though some languages work across multiple platforms. Each language has pros and cons—this article won’t detail them all.

Why so many contract languages? Possible reasons: 1) Existing languages fail to meet chain-specific needs; 2) Better performance, security, cost; 3) Personal taste :)

I have no bias toward any contract language. Below are excerpts from different voices, offering diverse insights from both user and language/VM design perspectives.

• Why not use Solidity? Solidity is a celebrated pioneer but constrained by many EVM historical quirks. It lacks common features expected by programmers, has a relatively weak type system, and lacks a unified tool ecosystem. In Sway, we let you design smart contracts using a full suite of modern tools. You get a feature-rich language with generics, algebraic types, and trait-based polymorphism. You also get an integrated, unified, easy-to-use toolchain with LSP server for code completion, formatter, documentation generator, and everything needed to run and deploy contracts—making it easy to achieve your goals. Our expressive type system helps catch semantic errors, we provide good defaults, and perform extensive static analysis checks (e.g., mandatory enforcement of checks, effects, interactions) so you can ensure secure, correct code at compile time using java.lang.Integer.pattern.

via https://docs.fuel.network/docs/sway/

• Why not use Rust? While Rust is an excellent systems programming language (Sway itself is written in Rust), it’s not ideal for smart contract development. Rust excels by enabling zero-cost abstractions and complex borrow-checker memory models, achieving impressive runtime performance for complex programs without garbage collection. On blockchains, execution and deployment costs are scarce resources. Low memory usage and short execution times matter. Complex memory management often becomes too expensive to justify, making Rust’s borrow checker a burden with no benefits. General-purpose programming languages usually aren’t suited for such environments since they’re designed assuming general-purpose computing. Sway tries to bring Rust’s other advantages—modern type system, safety practices, good defaults—to smart contract developers by providing familiar syntax and features tailored to blockchain-specific needs.

via https://docs.fuel.network/docs/sway/

• Clarity code is interpreted and executed exactly as written. Solidity and other languages are compiled into bytecode before being committed to the chain. Compiling smart contract languages poses two dangers: First, compilers add complexity. Compiler bugs may result in bytecode differing from expectations, risking vulnerabilities. Second, bytecode is not human-readable, making it hard to verify what a smart contract actually does. Ask yourself: Would you sign a contract you couldn’t read? If your answer is no, why treat smart contracts differently? With Clarity, what you see is what you get.

via https://docs.stacks.co/concepts/clarity#clarity-is-interpreted-not-compiled

Virtual Machines and Instruction Sets

From the well-known JVM to EVM’s heuristic rise in blockchain, I’m aware of dozens of virtual machines. Different VMs implement differently, but the core interpreter is often the most fundamental execution method, especially alongside Just-In-Time (JIT) or Ahead-Of-Time (AOT) compilation. Interpreters remain widely used for code execution, responsible for parsing and executing bytecode.

Interpreter Example

Below is a minimal example demonstrating the essence of an interpreter, without considering optimizations.

use std::collections::VecDeque; #[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)] enum OpCode {Push(i32), Add, Sub, Mul, Div, Print} struct Interpreter { stack: Vec<i32>, } impl Interpreter { fn new() -> Self { Interpreter { stack: Vec::new() } } fn run(&mut self, bytecode: VecDeque<OpCode>) { for op in bytecode { match op { OpCode::Push(value) => self.stack.push(value), OpCode::Add => self.binary_op(|a, b| a + b), OpCode::Sub => self.binary_op(|a, b| a - b), OpCode::Mul => self.binary\_op(|a, b| a * b), OpCode::Div => self.binary\_op(|a, b| a / b), OpCode::Print => { if let Some(value) = self.stack.last() { println!("{}", value); } } } } }fn binary_op(&mut self, op: fn(i32, i32) -> i32) { if self.stack.len() < 2 { panic!("Stack underflow!"); } let b = self.stack.pop().unwrap(); let a = self.stack.pop().unwrap(); self.stack.push(op(a, b)); }} fn main() { let bytecode = VecDeque::from(vec!\[ OpCode::Push(10), OpCode::Push(20), OpCode::Add, OpCode::Push(5), OpCode::Mul, OpCode::Print, ]); let mut interpreter = Interpreter::new(); interpreter.run(bytecode); }

Each instruction consists of an opcode, possibly with parameters. The interpreter uses a stack to store computation data, with only six instructions.

Instruction Set Classification

From the above interpreter example, the number and extensibility of instructions determine a VM’s direction. In my analysis, VMs can be categorized into four types based on instruction sets:

1. Proprietary instruction sets like EVM, requiring massive redundant work—compiler development, instruction design, etc. Before EIP-3855 [29], EVM already had 141 instructions, and more keep being added.

