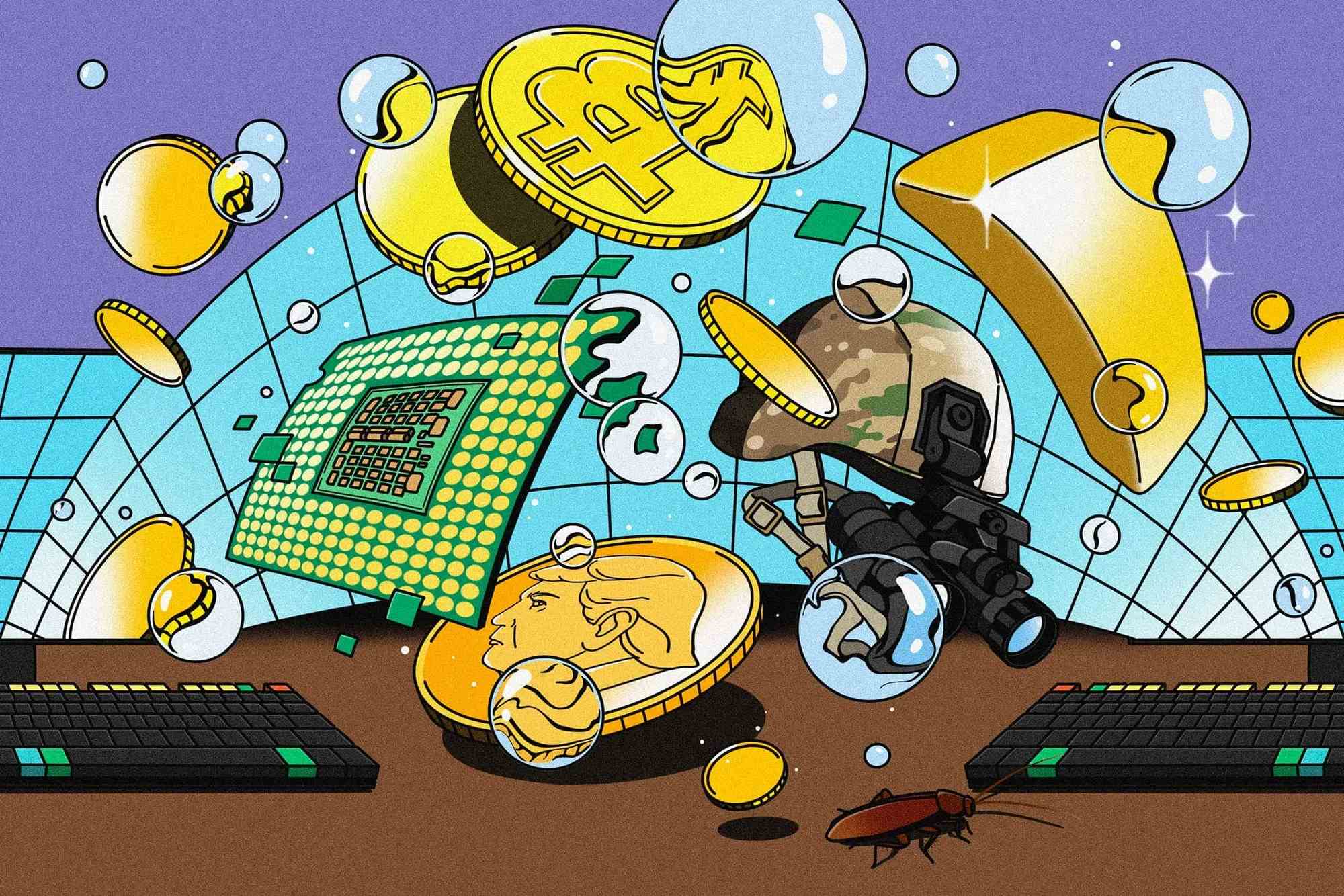

Was it worth $14 million for Jump Trading to gain 0.07 milliseconds?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Was it worth $14 million for Jump Trading to gain 0.07 milliseconds?

Jump Trading's target is not people, but computers.

In the ever-changing financial markets, speed is money. Two-thirds the speed of light may seem like a blink to ordinary people, but for high-frequency trading firms, it could determine the success or failure of a trade. Today, let's talk about the "speed war" in high-frequency trading and the stories of companies spending heavily for microsecond advantages.

To gain just 0.07 milliseconds over their competitors, one company spent $14 million—a mere 1/5700th of a blink!