2. WASM, ready-to-use, supports multiple languages but is relatively heavy—a point also raised in Polkadot documentation. WASM’s advantage lies in natural multi-language support. If a chain only needs to run logic and crudely write state into account storage slots, WASM fits well—fast development, rapid integration. But its drawback is that instructions aren’t blockchain-specific, making it hard to support special capabilities or trim down (over 150 instructions [30]).

Note also Solana’s SVM, which executes BPF instructions. Arbitrary programming languages can compile into BPF dynamic libraries—though relatively niche compared to WASM.

3. Based on RISC-V instruction set—e.g., PolkaVM and many zkVM projects: ceno, eigen zkvm, jolt, mozak vm, nexus, o1vm, openvm, powdrVM, risc0, sp1, sphinx, etc. I haven’t studied them all yet, but from what I know, PolkaVM and Nexus zkVM implement general RISC-V instruction interpretation. Most languages, when compiled via GCC or LLVM, can output RISC-V instructions—opening up language-level possibilities and laying groundwork for future multi-language support. Base RV32I has 47 instructions, optional extensions. Compared to x86’s 3000+ instructions, it’s truly minimalist.

4. Interpreted languages—e.g., Stacks’ Clarity (Lisp), AO’s Lua, Mina’s TypeScript. So in summary, if EVM represents proprietary instructions on the left and open WASM on the right, RISC-V offers a balanced option for secondary development. First, major compilers already support it, with many reference implementations. Second, it’s easy to design custom instructions on top.

Extra: Exploring the Future of Multi-Chain Smart Contracts

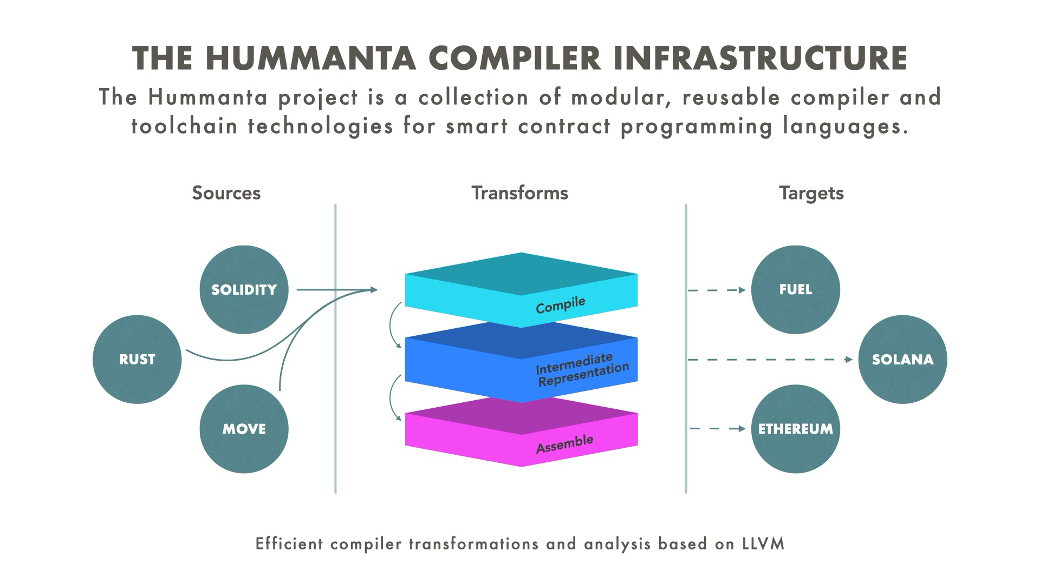

As blockchain ecosystems diversify, more projects introduce their own smart contract languages (e.g., Solidity, Move, Cairo, Sway) to support unique features. While this innovation enriches the tech stack, it brings new learning curves and compatibility challenges. A core question emerges: Can mature Solidity contracts be seamlessly deployed on emerging blockchains?

To address this, we’ve teamed up with several researchers passionate about compiler technology to launch the Hummanta compiler project. This initiative aims to break down chain barriers, enabling cross-chain compilation of smart contract languages, supporting conversion of Solidity, Move, Cairo, Sway, etc., into multiple VM environments—including EVM and emerging VMs: PolkaVM, SolanaVM, MoveVM, FuelVM, and others.

Project Progress

We’re advancing this vision in three directions:

1. Syntax and instruction set standardization: Systematically organizing syntax definitions across languages and VM instruction sets to lay the foundation for cross-chain compilation.

2. Compiler toolchain development: Building parsers with LALRPOP [31], leveraging Cranelift [32]/LLVM for code generation, supporting multi-language to multi-target bytecode conversion.

3. Integrated development experience: Developing the Hummanta CLI tool [33] (similar to Cargo) to support end-to-end workflows from compilation to deployment.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News