The Value of 0.07 Milliseconds: A Battle of Speed

Imagine that a blink takes 0.4 seconds, yet a high-frequency trading firm named Jump Trading spent $14 million simply to improve data transmission speed by 0.07 milliseconds (i.e., 0.00007 seconds). The company purchased a 120,000-square-meter plot of land directly opposite the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), the world’s largest futures exchange—not to build an office or for feng shui—but to erect microwave communication towers, ensuring trading signals reach the exchange as quickly as possible.

According to a similar case involving Nasdaq’s microwave towers, this improvement would yield only 0.07 milliseconds. Though seemingly insignificant, for high-frequency trading, such a tiny time difference can be the source of massive profits. Traditional fiber-optic transmission travels at about 2/3 the speed of light, while microwave transmission approaches light speed—about 50% faster than fiber optics. More importantly, fiber-optic cables are rarely laid in straight lines, whereas microwaves can take shortcuts.

For human traders, the difference between 0.00007 seconds and 0.00014 seconds is meaningless—after all, it takes the human eye and brain 0.15 to 0.225 seconds to process visual information. But Jump Trading isn’t targeting humans; their goal is computers—algorithmic trading systems capable of making decisions and executing trades within microseconds.

High-Frequency Trading: Buying and Selling Within 0.2 Seconds

Jump Trading is a typical high-frequency trading (HFT) firm. When major news breaks—such as corporate earnings reports, central bank interest rate changes, or CPI data—their servers use complex algorithms to predict stock price movements over the next few seconds, automatically executing buy or sell orders. Given the extremely short trading windows, even minor price fluctuations can generate substantial profits or reduce losses. Thus, gaining information faster and executing trades ahead of competitors is the core pursuit of every HFT firm.

This isn't the first time Jump Trading has spent big on speed. As early as 2013, they acquired a former NATO-used microwave tower in the UK, solely to transmit data faster to the London Metal Exchange. Speed has become the lifeline of high-frequency trading.

The Pinnacle of Trading Speed: The Ulta Earnings Case

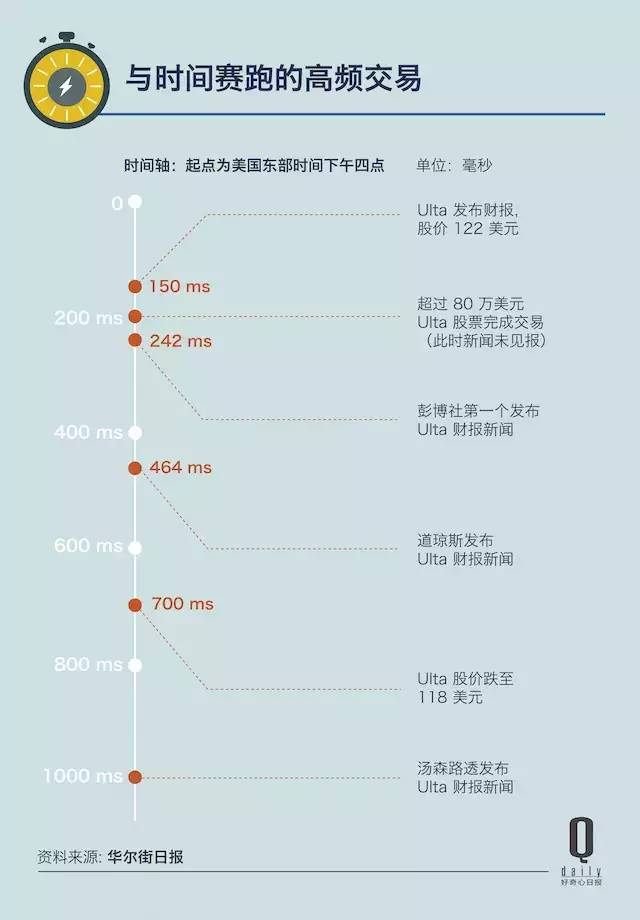

The Wall Street Journal once revealed a classic case illustrating just how fast high-frequency trading can be. On December 5, 2014, at 4:00 PM Eastern Time, cosmetics retailer Ulta released its earnings report with a stock price of $122. What followed unfolded in milliseconds:

-

• 4:00:00.15: PR Newswire sent the earnings press release to HFT firms and terminals like Bloomberg.

-

• 4:00:00.20: HFT firms sold $800,000 worth of Ulta shares at $122.

-

• 4:00:00.242: Bloomberg was the first to publish the Ulta earnings news.

-

• 4:00:00.464: Dow Jones published related news.

-

• 4:00:00.7: Ulta’s stock price had already dropped to $118.

-

• 4:00:01: Thomson Reuters finally released the earnings report.

At this point, only 0.85 seconds had passed—far too little time for any human trader to read the headline, yet HFT computers had already completed their trades. Humans simply cannot compete with such speed.

This event drew scrutiny from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), putting regulatory pressure on PR Newswire. Although CEO Cathy Baron Tamraz insisted, “We didn’t do anything wrong,” public backlash and potential consequences led the company, after consulting with major shareholder Warren Buffett, to discontinue its practice of sending financial data directly to select paying clients. Today, HFT firms must wait for Bloomberg to publish information before acting—a delay of approximately 0.192 seconds. While seemingly fairer, the race for speed among machines has never ceased.

Technological Arms Race: Microwaves, Fiber Optics, and Lasers

In the HFT "speed war," cutting-edge technologies are fully deployed. Fiber-optic networks are typically preferred for long-distance high-speed connections, but their speed is limited by the medium (around 200,000 meters per second) and often follow railway routes, meaning they’re not direct. Microwave signals travel through air close to light speed (300,000 meters per second). By installing relay towers on mountaintops or tall buildings, firms can minimize transmission distance.

Jump Trading’s microwave towers across from the CME aim for maximum speed. In fact, the CME’s own data center relies on microwave transmission. In 2015, McKay sold land to the CME for a data center. Recently, DuPage County near Aurora approved McKay to build a new microwave tower—188 meters closer to the CME trading hub—again aiming to save just 0.00007 seconds.

However, microwave transmission is not perfect. Signal quality is vulnerable to bad weather, especially rain, with reliability around 90%. Additionally, microwave bandwidth is limited—Anova’s single microwave tower offers only 100 Mbps, while fiber optics can reach up to 1,000 times that capacity. Therefore, microwaves are better suited for small-data transactions where speed is critical, while fiber optics are ideal for transmitting large volumes of data, such as corporate earnings reports.

Beyond microwaves and fiber optics, some firms pursue even more extreme solutions. Starting in 2010, Spread Networks spent $300 million digging a tunnel through the Appalachian Mountains, reducing data transmission time by about 3 milliseconds. There are also trans-Arctic undersea cable projects—including "Arctic Fibre," "Arctic Link," and Russia’s "ROTACS"—with total investment of around $1.5 billion, aiming to cut data transmission time between London and Tokyo from 0.23 seconds to 0.17 seconds, shortening the route by nearly 8,000 kilometers.

Even more promising is laser communication. Anova installed laser towers between Manhattan and the data centers of the NYSE and Nasdaq, using infrared lasers to transmit data at twice the speed of fiber optics, with bandwidth reaching 2 Gbps, and minimal weather interference. Anova CEO Michael Persico revealed they’ve also installed equipment at 1275 K Street in Washington D.C. to capture U.S. government economic data the moment it’s released. However, laser transmission requires line-of-sight, requiring solutions for signal accuracy affected by building sway.

The Value of High-Frequency Trading: Efficiency or Profit-Seeking?

What does high-frequency trading actually bring? Larry Tabb, author at The Wall Street Journal, once asked: “HFT faces widespread criticism—what exactly did they do wrong?” As founder of Tabb Group, he supports HFT, arguing it makes markets “more efficient than ever,” enabling institutions to complete trades in milliseconds—an achievement of technological progress.

The essence of HFT is saving time and accelerating trade execution—all ultimately aimed at earning money more efficiently.

Yet critics like Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban call HFT the “ultimate hack,” arguing its speed games have nothing to do with real company value. Buffett has also mocked investment strategies relying on complex formulas. In 2005, he made a $1 million bet that hedge fund returns couldn’t beat index funds. In 2007, Ted Seides of Protege Partners accepted the challenge. Ten years later, Buffett’s chosen index fund achieved an average annual return of 7.1%, compared to just 2.2% for the five hedge funds—more than triple the return.

HFT firm returns are also declining. According to Institutional Investor in 2016, only Renaissance and Bridgewater managers earned over $1 billion annually, yet their performance has lagged the broader market for several consecutive years. Today, with more HFT firms and a fairer market, individual participants earn less than before. Still, the trend of machines replacing humans is irreversible. In March this year, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager (with $5.1 trillion in assets), began using AI for stock selection and laid off over 30 analysts and fund managers—about 7% of the department.

Lessons from High-Frequency Factors: From Microseconds to Daily Life

Though HFT may seem distant, its principles can be applied to personal investing. Converting high-frequency data into daily data can still uncover solid alpha returns. The relentless pursuit of speed is not just a technological arms race—it’s a reflection of rising efficiency in financial markets.

In the race between machines and speed, no one can afford to stop. The future will bring more surprises and challenges in fintech—are you ready?

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News